If refugees and migrants do not simply “become like us”, forgetful of a system which will keep producing its outcasts, the ‘vanguard’ of refugees may become the sign of a new beginning, of the possibility of a different world.

by Kathrin Schödel

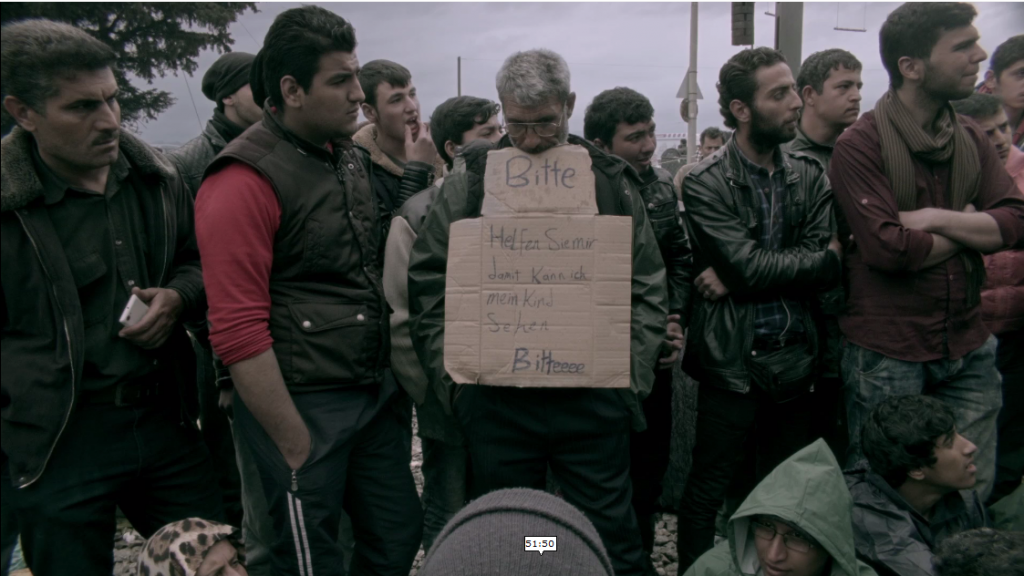

Image: “Spectres are haunting Europe” (France/Greece 2016, Maria Kourkouta/Niki Giannari), a still from the film.

“The Borders are Closed”—“Open the Border”

People moving slowly, queuing, waiting, somewhat out of place, something is not right: the clothes are dirty or too large or hardly fit for the weather; the weather is too bad for staying outside, but they are. Many are wearing the same raincoats—long with hoods, sometimes transparent, like a second ghostly skin—spectres in the rainy, muddy darkness of a camp.

The scenes were filmed in the refugee camp near the Greek village of Idomeni on the border to Macedonia in March 2016 when the European Commission had decided “to close the so-called West Balkans route” and “more than 15000 people found themselves stuck on the greek side of the greek-macedonian border”, as the closing titles of the film explain.

During the first part of the film, official, calm and functional loudspeaker announcements about the closed border and the provision of minimal aid by the Greek government asking for cooperation “with the Greek authorities” are juxtaposed with the chants of “open the border” by groups of refugees—one of the lines of the film which will haunt the viewer. The resistance to being put up in ‘reception centres’ in Greece and the decision of the refugees to stay near the border in the hope of being able to move on to the countries they intended to reach becomes a symbol of questioning the way in which human beings—not the ‘flow’ of anonymous masses, but the desires, decisions and plans of individuals—become pawns within the political manoeuvring between the different governments and institutions of Europe. Sadly, this is again a pressingly topical issue with people trying to cross the Mediterranean used as pawns in political disputes between and within European states—with deadly consequences.

Filming a Mass of Spectres?

