It is through re-establishing compassionate connections between people and abolishing the social hierarchy that nature can once again be valued.

by Martin Galea De Giovanni

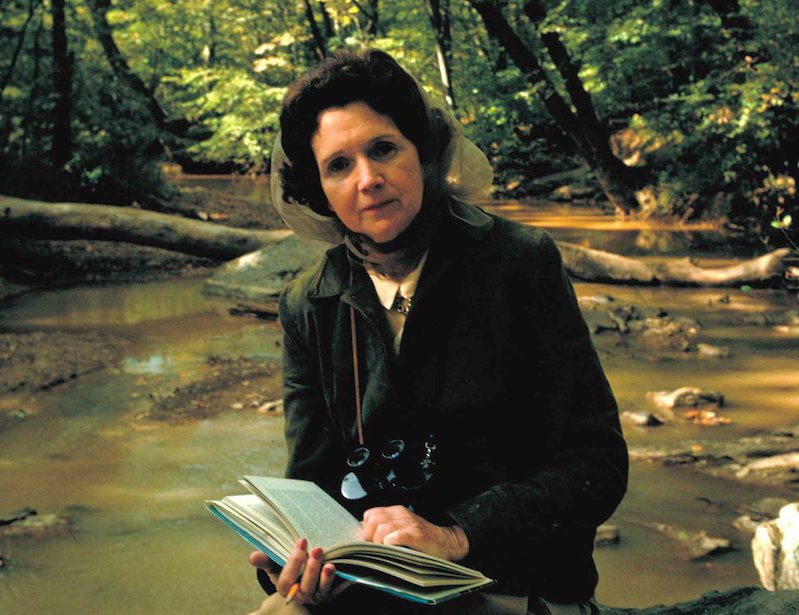

Artwork: Oceanic Woman by Françoise Gilot

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]omen are disproportionately affected by environmental injustice, climate change, natural disasters and the exploitation of nature. This is especially so for women of colour, indigenous women, LGBTQ women and working women. Despite (or perhaps due to) this vulnerability, women have been protagonists in the defence of communities and the struggles for autonomy.

The aspirations for women empowerment and the objectives of environmental justice affiliate harmoniously within ecofeminism whose worldview stems from an understanding that nothing in nature takes place in isolation. Everything is inherently and intrinsically connected to something else and hence ecofeminists perceive the domination of nature as an extension of human desire to dominate each other through contrasting “dualisms” such as man and woman, parent and child, master and slave, and other forms of hierarchical power structures.

Ecofeminist worldview stems from an understanding that nothing in nature takes place in isolation.

The term ecofeminism was coined by the French writer Françoise d’Eaubonne in 1974. This was followed by Theodore Roszak who referred to ecofeminism as the “return of the Goddess”. Other prominent ecofeminists include Susan Griffin, Carolyn Merchant, Riane Eisler, Marija Gimbutas, Vandana Shiva, Janet Biehl, Judi Bari and Carol Warren.

In tracing the environmental thought within a homocentric/androcentric outlook, ecofeminists believe that it is through re-establishing compassionate connections between people that nature can once again be valued. If one had to abolish patriarchy, this could potentially lead to a just society living in communal harmony. This could advance to a shift in core values toward prioritising of quality of life and the wellbeing of our communities over wealth accumulation and expansion economics.

Similarly to the other grassroots environmental justice movements, ecofeminism is also critical of hierarchy, but in this case, the focus is on one particular type of hierarchy: this philosophy holds patriarchy as the fundamental cause of inter-human injustice and environmental decline.

Since humanity in each of us is shaped by symbols, rituals, ‘myths’, language, and relations to our physical surrounding, consequently, our relationship with nature, too, is greatly affected by dominant cultural paradigms. Thus, normalised since the Biblical times, the Western patriarchal dominance over women and nature deeply impaired our ability to engage with the natural world. Ecofeminists insist that it was the influence over the scientific method and rational analytical thinking—which they define as male and which neglects nurturing, care and intuitive wisdom often mistakenly categorised as exclusively “feminine”—that has led us to the current environmental crisis.

Ecofeminists insist that it was the influence over the scientific method and rational analytical thinking—which they define as male and which neglects nurturing, care and intuitive wisdom often mistakenly categorised as exclusively “feminine”—that has led us to the current environmental crisis.

The conception of nature as feminine, personified in goddesses and sacred female-shaped figures of the ancient time, allows to see the parallels between the oppression of the earth and that of women. Just like the goddesses, the Greek words that constitute ‘ecological wisdom’—Gaia and Sophia—are of feminine gender. Feminism and environmentalism have another common link: environmentalism as we know it is widely credited to the efforts of a woman, Rachel Carson, who combined her rational scientific training in biology and her active role as a political activist with the more ‘feminine’ emotional sensitivity to the world of nature.

Ecofeminism is deeply influenced by the broader feminist and anarchist thought to the extent that its followers are acutely aware of and actively contesting hierarchical and sexist social practices.

It is the awareness of broader social injustice that distinguishes radical ecofeminism from the nature conservation movement which is generally based on conservative notions of tradition and cultural value. The latter also believes that the ecofeminist movement is distracting environmental campaigning from its biocentric ideals. Counter to this, ecofeminists have also been critical of particular types of environmentalism such as that directed by the Earth First! Movement, which they described as being “led by boorish and sexist men”.

It is the awareness of broader social injustice that distinguishes radical ecofeminism from the nature conservation movement which is generally based on conservative notions of tradition and cultural value.

On the other hand, environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth International recognise the revolutionary potential of ecofeminism and believe that social and environmental justice is only achievable through a radical transformation of our societies. They actively seek justice and freedom from all systems that devalue and exploit women, peoples and the environment, including patriarchy, racism, neo-colonialism and neoliberal capitalism. These systems cannot be tackled in isolation; they reinforce one another in the constant drive for material accumulation and profit for the few.

Leave a Reply