“There is nobody willing to listen to people like me. Nobody represents our interests anymore. The Labour Party has vanished.”

Raisa Galea asked Emmanuel Psaila, former Marine Estimator at Malta Drydocks, to share his perspective on migration and workers’ rights.

Image: Emmanuel Psaila (left) with MDD apprentices in 1976.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] was born in Cospicua, just 500 metres away from where Dominic Mintoff was born and lived in his younger days. Many of the Drydocks and port workers used to live there due to the vicinity of the port.

In 1975, I started working at the Drydocks. Previously at the Secondary Technical School, I learned the trade of woodwork and metal work besides many other subjects, such as engineering drawing. During break time, some of us had the privilege of learning how to build wooden boats or canvas canoes whilst the metal work practice even taught us how to make many types of screws. In fact, a screw is one of the most difficult things you can produce on a lathe machine. The acquired skills and knowledge helped me a great deal. At the age of 16 I was able to start working literally right upon leaving school. The next day after my last GCE examination, I was at work.

In 1975, I started working at the Drydocks. Previously at the Secondary Technical School, I learned the trade of woodwork and metal work besides many other subjects, such as engineering drawing. During break time, some of us had the privilege of learning how to build wooden boats or canvas canoes whilst the metal work practice even taught us how to make many types of screws. In fact, a screw is one of the most difficult things you can produce on a lathe machine. The acquired skills and knowledge helped me a great deal. At the age of 16 I was able to start working literally right upon leaving school. The next day after my last GCE examination, I was at work.

I remember it was the time when the Labour Party was in government again after a long time in the opposition. It was a revolution! The wages started to grow, especially the wages of the workers—such a great difference from how things used to be before, when clerks, or “workers of the pen” as they were called, were paid more than trade workers. My wage increased to 7 Maltese pounds per week. It was the time when the Labour party had three persons from the Drydocks as Members of Parliament—it literally was a Labour Party!

The other party, the PN, represented the high class. They teamed up with the church and did their best to undermine the workers’ movement. They also considered Maltese as an inferior language (‘lingwa tal-kċina’) and some of them still hold that perception up to this day.

There was a lot of work at the Drydocks. There used to be no less than 15 ships at a time. We were about six thousand people working there. There were no foreigners at that time except a few specialists, maybe. All the work was done by the Maltese.

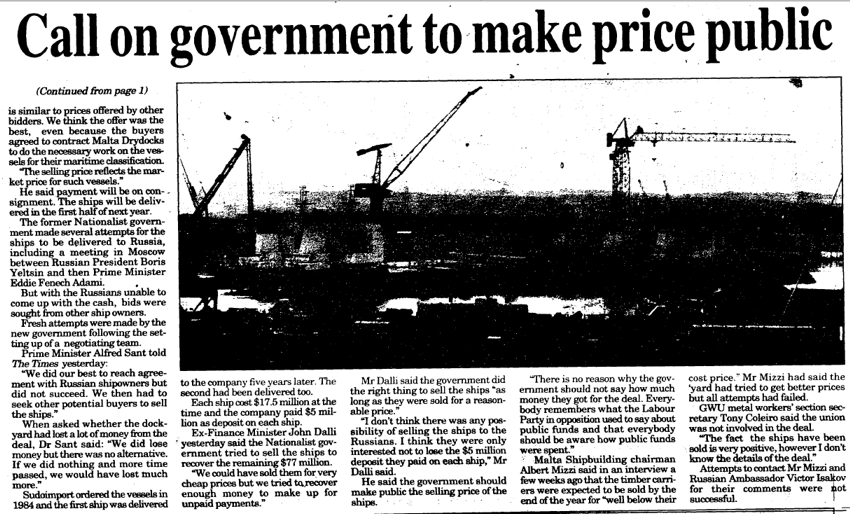

Everything worked quite well until about the year 1978. What happened then is that some Labour MPs started abusing the government: it began sliding into a kind of dictatorship. Most of the work came from the communist countries; the workers from Russia, China, Korea and Libya started coming over. But the situation became even worse when the USSR collapsed. In fact, we manufactured six ice breaker/timber carrier ships only to discover that they were to remain at the Drydocks since there was nobody to buy them! At the end, the ships were sold at a bargain price to Finland, if I am not mistaken. At the same time, some ship agents started bringing Polish workers with them. And that was the beginning of the end.

