We’re losing spaces where we can be social human beings. And this is where literature has a space. Authors can identify such cracks and vocalise them.

by Kurt Borg

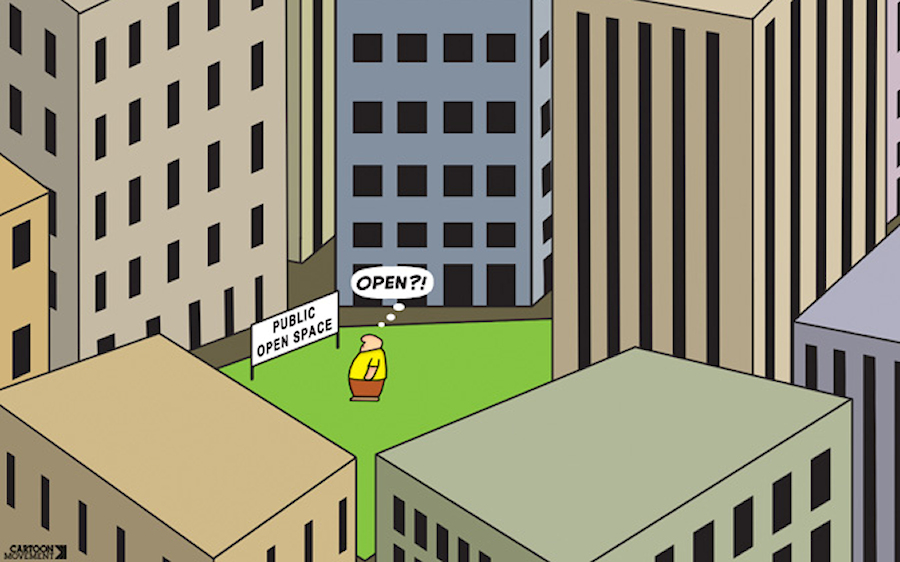

Image: Public Spaces by Steve Bonello (fragment)

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he natural environment has always been a focus of literature. Authors have turned to nature as a source of spiritual renewal, purity and authenticity. The relation of authors to nature has changed because land and seascapes have changed, but nature remains a source of inspiration and concern, a concern transfixed by agony. How does the lack of natural environment and open spaces translate to literature? How do we write trees and fields when trees and fields are no longer? How do we write the colour of the changing sea? Our space and light are being stolen by buildings that reach for the sky. How does literature deal with this daylight robbery? How does it document our struggle for space?”

This was the description of Losing My Space, a pre-event of this weekend’s Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival. The event sought to create a safe space in which to discuss the relation between literature and the environment at a time when such spaces around us are shrinking, with many places being made uninhabitable. Every day we read new stories about protected birds being shot down and dead sea turtles washed ashore. Some of us constantly complain and rant about how various places in Malta feel claustrophobic as opposed to the vast spaces in other countries. We speak of the need for alternative spaces.

The discussion featured Teodor Reljić from Malta and Roger West from the UK/France, moderated by Immanuel Mifsud. The event started off with a short film by Martina Camilleri, and during the event, illustrations by Steve Bonello were shown.

Immanuel Mifsud opened the discussion with a reference to a poem by Maltese poet Marjanu Vella, in which he bemoans how he feels overwhelmed and suffocated by the emerging 6 storey buildings. Mifsud remarked that nowadays we speak of 36+ storey buildings in the making that will dwarf the tallest building in Malta (the 23 floor, 100 metre tall Portomaso Business Tower). Mifsud recalls how even Malta’s national poet, Dun Karm, complained of the suffocation brought about by living in Maltese cities. Mifsud asked: were poets foretelling a future—our present—40 years too early, or have we even surpassed their worst fears?

Roger West kickstarted the discussion by referring to how great English Romantic poets in the late 18th and 19th centuries, such as William Blake and William Wordsworth, have always complained of how the natural environment—and, by extension, something about the human—is being lost due to overdevelopment. Blake, for example, complained of the “dark Satanic Mills” of the Industrial Revolution.

Teodor Reljić remarked, importantly, that the association of all poetry with Romantic poetry is a reductive move which, although pervasive, continues to happen at the detriment of diluting the political edge of poetry. Moreover, conceptions of the environment revered in such poetry remain broadly human-centric in that what is decried is not (just) the degradation of the environment but the loss of what the environment contributes to some humans, for example, elevating the human soul.

This discussion, clearly and importantly, wasn’t some Thoreau-inspired “going back to the basics” hippy rant. It wasn’t about decrying a pure Nature that is being spoiled by the Bad Men, despite Immanuel Mifsud’s exclamation (“Are you trying to tell us that it’s not all bad?”) when the speakers suggested that we should explore new connections that can be made between rural, urban and virtual environments in today’s world. Though neither Reljić nor West sounded keen on the prospect of writing a poem in praise of machines (à la Italian Futurists), they argued that we have to actively engage with contemporary realities.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]It’s said that the human is a social animal, but what remains of this if spaces of sociality are always diminishing?[/beautifulquote]

Both authors touched on an interesting point, which struck me. They emphasised that it’s key not to adopt a unilateral tone of bemoaning environmental degradation. Nostalgia is more or less passé and often seeks to hold on to the past in a patronising and conservative way. Rather than mourn that which is lost, it’s necessary to take stock of the spaces we’re inhabiting and the possibilities tied to them. This is known as psychogeography—a fancy term, I know, which basically refers to how the environment (natural or built) around us affects our mind and behaviour. We’re used to talking of spaces we inhabit virtually in which we can be whoever we want. But it’s just as important to reflect on who we are and who we can be in the spaces that remain inhabitable.

