We have collected a few stories and perspectives which contemplate on how national identity is constructed and what effect it has on our lives.

by the IotL Magazine

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat is Maltese identity? Is it a unique characteristic shared by all Maltese-born persons? Is ‘Maltese-ness’ defined by religion, symbols, language or, perhaps, a surname? Could it be that ‘Maltese identity’ is far more complex than a set of fixed habits? Finally, how do newcomers see Maltese identity and how do they relate to it?

Exploration of what lies beyond the question of national identity has always been one of the keenest interests of this publication. We have collected a few stories and perspectives which contemplate on how national identity is constructed and what effect it has on our lives.

![]()

1. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Symbols?

‘The Not-So-Maltese Cross‘ by Michael Grech

Today, the eight-pointed ‘Maltese’ cross is broadly recognised as ‘brand Malta’. It is everywhere: from tourist booklets, to the crib on Triton Square and to the Malta Blockchain Summit. However, the cross of the Order of St John was not embraced by the Maltese during the Hospitallers’ rule.

So how did the emblem of debauched foreign aristocracy become the ultimate symbol of Maltese identity? In his essay ‘The Not-So-Maltese Cross‘, Michael Grech argues that the Maltese Cross became a means to emphasize, exaggerate and at times invent Malta’s historic ties to Europe. In other words, the Cross reimagined Maltese identity as European and served to distance the country from its Semitic heritage. Read more here.

![]()

2. Is Maltese Identity Defined by a Place of Birth?

‘How Growing Up in Malta and England Changed My Understanding of Identity‘ by David Edward Zammit

As a five-year-old, I was transplanted for a year or so from the village of Paola, where my parents had started to raise me up as an ordinary Maltese speaking toddler, to Oxford in the UK. There I attended Wolvercote primary school while dad worked on his PhD and mum worked as a pharmacist’s assistant.

In 1975 and 1976, we lived in a culturally diverse block of apartments, called Summertown House, on Banbury road; sharing the block with other student families from a range of national backgrounds. Irish, Japanese, Israeli, Swedish and Indian children stand out in my recollection of the common playground. Although this was a relatively short period, it was a personal watershed; mainly because my experiences forced me to switch from being a Maltese to an English speaker and to develop an interest in reading. Both characteristics have stayed with me until the present.

Upon returning to Malta after a year in Oxford as a five-year-old, I had to face the challenges of integration all over again.

Upon returning to Malta after a year in Oxford as a five-year-old, I had to face the challenges of integration all over again; made worse by the fact that I had completely forgotten Maltese and my parents were living in Sliema. This seemed to be a world away from my memories of Paola and Malta’s “Deep South.”

These experiences have made it difficult for me to commit to a single homogenous identity and have also given me a strong sensitivity to the way in which individual identity is constructed by the gaze of the other.

Read more here.

![]()

3. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Religion?

‘But, Where Are You Really From?’ Reflections of a Maltese Muslim on Belonging and Identity by Ibtisam Sadegh

‘I am Maltese,’ I assert to those who cynically question or glare the instant I pronounce my Arabic name or refuse to drink an alcoholic beverage. ‘But, my father is Libyan and my mother is Maltese,’ I add, when the sceptical or the curious refuse my answers, take guesses at my roots or demand further clarification. The response to this reply could range from polite silence and acceptance, to the friendly ‘I have a Libyan/Muslim friend,’ or the most certainly absurd, ‘I can see it in your eyes!’

I grew up seeing my migrant father being bluntly discriminated against, treated as if he were an outsider and a parasite siphoning on Maltese society and this despite his having lived here for over three decades, his fluency in the Maltese language (although with an obvious Arabic accent), Maltese citizenship, wife and kids.

I thus learned from a young age the necessity to continuously navigate my Muslim background, maneuver my identity and emphasize my Maltese-ness.

I thus learned from a young age the necessity to continuously navigate my Muslim background, maneuver my identity and emphasize my Maltese-ness. Such daily strategies include me explaining the meaning behind my given name; at times even de-Arabizing it by abbreviating it to ‘Ibti’ or writing inquiring emails in formal Maltese—all in attempt to be recognized and treated as equally Maltese.

Read more here.

![]()

4. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Surnames?

‘Go Back to Your … Gozo?‘ by Raisa Galea

To some people, my surname seemed more important than the causes I wrote about.

When after my wedding I was able to choose whether to adopt my husband’s family name, the decision came quickly.

If my foreign surname fed into prejudice—if it truly was an obstacle to sound debates—then a Maltese surname was an opportunity to support just causes without prompting unnecessary animosity. The experiment was a success.

If Raisa Tarasova (a Russian) was told to return home whenever she protested an ODZ development, the very same arguments stirred engagement when they came from Raisa Galea (an ordinary Maltese). The contrast in feedback was so stark, it called for an investigation of its own. I decided to find out whether this was a common experience that other foreign residents encountered after having adopted their Maltese spouse’s surname. The findings were even more insightful than I expected.

While foreigners who take on their Maltese spouses’ family names gain an advantage, Maltese adopting foreign surnames are subsequently alienated from public debates.

