The growing discrimination, harassment, attacks and assaults are not bound to one social category (such as gender) but to multiple at once—age, race, class. Queer-feminist street art is a response to such harassment in public space.

The growing discrimination, harassment, attacks and assaults are not bound to one social category (such as gender) but to multiple at once—age, race, class. Queer-feminist street art is a response to such harassment in public space.

by Kl.Aus

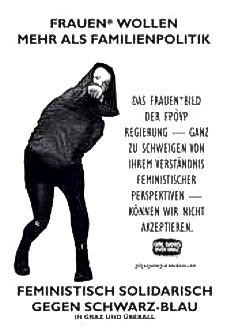

Images: Girls Gangs over Graz

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the course of Moviment Graffitti’s program on and around the 8th of March, a talk on queer-feminist street art against street harassment took place in Valletta. The extensive discussion made clear that street harassment as a repressive behavior is not a widely spread topic in public discourses in Malta. Furthermore, the discussion articulated a need for intersectional and queer-feminist analysis and actions. This article is a summary of the theoretical input of the talk on street art strategies of Grrrl* Gangs over Graz (Austria) as a queer-feminist reclaim of urban space. It also tackles the problem of appropriation of feminist actions by the rising far right-wing tendencies in Austrian societies and elsewhere.

What is Street Harassment?

Throughout their lives, most women* and girls* experience unwanted sexualized attention which manifests itself in various forms: verbal, non-verbal, physical, open, but also subliminal, barely perceptible, still encroaching acts. Such sexualized transgression and sexualized violence is ubiquitous, can occur at any time and everywhere and is not only a private matter depending on the behaviour of individual men*. It is a result of power structures and part of systematic social control of women*, girls* and minorities. Those power structures are results of patriarchal relations and its heteronormativity which create norms and tunnel visions of representation and behaviour.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]the affected person should have the right to define where personal boundaries are transgressed and harassment begins.[/beautifulquote]

Street harassment can take many forms and shapes. However, here I focus on street harassment as a form of sexual violence which takes place in public spaces and as essentially a power dynamic that reminds subordinate groups of their susceptibility to attacks and reinforces the omnipresent sexualized objectification of these groups and their bodies. Defining street harassment is difficult but it could include: suggestive glances, whistles, offensive and threatening behavior such as vulgar gestures and sexually charged comments, as well as stalking, public masturbation or assaults. Still, what is experienced as street harassment or not cannot be defined on principle or as universally valid. Even though street harassment and its meaning may be culturally-bound, defining what is exactly experienced as street harassment is subjective. There is no one else but the affected person who should have the right to define where personal boundaries are transgressed and harassment begins.

More problematic than the definition of street harassment is that sexual objectification is so omnipresent that it seems to be an integral part of “normal” female* development. Evaluating gazes of passers-by may be recognized but there is hardly a response to it, because they are an almost normal, everyday experience. Who did not experience being in an unpleasant situation without realizing it right away—until much later, when only the feeling of powerlessness remains? Another aspect which makes public acknowledgement of harassment so challenging needs to be pointed out: victim blaming and shaming does not hold the perpetrator responsible, but the responsibility and blame falls on the affected person. More often than not, this person is blamed for ‘inappropriate’ clothing and behaviours such as being out on their own in at “the wrong time of the day” or in areas that are defined as improper etc.

Power—Space—Gender

Spaces are not neutral. They are culturally and politically loaded. Neither private nor public spaces, as dimensions for social interactions and results of social constructions, are free of power relations, appropriations, norms and behaviour. The interactions in spaces are not random but run along hierarchical structures and inscriptions. Gender and other categories (such as race, class, sexuality) that cause classifying distinctions play an important role in the everyday use of space. Who has access to which spaces and how, is determined by who we are and who is occupying that space in that specific time. Public discourses shape our perception of space. A constant repetition and reminder, which area is not secure for women*, could turn into an actual feeling of danger, discomfort and vulnerability when taking that route.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]security surveillance do not tackle harassment sufficiently since they illustrate the space itself as the cause of insecurity and sexualized violence instead of the underlying societal causes.[/beautifulquote]

Urban planners suggest lights, cameras or women’s* parking lots to solve the problem of harassment. However, these proposals do not tackle harassment sufficiently since they illustrate the space itself as the cause of insecurity and sexualized violence instead of the underlying societal causes. This and other forms of naturalization—throughout which historically constructed differences are perceived as naturally given and internalized as such—need to be discussed in order to fight the implicit inequalities and discrimination. Additionally, such city planning is not democratic as it separates one class from another. Thus, such urban planners are reaffirming those with power and those without, and create spatial inequalities.

