When information is fragmented and is constantly perverted to advance vested interests, it is only reasonable to doubt its accuracy. And when matters of justice are treated as mere pawns in partisan power games, democracy is indeed in danger.

by Raisa Galea

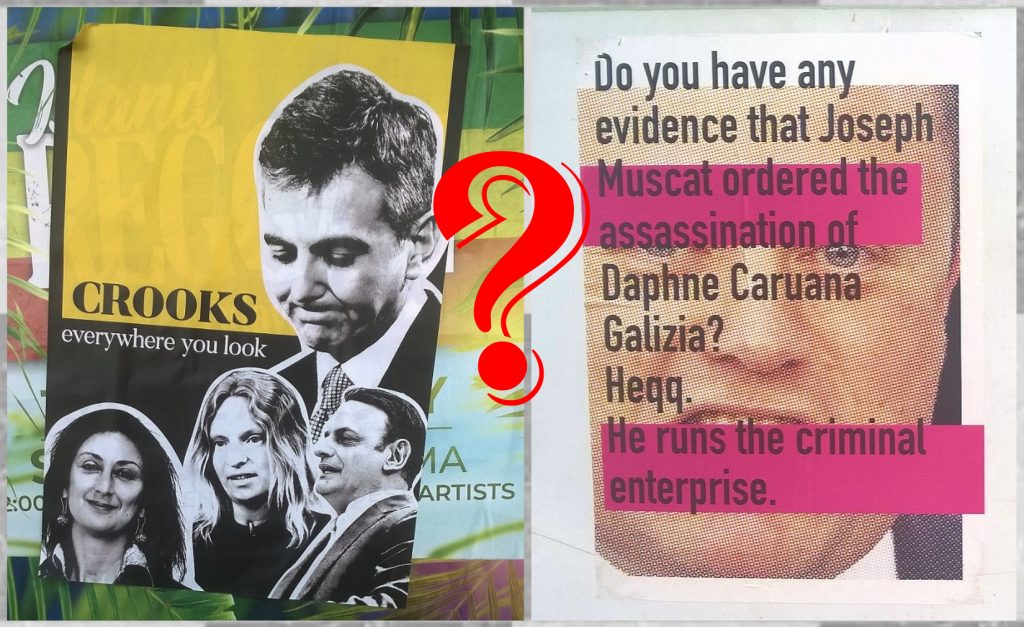

Collage by Isles of the Left*

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]y now, the Egrant scandal has become a tired affair, an echo of a past thunderstorm, fierce but done with. The inquiry was concluded on 21st July, and although it still is the highlight of partisan squabbles, it no longer features in heated public debates. Now is the chance to examine the matter and its consequences calmly.

How did we end up here? What does the scandal say about Malta at the moment? What’s next?

The Red and Blue ‘Truths’

It’s tempting to begin reflecting on the Egrant saga with a quote—overused and attributed to a great multitude of authors—“truth is the first casualty of war”. Although a cliché, it captures the state of affairs pretty well: when information is fragmented and is constantly perverted to advance vested interests, it is only reasonable to doubt its accuracy.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]When information is fragmented and is constantly perverted to advance vested interests, it is only reasonable to doubt its accuracy.[/beautifulquote]

Since the moment it thundered on the Maltese and international public on 20th April 2017, “Egrant” has been mentioned alongside “truth” in the official and social media so often that the two have practically become synonyms. It was even suggested that the allegations pointing at Michelle Muscat as a beneficiary of a Panama-based company must be true since they pass “the Occam’s Razor test: the simplest explanation is usually the right one.” Not only did such arguments conveniently ignore that Occam’s Razor is only applicable to specific questions of science and philosophy—not politics—but they also aimed at presenting assumptions as objective and science-backed facts.

To an unbiased observer with no partisan allegiances (yes, they exist), none of the material released so far might seem credible. Here is an official ‘truth’, as concluded by the inquiry: a signature on a declaration of trust showing Prime Minister’s wife as the UBO of Egrant—the major piece of evidence—was falsified. It also turned out that neither late Daphne Caruana Galizia, nor her whistleblower Maria Efimova, were in possession of the document (despite the claim of the former that the documents, supposedly obtained from Pilatus Bank’s kitchen safe, were “scanned and uploaded to the cloud”). Their testimonies, the inquiry decided, were “incompatible with each other, or completely disavowed by evidence gathered”.