While foreigners who take on their Maltese spouses’ family names gain an advantage, Maltese adopting foreign surnames are subsequently alienated from public debates.

Read more here.

![]()

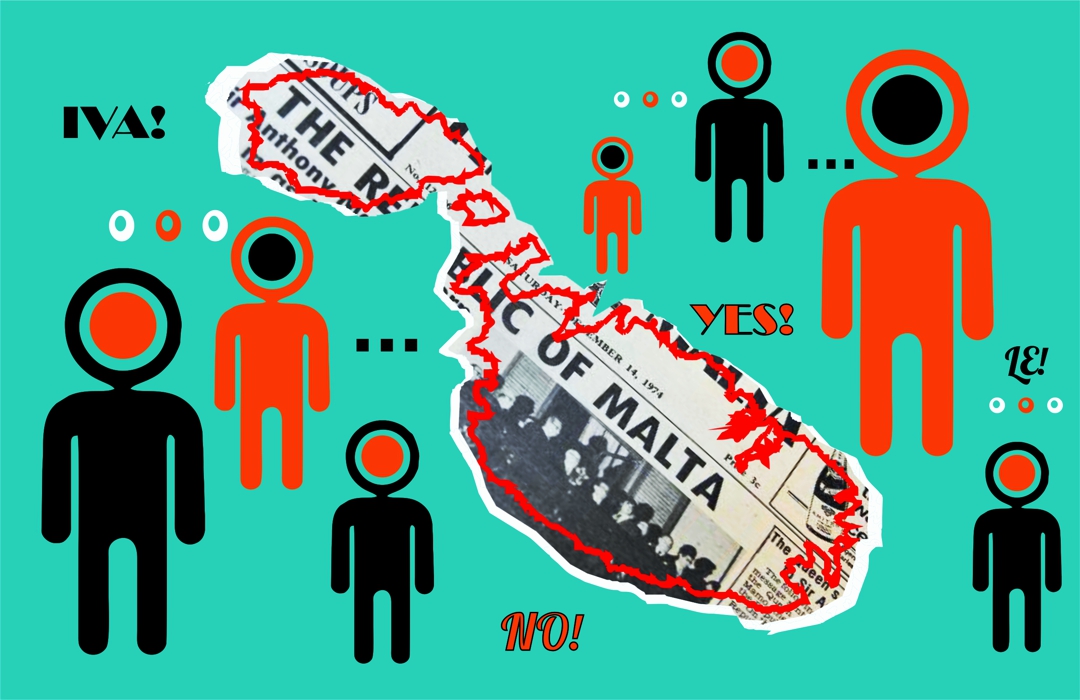

5. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Language?

‘Malta’s Language Puzzle: Malti vs English‘ by Michael Grech

Malta’s language question has been a subject of an ongoing debate for over a century. Today, our native tongue might be appropriated for some sinister purposes.

According to some individuals, one area where immigrants are ‘taking over’ is language: the inability of a number of them to speak Maltese is regarded as a failure to ‘integrate’ and a threat to an essential feature of ‘Maltese identity’. Calls are being made to stop using English to ‘accommodate them’; forgetting that this language has been constitutionally recognized by Maltese representatives as an official language alongside with Maltese. The argument seems to boil down to ‘either learn Maltese or leave’.

How can we support the use of the Maltese language while not letting it become a tool of xenophobia and racial exclusion? Promote bilingualism!

There is nothing intrinsically ‘anti-Maltese’ in English per se. We should point out that the dichotomy between the two languages is relatively recent and was created by people who were generally opposed to working class advancement. The elite would probably have no qualms about adopting pristine Maltese as a mark of distinction if it were to serve their segregationist purposes in the future, just as their forefathers had dumped Italian without batting an eyelid when it became convenient.

Read more here.

![]()

6. Is it Possible to be a Non-Maltese and a Local at Once?

‘How I Have Become a Local in Malta: On Local Foreigners and Foreign Locals‘ by Raisa Galea

After many years in Malta, separating my own experiences from those of the locals feels uncomfortable because I have become a local myself.

To integrate was to recognise the diversity and the complexity of Maltese society. I could no longer utter a phrase like “all Maltese are rude” or “all Maltese are racists” because I knew it was not the case. Maltese are different—a platitude from Captain Obvious which was not at all obvious a few years ago. I thought I could define fairly well what a ‘lack of integration’ means: inability to recognize diversity of a host society.

It is the relationships with the locals—Maltese and non-Maltese, uncaring and sensitive—that make me part of Malta’s social fabric.

It is the relationships with the locals—Maltese and non-Maltese, uncaring and sensitive—that make me part of Malta’s social fabric. I admire Malta of green fields and colourful balconies as much as I am repelled by the ever-expanding construction sites and the corporate developments. I sympathise with the Maltese who struggle to afford their rent and barely make their ends meet (just as do my relatives back in Russia) as profoundly as I decry the market-worshiping developers and tax-dogging companies.

Read more here. You can learn more about the author’s experiences of integration from this episode of Good Faith Podcast with Christian Peregin.

Leave a Reply