“There are artists who are more into playing with the rules of art and artists who would rather play with the rules of society and the legal regulations. To me, the real art is the latter—the art that exists between creativity and criminality (not because it’s ‘criminal’, but because it challenges unjust legal practices).”

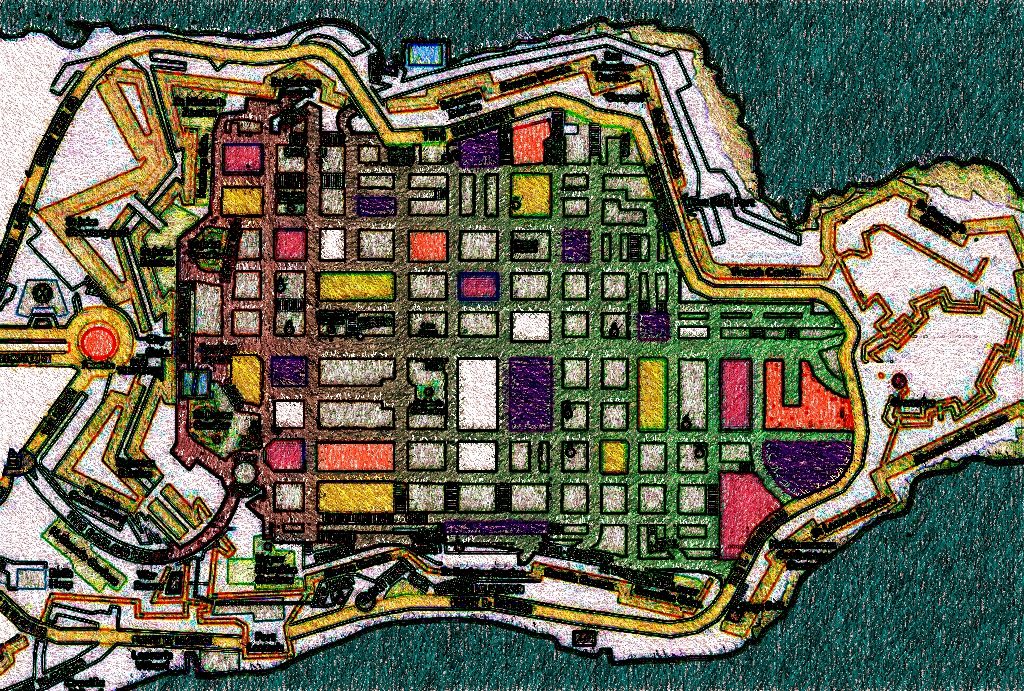

Image by Isles of the Left

Raisa Galea spoke with Pascal Gielen, Professor of Culture & Politics Sociology at the Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts, about the role of art and artists in reclaiming the contemporary cities from the commercial players. Prof. Gielen will be giving a talk at the Valletta 2018 Annual Conference on the 25th of October.

Raisa Galea: Your contribution is titled “Art, Politics and Public Life in the City of the 21st Century”. In what way do today’s relations between urban art and politics differ from those 50 years ago?

Pascal Gielen: Since the 19th century and until today, there have been four major shifts in the relations between politics, art and public life in the city. In the 19th century and until the end of the 1950s, arts in the cities were performed in a traditional ‘bourgeois’ way and were limited to fixed spaces, appointed for this purpose. For instance, statues were placed in specifically designated spots; performances happened in national monumental theatres. Arts were administered by national governments. That’s why I call urban culture with this kind of relationship the ‘Monumental’ city. Such a relation between art and politics was contested at the end of the 1950s with a symbolic culmination point in 1968.

The Paris protests of May 1968 provoked a monumental change. The demonstrations, reaching the highest point in the students’ protests, challenged the hierarchies—that, I believe, was the first significant shift from the traditional system of the 19th century. I refer to this shift in urban culture relations as the ‘Situationist’ city because the protests were inspired by the Situationists, who called for dismantling the rigid urban structure administered by highly hierarchical (cultural) institutions.

The second shift happened in the 1980s, when the students of the 1968 became in charge of the cities and the real estate. The protesters of the 1960s converted into the new management in the 1980s. At that point, cities were in permanent transformation, always under construction. And this was the time when politicians came up with an idea of city as a space for creative industries.

Once the politicians let the money flow freely around the globe, countries and cities had to find ways to attract new investment to compensate for the collapsed manufacturing of the industrial period.

