The perfect, romanticised version of motherhood—the ‘motherhood myth’—needs to be dismantled. Women who are childless by choice are controversial, but women who regret motherhood…? This is the ultimate taboo.

by Liza Caruana-Finkel

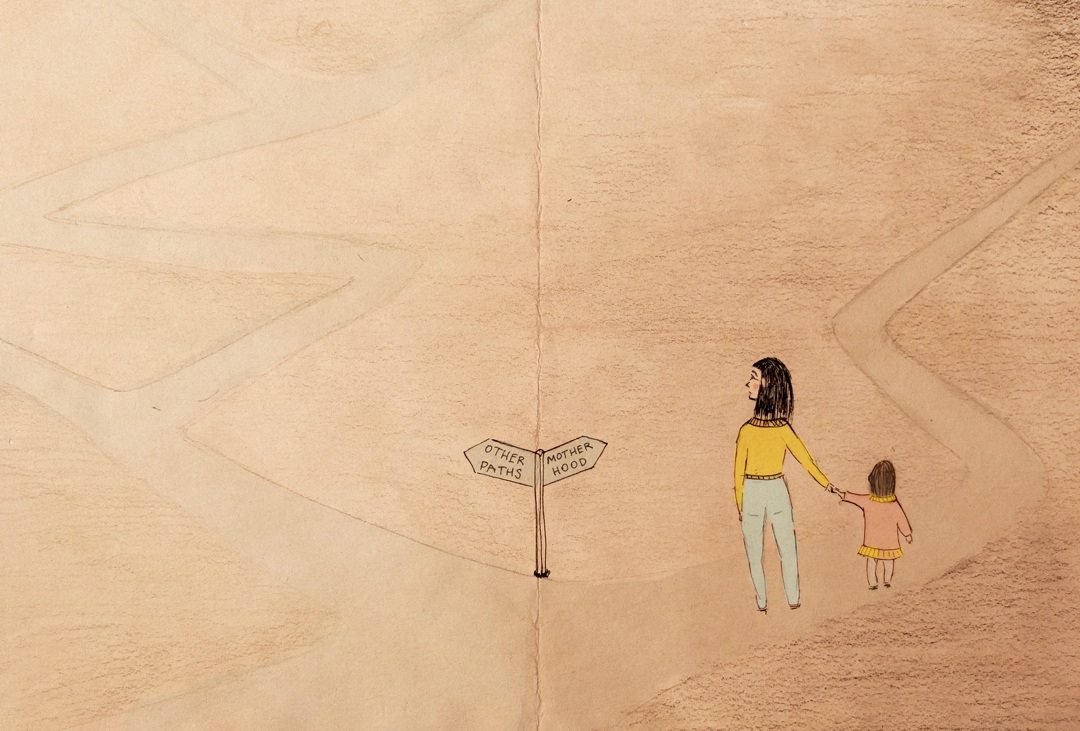

Illustration by Nastia Finkel

‘Regretting motherhood is a dark secret many women hide. But pretending it doesn’t happen, or passing judgment when it does, are insidious ways of diminishing the truth about women’s lives.’

Orna Donath

This article is also available in audio as part of the Isles Aloud Podcast.

![]()

[dropcap]C[/dropcap]ontroversy often surrounds issues related to women—our bodies, our choices, and our lives. We live in a world that idealises motherhood and are continuously told that children are a gift, a joy, and a blessing. Whilst many women are happy being mothers and have a favourable experience of motherhood, this is not the reality for all. The perfect, romanticised version of motherhood—the ‘motherhood myth’—needs to be dismantled. Women who are childless by choice are controversial, but women who regret motherhood…? This is the ultimate taboo.

![]()

We are all subject to society’s ‘feeling rules’, which dictate whether a feeling is appropriate in a given social situation. Abiding by these ‘rules’ usually results in social rewards, including acceptance within society and a certain esteem. ‘Moral emotions’—such as shame, guilt, regret—are also subject to societal norms and regulations. It is expected, for instance, that a person feels regret and remorse upon doing something socially unacceptable, such as committing a crime.

Childless women are told they will inevitably regret their decision at some point in the future.

