It is not the ‘ugly and stupid’ art that needs to be smashed and never sent for repair, but the insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

by Raisa Galea

Picture by the author

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ust as it happens with most topics in Malta—from over-development to fast food adverts—the disputes about the quality and the place of art in the society quickly become absorbed by customary narratives: partisan rivalry and the country’s purported status of the ‘citadel of mediocrity’. Despite their dull uniformity, these disputes are worth looking into—they could suggest how Maltese people tend to relate to each other and to the outer world.

To begin with, public access to the arts in Malta is limited: Only a few places such as Spazju Kreattiv at St. James Cavalier, Malta Society of Arts and MUZA (a project still in the making, previously known as National Museum of Fine Arts) welcome the general public—that is, the majority whose professional and consumption interests are not directly linked to the arts. Other than that, contemporary artworks are displayed at art events, of which there are plenty. Most frequently, art is showcased at private exhibitions and book launches which, by default, imply their secluded or commercial nature.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences.[/beautifulquote]

Engaging with the art at social events cannot be contemplative and serene due to the confines placed by an informal code of conduct that the attendees are expected to uphold. The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences. That turns events-going into a hollow performance aimed to affirm the social status of attendees which has little, if at all, to do with the art.

Artistic experiences in Malta are also profoundly shaped by the country’s minuscule size.

In a small, densely populated country, a person usually meets artists before their works, unlike in the majority of larger states where pieces can be seen as anonymous and independent from their creators. The proximity to the artists is more likely to separate the general public from the art. It either results in a few fan clubs surrounding the artist or, on the contrary, the audience rejects the works straight away because they are repelled by the artist’s persona. Had Picasso lived and created in Malta, with his reportedly bad temper, he would have never gained any recognition for his works locally, in such proximity to the potential audience.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Nepotism, patronage of the governing elites, the lack of transparency in the process of allocation of public funds all create an ambiance of distrust which does not help promoting the arts.[/beautifulquote]

The partisan rivalry pervades practically every sphere of the Maltese society and the public perception of the arts is no exception. Nepotism, patronage of the governing elites, the lack of transparency in the process of allocation of public funds all create an ambiance of distrust which does not help promoting the arts. For instance, given that the Chairman of Valletta2018 Foundation and its Artistic Director are both Labour Party’s appointees, the V18 activities are bound to be trashed immediately, regardless of their quality, especially by the PN’s die-hard supporters. A fair critique of patronage is then brushed away as ‘elitist’ (and this excuse is accepted, mainly due to the prevalence of conservative takes on art in Malta).

Thus, the layers of individual, partisan and class biases are the obstacles between the artworks and the public.

In such circumstances, open air art displays could have been a remedy. Anonymous and open for everybody to contemplate on, they could bring art closer to the public and enrich our daily experiences. Instead, once introduced to the public space, the installations are instantly seized by the ‘taste police’ who asses their appropriateness to represent Malta’s creative potential. Worse, if the artworks do not meet the expectations of this informal ‘ministry for aesthetic standards’, they risk to be vandalized.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Denigrating another is the easiest way to assert one’s own virtue and that is exactly what the members of Malta’s ‘taste police’ live for.[/beautifulquote]

Whether it is due to its provincial status or the remnants of colonialism, the cultural scene in Malta seems to be in a perpetual reaction to the label of mediocrity placed on it by a number of Maltese. To the ‘aesthetic police’, there can be one and only ideal of ‘Culture’—that of a cathedral of supreme sophistication whose doors should be shut for ‘tasteless plebs’. Denigrating another is the easiest way to assert one’s own virtue and that is exactly what the members of Malta’s ‘taste police’ live for.

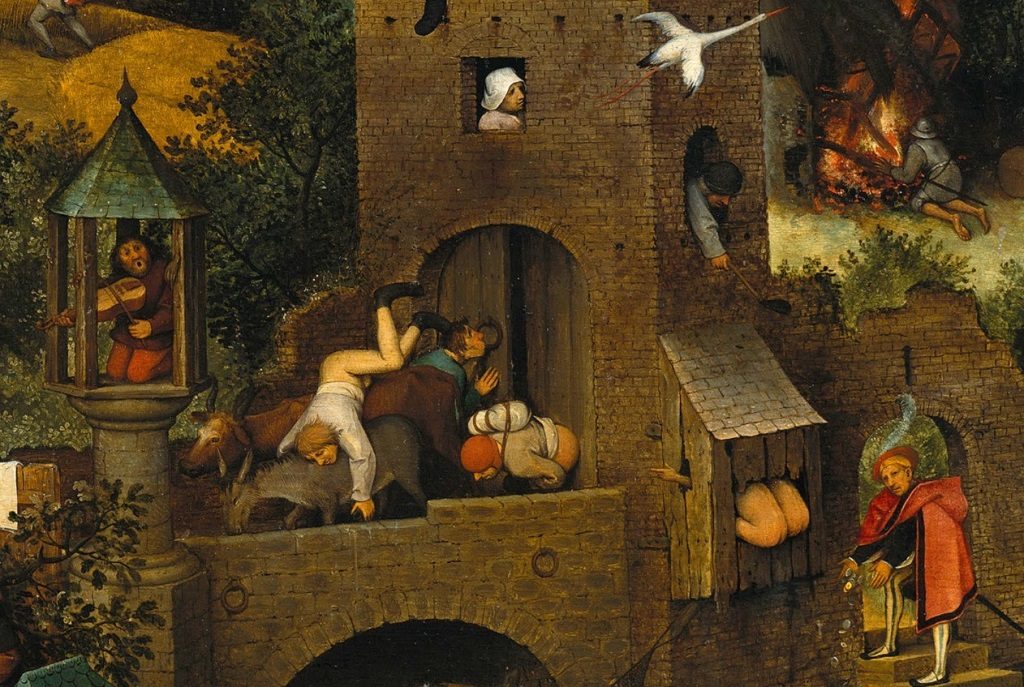

The eagerness of some individuals to stress their disdain for mediocrity reaches the level of absurd. I recall an opinion of a Maltese art enthusiast about Bruegel. Apparently, I learnt, the Flemish painter was a mediocre artist because his works were ‘cluttered’ and did not abide by the “less is more” dictum. Since not even Bruegel’s Dutch Proverbs seem to be up to the ‘standard’, the V18 Kif Jgħid il-Malti project which translated Maltese proverbs into art, was destined to insult the aesthetic sensitivity of ‘taste warriors’.

