Good bye, Paul. You remain in the thoughts, memories and deeds of all of those whom you challenged and inspired.

[…] And death shall have no dominion.

No more may gulls cry at their ears

Or waves break loud on the seashores;

Where blew a flower may a flower no more

Lift its head to the blows of the rain;

Though they be mad and dead as nails,

Heads of the characters hammer through daisies;

Break in the sun till the sun breaks down,

And death shall have no dominion.

Dylan Thomas

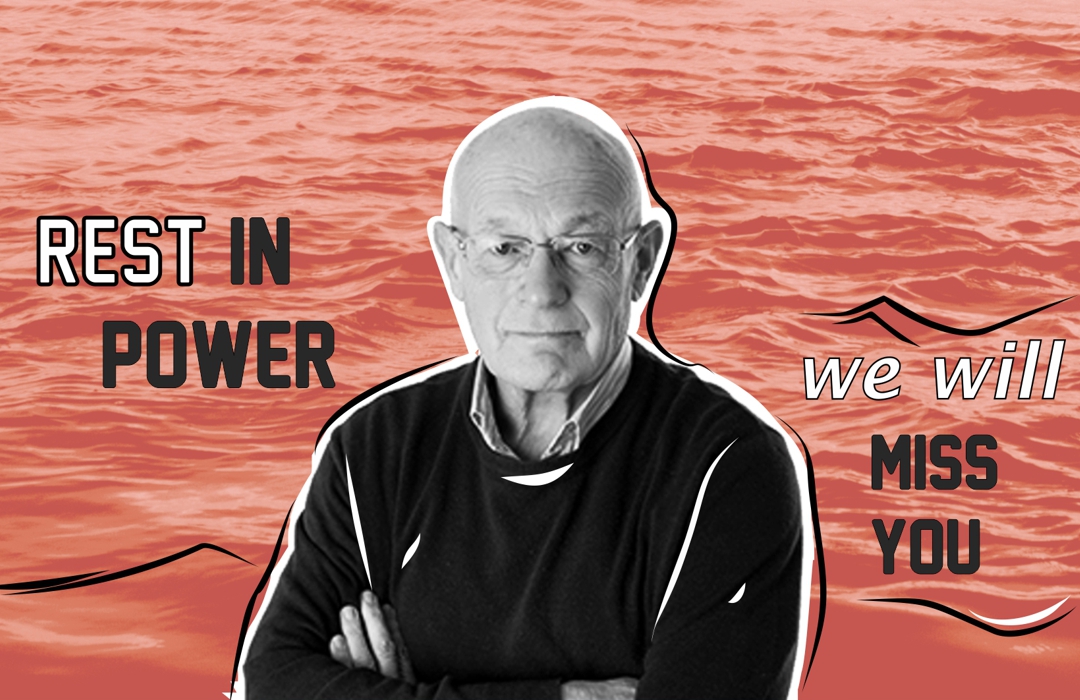

[dropcap]P[/dropcap]aul Clough left this wretched world—the world he was so engaged with and fascinated by—on Thursday, 25th July 2019. His departure left everyone who knew him with a sense of immense, irreplaceable loss; many of us feel shaken, desolate and orphaned.

The last time Paul and I communicated was only a day before his sudden passing. The editorial team of this magazine believed the project was incomplete without his contribution and, despite the many items on his agenda, he kindly agreed to write an article “on capitalism and the environment in Malta—mainly theoretical, unfortunately—but quite short”. He mentioned he would be unable to send it before September and I deployed all my rhetorical stubbornness to convince him to write it sooner—for the sake of injecting incisive arguments into the stagnant public debate on the matter.

The editorial team of the IotL Magazine was anticipating Paul’s contribution with thorough enthusiasm. Never could we imagine that his name would feature in this project for the first time posthumously! In the last email I received from him on July 24, 2019 at 12:05, he wrote “I can tell you that Isles of the Left is now being mentioned by many people. You are a fixture of the Left in Malta! […] So well done and good luck!!”

We believe it is our duty to pay Paul Clough a tribute as complex, honest and multi-faceted as the person he was, although no tribute can ever do justice to his true dimension. We are mourning the death of a friend, daring non-dogmatic thinker and inspiring engaged intellectual whose influence on the local and international thought was profound. Good bye, Paul. You remain in the thoughts, memories and deeds of all of those whom you challenged and inspired.

Raisa Galea,

the founder of the Isles of the Left Magazine

Paul Clough: Isles of the Left’s Guardian Angel

An appreciation by former colleagues and students

![]()

Rachael M Scicluna,

a former student, friend and colleague

Housing & Social Planning Consultant, Parl. Sec for Social Accommodation, Malta

Words cannot even come close to expressing who Paul was, and what he meant to me personally. He was a complex character with so many facets—a bit like a diamond. His energy and light reflected and refracted, with deep seated intellect and wisdom. He weighed words with sensitivity and caution. His reflections were never superficial but always intellectually and spiritually reflexive. I can still picture him as I write this—head bent slightly down, with eyes tightly closed and a hand over his forehead. He would then take a deep breath, nod with affirmation and a new world would be presented to you in response to a simple question. He was a genius.

His teachings in class were inspirational and contagious. Paul always taught us theory from practice. He challenged us through his own academic challenges. I believe the classroom was his therapeutic space to make sense of his own theoretical dilemmas. He showed us pictures from his long-term fieldwork with the Hausa in Nigeria.

Besides being a distinguished scholar and an outstanding anthropologist who always bridged practice and academia, he always had social justice at the core of whatever he did.

