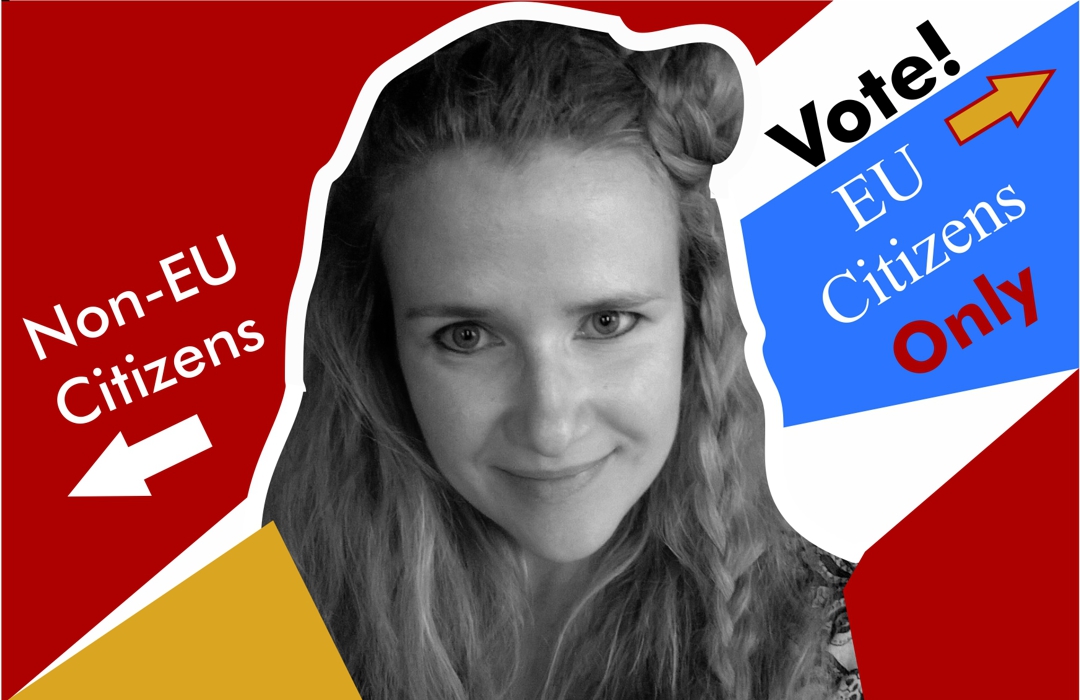

Despite having spent a decade in Malta, I still am a guest here—a non-EU resident who cannot afford to purchase Maltese citizenship. I cannot vote either in local council or European Parliament elections. Simply put, I am unrepresented.

by Raisa Galea

Image by the author

[dropcap]N[/dropcap]othing reminds me of my inferior status in Malta more than a pre-electoral delirium. This is the time when I feel voiceless, powerless and unrepresented. Not having full political rights means being excluded in a fundamental way. Moreover, in a country where a vote is the priciest currency and a voucher of power, not having it is akin to non-existence.

I have spent a decade in Malta—that is, a third of my life. I’ve seen it change, and the experiences of these years have shaped my understanding of the world. With no exaggeration, I feel more at home here than in my place of birth; I’ve got accustomed—even comfortable—with living in this perpetually erupting volcano. And if speaking the language is the ultimate proof of ‘integration’, I tick that box, too. I can support a conversation in Maltese and, to my detriment, understand it well enough to follow Maltese politicians without subtitles.

Yet, despite all of the above, I still am a guest here—a non-EU resident who cannot afford to purchase Maltese citizenship. The proposal to increase women’s representation in parliament by introducing gender quotas has been received with both fanfare and criticism, but none of it applies to persons like myself. I am a woman, albeit one with a wrong kind of passport—hence I cannot vote either in local council or European Parliament elections. Simply put, I am unrepresented.

I am a woman, albeit one with a wrong kind of passport—hence I cannot vote either in local council or European Parliament elections. Simply put, I am unrepresented.

Although gender quotas were advertised as a radically progressive move, they do not address the fundamental lack of representation. It must be said that neither are all men living in Malta represented in parliament. African and other non-EU male workers are men, yet their wrong kind of nationality—and ‘wrong’ skin colour—isolate them as social outcasts whose voices remain ignored.

Maltese voters are well aware of their vote’s power—they wave it in the face of prospective candidates, seeking ways to trade it for tangible advancements like favours, contracts or permits. Personally, I do not strive for this kind of opportunity. All I want is to have a say on the present and the future of the country that I regard as home, but which nevertheless does not fully reciprocate.

Malta is the one of the most bureaucratic and rigid states when it comes to granting citizenship by naturalisation. Newcomers are encouraged to ‘integrate’ and to blend in, but at the same time are instructed to stay away from active participation. Their needs are dismissed; their discontent and civic enthusiasm can be easily brushed off with the painfully familiar go-back-to-your-country.

Newcomers are instructed to ‘integrate’ and to blend in, but stay away from active participation.

How can foreign residents become an integral part of the country if they have no voice and cannot express their civic concerns? If integration means to perform according to local customs—and given the prominent role of voting in the lives of locals—anyone who has spent more than five years here must be granted an opportunity to fully integrate—by voting.

![]()

Giving non-EU residents a right to vote could have a major revitalising effect on Maltese politics.

Extending the right to vote in national and local council elections could cause a significant blow to clientelism. Since non-Maltese residents move to Malta alone or together with a small number of family members, they do not belong to extensive family networks which form the foundation of the clientelist structure. And this is why they are more likely to vote for policies and principles rather than immediate personal favours.

Speaking of political representation, I would have been marginalised even if I were a citizen with a right to participate in elections, since the type of democratic socialism that I stand for is completely unrepresented on the Maltese political landscape.

Considering that a large number of non-EU residents are paid minimum wage and thus not prospering, their inclusion into the electorate could finally revive the real Left-of-center politics. The needs and demands of this—least affluent—section of the population would have to be addressed by the political parties, which in turn would benefit the interests of lower class Maltese people, making them a force to be reckoned with.

Extending the right to vote in national and local council elections could cause a significant blow to clientelism.

Finally, even the incumbent political party has something to gain from giving non-EU nationals a right to vote. Although the Labour Party currently enjoys majority support, this may not last for long if Malta is hit by an economic crisis. The experience of the Democratic Party in the US shows that new voters tend to support the party that granted them the voting right, which means more votes in times when they are needed.

In their majority, debates on integration revolve around cultural aspects, but in the spirit of democracy, the most important facet of integration is being part of a political community.

For as long as substantial sections of the population are excluded from political representation and participation—be it in Malta or any other EU country—democracy will remain incomplete and vulnerable. Unrepresented and dismissed, guest residents will always be a mere tool in times of economic growth and convenient scapegoats in darker times.

Leave a Reply