How did it happen that everything previously labelled as misery and poverty became symbolic of good intent and care for environment in just a couple of decades? Progress: it seems that we have been there without knowing.

by Raisa Galea

Collage: Isles of the Left

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]nyone acquainted with Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being would certainly remember its most striking chapter, featuring the dictionary of mutually misunderstood words that Sabina and Franz shared. Their social and individual upbringing was reflected in how they interpreted everyday habits and events.

Having grown up in Switzerland, Franz saw the people of communist Czechoslovakia living a ‘real life’ he had never experienced while Sabina thought that the drama of her country was ugly and devoid of romance. Marches and demonstrations excited Franz; to him, they were a uniting and liberating force. Sabina could not agree less. Since she was obliged to march, it was kitsch—not emancipation—that the May Day demonstrations epitomised.

This little dictionary of Sabina and Franz brilliantly captures how the very same artifacts and events can mean different things to different people. What signifies ‘progress’ to one may well be ‘decline’ in the eyes of another.

![]()

It has been a few years since I began to see familiar everyday artifacts and customs in different light. I could understand the perspectives of both Sabina and Franz, each willing to exchange and trace the ephemeral symbolism of things. Ironically, everything that was mocked as regressive in the time of my childhood now embodies eco-awareness and a forward-minded vision for the future. And vice versa—what now reads as ‘progress’ was disdained as backwards in a not-so-distant past.

My childhood coincided with the era of the USSR’s demise and was characterised by such attributes as cloth bags, reuse of just about anything, state-supervised recycling of glass, metal and paper — all that is part of European citizen’s mundane experiences today. Some habits of those days resembled the contemporary environmental ethical code: we used no extra packaging, for example. Butter was sold by weight and wrapped into baking paper while vegetable oil was poured straight into the empty bottle you were expected to bring with you.

My grandparents did not call to abolish extra packaging and single-use plastic because these items were simply not available.

Everyone went shopping with a cloth bag. Despite their outer similarity, there is a wide ideological abyss between the cloth bag in my childhood and that in today’s Western societies. While today a cloth bag channels eco-awareness and deliberate refusal of plastic, to my grandma it was only a practical means of bringing the shopping home. My grandparents did not call to abolish extra packaging and single-use plastic because these items were simply not available. They did not protest supermarkets because those were not around either.

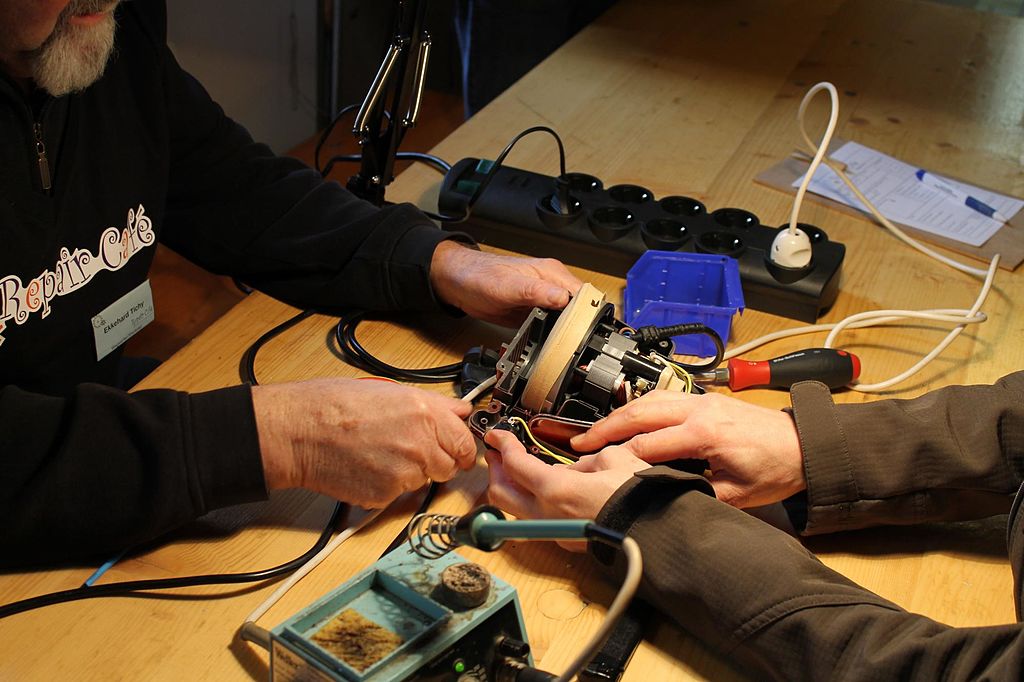

Upcycling in the USSR wasn’t a matter of hip fashion. There was no need for repair cafés: fixing broken appliances was the rule that people lived by. Reinventing pellets and pieces of fabric into a furniture piece was driven by necessity and the lack of alternatives, not by optional creativity as it is today. Nobody called it ‘vintage’ and clasped their hands in delight when I wore mum’s (hand-sewn, excellent quality) clothes to school. Indeed, in times of total shortage of goods and deep economic, political and social crises, garments from grandma’s wardrobe were looked at as old-fashioned and beggarly.

