Ghost in the Shell: a transmedia franchise nearly 20 years old, yet relevant more than ever with its transhumanist themes, cyberpunk stylings and, perhaps most importantly, kickass female figure known as the Major. But what is it all about? Jack in for a closer look at a vision of the possible near future…

Ghost in the Shell: a transmedia franchise nearly 20 years old, yet relevant more than ever with its transhumanist themes, cyberpunk stylings and, perhaps most importantly, kickass female figure known as the Major. But what is it all about? Jack in for a closer look at a vision of the possible near future…

by Marco Attard

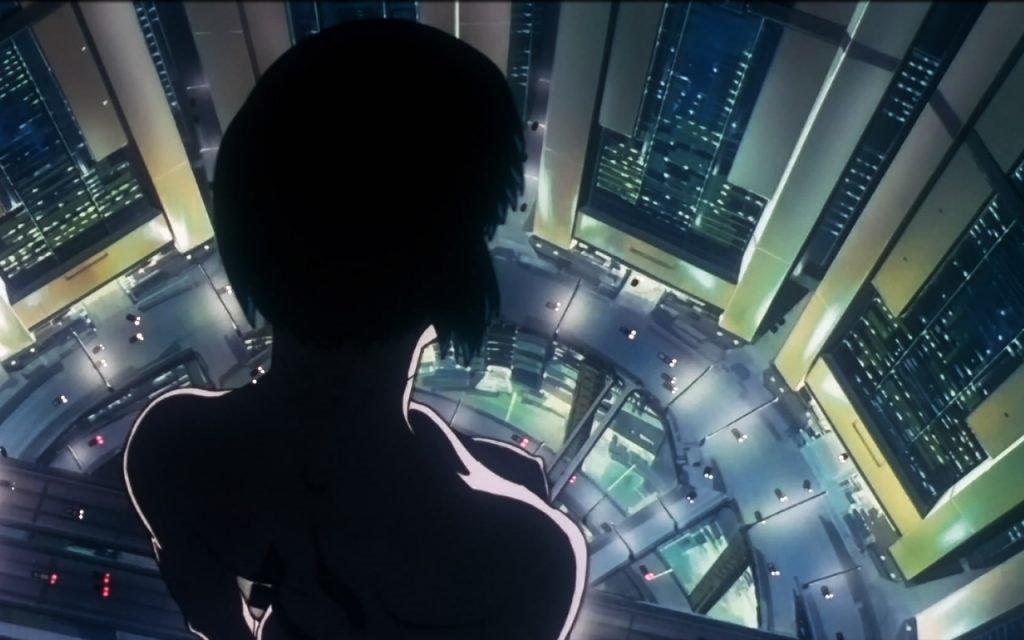

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t’s one of the most memorable openings from not only animation, but arguably cinema in general. A woman sits perched atop a skyscraper in a futuristic metropolis, spying on what sounds like political intrigue taking place in one of the floors below. She stands and takes off her coat, revealing she’s seemingly wearing nothing underneath, other than gloves and boots, and swan dives right off the building. In the meantime, police storm the building, leading to one of the participants of the aforementioned intrigue to claim diplomatic immunity. Just as he does so the video wall behind the diplomat shatters and his head explodes like a piece of overripe fruit. It’s the naked woman, who looks straight into the camera, wipes her face with an invisible hand and vanishes into the city below. Cue chimes, quasi-religious chanting and the title: GHOST IN THE SHELL.

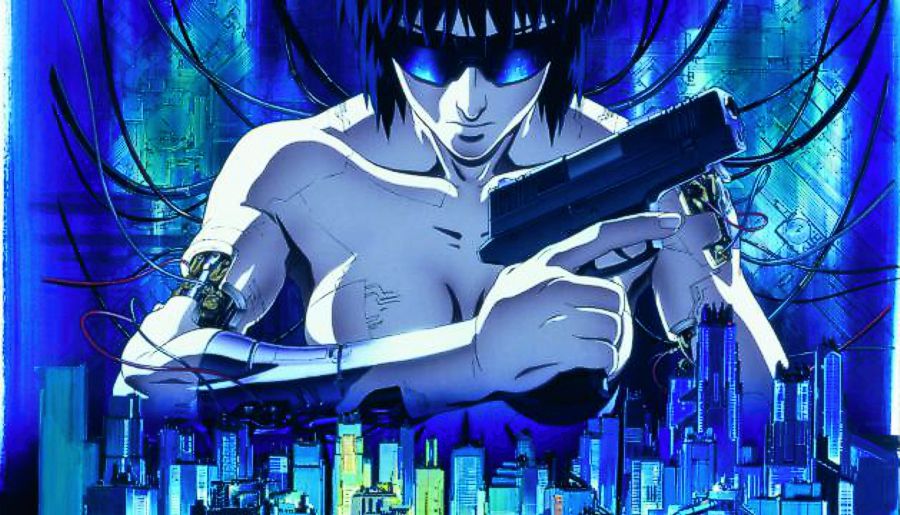

The 1995 Ghost in the Shell movie was many people’s – including my own – introduction to the character known as Major Motoko Kusanagi, strong anime female character par excellence and bearer of one of the finest haircuts out there. However, before going through the film I think it’d first have a look at her first appearance in the manga, 攻殻機動隊/Kōkaku Kidōtai, or “Mobile Armoured Riot Police,” a name so prosaic it makes a 180 degree turn and sounds kind of cool.