The rival side, led by the Caruana Galizia family, Manuel Delia and the media portal The Shift, are not giving up their claims. They point out that “the scope of the inquiry was actually very limited”, that the denial of Jacqueline Alexander about the authenticity of her signature on the Egrant certificate is not to be trusted, that the Office of Prime Minister and the Attorney General are controlling what gets released and, finally, that “there are hundreds of gigabytes of evidence on Egrant“.

Do these counter arguments make sense? Yes, they do—at least some of them.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]It does seem perfectly sensible to doubt the testimony of a Mossack Fonseca’s employee, given the nature of their business.[/beautifulquote]

I am not equipped to assess legal matters, but still, it does seem perfectly sensible to doubt the testimony of a Mossack Fonseca’s employee, given the nature of their business. The fact that the inquiry has absolved the wife of the ruling prime minister, in the system which does not allow police investigations against the government without its consent, certainly leaves a room for distrust.

Matthew Caruana Galizia’s statement on “hundreds of gigabytes of evidence on Egrant” is also one to consider. As part of ICIJ, he analysed the documents leaked from Mossack Fonseca and must have gained an insight into the nitty-gritty of the law firm’s ways and means. Besides, the Caruana Galizia family enjoyed a direct proximity to power for decades, acquired an extensive network of connections and, hence, might have an access to unique sources of information.

There is a need for an additional remark though: all of these counter arguments would have been more credible, had they been uttered by individuals with no links to the PN and with no intention to advance the interests of their own clique by undermining the adversary. And this is indeed not the case.

Ultimately, the Egrant blockbuster has never been about fighting corruption, nor seeking justice. The battle broke over Egrant and not, for instance, the deals between Erdoğan’s family and Azeri state oil company assisted by Malta’s offshore tax scheme, because Egrant was the opposition’s chance to wrestle back control over the country. The other deal, although of comparable scale, did not advance the opposition’s cause: It would have only highlighted the troubles of Malta’s own apprentice and assistant of Panama—the financial services industry—the sacred cow which not even the most avowed anti-corruption crusaders dare to denounce.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Alas! Misappropriation of public funds and abuse of power are considered worthy of rallying against only when they favour partisan agendas.[/beautifulquote]

Alas! Misappropriation of public funds and abuse of power are considered worthy of rallying against only when they favour partisan agendas. When calls for transparency come from the opposition that is no stranger to corruption, it’s no surprise that the public receives them with scepticism. Besides, politicians who share the same EP party with Victor Orban’s Fidesz and who seldom raise concerns about the state of democracy in Hungary, cannot boast objective pro-democracy credentials either.

Leaving aside skepticism about the results of the inquiry, what can we be certain about?

First, the allegations were made without hard evidence to back them up—and this was done in a desperate attempt to get the then Busuttil-led PN back to power. Second, the owner of Egrant still remains unknown and is likely to stay that way, since the governing party will not call for another investigation, while the opposition, torn by internal conflicts, is licking its wounds. Third, the conclusion of the inquiry has given Keith Schembri and Konrad Mizzi—both of whom should have resigned long ago—a remarkable opportunity to gloss over their Panama companies and to whitewash Mizzi’s involvement in the inglorious Electrogas deal. Sad certainties indeed.

Read more: ‘Two Years Later: Panama Papers In Malta And Beyond‘

Daphne Caruana Galizia’s Assassination as a Testimony of Egrant

David Thake was not alone to declare that the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia itself proves her allegations true. This reasoning implies that the allegations were extremely threatening to the players mentioned—the Muscat family, the Alyev family and Pilatus Bank.

Did the Egrant scandal truly endanger Joseph Muscat’s status though? How much harm have the mentions in Panama Papers done to other politicians? Unfortunately, not as much as they should have.