The USSR had a robust glass recycling framework whereby clean empty bottles were exchanged for small cash. Until a few years ago, a glass bottle return and reuse system existed in Malta as well, yet it was brought to a halt in the name of free market. Oh, the fickle symbolism of progress! Who would have thought that single-use plastic bottles will soon become old hat or the infamous Benna’s rebranding would even spark a public outcry?

As a child, I firmly believed that cloth bags, recycling, upcycling and the absence of supermarkets were painfully outdated.

These twisted déjà-vus leave me confused time and again. As a child, I firmly believed that cloth bags, recycling, upcycling and the absence of supermarkets were painfully outdated. They belonged to the communist past which, we were told, was one big disgraceful mistake. Back then, it were jeans, Italian shoes and plastic bags with prints of New York’s skyline that manifested progress.

How did it happen that everything previously labelled as misery and poverty became symbolic of good intent and care for environment in just a couple of decades? When did the habits so intrinsic to the much-maligned planned economy turn into fashion trends and key elements of the prospective circular economy, so lauded by progressives of all stripes? Progress: it seems that we have been there without knowing.

![]()

Looking back at the years of my childhood, I do not feel nostalgic. Not only did we not denounce consumerism—we dreamt about it. I recall the empty shelves of the local grocery stores and the never-ending, hundred metres-long queues, which were an obligatory attribute of every shopping procedure. During the years of the USSR’s collapse, queues were the public space: they were children’s playgrounds and served as meeting points for heated debates on the crippling social insecurity that was taking us all by storm. Thus, ‘consumerism’—spelled in bold and caps—was the neon dream of Western capitalist abundance. We longed for it.

Neither did we campaign for reducing meat in our diet. Just like the meat on baroque still-lifes signified high social status of their owners, in the USSR its provision index was one of the standard measures of the country’s well-being. It was hard-to-get, especially good quality beef and pork, therefore consumption of it wasn’t hitting the sky. In fact, if in 1970 meat consumption in the USA was 106.1 kg per person annually and in the UK — 74.3 kg per person, in the USSR this value was almost twice less — 48.6 kg per person.

Meat meant prosperity, full stop. Everyone tried to make acquaintance with a butcher to gain better access to a piece of animal flesh, which was both a basic need and a luxury. A festive table was unimaginable without meat and, specifically for the reason of its poor availability, its presence on a plate was an additional reason to celebrate.

Although meat is no longer rarity in present day Russia (and neither is it in Malta), flashbacks to the times of its scarcity are still circulating in the collective memory, and I too happen to be reminded of its deep-rooted ideological significance.

On a train trip from Moscow to Astrakhan a few years ago, a stewardess delivering lunch to the travelers was seemingly proud of the meal’s dignified ingredient — meat. When I politely turned it down admitting that meat had been off my plate for a while, she took my reply as a personal offence. Until the end of the trip, she muttered reproaches on the lines of how-overly-satisfied-with-life-one-must-be-to-refuse-the-gifts-of-good-life-with-no-starvation every time passing by my compartment.

To all who experienced years of forced austerity, progress could be incompatible with rejection of consumerism and self-imposed frugality.

The clash of ideologies revealed by this accident goes far beyond meat in my train lunchbox: To all who experienced years of forced austerity, progress could be incompatible with rejection of consumerism and self-imposed frugality. After the decades-long reign of the free market logic linking progress to abundance of commodities, the arguments in favour of reducing meat consumption, fixing clothes and appliances seem contrary to what used to exemplify progress for so long.

![]()

It’s no secret that our mundane desires aren’t just influenced by personal preferences but largely reflect the common ideas of prestige. Flaunted by the elites, conspicuous consumption and wasteful lifestyle were bound to be desirable by the rest. The excessive abundance of Western capitalist societies too became their most successful propaganda tool and, thus, the ultimate symbol of progress worldwide, until it was recently brought to question.

On the other hand, the habits that now embody eco-consciousness had existed long before they were rediscovered by our contemporaries. Frugality had always been part and parcel of our grandparents’ way of life; that is, before they were led to leave it behind in the name of growth and ‘progress’. Conversely, the middle class in economically advanced countries embraced upcycling, recycling and began challenging the ideal of consumerism with relative ease because they had never been forced into these practices by poverty and deprivation.

If conducted for the sake of environmental sustainability, self-imposed frugality is nevertheless futile because it can only happen in circumstances of abundant consumer choice, and thus, growth.

Though it was beneficial for the environment, shortage of goods and a low-meat diet were not embraced by the citizens of former communist states. Mandatory, imposed rules are destined to breed rebellion. On the other hand, the contemporary eco-conscious lifestyle appears to be more democratic: it is performed by choice. Yet, if conducted for the sake of environmental sustainability, such self-imposed frugality is nevertheless futile because it can only happen in circumstances of abundant consumer choice, and thus, growth.

As good as it might look, consumer activism will not save the planet: anything manufactured has already taken up resources and will eventually become waste, whether it is purchased or not.

Given the absolute urgency of moving away from the mantra of growth and capitalism, can reduction of consumption to ecologically-sustainable limits still be a matter of individual preference? I believe not.

Eco-austerity—egalitarian rationing of resources coupled with care economy—is one of the decisions the economically advanced societies ought to make if we are to radically transform the status quo that is pushing us into the abyss of climate calamity. And this obligatory step must now be made by the affluent: it turns out that the regular citizens worldwide are already living frugally—austerity governs much of their lives, albeit not by choice.

Leave a Reply