As ancient Greeks once put it, we design the city and the city designs us. Therefore, territorial planning should be treated as a formative tool for helping us become the humans we want to be; any unequal opportunity at this stage will drastically increase the social segregation we are already experiencing.

by Alberto Favaro

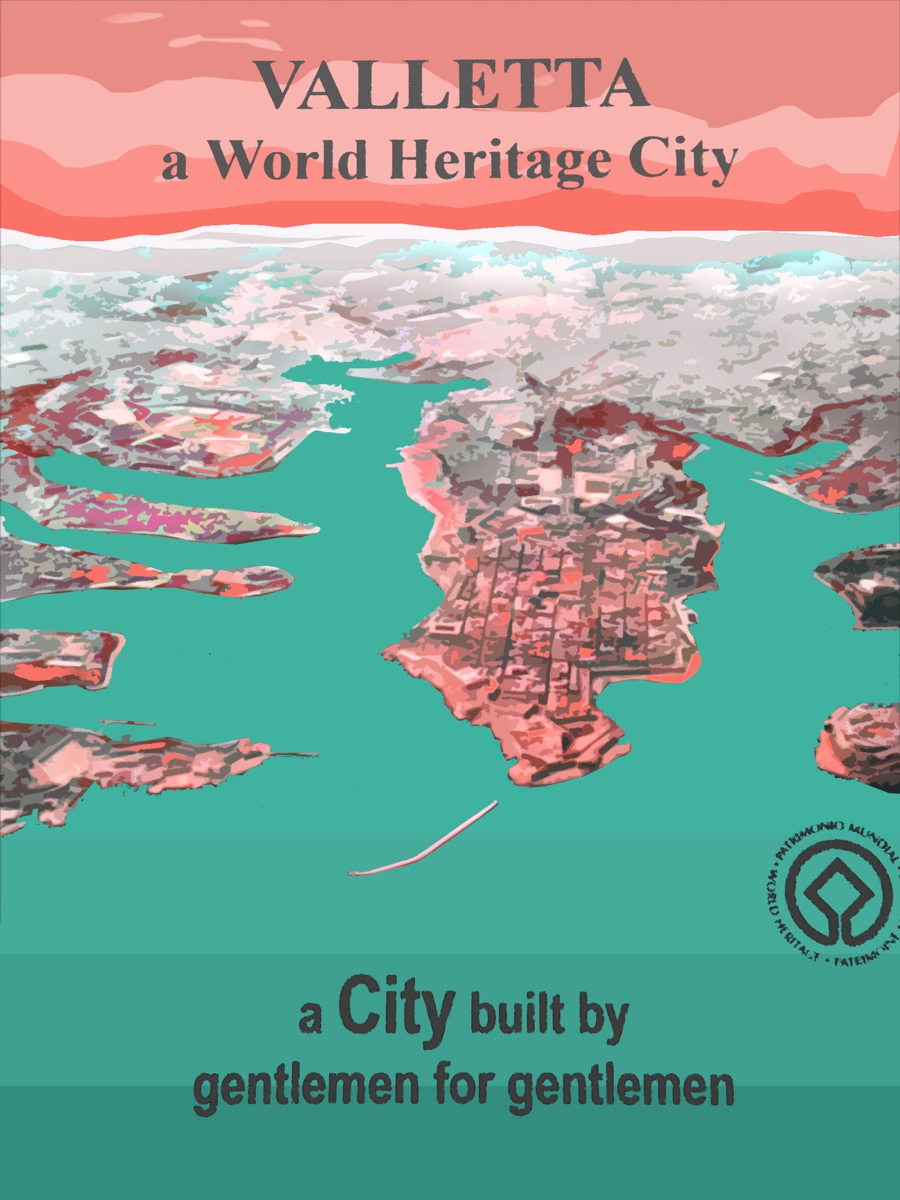

Collage by the author

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hilst talking to an old lady from Sliema several years ago, I was told that despite spending her entire life in Malta, she had never been to some areas of the country among which was the city of Birgu. Having just arrived in Malta and surprised that some people could inhabit a 30km long island and still avoid a big portion of its territory and of its inhabitants, I asked her to elaborate more about her movements around the country. The answer sounded more like a statement than just a logistic choice: “I’ve never been to those areas… I just never cross the line of Marsa. As simple as that.“

Not only did that sentence enlighten me about the severity of segregation taking place in Malta, but it also led me to conclude that somewhere in Marsa there must be an invisible line recognized by a part of the population as an effective partition dividing the two sides of the country. Where one is born, lives or with which of the sides one associates made all the difference to some people.

