In the past few years, Malta championed the cause of gender and sexual minorities. However, when it comes to their de facto representation in the media, the progress has been much slower.

by Marthese Formosa

Image: Reuters/PIXSELL

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]ndoubtedly, when it comes to LGBTIQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex and queer) rights, no one can dispute that Malta has seen a shift in terms of recognition of gender and sexual minorities. Let me start by outlining the legal changes that Malta underwent since 2012.

The early signs of the forthcoming changes in legislation emerged from the debate on the status of same-gender couples in the Cohabitation Bill of 2012; this paved way to the Cohabitation Act of 2016 which fully acknowledged them. In 2014, the definition of Hate Crime and Hate Speech in the Criminal Code of Malta (Article 82) was amended to accommodate hate speech against sexual orientation and gender identity, thanks to the EU’s commitment to the cause. This was followed by the Civil Unions Act of 2014—both the result of an electoral promise and the work of the LGBTIQ Consultative Council. The Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act of 2015 (GIGESC) provided, for the first time, protection to Intersex people (especially infants). Such a framework was significant as it legally recognised various gender identities beyond the cisgender (those whose gender identity aligns with the gender assigned at birth) and the normative male-female binary. Subsequent changes, such as the ‘X’ marker on legal documents and inclusive education have been the result of all of these legal changes.

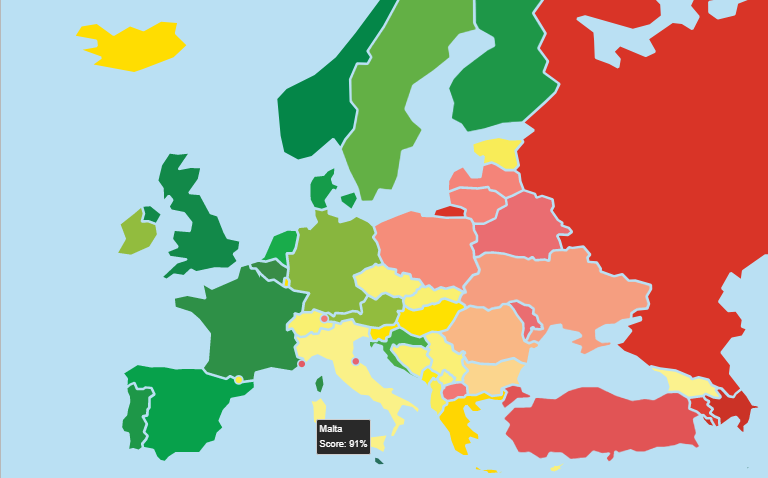

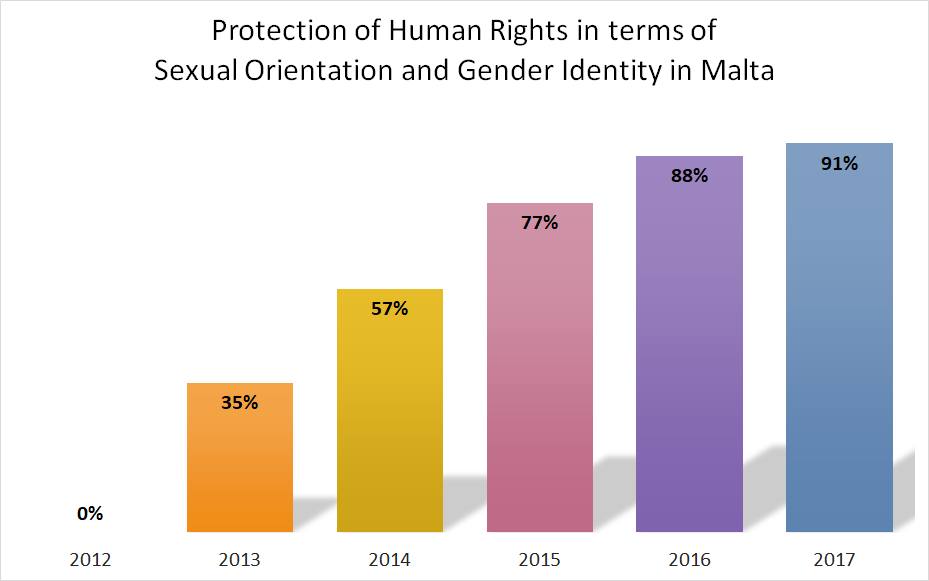

This has put Malta on the EU map as a stronghold of sexual and gender rights and equality. The changes can be visually tracked using the ILGA-Europe Rainbow Map which reflects the legal and human rights status of LGBTI people in Europe. The methods used to evaluate the status of the LGBTI rights have varied from year to year but the scores are comparable nevertheless.

