Malta’s language question has been a subject of an ongoing debate for over a century. Today, our native tongue might be appropriated for some sinister purposes. How can we support the use of the Maltese language while not letting it become a tool of xenophobia and racial exclusion?

by Michael Grech

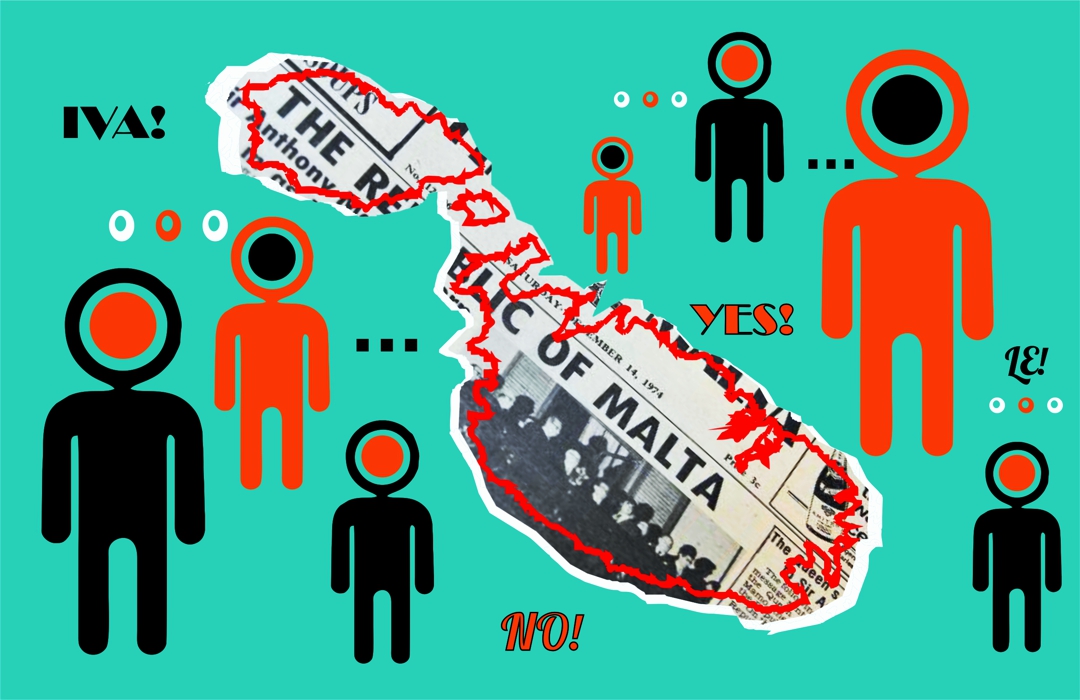

Illustration by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]L[/dropcap]anguage shapes our perceptions of the world. There is a definite connection between the languages used and the way different social groups relate to each other both within a society and on a global scale. Figures of speech, analogies and metaphors may reflect, reinforce and possibly challenge or change these power relations. Feminists, for instance, have frequently pointed out how certain expressions emphasize patriarchy, suggesting various linguistic strategies to subvert its grip.

The link between language and power relations is not limited to the use of specific terminology. Different languages also play a significant role in national and other geopolitics. Consider that the current status of English as a language of ‘international’ communication is an outcome of the former British Empire’s fortunes first, and of US hegemony later. Divisions within societies are frequently cemented by people speaking different variants of the national tongue or different languages. The aristocracy in Tsarist Russia, for example, spoke French.

Language Politics Prior to World War II: Italian as the Language of the Elite

In Malta, language and power relations have gone hand in hand, too: national languages frequently reflected class divides since different social strata had different linguistic preferences.