She was obviously referring to the division between the north and the south of the island—a split that, despite the geographic reference, was more rooted in economic, social and political disparities than geography. Even new expats like me were aware of this division, but before that day, it had never been pointed to me in such a clear and geometrical manner.

Segregated Lives

In the last few years, the social geography of the island has partly changed. The extension of the tourism industry towards the areas previously sidestepped, as well as the growing presence and southward expansion of the rental sector catering for expats, have made the social split of the territory less definite than the original north-south divide used to be. Nevertheless, space continues to be separated. Although Maltese social geography might have changed, the way this geography is defined is still the same, namely through invisible lines.

People just self-dispose towards using spaces that better fit their status, without necessarily connecting to other realities.

This parceling of the Maltese territory takes place through ambiguous space differentiations.

Despite the increasing prominence of societal differences, they are almost never marked with physical devices, but always alluded to, understood and respected rigorously by the different users, locals and newcomers alike. Contrary to what happens in countries where discrepancies are guarded by walls, fences and gates patrolled by high security, here divisions are less evident. People just self-dispose towards using spaces that better fit their status, without necessarily connecting to other realities.

Taking the Portomaso development—one of the most exclusive on the island—as an example, it becomes evident that the privileged estate does not need to intimidate undesirable visitors with gates or fences to preserve its elite status: it is a space “for extraordinary lives”, as advertised, and thus is revered as such.

Mechanisms of Segregation

To understand how this underhand segregation (un-imposed at first glance) takes place, it could be useful to examine the relation between the concepts of ‘public’ and ‘private’ within the process of territorial formation. As much as the social partitioning of space previously mentioned, this basic division is often ambiguous.

Who designates the function of the space?

There are privately owned areas perceived as public just because they have an open access or they provide services to the public. Similarly, there are public areas perceived as private because they are managed by private actors, despite the land or the building being owned by the community. Both scenarios take place on different scales, starting from a small kiosk spreading tables—which defines a specific use and a price for a space previously free for everyone, but still perceived as public by many—to large scale developments, where only prohibitive signs remind us of our role as consumers within a space that doesn’t belong to us at all. These ambivalences often assist private actors in profiting from what we commonly consider public spaces, matched by a weakening of the government’s responsibility.

Since territorial and city formations also develop through dispossessions and appropriations, in order to safeguard equal rights to space for everyone, a strong impartial referee should constantly monitor and mediate these processes.

The expanding role of private actors in the planning of common space defines the criteria for the evaluation of spatial planning.

Any reduction of a government’s role in the planning and maintaining of access to space should alarm us because the significance of territorial planning goes beyond what meets the eye—it sets the very foundation of the socio-economic model. As ancient Greeks once put it, we design the city and the city designs us. In this context, not only does the expanding role of private actors in the planning of common space advance the interests of some at the expense of the community, but much worse, it defines the criteria for the evaluation of spatial planning. In other words, developers’ participation sets the ideological track upon which the government evaluates any option regarding the use of space.

At the core of the adopted model lies the influential private actors’ keen interest in developing the urban fabric: it allows them to absorb over-accumulation of capital and to convert it into assets from which they extract extra value in return. Framed in this way, space is valued only for its relevance within a circular production of capital. It’s evident how an approach to the city that does not comply with this model loses any priority on the agenda. The adopted model presupposes an idea of space and city as financial opportunities rather than a livable place. Although such an approach is expected by developers, it should raise our concerns because the government completely shares this vision.