The exposure of David Cameron as a beneficiary of his father’s Panama offshore trust did not put an end to his political career. Neither did Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, ex-prime minister of Iceland, lose access to power: although forced to step aside in the wake of Panama Papers, he later formed a new party and was re-elected to parliament.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]In Malta, the impact of Panama Papers was rather weak.[/beautifulquote]

In Malta, the impact of Panama Papers was rather weak. Corruption scandals failed to spark a mass outrage that would have challenged the government’s authority. Unlike the protests in Iceland, which mobilised more than 10,000 people to demand the prime minister’s resignation, the Maltese sporadic protests did not attract large enough crowds from across the partisan spectrum.

Egrant was no exception. The only notable outrage that followed the allegations was that of the opposition, once they learned about the election results: the Labour Party won by a spectacular 35,280 votes, right amid the accusations. Furthermore, Caruana Galizia was even mentioned as one of the reasons behind PL’s triumph. “Malta’s post-election wedding halls”, Ranier Fsadni wrote with contempt, “were full of people muttering that the Nationalist Party should ‘dissociate’ itself from Daphne Caruana Galizia”.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The danger posed by Caruana Galizia’s pen to the Maltese government is greatly exaggerated.[/beautifulquote]

The danger posed by the journalist’s pen to the Maltese government is greatly exaggerated. And yet, Daphne Caruana Galizia lies dead. Indeed, her revelations must have damaged the interests of the powerful. But whose interests were they? Were they of any supposed Egrant player? Or, perhaps, the interests of some beneficiary of Malta’s other offshore structures? We simply do not know yet. The ongoing investigations of the murder must establish that. And the responsibility of the government is to ensure that the results of the investigations leave no room for doubt.

How Did We End Up Here? What’s Next?

On their own, revelations are not enough to challenge abuses of power. Investigations like Panama Papers are meant to attract public attention to the world of wealth management, tax avoidance and crime. It’s then up to the public to hold the authorities accountable.

The reports of income inequality and injustice should be threatening. They should provoke mass outrage and instigate calls for justice. The public should be up in arms against offshore companies of state officials and murky privatisation deals. And the officials—not the public!—should resign.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The potential of corruption revelations to wake a democratic yearning from slumber is incompatible with a bi-partisan political system.[/beautifulquote]

Alas, the potential of such revelations to wake a democratic yearning from slumber is incompatible with a bi-partisan political system. The hundred thousand Romanians protesting removal of checks on affiliations between the authorities and obscure private interests contrast sharply with a wide-spread complacency about high-profile corruption in Malta. This contrast is inescapable and alarming. [*]

But how can an independent democratic mobilisation ever take off, when the public looks at constructive criticism of the authorities through the red/blue specs? How can it be different, if sprouts of any independent movement are devoured by the competing cliques in power? Besides, why should the principled public be forced to choose between the faction that acts like a possessive ex-lover with an outsize sense of entitlement and the government that brands its critics as ‘traitors’?

When matters of transparency and justice are treated as mere pawns in partisan power games, democracy is indeed in danger.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Only a break from the two-party system can create a space for independent trustworthy resistance to abuses of power.[/beautifulquote]

I leave it to lawyers to suggest improvements in Malta’s judicial system. From a non-partisan, socially concerned general public perspective, only a break from the two-party system can create a space for independent trustworthy resistance to abuses of power. The electoral system must enable other parties and independent candidates to represent the electorate in parliament (although there is currently the 3rd party in parliament, Partit Demokratiku had to contest on the PN ticket).

Someone might say that such a change will favour the likes of Imperium Europa or MPM more than Alternattiva Demokratika. Those are sound concerns. And yet, unless the bi-partisanship is done with, the abuses of power will go unchecked, with or without the extreme right in parliament.

It’s entirely up to us to hold the authorities accountable. No one else will.

Read more: ‘The True Power Of Your Vote‘

* The poster on the left declares “Crooks everywhere you look” next to the portraits of the former PN leader Simon Busuttil, Daphne Caruana Galizia, Egrant whistleblower Maria Efimova and PN MEP David Casa. Such a design hits a new low: a dead journalist cannot be seen “everywhere you look” since she is no longer among the living. The design palette—black, yellow and white—possibly alludes to the brand colours of The Shift.

[*] Correction as of September 6, 2018: It has come to my attention that the anti-corruption protests in Romania are not as non-partisan as was stated in the article. In fact, the situation in Romania is comparable to that in Malta, and is equally complex.

Leave a Reply