Paul asked us to be inquisitive, to question the status quo and to look closely at the mundane. He would show us pictures from his fieldwork over and again and ask us to describe what we could see. In that way, he taught us about: ‘difference’; about humanity; temporality; and the fluidity of social, economic and political relations. His own torments with disciplinary and methodological boundaries were insightful and real—for example, his switch from a sociologist to an anthropologist was not superficial but it emerged from ‘being-there-in-the-field’. It was then that he realised that positivism, it’s often calculative stance and the rational ‘hypothesis’ of supply and demand in relation to agricultural produce did not fit at all in a polygynous society and the Hausa economic framework.

Instead, Paul explained that mode of production was weaved into the polygynous kinship, gender and religious system. He called this, polygynous capitalism—an alternative form of capitalism which was less mechanistic and was somehow dependant on the domestic sphere and domestic relations of power such as marriage and divorce, children played a key role in its economic success and the reproduction of domestic and social relations too. That was a technical lesson which I took with me. Later on as a doctoral student doing fieldwork in the metropolis of London I found extremely helpful.

Besides being a distinguished scholar and an outstanding anthropologist who always bridged practice and academia, he always had social justice at the core of whatever he did.

During my university days (2005-2008), our year revamped the Anthropology Society with Paul’s insistence and enthusiasm. We were so inspired by his teachings that we actually ventured in exploring classic anthropological theories in action. How? We ventured out in the world and attended local events. We took the opportunity to dress up in order to study carnivalesque rituals and the theories of communitas (see image below).

We were encouraged to integrate with migrants. How? Paul facilitated meetings with West African migrants as he collaborated with them during his fieldwork in Malta. We organised one of the most successful public ethnic meals on campus. That day over 200 people attended. The ethnic meal was accompanied by West African dancing and music. Here are some nostalgic pictures from the night.

At the end, and to our surprise, Paul addressed the crowd in Hausa language which was followed by a roar of applause and clapping. That night was electric. That day many understood the concept of the ‘other’ through the exchange of food. That’s how we understood the power of food as ritual. This type of teaching is so powerful because its intensity becomes embedded in your body (embedded is one of Paul’s favourite words). Paul taught us how to look at the world through the periphery.

Last year, a group of us (some anthropologists) organised another ethnic meal in Marsa—we called it Breakfast on a Bridge, but the concept stayed the same as that of the Ethnic Meal back in 2006. We invited Paul and he attended with his beloved dog Spark. I am so glad that he did as that Sunday morning I told him, ‘Thank you Paul for your teachings. This is your legacy.’ As per his usual, he nodded and smiled.

He was also a mentor as I am sure he was to many others. He especially comforted me when I had to traverse to new unknown terrains in my career. As a Housing Consultant for the government, I invited Paul to act as our expert when the Research and Policy Team worked on the White Paper on the private rented sector. He played a pivotal role through his astute advice as he told us, ‘Without a good labour force this reform cannot happen.’ That’s the Marxist in him. But he also consoled us by stating that any small step towards the ‘management of the rented sector’ would be a great and bold step forward. He reminded us that Malta, like other southern Mediterranean societies, is a culture of concealment. I can still hear his words echo in my ears, ‘Go for a light touch form of management’. His support and courage helped me do my part with faith and without fear.

In his last correspondence as he invited me to deliver a paper at the next WIPSS seminar, ironically, I said that I am ‘drowning’ in work and that I had booked a holiday in Sicily. He got back and his email dated 19th July said: ‘I think I must follow your idea and get away NOW for a long weekend. I am tired out and need to pick up speed!!’

He surely left a legacy which will live on in all of us who were honoured by his greatness and genius.

I will miss you!

Love,

Rachael

![]()

David Edward Zammit,

Head of Department of Civil Law, University of Malta

On my fiftieth birthday I received the news of the sudden and unexpected passing away of a dear mentor, friend and colleague: Prof. Paul Clough. Paul grew older as I want to do: with undiminished zest for new adventures, friendships and conversations. He eagerly entered into new constellations of relationships without abandoning old ones and always found time for quiet reflection in which he could re-create his self.

These last few months were a period of particularly intense reflection for him; in which he was moving towards a more spiritually detached but intellectually engaged contemplation of the issues he wrestled with as an anthropologist: how do moral choices structure temporality, while being themselves temporally configured?

He passed away while engaged in one of his favourite activities: swimming in Saint Paul’s Bay. I know from recent conversations I had with him that these last few months were a period of particularly intense reflection for him; in which he was moving towards a more spiritually detached but intellectually engaged contemplation of the issues he wrestled with as an anthropologist: how do moral choices structure temporality, while being themselves temporally configured, how to understand the particular shape that modernity takes in various societies (especially Malta and Nigeria), is it possible to move beyond mechanistic models that emphasise accumulation and rational action while building upon the key insights of Marx and Weber?

Ultimately I am sure that Paul’s eager and relentless search for an answer to these fundamental questions, his engaging teaching style (to which he gave his all), the energy with which he adopted and pursued new theoretical insights from a vast and eclectic range of anthropological sources, the many students he mentored, will outlive him and his quest will be carried on by and through all those people whom he inspired and conversed with. We all miss him terribly. Goodbye Paul!

![]()

Mark Anthony Falzon,

Head of Department of Sociology, University of Malta

I first met Paul in 1994. He was a part-time tutor in anthropology, which at the time was run by Paul Sant Cassia. I think Paul Clough and Sybil O’Reilly Mizzi (another fondly-remembered academic and friend) became full-timers in 1995, and I was their first and only Honours student. I got to know Paul better when he became my dissertation supervisor. I would spend several hours at a time at his flat in St Paul’s. He would smoke, suck on his trademark mints, and talk: about Oxford, his hero and mentor Polly Hill, Uncle Marx, his parents, Nigeria, his dog (Tramp, if I remember well), and his plans for anthropology at University. It was anything but vacant chatter.