In arenas other than law or religion, however, we are discouraged from looking into the remnants of our past. We are not allowed to regret our past, yet regret is used to shape our future. Women are told they will inevitably regret their decision at some point in the future, and long for their unborn offspring, if they choose not to become mothers. Unfortunately, this stigma of non-motherhood may cause older non-mothers to experience regret, as they judge their own lives by the culturally accepted measure of a woman’s well-lived life.

What happens when a woman regrets the normative act of motherhood itself?

Motherhood is always marketed as a worthwhile, fulfilling experience, despite any difficulties that may be present, whilst regret of an unfulfilled life is used to thrust women into motherhood. Regret is only seen as a reality with regards to non-motherhood, and never through the act of becoming and being a mother, because mothers are not allowed to feel regret. It is an illicit emotion that is incompatible with society’s ideal and sacred vision of motherhood, which is seen as existing beyond the human realm of regret.

![]()

To regret is to mourn something irretrievably lost; to lament roads not taken. But were other roads readily available? Thinking about our ‘other options’ we realise that some paths are socially blocked. People do not say if you have children, but when you have children. There is a social presumption of a fixed female identity in our pro-natalist society—that of Woman as Mother. The truth is that not all women want to (or can) be mothers, but unfortunately, women are still valued according to our reproductive capacities.

Not all women want (or can) be mothers, but unfortunately, women are still valued according to our reproductive capacities.

Through the advancement of technology in the field of reproduction, techniques such as egg and sperm donation, IVF, and surrogacy are now within reach (especially for more affluent individuals), giving women an array of opportunities to become mothers. As such choices become more readily available, they also evolve into an obligation, a necessity and obsession that society drives women towards. In this way, motherhood becomes even further mythologised as a woman’s true vocation. Infertility can now be ‘overcome’, and so, the sanity of women who do not want to be mothers is questioned. Even their femininity and humaneness are doubted. For a woman to be perceived ‘normal’ and ‘healthy’, the status of motherhood is desirable.

![]()

There is a paradoxical feeling that a woman might experience through childbirth—that in giving birth to a child, she loses her sense of self. That her identity has been irreversibly transformed into that of a mother. As Woman becomes Mother, Woman is eternally lost. Some women have expressed this feeling in writing; this feeling of losing themselves and of struggling against this loss. Author Rachel Cusk explains: ‘My own struggle had been to resist this mechanism. I wanted to—I had to—remain “myself”’; and writer Lola Augustine Brown writes: ‘[W]hat I’m struggling with is that it feels like their amazing life comes at the expense of my own’.

Maternal ambivalence—the coexistence of both love and hate; the simultaneousness of contradictory feelings and thoughts about motherhood—can be a natural aspect of mothering. Some women who feel a sense of ambivalence also see the positive aspect of their motherhood. Ambivalence is not the same as regret. Whereas there is a sense of fruitfulness in maternal ambivalence, regret indicates a fruitless longing for what has been forever lost.

Society has not yet accepted that the difficulties and tensions women face may lead them to regret their motherhood. In fact, there is a blatant disbelief of this regret in relation to motherhood, not only in mainstream media and public discourse, but, ironically and disappointingly, in feminist and sociological literature. The result is that this maternal experience remains unexplored. It remains shrouded in mystery and ignorance. It remains a secret. It remains taboo.

![]()

The expression of love towards one’s own child is the epitome of motherly achievement and ties with society’s idea of ‘good mother’ and ‘moral woman’. Failing to express this motherly love may brand a woman ‘unfeminine’ and an ‘unfit mother’. This could be why regretful mothers seem adamant at professing their love for their children. By doing so, they are reclaiming their right to be seen as moral women, since love is equated with respectable femininity. If they do not express this love, others might assume that regretful mothers hate their children and treat them harmfully.

Regretful mothers are not synonymous with neglectful or substandard parents.

There seems to be a dichotomy between hating and regretting their role as mothers, and the love they feel for their actual children. Regretful mothers do not see the two standpoints as incompatible; there is a distinction based on the target of regret, which is the experience of maternity, and not the children themselves. This, therefore, overturns the binary thinking whereby regretful mothers are neglectful or substandard parents.

![]()

How society approaches a regretful mother is twofold; with disbelief, and with ardent rage.