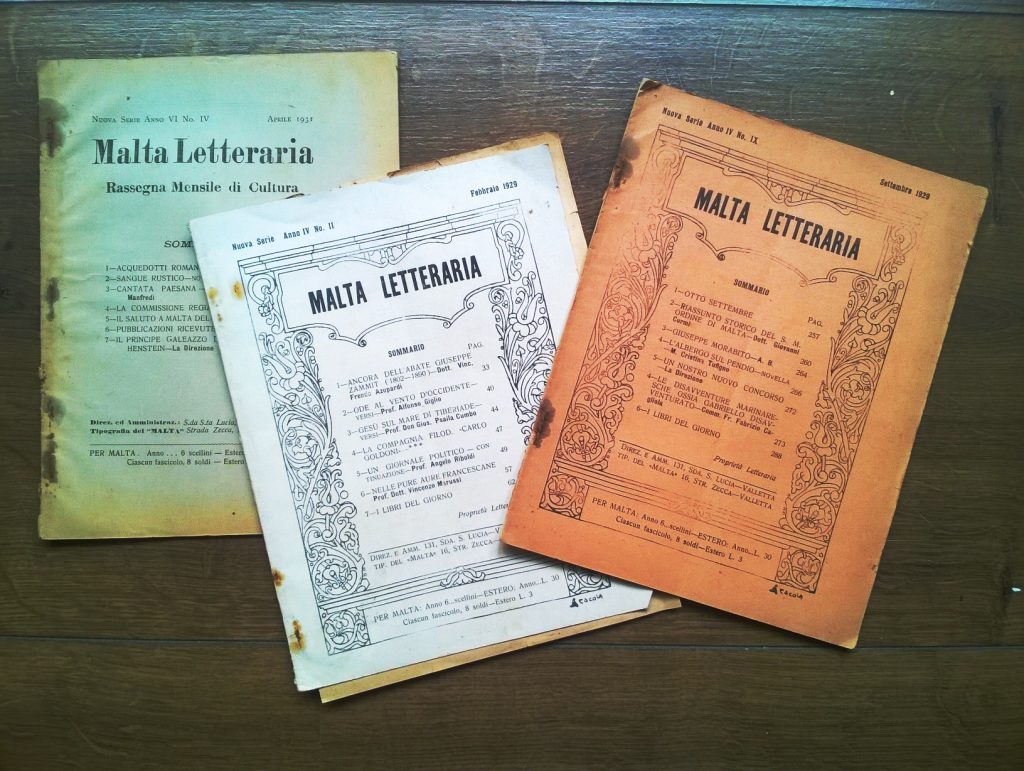

Prior to World War II, the Maltese upper classes and privileged groups such as the nobility, clergy, lawyers, notaries and doctors generally considered Italian to be their language. The rest of the population, in most cases, spoke various dialects of Maltese.

However, there were exceptions. The Maltese language would probably not have evolved literarily had it not been for some members of the upper classes and particularly the clergy—especially those coming from a rural or lower class background—who retained a love of the language they spoke at home despite their Italianate education. Dun Karm was arguably the prime example. Similarly, there were people who did not belong to the upper classes but who were fluent in Italian. Yet the overall situation was very similar to that in most of the Italian peninsula, where the elite generally spoke Florentine while the rest of the population communicated in other dialects.

Prior to World War II, the Maltese upper classes and privileged groups spoke Italian while the rest of the population, in most cases, spoke various dialects of Maltese.

At the same time, there were other developments. Being a British colony, Malta was involved in the goings-on of the most powerful Empire of its day. Inevitably, the economy and the day to day existence of a number of people, especially in the Three Cities, became intertwined with the British.

Not only did the dockyard undergo gigantic changes to meet the needs of the British fleet, but a segment of the local bourgeoisie also began forging closer commercial, cultural and working ties with British individuals and institutions. Just as the working class Maltese employed at the dockyard, they found the use of English much more congenial to their needs, and generally supported attempts by British rulers to advance the use of English alongside the Maltese language.

However, many members of Maltese society (especially those belonging to the classes that were traditionally privileged) largely opposed such attempts in the name of tradition and national identity. The opposition between the English- and Maltese-speaking bourgeoisie on the one side and Italophiles on the other contributed to the birth of the first political parties. It is worth noting, though, that during late 19th and early 20th centuries:

- English was not the language of the elite, but only of part of it.

- The English and the Maltese languages were not considered antithetical to one another. Many championed both.