Paul’s knowledge, and his generosity with it, were remarkable. He would urge me to be empirical, and to steer clear of the intellectual culs-de-sac that threatened to reduce anthropology to impressionistic wordplay. Paul was rigorous and expected his students to reciprocate. I once told him I had been to Liz Groves’s bookshop and bought a stack of titles. His reply was that he didn’t believe books had a hau (‘spirit’, rudely translated). It was his polite way of telling me that buying books was not enough, and that it helped to also read them. That year or so was a time of intense learning for me—there simply was no other way with Paul. It helped that he didn’t have a bad bone in his body. Paul was one of the most honest, generous, and affable people I have ever known. I’ve a lump in my throat as I write this, because you couldn’t but love the man.

He would urge me to be empirical, and to steer clear of the intellectual culs-de-sac that threatened to reduce anthropology to impressionistic wordplay. Paul was rigorous and expected his students to reciprocate.

I was lucky enough to find another Paul figure in Cambridge. James Laidlaw, now the William Wyse Professor of Anthropology, turned out to have all the wisdom you might expect of an Oxbridge don, but none of hauteur. Which is not to say Paul was replaced. We corresponded very regularly, and we would always meet up for a drink whenever I was in Malta. As chance would have it, I ended up in another department when I came back, and we didn’t get to work as closely together as we might have. Still, his sound advice and friendship were always there when I needed them. I can only hope he thought the same.

The one thing that everyone will say about him is that he was loyal to the University and tremendously giving with his students and colleagues. All of it is very true indeed. I last saw Paul a couple of weeks ago over lunch. We talked about his students, his plans for the research seminars, and his sabbatical. I urged him to set aside some time for himself, and to make sure he didn’t miss his daily appointment with the sea in St Paul’s Bay.

![]()

Judith Melita Okely,

Affiliate, School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography, Oxford University, UK

Like so many others, I am still in shock to learn of Paul Clough’s sudden death. I first met this future friend in the late 1990s when I returned to Malta, my birth place and contributed to a conference on persons of the Mediterranean. I had indeed been born in Malta, the daughter of two Brits at the height of the WWII bombing. I was baptised at the Anglican Cathedral in a superb christening robe embroidered by Maltese nuns. I was forcibly evacuated to Egypt then South Africa, aged about 14 months, with my mother. My second name Melita was in honour of the island. Paul, being a fellow anthropologist who had also studied at Oxford, made contact and provided up to date contexts.

He subsequently invited me to give lectures in his department. I also witnessed his lectures, seminars and discussions with his students. He displayed exceptional commitment. I could see the results when meeting, lecturing and marking the students’ essays and exams. Never casual towards his teaching, Paul’s courses and background reading were inspiring, often at the expense of his own writing and continuing research. His drafts for journals had to be ever perfect. Indeed his PhD submission took years longer than usual, just as with his eventual monograph based on decades of intensive and highly original research in Nigeria: Morality and Economic Growth in Rural West Africa: Indigenous Accumulation in Hausaland (2014).

Through the years, we met at conferences throughout Europe and the USA.

Paul’s innate commitment to ethical conduct sometimes made him more vulnerable to others’ contrary schemes and perspectives.

Always he had fulsome updated insights. Here was a trusted friend. We could confide in and seek advice from each other. Inevitably, I interviewed him as a key anthropologist for my fieldwork methods book Anthropological Practice (2012). The selected extracts are proof of his innovative and imaginative approaches: always ready to change and adapt to the unexpected among the Nigerian Hausa peoples he would live with, learn from, and analyse.

There is a superb example where he responded to one person’s request that he measure their land acreage. Although distracting and time consuming, he agreed. Soon a neighbour observing this, presumed he, as white stranger, was doing it for his own benefit and shouted disapprovingly at him. Paul exploded with vigorous Hausa swear words. He was doing this inconvenient distraction out of generosity, benefitting nothing. Confronted by this melodramatic reaction, the accusers expressed amazed admiration for this white man’s uncontrolled emotion. Suddenly he was perceived as human like them. This marked a new stage of his acceptance blossoming into friendship.

Paul’s innate commitment to ethical conduct sometimes made him more vulnerable to others’ contrary schemes and perspectives. He was endlessly bemused by my ethnographic anecdotes and first hand experiences of corruption and sexism in UK academia. Any imagined utopias elsewhere disappeared. Through the years, he consolidated a total commitment to his current position and elaborated teaching. This included a superb encouragement of student contact with refugees in local centres.

He identified the inmates’ different cultural origins and encouraged cross-cultural exchanges through music making, relevant festivals and meal making. Students were meeting face to face the ‘others’ once limited to the printed word. Paul responded creatively to the challenge of strengthening and editing the Journal of Mediterranean Studies. He encouraged me to contribute an article ‘Hybridity, Birthplace and Naming’. Again, I witnessed first hand his supportive enthusiasm and attention to detail.

Malta, the place his Anglo-American parents had chosen for settled retirement, offered ever unanticipated openings. The visits back to his parents and siblings, when he was Oxford postgraduate, or doing fieldwork in Nigeria, eventually brought alternative local university links. He familiarised himself with the islands’ geographical, historical and architectural magic. Thanks to his knowledge and guidance, I was shown the full range of globally celebrated or hidden places in Malta, Gozo and surroundings: the locality which, through decades, became Paul Clough’s home.

![]()

Symphony No. 5 by Gustav Mahler. It is playing for you, Paul.

![]()

Jean-Paul Baldacchino,

Head of Department of Anthropological Sciences and Director of Mediterranean Institute

Paul Clough, Professor in Anthropology at the University of Malta has died at the age of 70. He was a pioneer in the development of anthropology at the University of Malta. Completing his PhD at Oxford he joined the University of Malta in 1993 and headed the Department of Anthropology for thirteen years.

He was an active member of the University community and was the general editor of the Journal of Mediterranean Studies for more than a decade (1999-2013). He was a committed unionist and has served on the executive council of the University of Malta Academic Staff Association since its foundation in the 1990s. A long standing fellow of the European Association of Social Anthropologists (EASA), Paul was a regular contributor to International Conferences and has published on a range of topics.