The film’s recurring, haunting images are of lines of people navigating the muddy ground of an inhospitable landscape. But even when the images do not show faces, but focus on the feet or the backs of people, we see individuals, not an undifferentiated mass. The film does not employ the common strategy of narrating the stories of individuals amongst this mass, but it succeeds in portraying the mass itself in a different light: the problem is not the mass.

It is not by definition that a mass is dehumanising. The problem is the treatment of the mass. The creation of a mass by keeping people from exercising individual freedom. All too often, images of migration show a mass, a so-called ‘flood’ of people, ‘the migrants’, as if they were a homogenous whole, a mass of spectres threatening ‘us’—a mass in need of being controlled, even exorcised. The film manages to counteract these images by revealing a different mass, one which should haunt our conscience and our political will, not our fears.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]People’s reactions display many small and significant activities of life: washing clothes in spite of the rain and mud, preparing food with makeshift cookers, children playing, looking at the camera, people laughing and talking.[/beautifulquote]

The people in the film are not portrayed as passive victims; the difficulty of their situation is not hidden, but their reactions display many small and significant activities of life: washing clothes in spite of the rain and mud, preparing food with makeshift cookers, children playing, looking at the camera, people laughing and talking.

The camera is fixed; while people move and trains cross, the camera does not follow any of them, its angle remains static. This creates a tension between stasis and movement evocative of the many situations in which migration is actually standstill, waiting in spaces in between, being stuck where one does not want to be and did not choose to go. And the camera does not assume a privileged view-point so that its fragmented images are suggestive of the situation of unknowing and being subjected to the decisions of others, at the same time, it conveys the feeling of being part of the crowd, of the limited but direct view of a participant rather than of a distant or elevated observer.

Instead of the predominant representation of ‘the migrant’ as an almost inherently silent object—of administration and care but also of rejection and hatred—the ‘spectres’ of the film have voices: we hear them recite, joke, laugh together, forming a soundscape of humanity—and in the centre of the film discussing politics.

Memory: the Haunted Border

Those migrants who are constructed as a mass “haunting Europe” by media images are non-privileged migrants as opposed to those privileged migrants usually referred to as expats—not seen as a mass, not confined to a spectral existence, but openly dominant in the economy, politics and society together with their resident counterparts: the rich and powerful. Non-privileged migrants are compelled to a spectral existence, partially hidden from sight by border politics and the spaces migrants are confined to during forcibly clandestine journeys, detention, even reception ‘centres’ (mostly keeping their inmates at the periphery of societies), and the usually hidden process of deportation. All too often, migrants are also forced to walk a thin line between life and death; all too often, the borders are haunted by those who were killed in the attempt to cross.

The film makes a further connection to the spectres of history: by turning to black and white and a 16mm camera at the end, the images from the refugee camp become reminiscent of past documentaries. In the poetic voice-over, these images are explicitly linked to the history of the Holocaust. The trains become memories of ‘forgotten trains’—a central symbol of the National-Socialist mass deportations to the extermination camps. The text mentions the suicide of Walter Benjamin in Portbou at the French-Spanish border in 1940 “on the day they closed the borders”.

Resistance: Inside the Border

The trains in the film, however, also become a symbol of the potential for resistance. In Idomeni, the border is closed for migrants but trains delivering goods are passing, their tracks crossing the refugee camp. The film shows the formation of a protest against being trapped by the closed border by sitting on the rail tracks and blocking the trains. The refugees create a human border in protest against the inhumane closure of the border, a border inside the border. They use their mere bodies as a means of resistance in an unexpected reversal of border politics which use the restriction of physical movement, the literal arresting—that is, stopping—of bodies as a form of control and submission.

