By responding with art, beauty and civic concern to the chaotic and hostile environment of one of Malta’s most urbanised towns, Nimxu Mixja achieved the impossible. Even if for a brief moment, it reclaimed space from car dominance for pedestrians.

by Raisa Galea

Picture by Elisa von Brockdorff

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]y journey to the exhibition Nimxu Mixja—which was on display at the Mill, Birkirkara, until June 14—began with a walk. I walked along Birkirkara bypass, and instead of following the familiar route, decided to take a different turn. This improvisation led me to a part of Birkirkara I had never previously visited: I strolled past a baroque palazzo, an elegant chapel and a row of stunning townhouses before realising that I was lost.

After 20 more minutes of walking on narrow, often obstructed pavements, and twice being almost hit by a car, I finally found my way to the Mill. Getting lost and arriving on foot, however, was the best possible introduction to the exhibition, whose curators Kristina Borg and Raffaella Zammit are both aficionadas of walking.

As Kristina and Raffaella guide me through the exhibition, a photograph immediately captures my attention: a caterpillar of school students wearing bright-yellow safety vests walking on the pavement. Pictures of children usually elicit tender melodramatic emotions, but this one stirred a bolder feeling: it occurred to me that, although peaceful, a group of children walking on narrow pavements in a chaotic urban area of Birkirkara was similar to Gilets Jaunes rioters in Paris. In a car-dependent society such as contemporary Malta, a simple act of walking can appear as radical as a riot.

On second thoughts, there is more in common between Nimxu Mixja (a serene artistic project) and Gilets Jaunes (a raging riot) than a safety jacket: they both strive to reclaim civilians’ right to mobility. The Yellow Vests insurrection began as a protest of ordinary French people against the fuel tax which threatened to undermine their mobility. In France, the yellow vest was a symbol of disenfranchised residents of suburbs and rural areas who had to commute to cities on a daily basis for work and whose livelihood depended on the use of private vehicles. Nimxu Mixja participants, on the other hand, quietly reinstated pedestrians in a space suffocated by cars.

Walking as Artistic Exploration of Urban Space

Inspired by a spontaneous comment on social media back in 2017, Nimxu Mixja evolved into an elaborate artistic exploration of space for pupils of Birkirkara Primary School.

The project consisted of five sessions, performed separately for each of the four classes involved. The preparatory sessions focused on introducing the parents and the children to the concept of the project. The pupils’ initiation to Nimxu Mixja began with mapping their experiences of Birkirkara: they identified familiar places, nature, water and sites they considered as heritage.

Prior to the start of the project, walking did not occupy a prominent role in the children’s lives; they associated it mainly with a fitness routine and transportation, but did not deem it a pleasant activity in its own right. This perception of walking gradually changed over the course of Nimxu Mixja.

The children associated walking mainly with a fitness routine and transportation, but did not deem it a pleasant activity in its own right.

The curators designed five routes around Birkirkara to be explored over the six months of the project’s duration: four student walks, each lasting approximately an hour, and the final community walk that brought the students, parents and local community together. Keeping in line with the artistic dimension of the project, participants were encouraged to reimagine Birkirkara through the use of different senses such as sight, hearing and smell. Each walk also had a specific theme.

The first walk titled “Letting Go” took the children on an exploratory journey to places they had never visited or been completely unaware of. The variety of Nimxu Mixja’s positive outcomes absolved the many logistical challenges the organisers had to face. Seeking to expose the children to as many experiences and types of spaces as possible, the curators realised that there weren’t any accessible green public areas in Birkirkara, which is why the pupils were taken to St Aloysius’ orchard—a private garden belonging to the order of the Jesuits.

Curiously, bureaucracy made invisible boundaries between towns frustratingly tangible: Kristina and Raffaella could not obtain a permission for an excursion to a nearby public garden—whose guardian, too, seemed to be out of reach—that is formally assigned to Balzan, but can also be accessed from the Birkirkara side.

The two other places the pupils visited during the first walk were a scrap yard—an abandoned space hidden away from sight—and the Mill. Despite its location in close proximity to one of the busiest roads, not many participants were aware of the art, culture and crafts centre which was to host the project exhibition.

Themed “Lines and Shapes”, the second walk focused on various lines, shapes and patterns found in the newer and older parts of Birkirkara. During the third walk, the young pedestrians were taken on a tour through two distinct areas of the town and were asked to take note of their observations. They also walked along the valley watercourse that has been completely channelised.

The fourth walk (“Places and Our Community”) introduced the students to the place names and local history: they visited the old railway station, learnt about its history and walked along the former train track. This session brought the topics of history and mobility together: the children got to know about a different means of transport that existed in Malta in the past, but is currently unavailable.