Paul was a leading scholar in the field of African studies with an intimate knowledge of West Africa. His book Morality and Economic Growth in Rural West Africa was published by Berghahn Books and has been hailed as ‘the new gold standard of anthropological field research on African economies’. Since 2005 Paul started conducting research among West African irregular immigrants in Malta. He was deeply interested in the interface between morality and economy. Paul was a true scholar and an assiduous field researcher with a passion for ethnography. His fastidiousness in research and writing was only matched by his commitment to his informants.

A political economist, a Marxist and a deep Catholic Paul was a passionate lecturer and an unwavering humanitarian with extensive roots in the community.

A political economist, a Marxist and a deep Catholic Paul was a passionate lecturer and an unwavering humanitarian with extensive roots in the community. He has supervised numerous students and helped countless others in their research and has mentored a generation of anthropologists. He will be mourned by his sisters and nephews, his colleagues at the University and many students who owe Paul an irredeemable debt of intellectual gratitude.

To those of us who had the pleasure of having gotten to know Paul over the years he will always be remembered for his warmth, good humor, generosity of spirit, his insight and most of all his humility. Paul’s passing has struck a blow to the heart of Maltese Anthropology and academia, the echo of which will resound for many years to come.

![]()

Jana Tsoneva,

a former student

Death is a strange dialectic of absence and presence. As soon as I learned of Paul’s untimely departure, a dizzying barrage of memories of my time in Malta overwhelmed my mind. They pivoted on Paul: my favorite professor at the University.

Paul taught us with passion, rigor and with his inimitable sense of humor. He managed to put in simple terms, but without simplifying, complex theories and texts and make them interesting for us, a bunch of clueless BA undergraduate students. If anyone who has ever tried to keep people in their early 20s concentrated on Weber for more than 20 seconds, knows what I am talking about!

He managed to put in simple terms, but without simplifying, complex theories and texts and make them interesting for us, a bunch of clueless BA undergraduate students.

He was the kindest and most patient instructor but even he lost patience with us on a rare occasion. Once the entire class showed up without having read the text for the session and he did not hide his disappointment. We loved him to bits, though. Paul did not teach us only the classics but made sure we were up to date with the latest developments in the discipline, the novelties being delivered by their very originators.

To this end, Paul ensured regular visits by foreign anthropologists, exposing us to world-class scholars first-hand, while placing firmly the department on the map of anthropology globally. The department focused his tireless efforts and it did pay off: Paul’s network of colleagues span across Anglo-American anthropology and we were lucky to have rubbed off it and met scholars who left indelible marks on our minds and thinking. These extraordinary sessions with visiting professors always culminated with long dinners, lots of wine and good conversations.

I absolutely loved our departmental outings. In no small part due to them we turned from a randomly gathered cohort into friends. And Paul was the engine of the unstoppable crazy machine that churned curiosity, love for anthropology and for the people, amazing conversations over wine, challenging intellectual tasks, parties and laughter, making my University years the unforgettable and beautiful experience that helped me find my place in life.

Thank you for everything, Paul. I will never forget you! <3

![]()

Michael Deguara,

Visiting lecturer, Department of Anthropological Sciences, University of Malta

When I handed in the first draft of my undergraduate dissertation, I was very concerned about framing my observations within solidly established theoretical frameworks. I thought I had done a fairly good job, but after getting feedback from Paul Clough, then my tutor, I scrapped the whole thing and rewrote it. I don’t remember all the details of the feedback that Paul gave me that day, but one piece of advice stands out in my memory, given in his inimitable style: “Fuck the theories—I want to hear the stories.”

This is not to say that Paul wasn’t heavily interested in theory himself. Indeed, theory was very much one of his primary concerns, particularly the theory of morality. Rather, what he was driving me towards was a realisation that the importance of theory in anthropology is primarily that it helps us critically understand the human experience, which needs to take pride of place. This sensitivity to the complexity of people’s experiences, accounts and worldviews is especially important when working with people who are marginalised or oppressed, such as the homeless men I was doing research with in those days, and the migrants with whom Paul had been working closely for over a decade. In both situations, incidentally, Paul’s long-time friend Terry Gosden, who sadly passed away last year, was an important connection.

Paul’s work, in this case, brought a particular individual to life—making migration not simply an abstract, bureaucratic principle, but a relatable lived experience.

Enthusiasm and storytelling were among Paul’s innate gifts, and a significant part of what made him such an inspiration to many. In social gatherings and personal conversations, he often had us short of breath with laughter, regaling us with hilarious but thought-provoking anecdotes. In the lecture halls, he introduced students to a critique of the received wisdom of neoclassical economics: courtesy of Marcel Mauss on the gift economy, Marshall Sahlins on hunter-gatherers as the original affluent society, and his own work with the Hausa-speaking people of Nigeria which looked at the way in which the acquisition of capital was subordinate to local concerns related to marriage and the building of networks.

His dedication to social equality also showed clearly in his work with migrants in Malta. In particular, his heartfelt but accurate and insightful descriptions of the plight of migrants in Malta proved to be a breath of fresh air in a social climate often characterised by fear, mistrust and even hatred. One paper, to my best knowledge sadly unpublished, made use of biography as a way of making migrant experiences concrete and palpable. Paul’s work, in this case, brought a particular individual to life—making migration not simply an abstract, bureaucratic principle, but a relatable lived experience.

As groundbreaking as Paul’s anthropological work was, his greatest impact may yet have been the care he gave to his students and colleagues—not only as regards academic work but also in terms of personal and intellectual development and social engagement. This impact will live far beyond Paul’s untimely passing, through the many people whose lives he has touched, and who now owe it to his memory to leave the world at least a slightly fairer, more egalitarian place.