- Supporting the two languages was ‘progressive’ since it allowed challenging the authority of the classes that had been ruling the Maltese islands for centuries.

World War II. Demise of Italian and a Growing Influence of English

World War II significantly altered language politics in Malta. Supporting the Italian language was no longer popular, except for some Romantics like Enrico Mizzi and Vincenzo Maria Pellegrini, who generally limited their support to literary ventures. The Nationalist Party transformed its support for the Italian language into a defense of the supposedly Latin character of Maltese culture.

Another factor which changed the political scenario following World War II was greater political consciousness developing in the lowest echelons of society, especially expectations as to the duty of the state to cater for their needs and address poverty. This led to a stronger political organization of the working classes. The General Workers Union was formed in 1943, and Boffa’s Labour Party, which had been the third and smallest party on the islands before the war, won the first post-war election by a landslide.

Another factor which changed the political scenario following World War II was greater political consciousness developing in the lowest echelons of society.

Increasing working class consciousness and organization alarmed the culturally and economically dominant elites. By the beginning of the 1970s, the affluent had largely gravitated towards the Nationalist Party, which—under Eddie Fenech Adami—became a Christian Democratic mass party. Though the majority of the cultural and economic establishment supported this party, its rank and file consisted of ordinary people, much to the chagrin of the former.

In terms of language, following the post-World War II demise of Italian, more and more members of the elites began adopting English as their lingua franca. The arguments in favour of having Italian as Malta’s national language, which many in these groups had previously supported, conveniently evaporated (with some exceptions, as noted above) so that English could become the new mark of class distinction.

The use of English by numerous representatives of the elites was now meant to exemplify refinement, graciousness and cosmopolitanism, in contrast to the perceived insularity, coarseness and vulgarity of those who spoke Maltese. Correspondingly, ‘upstarts’s’ failure to speak English properly was (and still is) frequently considered by the top echelons of society as a mark of lower social background.

The use of English by numerous representatives of the elites was now meant to exemplify refinement, graciousness and cosmopolitanism, in contrast to the perceived insularity, coarseness and vulgarity of those who spoke Maltese.

The rest tended to use Maltese for everyday purposes, and consequently labelled the preference for the English language as an indicator of posturing and ungrounded pretense. Generally, these tended to simply resent posh groups, rather than transforming this dislike into an awareness of how cultural and linguistic hierarchies deepened social exclusion and justified mistreatment of those branded as culturally inferior.

So the chasm in the linguistic power-game now had English on the one hand associated with various elites, and on the other, Maltese affiliated with lower middle and working classes. Of course, such a sweeping picture does not do justice to the nuances: There were haute bourgeois who cherished Maltese and indeed fostered this language. This fondness however, was rarely tied to progressive political initiatives.

Maltese language was perceived by many as a mark of authenticity, identity and unpretentiousness. To some, speaking Maltese became a quintessential indicator of ‘Malteseness’. Unlike lone local figures such as Manwel Dimech and thinkers like Paolo Freire, folkloristic enthusiasts of the Maltese language nevertheless did not seem to question language politics within the neo-colonial framework.

Instead of becoming a political tool for emancipatory purposes, advocating for Maltese from an identity perspective only reinforced a conservative understanding of Maltese identity as uniform and unchanging. (Once again I am generalizing. Apologies to those who do not fit in the description.)

Instead of becoming a political tool for emancipatory purposes, advocating for Maltese from an identity perspective only reinforced a conservative understanding of Maltese identity as uniform and unchanging.

Thus, promoting Maltese as a means of preserving ‘true’ Maltese identity did not challenge existing cultural, political and economic oppression within our society, which could have been expected in the post-independence set up. It is no accident that the chair of Maltese at the University of Malta was established by the British and assigned to Ġużè Aquilina, an intellectual who was genuinely passionate about the Maltese language but whom the British authorities also considered to be politically safe.

Today, Malta’s native tongue might be appropriated for some sinister purposes.

The ‘Foreign’ Threat?