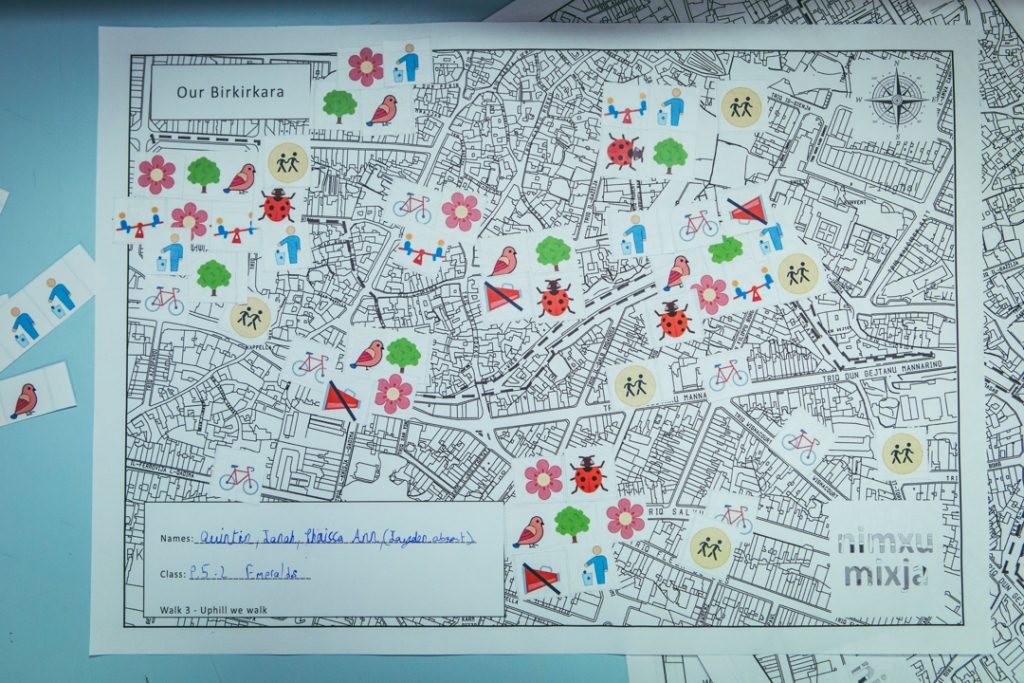

During hands-on sessions, children reflected on the streetscape they observed during the previous day, each time expressing their thoughts in a different medium: the first walk transformed into poems in Maltese and English; the second—into improvised maps of the stroll’s route, which captured the young pedestrians’ sense of direction. The third post-walk session was an envisioning exercise for the children to imagine their Birkirkara, while the fourth and final session reflected on all the previous ones and developed into artworks expressing calls for improvement of the town.

The project ended with a bold exclamation mark: on Sunday June 2, 2019, the final community walk reclaimed one of Malta’s busiest transportation arteries from cars.

The project ended with a bold exclamation mark: on Sunday June 2, 2019, the final community walk reclaimed one of Malta’s busiest transportation arteries from cars. Kristina and Raffaella earnestly recall the genuine excitement of the strollers on that day: a few hundred people—adults and minors—arrived at the Mill on foot and bikes; accompanied by a few dogs and a pony, they marched in one colourful procession right in the middle of the busy Naxxar Road, which was closed to cars for the occasion.

The Many Portraits of Birkirkara by Young Pedestrians

Although walking on narrow, frequently obstructed pavements of an urbanised, noisy area may not seem an inspiring experience at first glance, Nimxu Mixija did splendid work on translating the children’s impressions into striking artworks. Not only do statements appear more powerful when expressed in poetry and graphics, they also inject beauty and thought into the otherwise plain discomforting urban architectonics.

With the assistance of renowned poet Miriam Calleja, every smell, every tactile and visual experience of the first walk was captured in poetry, written in either Maltese or English. Students pointed at and lamented noise, garbage bags and dog feces as most common features of the town’s pavements. They also struggled to spot nature. Bizarrely, as the children themselves put it, grass on roundabouts was their only experience of nature.

The second walk engaged the junior pedestrians’ sense of shapes, lines and direction. After having walked for an hour through the narrow lanes of Birkirkara’s historic core and the gridded modern districts, the pupils were asked to draw the route from memory; the memorised routes were then superimposed with the actual one. The session demonstrated the excellent orientation skills the majority of children possessed—skills they practically never have a chance of practicing since they are driven around most of the time.

Using the cameras in their school tablets, the pupils photographed the artifacts they encountered along the way—carved iron features of townhouses, railings and other decorative architectural features that caught their eye.

The slogan messages prepared during the fourth, conclusive post-walk session addressed their perceptions and concerns related to Birkirkara, and then were utilised as hand-held signs during the final community walk.

A sign stating “replace noise with flowers” immediately draws my attention. One may not think of delicate physical objects as a possible replacement for jarring sound waves, but this is where the artistic dimension of the project and youthful wit shine through. Despite its apparent naive cuteness, this piece of carton echoes the legendary “be realistic, demand the impossible” or, of course, “beneath the pavement, the beach” slogans of the May 1968 riots in Paris.

The outcomes of Nimxu Mixja offer plenty of food for thought. Prior to the thematic walks experience, nothing had challenged the students from growing up into another generation of car users. Since children are taken to school by car or school bus, they practically never experience their home town outside of a vehicle; areas that are only a few blocks away thus remain uncharted territory.

A society in which the simple act of walking feels as radical as an insurrection and where roundabouts are the only spots of nature ought to question its ways and means. Locked in airtight shells of schools, private houses and cars, deprived from any contact with the outside, the future generation of Maltese citizens are simply unaware of the loss of public, open, green spaces and heritage. Children or adults, how can we notice the disappearance of something we have never experienced in the first place?

Indeed, by responding with art, beauty and civic concern to the chaotic and hostile environment of one of Malta’s most urbanised towns, Nimxu Mixja achieved the impossible. Even if for a brief moment, it reclaimed space from car dominance for pedestrians. It introduced the town to its inhabitants. Most importantly, however, it carved an avenue for junior pedestrians’ civic expression which we all should pay attention to: let us, too, support the realistic demand to replace noise with flowers, as impossible as it may seem.

Nimxu Mixja was supported by Arts Council Malta’s Kreattiv fund. For more information and updates, follow the project’s Facebook page.

Leave a Reply