Suffering seems to be an obligatory justification to enter Europe. In a fairer and more balanced system, economic migrants would have not had to take a perilous journey just to find work. But if trauma is the expectation, they get traumatised, too.

by Daiva Repečkaitė

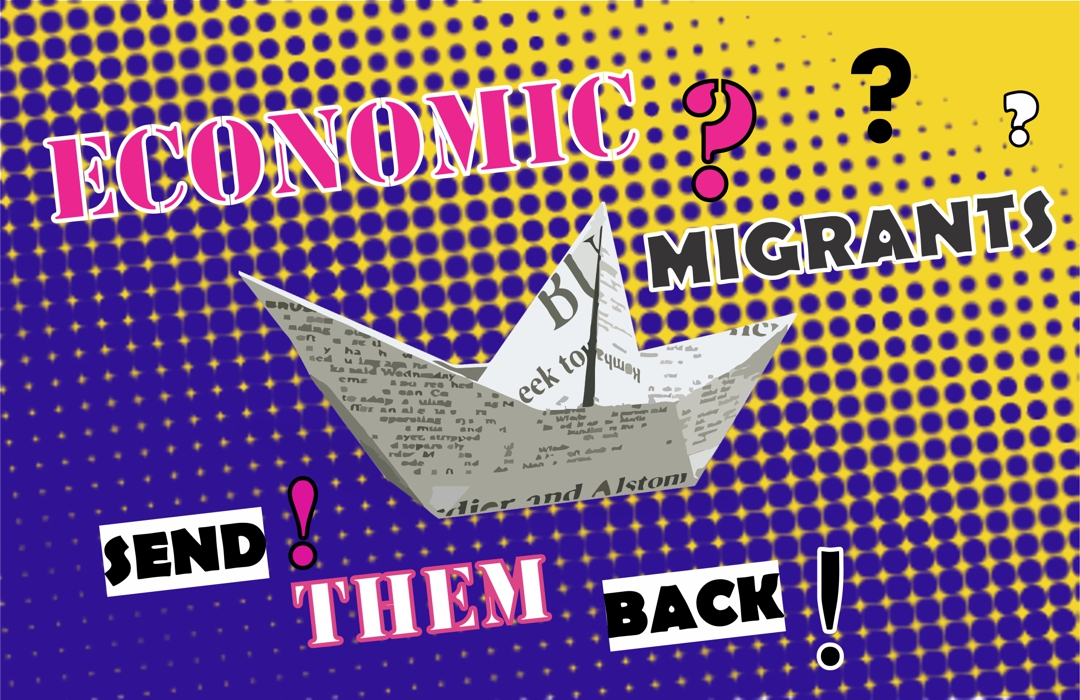

Collage by Isles of the Left

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]orty-four Bangladeshi nationals will be repatriated, the Prime Minister announced outlining the deal to share rescued individuals among several countries. After weeks at sea, with Italy and Malta refusing a safe port to NGO-run rescue ships Sea Watch 3 and Professor Albecht Penckt, 49 individuals from the most recent rescue mission, plus another 249 rescued previously have been sorted, literally and metaphorically.

We do not know yet how many among the others will be rejected and deported from the countries that agreed to process their applications, but the verdict for the 44 Bangladeshis is automatic, announced before the last ship disembarked. They are non-refugees.

Malta’s labour market has been voraciously drawing workers from India, Pakistan, the Philippines and elsewhere. And yet, 44 Bangladeshis who spent days at sea will be repatriated.

The number of destinations available for Bangladeshi migrants seems to be constantly shrinking. India has announced a crackdown on Bangladeshi migration. Gulf Countries are restricting migration and enacting preference regimes for their nationals. According to Migration Policy Institute, citizens of the country, still heavily dependent on remittances, cannot obtain visas or work permits without exploitative intermediaries.

To pay the fees, according to the International Organization for Migration, Bangladeshis resort to family savings or debt. Along the way, 98% spent at least a year in Libya and 63% told IOM that they had been held in a closed place against their will. It cost them between 1,000 and 2,000 USD to leave Libya by sea. Your T-shirt, most likely made in Bangladesh, has by far more freedom to travel the world than the workers who produced it.