The chat below illustrates the progress of Human Rights protection in terms of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI). For the past three years, Malta has been in the Top Three EU countries on this criterion: it ranked 3rd in 2015 and 1st in 2016 and 2017.

However, when it comes to de facto presence of sexual and gender minorities in social surveys, leisure, public places and the media, things have been slower. For example, state and private polls usually provide only two options for gender—‘Male’ or ‘Female’. Rarely are there other options and when there are, it only applies for health surveys which tend to research gender identity.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]How many same-gender couples are seen holding hands in public? How many grooming services offer gender neutral options?[/beautifulquote]

When it comes to leisure and public places, how many of them offer a safe space for queer (an umbrella term for sexual and gender minorities who are not heterosexual and/or not cisgender) people? Will leisure venues close down after a few years? How many same-gender couples are seen holding hands in public? How many grooming services offer gender neutral options? And clothing outlets? How many gender neutral or gender-inclusive bathrooms exist?

There is still much to be done. With inclusive public and corporate frameworks, education and diverse media representation, the public could have access to better information. Research-based awareness and campaigning through role models could have made a positive impact on collective consciousness. Yet, despite the fact that LGBTIQ people are invited for interviews which feature in TV programmes and documentaries, representation of these minorities by other kinds of media, such as prose, poetry, novels, and entertainment (e.g. drag king shows, plays, etc.) is still lacking in Malta.

For instance, if you watch Maltese dramas and comedies, can you think of at least three queer characters (on any spectrum) that appear on TV. How are they portrayed? While it’s okay to fit in a stereotype, there should be various representations like those that reflect the objectively existing diversity of heterosexual and cisgender people. And what about educational books that explain different relationships to children and young adults at school? This is important as, nowadays, alternative family formations are becoming the norm.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Almost none of queer relationships, depicted in Maltese fiction books, were happy ending.[/beautifulquote]

Moreover, how many Maltese novels feature queer characters or plots? I was curious. Thus, I compiled a list of books written by Maltese/Malta-based authors who included queer characters in their stories. The list was rather limited. Almost none of queer relationships, depicted in these fiction books, were happy ending—the children’s books Mamà, allura din imħabba? and Truly Willa are highly recommended though. I prefer to have a broader selection of reads that have queer characters. Such diversity is important and needs to be represented better in fiction!

Although there’s nothing wrong with voicing our opinions in order to be heard, I’m not writing this just to be critical. After having noticed that several authors—especially queer youth, thanks to fan fiction culture and online tools,—do write on LGBTIQ topics, they tend to publish under a pseudonym or don’t acknowledge that they are Maltese. This suggests that that these authors still fear being ousted publicly because there is little Maltese queer fiction. On a personal note, as someone who is into reading queer fiction, I noticed how badly this has affected my Maltese language as I hardly find anything of interest to read in my mother tongue.

It couldn’t be just me who’d wish to read more queer fiction in Maltese or by the local authors. It couldn’t be me alone demanding comics with queer characters written locally (which would have further improved the chance of obtaining an autograph!) or enjoying beautiful illustrations that are queer inclusive.

So I have joined efforts with like-minded individuals and designed a project called We Are. We succeeded to receive funding (supported by Malta Arts Council—Creative Communities) and we aim to continue fundraising in order to further our queer agenda. We came up with Kitba Queer, which seeks to create the first bilingual Maltese Queer Fiction Anthology. The initiative will produce queer fiction of entertainment value to supplement the existing academic initiatives, such as the Queer 360° Conference and research projects of university students.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]With little queer representation in society, collective perception will not shift.[/beautifulquote]

Kitba Queer organises workshops that are open to the public, while the Anthology features literary pieces by people that in some way or another identify as queer. We felt the need to carve out a queer safe space in the literary scene as it is currently non-existent. The workshops are open to anyone, since anyone can create queer characters in the future (hopefully sensibly and humanely).

Ultimately, with little queer representation in society, collective perception will not shift. People are still scared to be themselves publicly, including all those authors who feel the need to hide behind a pseudnym. While LGBTIQ rights are a great framework, they are not the canvas stretched in between the frame which is our life.

![]()

Marthese Formosa has been active in civil society for the past years. She is interested in anything related to the environment and queer issues. On a more personal level, Marthese enjoys reading, taking too many photos and collecting scarves.

Leave a Reply