![]()

Rachael Radmilli,

a friend and colleague

Assistant Lecturer at the Faculty of Economics, Management & Accountancy, University of Malta

Last June, Paul and I participated in a panel (at the MARE conference) that Tom Selwyn organized in Amsterdam in memory of Jeremy Boissevain. We both gave a paper on our latest research. While listening to his presentation I sent this message to Vicky Sultana: “I forget sometimes what a brilliant mind Paul has. He gave a wonderful paper.” To which she replied, “He is a brilliant mind. I miss him in many ways…”

He didn’t use any fancy powerpoint presentations, just his hand written scribblings in blue ballpoint on his large notebooks. There was no need for embellishment. There was that something about the way he articulated his thoughts and argument, weaving Jeremy into the story. Linking up to Jeremy’s theoretical contributions and his own empirical findings while working with the migrants in Malta who he truly loved. Nigeria was his field. Working on the Muslim Hausa communities there, and now following up so many African stories of the migrants, Muslim or not, Nigerian or not, on their complicated routes over the sea.

The same sea that took his life! The same sea where his own journey came to an end.

His memory though will live on. The stories have been pouring in from the acquired ‘family’ who know him well—the many colleagues who considered him a true friend, brother, mentor and ally. Not only because of his academic strength, but also because of his good heart and the total support that he offered to so many. Erdinç Cakmak placed a wonderful comment on a post I put up on Facebook announcing Paul’s untimely demise. And this comment reflects the true ‘Paul effect’—he was an honest person—very much a case of no frills. So people could see right through him. Erdinç said: “RIP Paul.. So sad news.. It has been just a month when we talked over new projects.. You were such an energized active person thinking of how to increase the quality of life in your community.”

Working on the Muslim Hausa communities there, and now following up so many African stories of the migrants, Muslim or not, Nigerian or not, on their complicated routes over the sea. The same sea that took his life! The same sea where his own journey came to an end.

He was indeed always ready to help. Such an understated person. And not ready to die as Tom Selwyn said, correctly. He had so many ideas for projects, books, articles, and travels that still needed to come to life.

He also loved anthropology deeply. Alex Strating, my tutor based in Amsterdam, told me about another younger colleague who only met Paul once at an EASA conference in Vienna several years ago. Now that news is spreading through the international academic community he sent Alex a message remembering this one common encounter. They had drunk quite a few beers. And this colleague commented that while most dedicated anthropologists would switch to mundane topics of conversation after a couple of beers, Paul would still talk anthropology: even after the tenth beer! Although Paul had a sociology formation, anthropology was right at the centre of his existence.

Paul will forever be remembered as a warrior, a wonderful thinker, a sensitive and ever so gentle soul. And a person who had a humble sense of adventure. We spoke about holidays in Italy, and in our last phone call on Wednesday he said that maybe he should return to this country that took him back to his youth. We spoke about Puglia which linked him up to the works of other students of his, like Michael Deguara. He promised to call Michael to get a few tips as he liked the idea of visiting a strange place that was relatively undiscovered by the tourism hordes.

The next day, though, he died in the sea that connects us.

On our last morning in Amsterdam when the conference ended, I took him to ‘De Papegaai’, a hidden Catholic church on Kalverstraat which I believe impressed him. One side of him that I wasn’t aware of was that he was a practising Catholic. He lit a few candles and sat in a pew for a few quiet moments. Who knows what his thoughts, at that point, were? And then we went for a wonderful Dutch ice-cream (the legit kind). And there too although constantly searching for the authentic, a childlike joy came out when he ordered the largest option available and giggled while he dug into it. Mmmm he said, this is like a second breakfast. Yum! There was always something new to discover about Paul, although I had first met him in October of 1994 as a first year anthropology student.

In life, there were two things that bothered him: the fear of depending on others in his old age, and retiring from University life which was his world. Perhaps, the Universe knows what she is doing after all, as she dealt him one big blow that sealed his fate. He passed away quickly once the academic year had closed, barely six weeks before going into semi retirement while his mental facilities were intact and while he still enjoyed a fully independent life. A rich one at that. This may be a small consolation for all those he left behind. No ordinary death, but perhaps a perfect one to suit his perfectionist nature.

We will miss him. A man we all loved and admired. May he finally be resting in the peace he always sought. A stark reminder of our own mortality.

My most sincere condolences to his family.

With love and gratitude,

Rachel

![]()

Jon P. Mitchell,

A friend and colleague

University of Sussex, UK

I first met Paul during my first and longest spell of fieldwork in Malta, from 1992-1994. He, like me, had begun teaching on the newly-established Anthropology programme at Malta University, under the leadership of Paul Sant Cassia. Paul Clough was then finishing off his Doctoral thesis, and beginning the process of transforming himself from a rural Sociologist/Political Economist into an Anthropologist. The motivation? His recognition that economic relations are also always moral relations, and that economic actors might accumulate not in straightforwardly economic ways, but also in ways informed by culture.

Paul was fascinated by the ways in which Anthropology could nuance (Marxist) political economy, and present empirical ethnographic evidence that could turn received economic wisdoms on their head. In 2002, we collaborated on the edited volume Powers of Good and Evil, in which we explored precisely this intersection between economic process and culturally-informed moralities. His monograph, Morality and Economic Growth in West Africa was not only a triumph of empirical social science, but also presented a new theory of the morality of economic accumulation in rural life.

Paul was fascinated by the ways in which Anthropology could nuance (Marxist) political economy, and present empirical ethnographic evidence that could turn received economic wisdoms on their head.

Paul was always on the look out for new ideas—new ways he could think through his field research—in rural Nigeria, and latterly among West African migrants in Malta. A chance conversation would lead to him frantically scrawling titles and authors—and what a scrawl he had!—in one of his many pocket notebooks. Next time you met him, or read one of his drafts, the suggestions had been fully filleted and either thrown back at you or carefully incorporated into his interpretive schema.