We Do Not Want Video Surveillance to Feel Safe! We Want the Space Itself!

This naturalization of spatialities and the apparent normality of sexual assault must be stopped. The light of street lamps does not help (much). The fight requires direct actions, emancipatory practices and empowerment for all concerned—strategies that can be seen on the surface, but go much further beyond that.

This is the goal of Grrrl* Gangs over Graz (GGoG)—an autonomous and anonymous collective of women*: they challenge current political developments by using the streets and their blog as platforms for political expression. They target everyday sexism and create spaces to articulate, criticize and combat the taboo about harassment in its many forms as well as its structural causes. In addition, GGoG address the dichotomy of the public and the private by reclaiming public space and question the (supposed) safety of private spheres into which women* are pushed back.

The action and art forms of the GGoG are versatile. The collective uses life-sized figures of women* in self-defense poses, stickers, posters and other forms of street art to express their ideas and criticism. The actions are on the one hand focused on the practice itself, which brings art and contents into urban space, thus making it the place for criticizing the hierarchical and exclusive spatial distribution. On the other hand, the activities are a way for empowerment and a call for participation in the fight against sexual violence. It is a conscious rebellion against the normalized and oppressive power relations in urban space which manifest themselves in street harassment, other forms of direct or indirect violence and exclusion.

The action and art forms of the GGoG are versatile. The collective uses life-sized figures of women* in self-defense poses, stickers, posters and other forms of street art to express their ideas and criticism. The actions are on the one hand focused on the practice itself, which brings art and contents into urban space, thus making it the place for criticizing the hierarchical and exclusive spatial distribution. On the other hand, the activities are a way for empowerment and a call for participation in the fight against sexual violence. It is a conscious rebellion against the normalized and oppressive power relations in urban space which manifest themselves in street harassment, other forms of direct or indirect violence and exclusion.

In the course of the resurgent (new) right in national parliaments, racism, anti-semitism and anti-feminism are expressed more openly. Women*s bodies are (again) politically discussed (anti-abortion debates) and used for racist discourses against migrants. In Graz, a yellow press paper declared Grrrl* Gangs over Graz and their actions as a way to protect “Austrian Women” against the “dangerous migrant men”. This is false in three ways: Firstly, GGoG never had the (paternalistic) goal to protect women, but to empower them. Secondly, their actions were never targeted “Austrian women” but violent men* and patriarchal structures. Thirdly, GGoG do not consider migrant men* as potentially more dangerous than other men* or harassers. Moreover, the collective clearly distances themselves from any forms of racism.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]feminism has to remain anti-racist; feminists* have to fight against being instrumentalized for right-wing causes.[/beautifulquote]

In protest with the right-wing instrumentalization, GGoG clearly stated that feminism has to remain anti-racist, and that feminists* have to fight against being instrumentalized for right-wing causes. Furthermore, they used banners to make clear that street harassment and sexual assaults are a no-go, no matter which passport the harasser has. Their latest action disputes the election of a conservative and right-wing government (ÖVP/FPÖ) in Austria and calls to articulate criticism and disagreement with its plans which will negatively affect women*, migrants and people in precarious situations.

The current political situation makes a queer-feminist and intersectional standpoint more important than ever. The growing discrimination, harassment, attacks and assaults are not bound to one social category (such as gender) but to multiple at once (age, race, class). Having in mind that different categories intertwine and include this in feminist direct actions is necessary for taking up the fight against the horrific developments in many societies as well as reflecting on one’s own positions of power.

![]()

Kl.Aus – Queer Feministisches Kollektiv für Kleister und Austausch.

Leave a Reply