Valletta: the Costs and Consequences of Regeneration

In this light, some public interventions—at first glance seemingly unrelated to social planning—could instead assume different aims. That’s the case of urban regenerations or ordinary city maintenance: promoted as improvements for everyone, these heterogeneous actions often aim to make specific areas more attractive to those willing to profit from the city.

It is worth examining a specific kind of public intervention which is usually considered unrelated to social segregation—heritage renovation.

Heritage renovation focuses not only on the aesthetic of cities; it also alters their socio-economic geography.

In fact, such public measures, seemingly driven by the need for architectonic preservation, often alter not only the aesthetic of cities, but also their socio-economic geography. Historical city cores happen to be potentially the more profitable within such a model which treats space as an economic resource to be exploited. Hence, it’s not surprising that public heritage renovation is often accompanied by developers’ attention, and its final success is measured according to the amount of investment it will attract.

Valletta could be a typical example of this process: the last decade of the city’s regeneration has been happening under the motto “A City Built by Gentlemen for Gentlemen”. Similar to Portomaso, this elitist slogan reveals a conception of space that goes beyond the purely aesthetic: It underlines the idea that a city regeneration would not be complete unless it ‘renovates’ the social fabric together with the architectonic one. Therefore, the slogan points straight at the lower social classes that have inhabited the city after the war, when the “gentlemen” moved to other areas, treating their presence as indicative of the city’s decay.

On the one hand, the return of the “gentlemen” seems a threatening reference to the gentrification taking place today. On the other hand, this statement simply described a revival of Valletta, but did so by emphasizing the kind of people who should inhabit it, instead of using architectural and urban terms.

This relation between urban heritage and social class reveals a process, unfortunately taken for granted, according to which prominent spaces should be ennobled, not only by restoring them, but by changing function and users, preferably towards more ‘noble’ ones.

Unfortunately, such changes, as for example Is-Suq, are often conceived in line with the maximum revenue these prime sites could generate—and that’s the case of the many valuable public architectures converted into representative venues or cultural facilities. Although they may be nominally public, these spaces are designed to appeal to upper social class, following the logic of ‘relevant locations deserve relevant functions’. This implies that not only could architecture be ennobled or degraded by its users, but the users are ennobled or degraded by the kind of architecture meant for them.

Objects and spaces with which we deal daily from childhood teach us who we are socially and shape us accordingly.

The use of public space and common heritage is therefore an utterly relevant aspect to consider when we seek to analyse the processes underpinning social segregation. As Pasolini claimed, objects and spaces with which we deal daily from childhood teach us who we are socially and shape us accordingly. Education by parents and schools just crystallizes what objects and spaces have already taught us. Therefore, territorial planning should be treated as a formative tool for helping us become the humans we want to be; any unequal opportunity at this stage will drastically increase the social segregation we are already experiencing.

![]()

Accessibility is not merely a physical factor; its facets are also economic, administrative and social. In fact, the combined effort of governments and speculative investors also drives people out of freshly renovated public areas, revealing that such interventions will not be enjoyed by the entire community as claimed. As a matter of fact, newly paved squares and public gardens, when surrounded by private residences and businesses addressed to a specific social class, will be used just by a few regardless of whether these spaces are still called public and have open access.

This ambivalent geography, constructed by the invisible lines which induce social groups to self-exclude themselves from the areas discordant with their status, brings two questions to mind:

Could we call a space public just because it is accessible, even if it only attracts a specific public, while rejecting others?

And could a space still be called public when it becomes a theatre for social segregation, instead of social interaction?

Alberto Favaro is an Italian architect currently residing in Malta. His architectural work has always been accompanied by artistic research, with the intent to question and problematize space. He makes use of different media to express his work such as drawing and printing of imaginary architecture, photography, art installations. His most recent investigations about spaciality of borders were presented in Mdina as an art performance and photographic installation entitled “Geography of Life” as part of Utopian Nights 2018.

Leave a Reply