Reflections of a Maltese Muslim on belonging, ‘halfies’ and ‘oxymoron’ identities.

by Ibtisam Sadegh

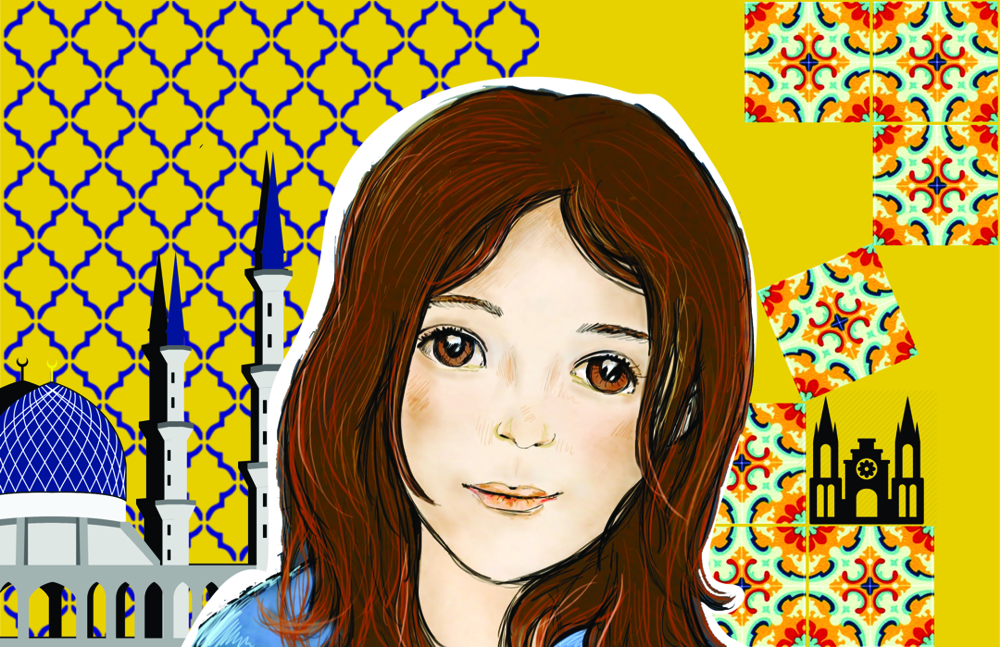

Collage by the IotL Magazine

‘Ikliniza’

I grew up in Iklin; playing passju and noli with neighbours back in the 90s, when children were at liberty to play safely in the villages’ side streets. Some of my fondest childhood memories include my parents taking me to village activities. Every lejla sajfija, flower and clean-up Iklin event, we were there. My parents had purchased a small patch of land in the Lija suburb of Iklin in the mid-80s, when the neighbourhood was merely a rural area. They constructed the very first few streets and built up a terraced house that my two brothers and I would eventually call ‘home’.

So, ‘Ikliniza’ is my reply to any Maltese who asks ‘where are you from?’

Around my early teens I realised I was, bizarrely, the oldest Ikliniza I knew. All my friends residing in the village oddly identified with the neighbouring villages. I learnt that we Maltese tend to identify with the parish where our christening is celebrated. But before the parish of Iklin was formed, Sunday mass was hosted in a small garage just a few streets away from my home and so residents baptised their newborns in adjacent villages, and they accordingly identified as coming from there.

I was never baptized. Since my childhood memories and roots are deeply founded in Iklin, I never once doubted Iklin as my village, home and regional identity. Even now, despite having left my parents’ nest, Iklin is where I am from.

‘I am Maltese, but…’

It took quite some time before I (accidentally) learned that within the village, my family was known as—‘tal-Libjan,’ —of the Libyan. The descriptive term forthrightly referenced to all members of the family by my father’s nationality.

In the 70s, my mother—from Birkirkara—joined Libyan Arab Airlines based in Tripoli, Libya, as an air hostess. She met my dad through some mutual Maltese friends. Their interfaith relationship withstood the distance, time and existing hurdles and a decade after their first meeting they celebrated a Muslim and civil marriage in Malta and proudly acquired land in Iklin, where they agreed to live and raise their children, as Muslim.

This meant that my brothers were both circumcised, my parents never cooked pork and alcohol—even cigarettes for that matter—was in principle prohibited at home. It meant that in Ramadan, we fasted from sunrise to sunset, while at Christmas and Easter we ate like there was no tomorrow at organised family dinners. We celebrated and grieved besides our Christian family and friends in church weddings and funerals. And we travelled to Libya during summer school recess to visit our Libyan relatives and participate in their festivities.

We celebrated and grieved besides our Christian family and friends in church weddings and funerals. And we travelled to Libya during summer school recess to visit our Libyan relatives and participate in their festivities.

Identifying as ‘Muslim’ also meant that we were exempted from sitting for ‘Religion’ exams in school; I nevertheless always participated in class, eagerly learned about Christianity and joined my classmates in the occasional school masses. And on Saturday afternoons, we regularly went to the mosque to learn about Islam and socialise with other Maltese Muslims.

Despite my mothers’ conversion to Islam prior to marriage, my parents cultivated a discourse of shared values and monotheistic affinity. My brothers and I were taught that there are more similarities than differences between Islam and Christianity, that there is only one God and that it’s the same God, in both religions.