This act of resistance poignantly demonstrates the contradictions of a world where goods and capital travel freely while human beings can be brutally restricted in their movement. It also hints at the interconnection between these contradictory situations. In the capitalist system, everything and every human being is evaluated according to its economic use. By rendering the trains useless, the system is jarred, and an opening may become visible for a different system, a system where economic concerns are not predominant, where the needs and desires of humans are at the core, not the preservation of national economies whose success is based on the exploitation of the majority by the few.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The cold functionality of capitalist trade: the train moves, the person cannot move; trade is ‘free’, human beings are not.[/beautifulquote]

The ‘arrested’ bodies of the refugees in turn arrest the movement of capitalist trade. Thereby, they highlight its cold functionality: the train moves, the person cannot move; trade is ‘free’, human beings are not. Governments decide about immigration on the basis of economic usefulness: when there is a shortage of workers, immigrants are invited; when immigrants are not seen as economically useful, that is, as exploitable for the profit of others, they are excluded with the brutal force of border politics with often literally fatal effects.

The human blockade of the train is a political moment in a positive sense: those who are excluded, not only from entering certain countries but from the whole sphere of political visibility, manage to create a new political space.* The occupied rail tracks become a scene of political intervention – through physical resistance, but also through signs of protest and, most powerfully, through becoming a space of democratic deliberation in debates and political negotiations: the chanting of “open the border” is stopped in order to listen to and discuss objections against the protest. In this way, the migrants, having been turned into spectres by the border regime, reaffirm their status as political subjects, not of a specific nation state, but of a new, perhaps utopian, political realm.

Politics: the Spectre of Communism

This is where the film’s title as a reference to the famous first sentence of the Communist Manifesto becomes meaningful: “A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.” The spectre in the Manifesto is one of a political force, of the formation of a new political subject which is able to unsettle no less than the whole set-up of the existing economic-political system. It is the spectre of those structurally suppressed and exploited becoming conscious of their shared aims and getting ready for a radical political struggle. Can we see parallels to the situation in the film, to the situation today?

The Manifesto goes on: “All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre”. This can be read as a striking parallel to the fact that all the powers of current Europe seem to form an unholy alliance to exorcise the spectre of migration, not by allowing migrants to move in a non-spectral, safe way, but by trying to stop them from moving, by trying to restrict the spectre to its outside, not its borders, but even further removed, where ‘we’ Europeans, ‘we’ privileged non-migrants or migrants, do not have to see them, where they are exorcised.

The Manifesto continues:

“Two things result from this fact:

- Communism is already acknowledged by all European powers to be itself a power.

- It is high time that Communists should openly, in the face of the whole world, publish their views, their aims, their tendencies, and meet this nursery tale of the Spectre of Communism with a manifesto of the party itself.”

The aim of the Manifesto, then, is to bring the spectre out into the light, to reveal the actual aims of communism—not as a vague threat haunting everyone, but as a threat to those in power and to a system upholding hierarchical power and economic inequality. A power against the powers of oppression. – Can the spectres of migrants be seen in a similar way? Can the appearance of migrants be considered a power of sorts? Or would this be an idealisation or even an instrumentalisation of the plight of refugees?

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The realisation of the power of this oppressed mass to stop the workings of the system exploiting or—in the case of migrants—excluding them can become a political force: for the workers, this power is the strike, for the migrants in Idomeni, it was the blockade of the trains.[/beautifulquote]

As the workers at the time of the Manifesto were placed together in the large sites of industrial production as “masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, […] organised like soldiers”, migrants are also pushed together as a mass with the attempt at rigid organisation and control. From an economic perspective, they are the mass of the ‘useless’, the mass of those superfluous as far as the functioning of capitalist exploitation is concerned. As with the proletariat, however, the realisation of the power of this oppressed mass to stop the workings of the system exploiting or—in the case of migrants—excluding them can become a political force: for the workers, this power is the strike, for the migrants in Idomeni, it was the blockade of the trains. The wheels of the system stood still—for a moment at least.

Spectres of Utopia?