Suffering as the Ultimate Justification of Entry

A refugee, in legal terms, is a person fleeing a well-founded fear of persecution. “In the first place, we don’t like to be called “refugees.” […] We did our best to prove to other people that we were just ordinary immigrants. We declared that we had departed of our own free will to countries of our choice, and we denied that our situation had anything to do with “so-called Jewish problems”,” philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote in “We refugees” in 1943.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]It is now the refugee status that makes a person who lacks a privileged background worthy of entering Fortress Europe.[/beautifulquote]

It is striking to observe how diametrically opposite the public discourse on refugee-ness is in Europe today—and how similar at the core it still is to Arendt’s time. Refugees are held in opposition to economic migrants, but in popular discourse, as well as in legal terms, it is now the refugee status that makes a person who lacks a privileged background worthy of entering Fortress Europe. Once they obtain this status, however, they are expected to be ‘productive’ and ‘contribute’ immediately, but that is a subject of another essay.

The popular credibility of asylum systems is judged depending on their capacity to sort applicants for asylum and send the non-refugees back to where they came from.

To counter the doubts regarding the share of ‘deserving’ ones among applicants, many sympathetic well-wishers broadcast the gory details of their journey to the general public. Suffering, as already outlined by Mina Tolu, becomes an obligatory justification to enter Europe. The sympathetic narratives that combine these contradictory expectations are understandable, but they solidify the worthiness imperative, and must be critically reassessed.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Asylum seekers owe their face, their story—and their trauma—to the general public in order to be pitied and accepted.[/beautifulquote]

During her talk at the University of Malta in 2017, anthropologist Barbara Sorgoni pointed out that personal openness and credibility have become implicit demands imposed on asylum seekers. Social workers and volunteers at some Italian reception centres expect them to generously share stories of their trauma. Some centres have made group therapy compulsory, withholding pocket money if asylum seekers do not cooperate, and wrongly creating an impression that credibility in social settings matters in the deliberation of their asylum case.

Looking at many sympathetic storytelling projects that have abounded since 2015, it is also easy to get the impression that asylum seekers owe their face, their story—and their trauma—to the general public in order to be pitied and accepted.

Economic Migrants Suffer, Too

Perhaps the crudest example is a published diary of Lithuanian photographer Vidmantas Balkūnas, who proudly admitted disrespecting the migrants’ right to refuse close-ups along the Balkan route: “I’m well aware that I’m at an advantage—I want to take a photo, and you want to get to Germany. If you raise your fist or make some fuss, you may have to forget the paradise of your dreams. So, covering themselves and grumbling like suspects in court, they reach the Croatian border.”

Hostile photographers aside, even well-intentioned volunteers, photographers, journalists, theater groups and others have hurried to harvest stories of trauma, adding to the hard emotional labour expected of asylum seekers.

But if trauma is the expectation, economic migrants get traumatised, too. With or without NGO rescue, the journey to Europe is so risky and perilous that it damages all migrants. There are exceptions in the laws, where deportation can be halted if a person is mentally or otherwise vulnerable, and it is rather surprising that the announcement was made about automatic deportation of the 44 Bangladeshis without making any vulnerability assessment. Their country does not pass the threat assessment by asylum authorities, but their individual journey from that country might.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]In a fairer and more balanced system, people would have not had to take a perilous journey just to find work.[/beautifulquote]

With increasing awareness of mental health and improved assessment, people should eventually be able to make their case and prove that after the dangers in Libya, abuse and weeks at sea, they deserve a respite and treatment of any health conditions they have developed. In a fairer and more balanced system, they would have not had to take this journey just to find work. Having realised how expensive and exhausting it is for everyone involved to have Balkan migrants try their chances at asylum, be housed, go through appeals and be deported, Germany has developed a work visa scheme.

In the absence of labour migration schemes, attempting asylum is currently the best bet for many residents of the poorest regions, especially in Africa, at becoming ‘guest-workers’.

While inter-governmental agreements and networks of employment agencies facilitate labour migration from countries like the Philippines, there are no comparable schemes for Africa. To access the system, one must first become vulnerable. So a perfectly healthy job-seeker from a relatively safe but poor country is abused and traumatised along the way, until he or she reaches the shores of Europe broken and exhausted. This does not make sense morally nor economically, but this is the logical result of a system that is geared at sorting ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ asylum-seekers and has few fair and accessible pathways to work.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Since there are no labour migration schemes for Africa, to access the system, one must first become vulnerable.[/beautifulquote]

Speaking at a forum in Alpbach in August, German Constitutional Court judge and legal scholar Susanne Baer argued for a post-categorical thinking in legal discourse. Our starting point should be a person who is seeking justice, she argued, and we can then look at the legal instruments and see what is available for that person—including social and economic rights, which are human rights as well.

Individuals come to Europe escaping political, social, legal and environmental injustice. This is a person persecuted for their activism. This is a person fleeing war. And this one is fleeing an environmental disaster. Are our systems robust enough to use this quest for justice as a starting point to build a fairer migration system?

Leave a Reply