Malta’s location along one of the main immigration roots from Africa to Europe and, especially, the economic boom of the past few years have led to an increase in the number of foreign-born individuals residing in the islands.

This economic boom has resulted in such phenomena as a growing demand for workers (unemployment is negligent, but wages in most sectors are lower than the EU average) and a spiraling increase in the cost of property and rent. This state of affairs benefitted the moneyed circles, both Maltese and foreign, as well as those who—mainly due to socially inspired policies of a few decades ago—could afford their own house, and who now can add to this an apartment or two, earning an extra few hundred euros a month from rent.

The locals from a disadvantaged background, on the other hand, have generally had to foot the bill. Their wages remain poor, meaning that they have to work more than they used to in the past. Their lifestyle is deteriorating. Neither is buying property any longer within the means of many citizens. The working and living conditions of most foreign employees in the construction and catering sectors, are, given their precarious legal status and other factors, even worse. Thus, both groups are the biggest losers in this economic ‘success story’.

Logically, the two groups should join forces. Yet, they are anything but in the process of doing so. And the reasons are numerous.

One is the shortsightedness of institutions which cater for both groups; be these trade unions or NGOs whose objective is to support refugees and migrants. They tend to cater only for what they consider to be their constituency, without building bridges with other groups who, too, are on the losing end of the economic game. Groups and individuals on the Right, on the other hand, seem to succeed in convincing disadvantaged Maltese persons that ‘foreigners’ are the cause of their ills.

NGOs tend to cater only for what they consider to be their constituency, without building bridges with other groups who, too, are on the losing end of the economic game.

The ‘foreigners’ scapegoated by the Right, however, are neither the ones flocking to Malta in order to avoid higher taxes elsewhere nor the lavishly paid individuals working for offshore and gambling companies—and who have indeed contributed to the upsurge of prices in the rental market—but the overexploited individuals generally hailing from Africa, the Arab world and increasingly Eastern Europe and the Indian subcontinent. Obviously, such a division within the working class advances the interests of the fat cats who are making a killing.

In light of these developments, the language question seems also to be taking a new turn.

While a number of immigrants have managed to learn the rudiments of Maltese and are comfortable interacting in this language, others communicate with peers from other countries in English, even if it may not be their native tongue. Again, the extreme Right seems to be quick to react to this situation, and not unsurprisingly, their arguments work against the interest of the working class—local or foreign born.

According to some individuals, one area where immigrants are ‘taking over’ is language: the inability of a number of them to speak Maltese is regarded as a failure to ‘integrate’ and a threat to an essential feature of ‘Maltese identity’. Calls are being made to stop using English to ‘accommodate them’; forgetting that this language has been constitutionally recognized by Maltese representatives as an official language alongside with Maltese. The argument seems to boil down to ‘either learn Maltese or leave’.

The Language of Emancipation

What can everyone militating for progressive politics in Malta learn from the past linguistic tussles? How can we support the use of the Maltese language while not letting it become a tool of xenophobia and racial exclusion? Here are a few suggestions to consider:

- Ensure that the local working class is not mystified by this new turn in the language issue. There is nothing intrinsically ‘anti-Maltese’ in English per se. We should point out that the dichotomy between the two languages is relatively recent and was created by people who were generally opposed to working class advancement. The elite would probably have no qualms about adopting pristine Maltese as a mark of distinction if it were to serve their segregationist purposes in the future, just as their forefathers had dumped Italian without batting an eyelid when it became convenient.

![]()

- Promote bilingualism in spaces where local and foreign-born individuals meet, so that persons fluent in either or both languages feel included and are encouraged to participate. Once again, there is no natural antagonism between the two languages. Promoting one to the exclusion of the other helps cementing an artificial chasm where there ought to be none.

![]()

- Promote and support the learning of colloquial Maltese amongst those foreign workers who could benefit from it on various counts, including promoting political consciousness, solidarity, bonds and militancy. Nothing helps breaking barriers more than foreign born workers integrating into spheres where local workers hang out. The successful integration story of Karim Adams in Ħaż-Żebbuġ is a telling example.

Leave a Reply