It was through their ‘tolerance’ of Carnival and other Catholic rituals, that the British aimed to freeze the flow of time in order to actively prevent social change from taking place in Malta.

by David Edward Zammit

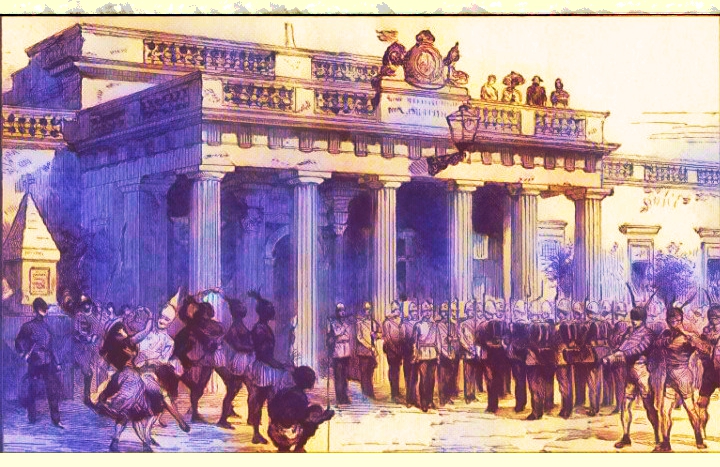

Image: Sketches of Life at Malta. Carnival Time: Mummers Going Through the Ceremony of a Burial Without Coffin (1882), colorised

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 1822, the ‘Little Prisoner’, a Malta-based children’s novel written by an anonymous author was published in London. Claiming to describe ‘a visit to the island of Malta founded on fact’, it contains an intriguing account of a misadventure which occurred to the protagonist’s father, a British army colonel. While returning to his home in Valletta during Carnival time, he was suddenly surrounded by a group of masked Maltese revellers. His daughter, who was watching from the balcony, noticed that they had caught hold of him:

Soon after, Caroline exclaimed: “Oh! mamma, mamma, what will become of papa? only look, a great number of people have seized him: what are they going to do?”

“Your papa is indeed fairly caught, my dear,” said Mrs. Melville, “but they will not hurt him much; they are only teasing him, as they do every one who appears in the street unmasked. The governor has given orders that no British officer or soldier shall appear masked during the carnival, and therefore I suppose the inhabitants like to tease them, now they have an opportunity. Your father hoped to have escaped by coming down a back street.” Caroline continued watching.”

This introduces us to the world of early British Malta: where British officers lived next door to Maltese civilians in Valletta; while their children utilised the neutral viewing platform of a typical Maltese balcony to observe the crowds below. This was also a world where British soldiers were expected, by gubernatorial fiat, to expose their uncovered faces to the taunts of native ‘maskerati’. The teasing could get quite physical:

The group of dancers placed the colonel in the midst of the circle they formed, and began dancing round him: every turn, one of them broke from the circle, and danced up to him, slapping his cheeks smartly with both hands, and then danced back to her place, which was repeated until every one had had this gratification. The colonel took it all with good-humour, which pleased them so much, that when the ceremony was ended, they protected him against all other parties, who would otherwise have attacked him, and thus he was guarded to his own door.”

This tactical use of the playful dance in order to turn the tables on the strangely submissive British colonel reveals how Carnival festivities could be wielded as a political ‘weapon of the weak’ in the hands of Maltese natives to challenge colonial hierarchies. Powerful resentments are here being expressed in a violent yet controlled manner through admonitory slaps which cunningly utilise the anonymity of a masked dance to dare to lay rough hands upon the very face of colonial power.

However my focus here is on the Colonel’s passive response to these slaps. What can it tell us about British attitudes to Maltese religious rituals in the early colonial period? In order to understand it more, let us follow the Colonel home where his son asks an important question:

The children all ran to meet him, desirous to know if we were hurt. “No, my dears,” said he, “I am not much hurt, though I confess my face burns a little. These ladies’ hands are not very soft; they are all, I believe, men dressed up like ladies, for no women’s hands could ever be so hard and rough.”—“Why did you not fight them, papa, with your sword?” said Frederic: “if I had been you, I would soon have knocked them all away.”

The Colonel’s reply touches upon the basis of British ‘soft power’ in early colonial Malta:

“Oh! what a brave fellow you are,” answered his father, “but let me tell you, my boy, you would have been very foolish, and even wicked, to have drawn your sword on such an occasion. These poor people only wanted to have a little fun, and to punish me for not complying with the customs of their country; and though they annoyed me a little, they had not the slightest intention of doing me any serious injury. A soldier, Frederic, does not deserve to wear a sword, who cannot command his temper on much more trying occasions than this: besides, it is the act of a coward to draw a sword on those who are unarmed, and, consequently, not on equal terms with you.”

By referring to the foolishness of failing to ‘comply with the customs of the country’ the Colonel was indirectly alluding to the first proclamation of British Commissioner Cameron some twenty years previously on the 15th July 1801, which started by stating that: ‘His (Britannic) Majesty grants you full protection and the enjoyment of all your dearest rights. He will protect your Churches, your Holy Religion, your Persons and your Property’.