Creative industry politics was born at the moment Tony Blair embraced Bono of U2. Third Way politicians, as we know, had a soft spot for the markets. Saskia Sassen, in her book “The Global City”, describes how cities turned into financial centres, the focal points of the global economy. Once the politicians let the money flow freely around the globe, countries and cities had to find ways to attract new investment to compensate for the collapsed manufacturing of the industrial period. And, as a marketing strategy, governments and local politicians came up with a plan of promoting creative industries. ‘Creative cities’ were meant to attract tourists. These ideas were also actively advertised by Richard Florida in his influential books “The Rise of the Creative Class” and, especially, “Who’s Your City?”.

The puzzling phenomena about the places reborn as ‘creative cities’ is that prior to the shift towards neoliberalism they were governed predominantly by socialists. A few years later—this is the third major shift—in a lot of cities the socialist and Third Way mayors were replaced by right wing conservatives and neonationalists, who adopted the idea of the ‘creative city’ for economic reasons, yet, at the same time, brought forward the ideology of, what I call, ‘repressive liberalism’ and even zero tolerance. This shift led to a higher police presence and a more intensive automated street surveillance. Such cities have a paradoxical relationship between art, public life and politics, which is why I call them ‘Creative-repressive’ cities. This is where we are at the moment.

The way creativity is defined, and in which places it is allowed to happen, determines society.

The way creativity is defined, and in which places it is allowed to happen, determines society. When creative activities are reserved for ‘creative’ fashionable districts (for instance, Vienna’s Museum District), then, inevitably, such spaces become restrictive. So, paradoxically, the artist can be free to create, but only in the creative district with its strict economic conditions.

I do not know what the future will bring. However, I do hope that the ‘Creative-repressive’ city will give way to the ‘Common city’, where social class distinctions will not be prominent and where creative communities—together with other people—will reclaim parts of the city from commercial interests.

Applying this classification of relations between politics and art to Valletta, I would say we are still at the stage two, where development of creative industries serves as a marketing strategy for the sake of attracting investment. The preparations to and the arrival of the European Capital of Culture 2018 have revamped Valletta—it is no longer a city of dilapidated buildings and an absent nightlife. There is, however, a concern that the city will end up as a theme park for entertaining tourists. What can be done at this stage to preserve spaces for public life in the city?

At this point, it is essential for the people of Valletta to keep control, collectively, over the key infrastructure, including culture infrastructure such as theatres, museums, and public spaces. By that I mean having a say on the programme of these theatres. The focus needs to be on reclaiming the city from AirBnB and other large real estate companies which extract profit from it. They milk the city dry, so to speak. These companies replace the use value of the city by a speculative exchange value, which is a disaster for the urban cultural and public life in the long run.

The real estate companies milk the city dry. They replace the use value of the city by a speculative exchange value, which is a disaster for the urban cultural and public life in the long run.

In theory, that would be an ideal scenario. However, Valletta is a city of contrasts and, in practical terms, that means deep segregation along the social class and partisan lines. The affluent residents of Valletta are predominantly in favour of boutique accommodations and AirBnBs, since that means more profit. The underprivileged population of Valletta lives in state-subsidised properties and is unlikely to march against AirBnB and commercialisation of space.

Unfortunately, Valletta is no exception. I see this happening in many other cities. To a large extent, this is a fault of the EU policies which stimulate competition between cities, incentivising them to develop unique features, but the cities end up copying each other in a bid to attract more tourists.

The situation in Leeuwarden—a Co-Capital of Culture 2018—is not too different. Having said that, from the beginning of the ECoC project, there have been active public discussions urging to invest into local co-operatives and green festivals that involve local farmers. Local people of Leeuwarden, too, had a say on which sectors should be invested into. We still need to evaluate whether these intentions have succeeded under a pressure from the international rat race between cities, stimulated by EU policy.

With the current trajectory, Valletta will experience four-five more years of economic growth (with a severe gentrification process parallel to that), followed by collapse.

Going back to Valletta: with the current trajectory, there will be four-five more years of economic growth (with a severe gentrification process parallel to that), followed by collapse. In most cases, cities cannot keep attracting tourists indefinitely. Take Bilbao, for instance. There was a boom—a revival through the creative industries. In a few years’ time, the majority of avid travellers have seen the iconic buildings, the interest in the city dropped—and the boom was over. In such circumstances, cities have to come up with new spectacular projects—architectural and entertainment—for the sake of luring the tourists.

Which means that cities begin to function for a purpose of entertaining tourists…

And it also means that the same economic bubble is happening—albeit propelled by creative industries. In 5-10 years it will be over.

On a more optimistic note, how would cities that are currently at the ‘revival through creativity’ phase (or are at the ‘creative-repressive’ phase already) transform into common cities?