In her poignant text We Refugees, Hannah Arendt provocatively refers to “refugees driven from country to country” as “the vanguard of their peoples—if they keep their identity”. The voice-over text in the final part of the film also engages with the question of ‘them’ (migrants, refugees) becoming “like us, quiet and unliberated and lifeless, gradually till they forget who they are and where they came from”. At first, it seems problematic to ask refugees not to become “like us” or to retain “their identity” when the predominant call is for ‘integration’ or ‘assimilation’ and maybe even the main desire of migrants is precisely to become ‘like us’, if ‘us’ are the privileged residents of host countries. But as a politicisation of the role of the migrant, a perception of its ‘vanguard’ status, this is an important reflection.

Arendt observes that the system of nation states is unable to deal with the situation of the appearance of stateless—and rightless—people on a large scale. She sees the Jewish people forced to flee by the National Socialist system and then being left in a precarious state in the countries of exile as a vanguard of a dystopian situation where starting with “the weakest”, everyone is in danger of experiencing such a fundamental loss of rights, of becoming an outcast. If we do not prevent human beings from becoming such outcasts, anyone can ultimately become an outcast, an outcast who is stripped of their humanity, or else they become part of those who cast out, those who give up their humanity through the absence of empathy. A spectral world, indeed.

If refugees and migrants do not simply “become like us”, forgetful of a system which will keep producing its outcasts, and if we join them in remembering this scandal of ‘our’ world, the ‘vanguard’ of refugees like the ‘spectre of communism’ may become the sign of a new beginning, of the possibility of a different world.

Like the proletariat which represents the structural scandal of the capitalist system, the systemic exploitation of the majority, the situation of refugees in the space inside the border, so to speak, stateless and powerless, reveals the very roots of suffering and suppression in this social world: the fact that the needs, wishes and interests of humans ultimately do not count.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]If refugees and migrants do not simply “become like us”, forgetful of a system which will keep producing its outcasts, and if we join them in remembering this scandal of ‘our’ world, the ‘vanguard’ of refugees like the ‘spectre of communism’ may become the sign of a new beginning, of the possibility of a different world.[/beautifulquote]

Refugees may be seen as the vanguard of an increasing number of superfluous people, for instance of those rendered useless for the capitalist system by automation and the matching planning of capitalists, oriented solely towards a reduction of costs and an increase of profit. It is high time that we, migrants, privileged or not, ‘residents’, privileged or not, join the political subject visible in the train blockade in the film: a subject which radically questions the logic of the existing order. This joint political subject challenges the very basis of the global order of inequality: capitalism and its political institution by capitalist nation states. Such a movement points towards the necessary utopia of global equality, internationalist solidarity and democracy. It is a radical opposition against a world in which the other either appears as a competitor or as a ‘burden’. Its utopia is a world where the other appears as a human subject, an equal in dialogue and collaboration, a possibility for encounter, exchange and a shared life—a shared political life in a positive sense.

The reflections at the end of the film also emphasise “the political” as a “desire” which “we” seem to have “lost”. The mostly dark tone of the voice-over in these final passages of the film and the eerie black and white images are counter-acted by the depiction of the people in the camp who are often laughing, smiling, children are playing, people are sitting together talking—as if to say, humanity is not lost (yet).

Watching this film together in the setting created during “Utopian Nights: Inside the Border” on Thursday, 2nd August, in Howard Gardens, Mdina, promises to be a political moment in a positive sense: the possibility of experiencing and discussing the film with others in an atmosphere which somehow mirrors that of the film—a makeshift political space of encounter, democracy and utopian imaginings.

* For the notion of politics as an act of creating new political spaces and making visible what was invisible within the political sphere before see Jacques Rancière’s works, for example, Ten Theses on Politics. Trans. Davide Panagia/Rachel Bowlby. In: Theory and Event 5.3 (2001).

Kathrin Schödel lectures at the Department of German, University of Malta; her research interests are literature and politics, depictions of revolutions, constructions of gender roles, discourses of migration and utopian thought. She is a member of CAUR (Centre for Applied Utopian Research).

Leave a Reply