The sea has always been the major force that shaped history of Malta. Today, the seafront as a public space seems to be the only resource element that somehow managed to survive, but for how long will it prevail?

by Kristina Borg

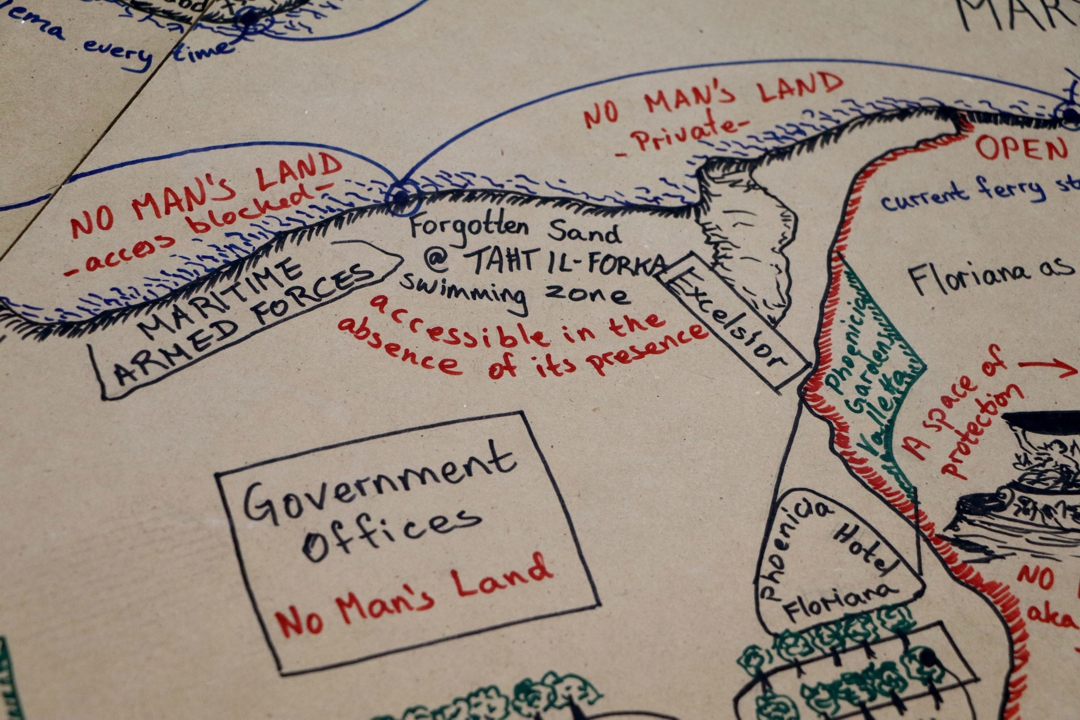

Image: Marker drawing on found platform (exhibited at St Elmo Examination Centre as part of Dal-Baħar Madwarha collective exhibition, 2018), by the author.

I am an ancient being, that ancient being that has always shaped the island’s story. I know everything and I saw everything; I shall always know everything and I shall always see everything. I’m so wide that the meaning escapes you, but if you’re patient and try to listen carefully you can find that meaning again.

– Excerpt from the performative narrative No Man’s Land, June 2018 –

This article is also available in audio as part of the Isles Aloud Podcast.

[dropcap]I [/dropcap]began reflecting on what it means to be an islander during the years I spent living abroad. While living in a metropolitan inland city, I immensely missed the sense of seeing forever, over and beyond the distant horizon of our sea. Being able to look at the horizon has always given me a feeling of calmness and a sense of curiosity about what lies beyond.

Returning back to Malta, I realised that this should not be taken for granted. The island has been built up to such an extent that a glimpse of the distant horizon, or smelling and tasting the salty spray, is no longer accessible, except for being by the shore.

The sea has always been the major force that shaped history of our country. It brought food, goods, storms, visitors, good and bad news.

Last year, I had the opportunity to reflect more on this whilst researching for my project No Man’s Land, which culminated in a number of context-specific, performative boat trips around Marsamxett and Grand Harbour.