The problem is that regret is considered a personal failure of the woman to adapt to her life as a mother, meaning that she is simply expected to try harder. This needs to be seen beyond the personal level. The sociopolitical meaning of regretting motherhood needs to be examined, as mothers do not exist outside culture, nor do their regrets. The experience of motherhood, of course, is also deeply linked to how the role of the mother is seen in society and to the matching material conditions of having to fulfil this role. Does motherhood have to mean a loss of self? Would it feel different if fathers as well as other adults and social institutions were more involved in bringing up children?

There has been a rising interest in motherhood regret in the past few years, especially following Orna Donath’s study on the topic. Many media articles detailing women’s personal stories of regret have now been published. Most of the narratives were shared anonymously, but a few spoke publicly. There is also a Facebook page where people can post their stories anonymously. It is, fundamentally, a hub for regretful parents. Such raw, personal accounts of motherhood do not sit too well with most. Although some people applaud the women’s honesty, these stories attract a considerable amount of judgmental and accusatory comments.

There is also a problem in the way motherhood itself is illustrated in the media. Celebrity mothers are often portrayed (or portray themselves) in a perfect, almost supra-human way, and their family life is commonly ‘airbrushed’. Last year, the birth of the most recent British royal baby dominated headlines, with Kate Middleton photographed in heels and make-up hours after giving birth. I am not implying she should not have presented herself in that way, but it does contrast immensely with the reality of childbirth for most women.

![]()

Through women’s personal narratives we are beginning to appreciate that mothers, as human beings, can and do feel regret. Motherhood regret needs to be accepted as a real and valid emotion. It will not cease to exist simply because we deny its existence. When an issue is discussed, it becomes part of mainstream culture, through education, public discourse, understanding, and empathy. If more women felt empowered to speak out about this issue, it would be believed by those who deny it. The more it is discussed and explored, the more women realise that they are not alone in this affliction.

As a woman and a feminist, I believe we must move away from the idea that all women should be mothers; away from religious undertones obliterating bodily autonomy.

As a woman and a feminist, I believe we must move away from the idea that all women should be mothers; away from religious undertones obliterating bodily autonomy. We must release the grip that patriarchy and capitalism have on women, so that we truly are free to decide. We should decide when and how many children we want and who with. Equally, we should be able to choose not to have any children at all, without people thinking us deficient and empty, or pitying us.

As with all life experiences, individual differences in us as human beings, the circumstances we find ourselves in, the choices we face, the privilege we have—all these aspects can contribute to the emotional stance of regret. Motherhood is not experienced similarly by all women in the world; there is no unitary experience of what it is like to be a mother. Regretting motherhood is an essential contemporary debate, a hidden aspect of gendered experience, the epitome of taboo and stigma, the embodiment of secrecy and silencing, and it must be brought to light.

Thank you for this article opening the conversation around women and motherhood. I chose not to mother and 20 years ago, I wrote this song that I performed as part of a half hour, one person theatre show. It’s called Starting out

When a girl starts out,

The circle sings

For her life holds others in her soul

When a girl starts out,

Her mother cries

For her own, sad longing to be free

When a girl starts out,

She cries and sings

For both joy and pain are in her choice

This article is a wonderful tonic for the soul. Within the last week I have had an almost too late stage surgical abortion and my fiance must have known how much this article would help remind me of some of my reasons for choosing No when he shared it as part of his public support of my choice. I cannot be more certain without actually going through with it and actually experiencing it that I would be a regretful mother myself if fate had turned out differently, if it HAD been too late. I am being public about my abortion as part of my feminism for the sake of others in similar situations and with the exception of one faceless private account on instagram all comments have been supportive, but I was ready for an onslaught of judgement and have been pleasantly surprised. This article is fascinating because it looks into what I would have been dealing with on the flip side and shows how for me it really was the lesser evil. It reassures me that the regret element is truly a valid feeling and is applicable to more than just my version of events, i don’t have to regret the termination because regret for not terminating is just as real and until things improve, the judgements for that are worse. My heart truly goes out to the women facing that struggle X

Thank you for this article, it places the woman at the very centre rather than on the periphery of the discussion.