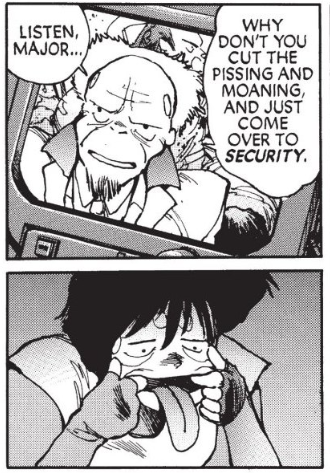

First serialised in 1989, the comic is a series of short stories set in a “near future” anarcho-capitalist Japan ruled by massive corporate conglomerates with little to no government oversight. The stories star Section 9, an anti-terrorist unit led by Motoko Kusanagi, aka The Major. The very first comic chapter tells the same events as the animated film adaptation’s opening, and states the name is “obviously an alias.” It also suggests the “female model cyborg” might even be operated by multiple women.

Over the course of the 300+ pages making the first comics volume of Ghost in the Shell the reader gleans at least a little about the character. In the least she’s certainly superbly capable both in terms of real-world and cyber-warfare and her leadership of Section 9 is never questioned – despite its being composed wholly of men. She also has something of a friendship with Section 9’s Dolph Lungren-lookalike Batou, enjoys a drink or three and is bisexual, dating multiple women and at least one man. But the comic is in no way a character study – the proceedings are so fast paced it feels like its creator Shirow is all too eager to bounce from one thing to a next, be it his many ideas on technology, transhumanism, philosophy and politics of the future, action involving robots and futuristic weapons, goofy jokes or simply drawings of sexy ladies.

Coming from the comic to the 1995 animated Ghost in the Shell movie remains, to this day, a bit of a shock; whereas the comic is an action-packed and often humorous romp with some clever ideas, the movie is essentially a serious action film with the languid pacing of a European art house piece. Sure, there are bursts of action, but these are mere punctuations to lengthy sequences where characters simply… talk. What do they talk about? Mostly the existential horror of being a cyborg. The mechanical bodies of the likes of Kusanagi and Batou are hugely expensive things, built by corporations and owned by the government that employs their users. Motoko believes she does not even own her thoughts – produced as they are by a brain whose matter has also been enhanced by her employer – and as such the only thing she can truly call her own is her “ghost,” a spiritual essence that’s beyond the physical.

It is no surprise that Mamoru Oshii’s film incarnation of The Major has little time for friendship or booze or sex or cheekiness; what good are alcohol or sex for a mechanical being? Stripped of anything that could humanise her, Kusanagi is, essentially, a ghost in a shell. She is still more than competent at her job, of course. As animated by Production IG, her proportions are more naturalistic and, refreshingly, not as sexualised as those in the manga. She wields her body with efficiency and purpose, applying violence with both power and precision whenever required – and the film subtly highlights just how powerful the Major is, as her leaps cause concrete and metal to crack, and her hand-to-hand combat is even more brutal in just how casual she makes it look.

Both comic and the animate Ghost in the Shell ends the same way. Circumstances force Kusanagi to deal with the Puppet Master, a military experiment in artificial intelligence gone rogue. The AI is clearly fascinated by Motoko, and suggests a proposal to her – a merger of artificial and human minds in the name of creating something new. For the film’s version of Motoko, the decision is perhaps obvious – following a fight against a gigantic spider robot, her body is left shattered and the authorities are on the way (in the comic the situation is more complicated, but essentially Motoko ends up in trouble with both the government and the corporations it is beholden to, and needs a means of escape). Through Batou’s help the result is transcendence as Motoko becomes something new, neither the Major nor the Puppet Master, but a being able to live freely in the “vast and infinite” world wide web.

Poor Ghost in the Shell 2017, unwanted and unloved despite Scarlett Johansson starring as the Major and some remarkable production design. The controversy surrounding Johansson’s casting as what is nominally an Asian character is perhaps warranted, although I don’t feel in any qualified to comment on it. That said I’ll also admit ignorance in not knowing of a Japanese actress able to bring what Johansson does in as Kusanagi. Her performance brings a level of alienation and purpose-driven motion equivalent the animated equivalent and that, I feel, is something of an achievement. There’s some excellent, if all too short, moments with Johansson simply walking through the film’s futuristic Hong Kong where the film feels like a worthy adaptation. However most of the time the proceedings are just deeply average, as the Major is morphed into Campbellian hero complete with origin story, something that lessens the character’s staying power.

Whereas the finale of both manga and animate incarnations of Ghost in the Shell conclude with Motoko transcending the limitations of (mechanical) flesh, the live action version ends with their acceptance. The Major accepts her confused origins – a homeless Japanese girl kidnapped by a malevolent corporation, brainwashed into thinking she’s a refugee whose brain was transplanted into a cyborg body modelled after a Western woman after a near-fatal incident – and the film closes direct remake of the opening of the animated film. Johansson’s Major sits perched atop a skyscraper, spying on political intrigue happening within. She stands, takes off her coat and does the swan dive, turning invisible as she descends. Cut to credits and, yes, it’s that same quasi-religious music from the first film!

It’s a suggestion of sequels to come, although one wonders if something of the sort will happen. Probably not. In any case the Major lives on, split into multiple creatures roaming the global network known as popular culture – and she remains a cyborg feminist icon to this day. Does she qualify as such, though? As defined by Donna Haraway in “A Cyborg Manifesto,” the cyborg is a “blasphemous, ironic, rebellious, and incomplete entity” – something I believe fits more the version of Motoko from the manga, rather than the film. That said the two versions of the character certainly express a rebellious streak by the end, and both manage to achieve full liberation from an oppressive and militaristic society. On the other hand, the live action version goes in the opposite direction with her acceptance of her status of authority-owned weapon. No wonder; the live action film is a product of the Hollywood military-entertainment complex, after all. The Japanese versions, while bearing a fetish for military hardware, are not.

A work made by an artist with a singular version can afford to have a rebellious streak. A corporate product cannot.

Marco Attard, 新浜市, 2018

Leave a Reply