Throughout the British colonial period, this Proclamation was regarded as having a foundational importance. It established British rule upon a basis which stressed respect for the religious customs of the Maltese people as part of a bargain through which, in exchange, the British could be granted access to and control over the fortifications of the Knights and in a sense ‘step into their shoes’ by acquiring sovereignty also over the Maltese people. In the words of the marble tablet which Governor Maitland affixed to the ‘Main Guard’ building opposite the Palace in Valletta, this bargain was to be based not so much on British military victory over Malta but because the ‘Voice of Europe and the Love of the Maltese had granted it to them.’

![]()

While often described as being merely a pragmatic acceptance of Maltese Catholicism designed to avert native hostility to the Protestant British, I think the British support of Maltese Catholic rituals was broader and more enthusiastic than required by mere tolerance. It is interesting for example, to note that the British Governors early on adopted the custom of hosting an annual Carnival Ball in the Palace, to which they would invite the Maltese nobility. This traveller’s * account comments:

The upper classes of the Maltese are, I am told, reserved and dignified, and, except on three occasions during the year, will not mix in English society, nor will they permit their conquerors to make acquaintance with them. The occasions to which I allude are the three public balls given at the palace, on Christmas day, the last day of the carnival, and on the Queen’s birthday. To these three balls the Maltese vouchsafe to come.”

Moreover the British embrace of Catholic ceremonial extended to other rituals besides Carnival.

Soldiers were ordered to fire a salute during important religious festas and they were expected to show respect to the Viaticum procession. This support of Catholic ritual by Protestant British governors drew an incredulous response from lower-ranking colonial officials, sailors and soldiers. As a writer in the Parliamentary Review of 1833 observed:

In Malta, we allow not only the utmost latitude to the profession of Catholicism, but we foster its splendid and pageant-like ceremonials. Nay further, we have compelled (most injudiciously be it admitted) English Protestant soldiers to perform military honours to the procession of the Consecrated Host.“

This ’fostering’ of Catholic ‘pageant-like ceremonials’ by British Protestants can perhaps best be understood in the light of the colonial ‘strategy of continuity’ developed by Sir Alexander Ball, the first British ‘Civil Commissioner’ for Malta. This strategy was: ‘designed to win popularity with the inhabitants’ and it aimed: ‘to continue operation of all the institutions of the government of the Order of St John’. Yet, as Michael Kooy observes, this policy: ‘had unintended consequences. The Knights of St John had reserved to themselves, and notably to the Grand Master, sweeping despotic powers. Ball, in agreeing to preserve local constitutional arrangements, found he had inherited the powers of a feudal lord.’

![]()

As a political strategy, the assertion of political and institutional continuity with the Knights goes much further than simply respecting the customs of the Maltese.

In fact it provided the direct means through which British governance could legitimise its authority as successor to the Knights; meaning firstly that it succeeded to the property and sovereign control which were ‘part of the package’ of this Knightly inheritance. Moreover and even more significantly, it provided an agenda for governance which allowed the British authorities to refuse to consider any progressive Maltese movement aiming at political reform; on the grounds that it would be betraying its contract with the Maltese people if it were to accept any institutional change whatsoever.

The illustration accompanying this article is taken from a Victorian magazine and clearly brings out the way the British wanted the Carnival in Malta to be experienced and remembered. On the left are Maltese natives; whose aboriginality is strikingly evoked by portraying carnival mummers who have blackened their skin and dressed up as American Indians. On the right, standing to attention before the neo-classical portico of the ‘Main Guard’ and directly under Maitland’s memorial tablet, are parading British soldiers dressed in their full military regalia. British sovereignty is also reflected by the lion and the unicorn and two high ranking British officials and their wives, who are standing next to it and ‘looking down’ upon the scene beneath. The colourful and disorderly ceremonies of the natives are contained within a frame of British military structure and there is an unbridgeable spatial gulf between the natives and the soldiers.

The patience of the Colonel can now be understood as profoundly strategic.

It was through their ‘tolerance’ of Carnival and other Catholic rituals, that the British aimed to freeze the flow of time in order to actively prevent social change from taking place in Malta. Like the spectacular ceremonies of colonial India recently evoked by Jeremy Paxman, British colonial endorsement of Maltese Catholic ritual was the result of a far from innocent political calculus. Contemporary complaints that Maltese Catholicism is more concerned with empty ceremonies than with social change and that many Maltese people appear to be living in ‘a world of their own’ may owe a lot to this strategy.

![]()

* Anonymous, 1858, Wanderings in the Land of Ham by a Daughter of Japhet, London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, p.244

Dr. David Zammit is Head of Department of Civil Law at the University of Malta. His interests include Anthropology of Law, Tort Law, Law and Narrative, Administration of Justice, Anthropology of the Mediterranean.

![]()

For further discussion on the Maltese Carnival under the British, read ‘Carnival and Power – Play and Politics in a Crown Colony‘ by Vicki Ann Cremona.

Leave a Reply