So, when we talk of environmentalism, and when people complain about yet another proposed (or imposed) development, we’re not talking of people complaining that they no longer have places where to organise their Gaia festivals, but of those who are raising awareness on how this continuous development is depriving us of sociality. It’s said that the human is a social animal, but what remains of this if spaces of sociality are always diminishing? What opportunities of sociality, of interacting, of encountering, of feeling are lost as another PA permit is issued?

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Ultimately, when people resist a particular development, it’s an effect of capitalism that they are resisting.[/beautifulquote]

This is why we need to continue to be vigilant and attuned to development realities, rather than snub construction works and its technologies and simply retreat to our hippy cocoon lest we be contaminated by the capitalist machinery. Yes, the C-word. Ultimately, when people resist a particular development, it’s an effect of capitalism that they are resisting. And this is where things become murky. We often hear defeatist laments that the only alternative to capitalism is naïve idealism. This is a disempowering gesture that many (including yours truly) often fall trap to. It’s very easy and tempting to subscribe to the doom and gloom narrative, pour cold water on any attempt of resistance, and despair into the “we are powerless” mantra.

Reference was made to a poem by Victor Fenech in which he appeals to stop the ceaseless theft of free spaces, but ultimately concedes that it’s not about what he wants, but about what they want. One asks: but who are they? Politics and economics, Roger West suggests; capitalist structures and their further hidden networks, banks, insurance companies, tax agents, off-shore companies, their agents and owners. Sounds like something straight out of an Occupy manifesto (or contemporary Malta).

Just as I’m about to get sucked into this familiar (though necessary) chorus, Roger West, sporting a punk look, goes on: We are powerless until we agitate politically. The people will resist. We must use our imagination and encourage questioning in our works. We must contribute to creating a world where creative thinking becomes more of the norm than the exception; where the people question what is given to them, and presented to them as untouchable or unquestionable (economic growth and global capitalism, anyone?)

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Alex Vella Gera: “In what way can a poem stop the Malta Developers Association from getting what they want?”[/beautifulquote]

I’m getting agitated with hope in my seat… until the relentless pessimist (realist?) Alex Vella Gera, most often on point, strikes from the audience: “In what way can a poem stop the Malta Developers Association from getting what they want?” Fair point. Point being that should artists, poets, writers want to really effect change, then the way they should do it is to join efforts that are up in arms, as illustrated by Adrian Grima’s admirable efforts to, with others, organise and mobilise his Pembroke community to stand up to proposed nearby development.

In a country that’s daily bombarded with news on new fuel stations to be built around every corner and new towers; in a country where the only proposed development in the Dwejra area was a, yep, hotel; in a country plagued with short-term non-solutions of chopping down trees; in a country constantly birthing apartment blocks with ever-shrinking apartment dimensions with skyrocketing rent amounts, what is to be done?

Some of us take to the streets to rally; others turn to literature, not just for solace but also to react and to bear witness to realities around us. Reljić, for example, describes how his latest comic book project Mibdul was his way of dealing and responding to the recent Maltese social and environmental realities. After all, as he aptly said, “there’s so much Facebook ranting you can do.”

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Writers can be a voice, and some feel it as their duty to voice it in a variety of tones, and embody the frustrating claustrophobia they feel in this country.[/beautifulquote]

This idea of bearing witness was echoed by the various speakers in this event. No author (or maybe a few) harbours the delusion that they can change the world with their art. But what most agree upon is that writers can be a voice, and some feel it as their duty to voice it in a variety of tones, and embody the frustrating claustrophobia they feel in this country.

Adrian Grima, from the floor, suggested that, as of yet, Maltese literature still has not tried to narrate the feeling of how, alongside diminishing public spaces, our own private space is being taken over, as if it is not a reality that we all face. He suggested that in the next stage of local literature, more people should write about how the sunlight no longer reaches their private space, or how their privacy is being taken away. Or, might I add, how the definition of a private space is transforming into a badly-lit studio apartment, the layout of which you share with tens others in your apartment block, with whose alarm clocks and bathroom noises you wake up in the morning.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]We’re losing spaces where we can be social human beings. It’s not enough to resort to creating such spaces online.[/beautifulquote]

We’re losing spaces where we can be social human beings. It’s not enough to resort to creating such spaces online. Spaces of coming together, of feeling like you inhabit a space or a city together with others is an essential feeling. And an essential political feeling too. We’re not just discussing a couple of uprooted trees here, but inhabitable spaces; we’re debating spaces we can occupy and places rendered out of bounds. We’re talking about the geography of critique; the infrastructure of thought.

This is where literature has a space. Authors can identify such cracks and vocalise them. Not just through scholarly or “high culture” works, but even or especially through popular (or populist) media. Immanuel Mifsud’s “Aqta’ Fjura u Ibni Kamra” (later adapted into “Aqta’ Fjura u Ibni Pompa”) is one such example that resonated with a lot of people.

Yet we clearly acknowledge that we do not live in a world of poets and artists. As important as literature is, it must be connected to other levels of struggle. Art needs thought, and thought needs action. To conclude with a point made at the end of the discussion: Although poems can enlighten activism, good poets don’t necessarily make good activists; and activists might not resort to literature in their efforts. The point is to be aware of where and how the two can illuminate and boost each other.

This discussion served as a taster and teaser of what’s to come in this week’s Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival. This festival has become a staple in the Maltese summer calendar among people seeking to expose themselves to engaged, enraged and inspired literature. If there’s one thing I particularly love about this festival is that it’s an inspiring event. If you want a dose of inspiration and creativity, often with a socio-political edge, in an intellectually colourful space—a space which we need much more of—then you now know where to head down this weekend.

The Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival is on from 23 to 25 August at Fort Manoel. If you want inspiration and engaged literature, then your weekend is sorted.

Leave a Reply