What always struck me the most about Paul, though, was his ability to engage with, support, and get the most out of others. As a teacher to the many students who passed through his classes, he was personally engaged and encouraging. As a friend and colleague he was generous beyond bounds; and he remembered details. When we got together in Malta we would talk the usual gossip, but also talk Anthropology, and on countless occasions he would bring up details of previous conversations—which had faded in my mind from the mists of time and the odd drink—to point out that I’d changed my position on certain key issues. I, of course, had no idea. He was right.

It is this attention to the personal opinions and ideas of others; this careful recollection and studious observation of growth and change in others; this generosity of mind and spirit; that I shall miss in Paul. His life touched the lives of so many others. It is so sad that he will not be able to touch the lives of more.

![]()

[…] And death shall have no dominion.

Under the windings of the sea

They lying long shall not die windily

Dylan Thomas

Elise Billiard,

Anthropologist, visiting lecturer at the Department of Sociology at the University of Malta

Paul Clough was a renaissance intellectual in the sense of a renaissance man, capable of provoking an intense discussion about almost any subject and with anyone willing to delve into the complexities of social life. To me, his life exemplified what anthropology could be: open to the world, fiercely engaged but rigorous and, ultimately, truly inspirational.

He was genuinely open to perspectives that would challenge his ideas, a position that is sadly not so common in academia, and which is exemplified in particular by his confrontation of his Marxist upbringing to the Hausa realities he encountered in Nigeria, or his desire to take a biographical turn in his recent fieldwork with Africans living in Malta which took him far from his original university background in economic sociology .

The only thing I could never come to terms with him was his dislike for Pierre Bourdieu’s theories. I guess he was too much of a free spirit to abide to what he probably saw as social identity determinism. But all friends have disagreements, they made for good discussions. And although I met him first as a French doctorate student coming from a different academic background, he did not hesitate to invite me to give what were my first lectures. In the years that followed, we shared a common desire to create public encounters to engage with a wide audience.

Although he died in total anonymity, his body taken by the waves that took so many other beautiful souls, yet his legacy is impressive. A legacy that cannot be accounted by auditing, likes or book sales.

His constant enthusiasm for debate made him a great speaker and experienced chairperson in public discussions. After having listened carefully to other speakers he would always come up with a surprising and insightful remark that would open the debate on new horizons. Once, after a dance performance of Jelili Atiku at Castille square, he explained to an audience accustomed to contemporary art issues, the immense creativity of Yoruba cosmology around the ambiguities of gender.

The previous year he had surprised the panel of academics and an audience of Paceville residents by taking on the courageous role of the defensor of Paceville nights as the much needed pocket of licentious behaviors in Malta.

Our last exchange, only a few days before his departure, focused on the postface he was writing for a book on Paceville’s recent urban plans. At the end of his email, with his typical mischievous tone, he proudly declared that he had stayed until 3am in Paceville a few nights before, and he liked very much my suggestion that we could fairly justify his late encounters with the fact that he was in effect doing research fieldwork for our book. That was Paul. Rigorous in his reflexion, but happily free and humble with people around him.

I cannot help to think that his departure encapsulated his life. Although he died in total anonymity, his body taken by the waves that took so many other beautiful souls, yet his legacy is impressive. A legacy that cannot be accounted by auditing, likes or book sales. A legacy that is much more than this. Paul is still with us because he inspired a great variety of the women and men that are today working hard for a better society.

![]()

Victoria Sultana,

a friend, mentor and colleague

Visiting Lecturer at the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Malta

Professor Paul Clough came into my life in 2002 and he remained a very prominent actor in it until his death. He was a dear friend, a mentor and a person who I looked forward to spending time with whenever our busy schedules permitted it. We supported each other through rough times and we celebrated the good times together across the years.

I simply cannot imagine life without Clough and all he brought to it—his passion for poetry, literature, classical music, theatre and his eccentricities which made him the man we all loved.

Paul was a true anthropologist. He studied life and meditated on situations methodically with an interest and a passion which was contagious. Paul built his arguments like a skilled lace maker—he was able to weave multiple threads into his writing to produce intricate and fine monographs.

I simply cannot imagine life without Clough and all he brought to it—his passion for poetry, literature, classical music, theatre and his eccentricities which made him the man we all loved. Over the years we shared many a deep conversation over a bottle or two of good red wine and during such time the beauty of his soul revealed itself—a soul which was in constant search for meaning, a soul which is now at rest.

![]()

Gavin Williams

PhD Tutor and colleague

Paul was my first doctoral student and Oxford, and still holds the record: 19 years, 1977-1996 for completing. His first two years of field work opened him to a subtle understanding of the economic ethnography of rural Hausaland with far-reaching implications for the interpretation of rural peasant societies. He acquired an appreciation of Polly Hill’s classic studies of Rural Hausa and Studies in Rural Capitalism, showing how the numbers, observation, and conversation could show how credit relations, social inequalities were capitalist, but not as Marxists thought them to be.

![]()

Requiem for My Friend by Zbigniew Preisner. It is playing for you, Paul.

Deborah Bryceson

A friend and colleague,

Professorial Research Associate, Nordic Africa Institute, University of Uppsala

I knew Paul in the early to mid-1980s when we were both DPhil students in Oxford, under the supervision of Gavin Williams. Both of us were studying peasant farming communities, Paul’s in Northern Nigeria whereas I had done my fieldwork in Tanzania. Peasant studies was a very hotly debated area of sociology. We were both members of a small group of post-graduate students who were reading hefty chunks of Marx’s Das Kapital month by month, with the aim of better understanding the capitalist world at large and indeed our fieldwork sites.