![]()

‘I am Maltese,’ I assert to those who cynically question or glare the instant I pronounce my Arabic name or refuse to drink an alcoholic beverage. ‘But, my father is Libyan and my mother is Maltese,’ I add, when the sceptical or the curious refuse my answers, take guesses at my roots or demand further clarification. The response to this reply could range from polite silence and acceptance, to the friendly ‘I have a Libyan/Muslim friend,’ or the most certainly absurd, ‘I can see it in your eyes!’

Unlike my father or Muslim women with hijab, at first sight I “pass” as the ideal Maltese candidate; until, of course, I reveal my Arabic name when introducing myself in person or in written correspondence in English (where I sign off with my name without the possibility to further elucidate and fight my case).

I grew up seeing my migrant father being bluntly discriminated against, treated as if he were an outsider and a parasite siphoning on Maltese society and this despite his having lived here for over three decades, his fluency in the Maltese language (although with an obvious Arabic accent), Maltese citizenship, wife and kids. Perhaps consequent to my parents’ recognition that my father will always be treated as a ‘guest’ who should be utterly servile and grateful to the fellow Maltese for mere tolerance of his presence, my siblings and I were raised with the principle of publicly avoiding any discussions involving politics or religion, fearing prejudice in our regard. We were continually told to act with kindness, get a solid education, ignore unwarranted remarks and always avoid trouble or political and religious activism.

I grew up seeing my migrant father being bluntly discriminated against, treated as if he were an outsider and a parasite siphoning on Maltese society and this despite his having lived here for over three decades, his fluency in the Maltese language (although with an obvious Arabic accent), Maltese citizenship, wife and kids.

I thus learned from a young age the necessity to continuously navigate my Muslim background, maneuver my identity and emphasize my Maltese-ness. Such daily strategies include me explaining the meaning behind my given name; at times even de-Arabizing it by abbreviating it to ‘Ibti’ or writing inquiring emails in formal Maltese—all in attempt to be recognized and treated as equally Maltese.

The coming-out as a ‘halfie’ Maltese at every new encounter and the shocked reactions towards my seeming ‘oxymoron’ identity of a Maltese Muslim (yep, not all Maltese are Roman Catholics!) is tedious, tiresome and annoyingly repetitive at its best. When my strategies fail to impress, the response and impact varies from undermining me as a lower category of Maltese—half-westerner, half-barbaric—to different treatment and possibly, raw undisguised bigotry on nightmarish occasions.

Being Muslim and Maltese… in Ceuta

Across the straits of Gibraltar on the North African Mediterranean coast, where I spent 14 months conducting ethnographic research, questions such as ‘who am I?’, ‘what religion am I?’ and ‘what are my roots?’ were part of my daily interactions with Ceutans, Moroccans and other residents of the Spanish enclave of Ceuta.

‘I am Muslim and Maltese,’ I would answer to their questions… no buts included!

Ironically once outside of the Maltese shores, my ethno-religious background was no longer a handicap and my Maltese Muslim identity was acknowledged to the full, even appreciated, as my social circles of Muslims and Christians continually grew.

Ceuta is a zone of intense confrontation yet also of peaceful quotidian coexistence between Christians, Muslims and smaller numbers of Hindus and Jews. The Ceutan government, perhaps in response to the dense heterogeneous population, extolls a discourse of ‘convivencia’ which promotes and celebrates the diverse local ethno-religious groups living peacefully together as well as their mixing. The political discourse of convivencia, today permeates Ceuta’s political, economic and social life and is even used as shorthand to describe the local environment. It is mobilized by Ceutans to bridge ethno-religious differences through the overarching, regional (as Ceutans) and national (as Spanish), identity.

Despite clear limitations to the concept and the obvious socio-economic and spatial divides between ethno-religious communities in Ceuta, this discourse and ideal of convivencia has left a personal impression on me as it creates a unique space for public debate on national and religious identity, and facilitates a clear distinction between the two; starkly contrasting with the local situation that defines national identity almost exclusively along religious lines.

Being Muslim and Maltese … in Malta

Those who, like me, do not easily fit into the rigid rhetoric of ‘Malta is a Roman Catholic Country’ challenge the dominant understanding of the ‘Maltese’ by their mere existence.

Hostile slurs such as ‘if you don’t like it, go back to your country’ allow (and deserve) no further debate; and of course, they beg the sarcastic question ‘to where?’ when addressed to people like me.

I feel it is long due to acknowledge that the Maltese constitution, proclaiming that Malta is a Roman Catholic country, must be amended to reflect the fresh, existing diversity of religions and cultural identities.

I feel it is long due to acknowledge that the Maltese constitution, proclaiming that Malta is a Roman Catholic country, must be amended to reflect the fresh, existing diversity of religions and cultural identities. Maltese identity stems from—and is continually reinvented by—a mixture of ethno-religious backgrounds. As of yesterday, we should take pride in all Maltese history, rather than distancing ourselves from our Islamic and Arab heritage in a desperate attempt to prove our Europeaness. In no way does one contradict the other; likewise Maltese identity does not exclude other backgrounds.

Let’s learn from Ceutans’ discourse of convivencia and allow a healthy discussion on religious and national identity. Let’s appreciate our similarities and differences:

‘I am Maltese, and European, and Muslim, and… more.’ No buts, only ands!

Ibtisam Sadegh is a PhD researcher in the ERC project hosted at the University of Amsterdam and is currently writing an ethnographic dissertation on interfaith couples in Ceuta. She previously read law at the University of Malta.

Leave a Reply