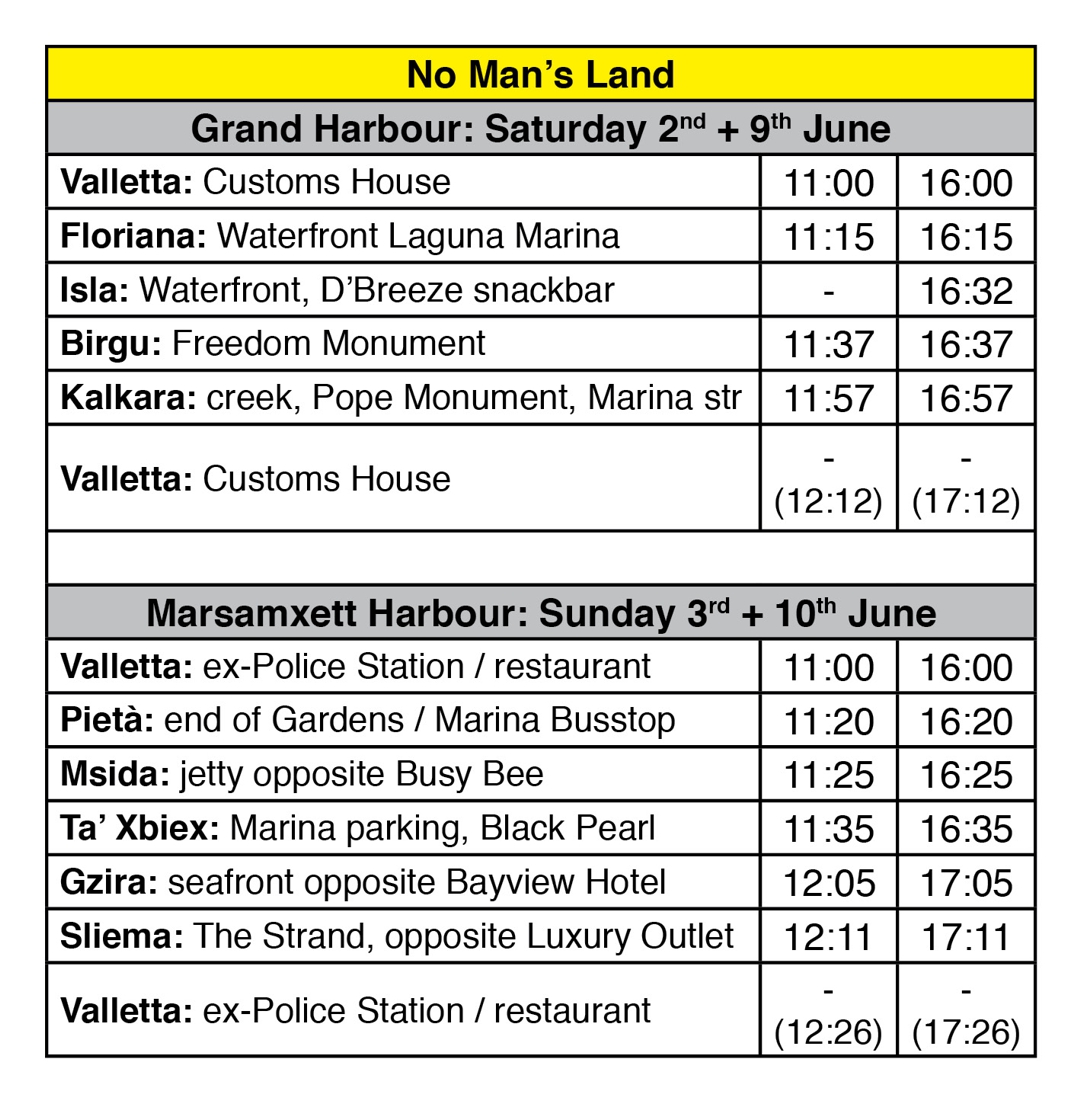

The project drew on a series of conversations with the locals of the harbour areas. It aimed to discover how the invisible borders between localities are rendered visible. It also explored the spaces in-between, at times contested as a no man’s land. Additionally, No Man’s Land piloted an alternative mode of transport: an electric-powered boat offering a circular route increasing the pick-up/drop-off points around both harbours. The connecting theme of the diverse aspects of the project was to narrate the locals’ relationship with the sea.

Here is what I learnt about the sea through the stories I collected.

A Sea That Connects

The locals of the harbours’ area believe that the connective potential of the sea is currently severely overlooked. It comes as no surprise that the better use of the ferry services could be one of the alternatives to overcome the day-to-day traffic crisis. Whilst replacing the present day ferry boats with sustainable electric or solar powered boats would be an entirely new initiative, extending the ferry route network is more of a revival of the past routes of il-lanċa.

Some of us might remember the Valletta-Senglea-Vittoriosa route, especially in the ‘50s and ‘60s. A Vittoriosa local told me how common it was to take il-lanċa to carry bulky cargo, such as a sewing machine or a bicycle bought from Valletta.

In the past, Marsamxett harbour used to offer more in terms of mobility than today’s Valletta-Sliema route: from 1886 to 1922 the ferry services used to operate to Msida too, having its berthing place close to the parish church. Not many locals may recall this, apart from those few who remember the skeleton of the landing place or have possibly seen it in a photo.

A Sea That Feeds

For those inhabiting the central harbour areas of the island, the sea has always been part and parcel of their daily life.

Locals remember how Pinto Wharf (today’s Valletta Waterfront) served their daily needs. Down Crucifix Hill, docked at the waterfront, boats from Gozo used to import livestock and a rich variety of agricultural produce. This was the public space, the hub for the daily chitter-chatter where people discussed news, shared joys and worries. It connected people and spaces within and beyond our shores—an archaic version of our present online network, perhaps?

The sea was a busy road. Transportation around the area of the Three Cities and Kalkara relied on the hardworking boatmen (il-barklori) who, rain or shine, brought in passengers from the ships outside the harbour to the shore. Kalkara, together with Gżira, was also renowned for the traditional boatbuilding (fregatini).