Our focus was on the nature of peasant commodification, the role of the nation state and global market in commodification processes, the evolving local divisions of labour, and class, gender and generational stratification in agrarian communities. Paul was a meticulous field researcher with an incredibly detailed household data set covering the demographic composition of the households, their land holdings, labour practices, productive output and hierarchical patterns within the household. His analytical understanding of the workings of the agrarian households he researched was formidable.

Paul was a meticulous field researcher with an incredibly detailed household data set covering the demographic composition of the households, their land holdings, labour practices, productive output and hierarchical patterns within the household.

Paul was generous in sharing his insights with the rest of us, and together we discussed the similarities and differences between agrarian patterns in different parts of Africa. His D.Phil thesis was a monumental work that came out after years of patient dissection and analysis of the data. During the last visit Paul made to Oxford some months ago, he was excited about what he had recently observed on a return visit to his original field site after over 25 years away. The generational restructuring of the households and the effect on land and labour usage was a topic that he was excited to write up. He had taken copious field notes which I hope will be preserved in some accessible place for future scholars of Nigerian rural studies.

Besides Paul’s outstanding contributions to the literature, he was known to be a highly inspiring lecturer who devoted a great deal of his time to his students. He will be sorely missed by so many people in Nigeria, Britain, Malta and beyond.

Peter Mayo,

a friend and collaborator

Professor at the Faculty of Education, University of Malta

I have known Paul for about 23 years. We collaborated closely on the Work in Progress in the Social Sciences (WIPSS) seminar series. Our joint interest in left wing social theory and Gramsci in particular brought us closer together. He would invite me to deliver a session on Gramsci to his Anthropology students and likewise to WIPSS audiences. He was intrigued by the fact that I had been taught at the University of Alberta, during my Master’s studies, by UK sociologist Derek Sayer, whose work on and around Marx he read and greatly admired; the copy of Readings from Karl Marx I lent him has remained in his possession ever since. We would discuss mutual areas of academic and political interest.

He was the first to encourage my work, and that of colleagues, in Museum Education as Cultural Politics, first urging us to present on the subject at one of the early WIPSS sessions and later to submit a piece around the area to the Journal of Mediterranean Studies (JMS). He would later invite me to join him as one of the coordinators for WIPSS. Make no mistake, Paul was the driving force behind WIPSS. He put his heart and soul into this and into running the editorial collective for JMS which would constantly feature in our conversations. I will never forget how deeply upset he was when the University turned down the chance, for which he put in a colossal effort, to have the journal produced by the distinguished publishing house Berghahn.

Paul would feel so passionately about things that he would never mince his words, as when he let the Pro-Rector and academic staff know, in no uncertain terms, of his frustration at the new levels of bureaucracy he felt were being introduced. At that meeting at University, he had the courage to blurt out his feelings, which I am sure were felt by many others, myself included, who remained silent.

Paul would feel so passionately about things that he would never mince his words, as when he let the Pro-Rector and academic staff know, in no uncertain terms, of his frustration at the new levels of bureaucracy he felt were being introduced.

Apart from being an inspiring scholar of genuinely international calibre, blessed by some wonderful students, some of whom I taught thanks to him, Paul had so much creative energy. This, I believe, was infectious—the mark of the sort of academic who can broaden frontiers for a University such as ours. I do not think he received due credit from the institution for this. He was also one of that rare breed who measured their own output according to the highest international standards. The book that emerged from his research among the Hausa in Northern Nigeria was reviewed, with acclaim, in top international journals such as Capital & Class.

He managed to attract a number of top scholars to our University through either the Fulbright or other schemes. He had a knack for choosing the right setting for some of their presentations, such as the old Presbyterian Church in Floriana for a presentation, by a top German sociologist, on Weber’s Protestant Ethic in an event meant to mark the 100 anniversary of the production of this classic or the then newly refurbished Archaeology Museum for a presentation on Museums. What was amazing was his ability to connect with any argument put forward by speakers at the WIPSS sessions, including the odd one who would be so abstract as to border on the unintelligible.

This ability to engage in dialectical exchange with different people, and on a range of topics, attested to Paul’s stature as an intellectual. And he was very much a social scientist engagé. Strongly committed to confronting social injustice, he would be present in many anti-racist and also pro-Palestinian rallies. He was one of a handful of non-African people at University who would be present for activities organised by the now defunct Society for African Studies, led by African students, in the late 1990s; I mean one of around three ‘white’ people in all. He was at the heart of many activities intended to foster inter-ethnic understanding and solidarity. His engagement with the migration issue, on the side of the oppressed and marginalised in this context, knew no bounds.

Humble, socially committed and intellectually engaging, Paul will be sorely missed. With more people like him around, the world would be in a healthier state and our University would provide a much more intellectually stimulating environment than is the case at present.

![]()

Caroline Gatt,

A former student,

Honorary Research Fellow, University of Aberdeen, UK

I first got to know Paul when I began reading anthropology in 1998. He was our lecturer and the Head of the anthropology Division, as it was then within the Mediterranean Institute. As so many others have said, his energy and passion immediately caught my attention, and kept it not only for the four years of the course but for all these years in my work in anthropology since those first days. This is not only because I have pursued anthropology as my profession, but because of the way I live and strive to develop my anthropological self was shaped by Paul’s ways of thinking, questioning and relating.

Paul did not deliver anthropology lectures as stand-alone information, but as a path to a particular type of ethical self-formation. With complete generosity, Paul offered his students a way of life, not just a career. Paul always found time to talk and guide, to give detailed feedback on essays (even if it was often illegible). He welcomed us into his home for parties and gatherings; students were, in his way of relating to us, junior colleagues whom he openly expressed a joy in spending time with. With all the different ways of relating Paul gave me, and all his students, a way of life. With all our thanks and gifts to him I don’t think I ever properly acknowledged him for this until now, when I realise I can no longer phone and tell him.