It is no historic fact, but an assumption. When collapse follows revival, cities fall into crisis, and in order to emerge again, they have to reinvent themselves—this is where the possibility for the positive change lies. The city of the future could be a Common city.

The movement for the Common city is driven by a heterogeneous group of people who are united by the common interest—reclaiming the city from the commercial, gentrifying forces.

Some shifts are already happening. The movement for the Common city is driven by a heterogeneous group of people, who, despite the professional and lifestyle differences, are exploited in the same way and thus become united by the common interest—reclaiming the city from the commercial, gentrifying forces. This struggle brings together activists, youth, social workers, factory workers, feminist and queer groups. Certainly, creative workers are drawn in too. In Zagreb, for instance, music bands and DJs, who squat places for the parties, join protests against large shopping malls and big companies moving into the district. These groups have a great potential; their protests are playful and provocative.

Other movements for the Common city are led by collectives like Recetas Urbanas—a Spanish architect collective whose members build houses and schools; who ask people what they would like to have built. Sometimes their creations are illegal or ’a-legal’, installed in spaces outside of legal regulations. In Sevilla, Recetas Urbanas created an insect-like structure, attached to the tree trunk, which also serves as a provisional shelter. As is in other cities, homelessness in Sevilla is on the rise, with homeless people being barred from public spaces. Tree trunks, where the provisional shelter by Recetas Urbanas is located, are not regulated by law, meaning that police do not have the legal means to evict a person from there.

The collective chooses such a-legal spaces for their intervention on purpose—to begin reclaiming the city for all, to open spaces up again and to attract attention to the problem. And not only that—they also built schools where people needed them and they continue assisting the local communities in a struggle to safeguarded cultural infrastructures from real estate speculation.

To me, the real art exists between creativity and criminality (not because it’s ‘criminal’, but because it challenges unjust legal practices).

This is a completely different, radical way of doing art. The art for the Common city is art motivated by civil concerns. I do not call commodities designed for rich people ‘art’ anymore. That includes festivals, art displays and biennales—they exist within the art market and have their own distinctions, thus they are commodities nevertheless. There are artists who are more into playing with the rules of art and artists who would rather play with the rules of society and the legal regulations. To me, the real art is the latter—the art that exists between creativity and criminality (not because it’s ‘criminal’, but because it challenges unjust legal practices).

Somebody might say this is “instrumentalizing art for social causes”…

Yes, quite a few people say that and I disagree. These radical art collectives are autonomous in many more ways than artists creating for the market, for art festivals or biennales. Rather than adjusting to the demand of the market or the competitive professional art system, the collectives rely on public support, which allows them to focus on a broader variety of topics. Not all works of Recetas Urbanas are admired. Sometimes the public does not like their work, but the interventions are provocative enough to encourage further questioning.

The autonomy of Recetas Urbanas is fascinating. They get no support from the government (which government would support artists creating in a-legal spaces?), neither do they have private sponsors because the latter would not like to be associated with their explicit political actions. Yet, they have been going strong since 2003.

Not only do the radical art collectives operate within a democratic setting, but they also lay a foundation for the Common city’s infrastructure and the alternative economy.

And, naturally, the question is “where do they get the money?”. They collectively raise funds. They are skilled to reuse existing, discarded materials in new ways. They’ve built an extensive network all over Europe with whom they share the ideas and experiences. And they do it for free—peer to peer. Moreover, the works of Recetas Urbanas set a precedent: they inspire similar interventions in other places. Not only do the radical art collectives operate within a democratic setting, but they also lay a foundation for the Common city’s infrastructure and the alternative economy.

How is this kind of radical, socially motivated art different from community art?

In fact, it is quite different. Community art is driven by the notion of identity, it plays by conservative rules and is encouraged by conservative, nationalistic governments. It seeks to define “us” versus the other and, thus, exclusive. As described in our book ‘Community Art’, community artists are exploited by neoliberals and conservatives to compensate for the fruits of their policies—the disintegrating welfare state—by encouraging a particular kind of social cohesion, thriving on the ‘we’ feeling.

Unfortunately, I cannot think of any art collective similar to Recetas Urbanas in Malta at the moment. How can a society nurture such movements?

Certainly, you cannot tell artists to become activists or politically engaged. Such shifts happen when artists can no longer stay away from the consequences of the social, economic and political crisis. When cities turn into private commercial spaces that push people out, artists themselves become affected by it. They feel the urge to reinvent themselves and to organise their activity differently. And artists can inspire the radical change because they have a skill to make things visible.

Pascal Gielen is one of the keynote speakers at the Valletta 2018 annual international conference, Sharing the Legacy, taking place between the 24th and 26th October 2018. For more information, visit the conference’s website.

Leave a Reply