People from the inner parts of Msida, now in their retirement, shared stories about how essential fishing was for their families—either for domestic consumption or as a source of income. They recall the fishing nets spread flat on the ground, in front of the parish church, in preparation for cleaning or repairing. Scenes like these might seem alien to most of us, but we can picture how the proximity of the sea alleviated poverty and allowed families to make ends meet.

A Sea That Nurtures

I must not leave out the playful element of the sea. Many of the people I interviewed for the project remember playing by the sea as kids, exploring the harbour until late at night and rowing their DIY boats.

A man from Gżira recounted when as a child, together with his friend, he bought his first raft. Although they could not afford it, the sea offered a solution. Every morning they used to dive for glass bottles, thrown away and dumped on the seabed, and in the evening they returned them at the grocery store, earning a few cents for their glass recycling endeavour. Little by little, they managed to save enough money to buy a raft, and enjoyed rowing out to Sliema.

The sea was so child-friendly that it was common for children from Gżira to swim from Manoel Island to Valletta and back.

The sea was so child-friendly that it was common for children from Gżira to swim from Manoel Island to Valletta and back, or in the opposite direction for those who lived in Valletta. On the last day of the scholastic year, Msida children used to swim back home from their school—situated within the confines of today’s Pietà—to the creek.

The sea was also indispensable when it came to catering for basic hygiene needs. In the ‘60s, when water supply for domestic use was limited, the sea immediately provided people living by the shore with a service: buckets of seawater were used to flush toilets. The sea has always provided us with everything we needed—community, transport, food and fun.

A Sea That Excludes?

And now, what do we have left of all this?

The seafront as a public space and meeting point seems to be the only resource element that somehow managed to survive until today, but for how long will it prevail?

Unfortunately, some parts of the Grand Harbour—Marsa and neighbouring Paola—have become derelict to the degree that the locals describe them as a ship graveyard. The direct link with the sea has been cut off by several infrastructural projects that robbed us of the access to the coast and a closer relationship with the sea. I’ve learnt that the locals do not even feel part of the Grand Harbour anymore.

By now, we have become used to the private investor who takes over, molds the rocks into concrete, closes off everything behind a gate, and impedes our daily walk.

I was particularly struck by the situation in Floriana where an extensive part of the coast has either been privatised or taken over for administrative and entertainment functions, thus offering no specific benefits to the locals. Despite overlooking both the Grand Harbour and the Marsamxett Harbour, the accessibility to the sea has been practically blocked by a number of ventures.

Who can ever imagine that on the spot of Haywharf club and Hotel Excelsior there once was a sandy beach? Today’s very small area of the so-called swimming zone is, in the words of a local, “accessible in the absence of its presence”.

Who is benefitting from all these private ventures?

Laguna Marina at the Valletta Waterfront describes itself as “an exclusive, boutique yacht marina on the Valletta waterfront and the only marina in Malta to offer an ‘all inclusive’ option to its clients.” I dare say, inclusive in its exclusivity! Since when did the sea become exclusive or selective? How does this cater for the common good?

The list goes on forever. Some of the examples include Marina di Valletta in Pietà, and the Manoel Island and lido developments in Gżira.

Negligence of the tangible relationship between the people and their physical environment results in hostile urban planning.

Negligence of the tangible relationship between the people and their physical environment results in hostile urban planning. Our open public space is being eroded not only by the private sector, but by our public authorities as well. Locals from Msida, Gżira, and Kalkara recall their childhood days when land at the seafront was reclaimed to widen the road. They describe the negative impact this has left on the sea and how its behaviour changed. As though it were a mythical creature, the sea started rebelling, crushing the shore, whereas before it had more space to vent out its energy and glide in softly, calmly.

Today, in 2019, it seems that we haven’t learnt the lesson. The Minister for the Environment Josè Herrera stated that “land reclamation at sea is the most long-term sustainable solution” to deal with the construction waste crisis. How can we convince the authorities that the impact of this proposal will be irreversible and drastic not only on the nature—the coast, the sea and its ecosystem—but also on the wellbeing and lives of the people?

Is this what we mean by progress?

![]()

So yes, my waves have saved you across generations, and I can help you bridge the bastions on either side of the harbour and open up to more areas, but remember that whatever you do has an effect on my water quality. … You cannot expect any longer the bastions to save you from the harm you’re doing to your island. And I’m afraid I can’t save you either, it’s your turn to take the helm! It’s your turn now to save me!

– Excerpt from the performative narrative No Man’s Land, June 2018 –

Kristina Borg is a visual artist and an art educator. Her research strives to create projects involving experimental processes through which she seeks to relate and enter into direct dialogue with the community and/or the place. Her works have been exhibited in Malta, Milan, Salerno, Perugia, Munich, Dusseldorf, Vienna, Vorarlberg, Leeuwarden, Haarlem and Brussels.

![]()

No Man’s Land formed part of the exhibition Dal-Baħar Madwarha, curated by Maren Richter and commissioned by Valletta 2018-European Capital of Culture.

Leave a Reply