Clearly, the ship agents preferred bringing the foreigners because they had much lower wages than ours. The Drydocks started stagnating, going back further and further. The last 12 years I was there, from 1990 to 2002, I worked as a Marine Estimator. Our estimates were a hopeless case—the workload dropped so much that the Drydocks couldn’t cope.

In 2002 I retired from the Drydocks and started looking for temporary jobs. After having found a job at a renowned high-profile hotel, I discovered that the majority of other employees were foreigners. Though they all were hard-workers and decent people, their pay was quite low—and so was mine. At my previous job I was paid an equivalent of 1400 Euro and the job at the hotel paid 800 Euro.

The majority of the workers were from the Eastern European countries, mostly Bulgaria, who were willing to take as much work as they were ordered to. Apart from that, I have seen the history of the workers’ movement and knew how much we needed to fight for our rights! I thought that all our previous achievements were undermined by the foreigners willing to work more for less. Yes, they were hard-workers but I couldn’t say they always followed the quality procedures either. I could tell they were desperate: they agreed to work with no insurance and did not care for their own safety.

In fact, this is the main reason of my objection to the proliferation of migrant workers: we, the locals, are becoming unnecessary. I had to struggle a lot to acquire the job of a technician at MCAST.

The worst, however, is that there is nobody willing to listen to people like me. Nobody represents our interests anymore. The Labour Party has vanished. Joseph Muscat seems to know nothing about what happened during my time. To me, he is an aristocrat who cannot represent a party which calls itself “Labour”. Whenever I raise these concerns about the unfair competition which favours foreign workers over the Maltese, because they can be paid less, I am called a racist. I suspect that calling us racists is a legitimate excuse to humiliate and discriminate us, to give us a bad name. I beg to differ: the true racists are those for whom the workers, Maltese or from any other part of the world, are only numbers and tools of generating profit!

![]()

Isles of the Left selected this interview for publishing on the Workers’ Day intentionally. Unfortunately, in the aftermath of Brexit and the US presidential elections, the misconception which holds the working and lower classes responsible for spreading the seeds of racism and fascism due to their purported lack of cultural awareness and artistic education has been gaining strength. This prejudice is a convenient way to blame all misfortunes on the lower levels of social hierarchies, which is much easier than searching for the causes of the apparent nationalism and racism of the working class.

Emmanuel Psaila’s experience sheds light on the causes of anti-immigration stances of many Maltese workers: they often feel that the achievements of the workers’ movement of the 1970s have been undermined and reversed due to the migrant workers’ willingness to accept poor working conditions.

However, Emmanuel’s concern about “unfair competition which favours foreign workers over the Maltese” calls for a debate. Maltese and migrant workers face similar challenges, and, in many cases, foreign workers have fewer opportunities to defend their rights.

A few days ago Isles of the Left shared a story of an Italian female student who had to combine her full-time studies with part-time work at one of Malta’s best-known restaurants, where she was treated unfairly. Hardly can she be blamed for complacency with the mistreatment she experienced, since it was not her choice to end up exploited and underpaid. Thus, it should be clear that the true perpetrators are the employers and the pro-business policies favoured by Malta’s both major parties. The only possibility there is for workers—domestic and foreign—to defend their rights is to stand united.

I do not agree with your views at all. Immigration should be controlled especialy in a country like ours were resources are limited and opportunities scarse. Uncontrolled immigration serves only to undermine the negotiating position of those who only have their personal abilities to rely on.