Habitually, the dispute focused entirely on the surface of the artworks. Their polystyrene medium was more worthy of a debate than their symbolic meaning. Hardly was it pointed out that the carnivalesque figures were well-timed to the Carnival—itself a feast of mockery and grotesque exaggeration. In my opinion, the project succeeded to achieve what it aimed for—the playful, quirky, cheeky and elementary outlines of these sculptures had brought the proverbs to life. The metaphors became tangible.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Those who ‘stick their nose between the onion skin’, who intrude into affairs of others, become tainted—and that is precisely what the sculpture conveyed.[/beautifulquote]

The sculpture of the man with the head stuck in the onion captured “bejn il-basla u qoxritha” perfectly well. Those who ‘stick their nose between the onion skin’, who intrude into affairs of others, become tainted—and that is precisely what the sculpture conveyed. It carved out the image of a gossiper. It ridiculed the intruder. It need not be more sophisticated because the proverb itself is coarse and direct. And, I believe, its honest primitivism surpassed the unimaginative critique that denounced it.

It seems plausible that the ‘folk crudeness’ of these sculptures alone was capable of provoking fury, leading to vandalism. It could be that the ‘taste warriors’ volunteered to swipe the European Co-Capital of Culture clean of ‘jablo junk’ a few hours after it had ‘contaminated’ Valletta. Bizarrely, the move was applauded by Mark Anthony Falzon, a prominent intellectual, who stated that “the vandalism of stupid ugly things in public spaces is not in the least distressing”. I hope that insecure conservatism that judges the art entirely by its surface appeal can also be considered ugly and stupid. That way it can be smashed and ditched straight away with no apologies offered.

When public art displays—sophisticated or crude—are scarce, having more of them is vital. Let them be ‘beautiful’, ‘ugly’, ‘noble’ and ‘profane’. Simply let them be.

Perhaps they succeed to stir curiosity and spark a few conversations. One day, these conversations will delve into symbolic meanings and wake the ephemeral beauty deep within each one of us. But first, the public needs to acquire safe access to the art; and the open air installations are fit for this mission best, because they create a space free from the partisan and social class confines. This democratic access to the arts, too, must be guarded from the dominant conservative perceptions that infinitely seek to segregate the ‘noble and beautiful’ from the ‘ugly and profane’. Valletta 2018 does not need more insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

![]()

The article borrowed an argument from the author’s earlier piece.

While I agree with your well articulated stance, I believe that part of the problem with the proverb sculptures was how they were marketed to the public by the institutions in question. Like you I did feel they were meant to be quirky, weird and not taken seriously but the way they were presented by the Foundation seemed to deliver the generic “look how great we are, look how great Malta is, these are masterpieces because we commissioned them” message instead of letting the public the decide how to engage with them. When the V18 chairman shared the video of the kids tempering with the sculpture and appealed to the police to ‘hunt’ for them, he was defeating the purpose of having such public art on display. The institutions have to understand that it does not hurt to have some sense of humour and poke fun at oneself…and these sculptures could have been a good opportunity to lessen the seriousness that usually surrounds institutionalised art in Malta, of which I think frankly, we need a break from sometimes. The ‘taste police’ would be left with little to say if there was already a more reflexive and self-aware approach when presenting the works, because it would be implied that their input and critique are part of the the outcomes expected and not taken as an offensive gesture.

Also the fact that the artist that was commissioned to make the sculptures has had a number of other previous Direct Orders from government initiatives (every budget campaign since 2013, the CHOGM campaign, the Planning Authority rebranding process to name a few) did not really help shut up the people who are quick to resort to the usual partisan rhetoric.

Thank you for your comment, Andrea.

I might be wrong, but it seems that what you describe as “look how great we are” is in itself a reaction to the usual “Malta is so backwards, mediocre, not a normal country” viewpoints.

The attempts at Maltese nationalism are a joke (and let them remain it) because they seek to prove Malta’s place within the ‘Great Western Civilisation’, not establish Malta’s virtue in its own right. Malta is a post-colonial country, after all. The nationalistic stances only seek to underline Malta’s ties to Europe, Christendom and the ‘proper civilisation’. Not even Norman Lowell believes Maltese are great enough, let alone the others.

Regarding the ‘taste police’. I’m not certain anything at all is good enough for the folks. I’m acquainted with some and had a fair share of sociliasing with them. All I can say is that communicating with this social bubble can discourage from attending art-related events. At least, that is what happened to me.

I share your disapproval for patronage, nepotism and the lack of transparency. It still is unnerving to be trapped in the usual, hysterical partisan debates. The partisan backlash deprives the public of artistic experiences. A grave deprivation, I believe.

P.S. This forum was set specifically for the purpose of hosting such exchanges. Anyone who subscribes to the principles of equality, social justice and sharing of resources is welcome to discuss and contribute, regardless of their social class and voting preference.