He loved life and pleasure and health. He introduced me to the rich world of Queer Theory and what diversity had to offer to social justice.

While it is true, as many have said, that his approach to anthropology was deeply concerned with social justice, he was also constantly questioning. He never assumed what justice meant, or where the social could be located. Paul introduced the other-than-human and ecology into our undergraduate courses long before many other European Anthropology departments were doing so. But Paul also had the spirit of coyote, a trickster, able to work with different powerful persons and entities while keeping his indomitable independence of thought.

He loved life and pleasure and health. He introduced me to the rich world of Queer Theory and what diversity had to offer to social justice. A social justice that seems on the one hand to be reaching places we barely hoped for in the 90s, but on the other hand to have regressed in shocking ways. We are facing times when the sort of academic, and person, Paul was (engaged, committed, critical, creative, passionate, hopeful, light hearted and deeply serious, a terrific gossip, a fiercely loyal friend), is how we all need to be. I hope we find the courage to step up, to openly question and take a leaf from Paul’s book.

![]()

Brian Campbell,

a former student

Lecturer, University of Plymouth, UK

I first met Paul in his office in the summer of 2005. I was to start my Bachelor of Arts course that September, and I was on the look-out for a relatively un-intrusive “minor” subject that would not get in the way of my main interest in Geography. I had never heard of anthropology before, and I left the meeting with this strange American lecturer—who told me all about what I thought was an unreasonable amount of time living with a forsaken tribe somewhere in Africa—with a sinking feeling: I wanted an easy and highly-relevant topic, and anthropology seemed to be neither. But time was running out, and I signed up anyway.

Two months later, I applied to make Anthropology my “major” subject. Thirteen years down the line, I am still unsure whether I would have made the switch if any other person had been teaching the subject. His two-hour seminars seemed to me more like trances than lectures. Paul expertly immersed us in cultures close and far, and then showed us how to pry them apart to reveal powerful truths about human behavior. These were truths which we could—and did—apply to the society we lived in. Only the failure of his whiteboard marker (tip mashed into a flower) or the nudge of the low-hanging TV shelf in that small seminar room of the Old Humanities Building would jolt us back to the world… and every time we felt as if a shroud had been removed from or eyes, and that the world seemed clearer now.

I guess the role Paul played in my life changed whenever I acceded to a new stage of my journey as an anthropologist. The fact that he played a decisive role in each of these stages is a direct testimony to Paul’s insight, experience, kindness, dedication and remarkable ability to understand what people need at any particular moment. Therefore, when I embarked on my PhD journey, it was Paul who urged me to go to Ceuta and explore this small enclave on the edge of the Mediterranean. The fact that I had never been, could not speak the language, and had no idea what to find was something to be embraced not rejected. We chatted throughout fieldwork, and he always urged me to go out into the streets, especially when all I wanted was to stay in my room and away from Ceuta’s deadly politics, sickening poverty, and frightening neo-fascism.

His two-hour seminars seemed to me more like trances than lectures. Paul expertly immersed us in cultures close and far, and then showed us how to pry them apart to reveal powerful truths about human behavior.

As a fresh post-doc, we discussed the next stage of my career, where to focus my energies, how to manage university politics and, most importantly, how to stay human throughout it all. As I did further field-research, he also reminded me that it was ok to change my mind about my own conclusions, as long as they are based on meticulously collected data: data he had taught me how to meticulously collect (“and stop building castles in the sky, Brian!”).

As we met in conferences and workshops, we became colleagues, and I was impressed by how frankly Paul could treat me as an equal and, with time, as a friend. I enjoyed our long chats about our new theoretical ideas. And when I was doing my (nowadays practically obligatory and thankless) phases of zero-hour lecturing, it was Paul who reminded me of the importance, value, and joy of teaching … regardless of what institutionalized channels of promotion said.

Perhaps it is because I will be soon once again stepping into a full-time position that I remember him, first and foremost, as the most inspiring of teachers. His ability to make us fall in love with the discipline of anthropological thinking, to make us hungry to learn more, to turn our cohort of students into one of the most vibrant societies on campus, was utterly unique. His ability to nudge you towards the next stage of intellectual difficulty at exactly the right time was unparalleled, and again shows his utter attention to every single one of his students.

As I prepare my courses—incidentally, the same courses he taught to the same number of students—it is his model that I try to imitate. Our last lengthy exchange, which happened but two weeks ago, was an exciting reminiscence of those golden undergraduate days, which I can but hope to give to the students I will encounter. It wouldn’t just make me a good teacher, it would be my way to keeping Paul forever with us.

Thank you, Paul. I hope there will be poetry (and Fado) where you are.

![]()

“It’s life that matters, nothing but life—the process of discovering, the everlasting and perpetual process, not the discovery itself, at all.”

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Idiot

![]()

Marguerite Pace Bonello,

Anthropologist

“I am a giant. Stand up on my shoulders, tell me what you see”. The refrain from Giant (Calvin Harris and Rag’n’Bone man) could well have been written with Paul Clough in mind.

Paul was indeed a giant in many ways. Physically he was above average, intellectually he reached great heights and his generosity of spirit was immense. He always encouraged his students to stand upon his shoulders and share their thoughts and ideas. The exchange was never symmetrical but students did not feel patronized.

The practicalities of life seemed to interfere with his intellectual pursuits so he ignored them until they became crises. Emotionally, he also had his demons and struggled to vanquish them.

The ‘giant’ was only human and he had his idiosyncrasies and his faults—some endearing and exasperating. The practicalities of life seemed to interfere with his intellectual pursuits so he ignored them until they became crises. Emotionally, he also had his demons and struggled to vanquish them.

However none of his troubles affected his dedication to anthropological research and teaching. There are not enough words to express the gratitude of his students.

![]()

Alex Dimitrovski,

a former student

The very first time I walked into Paul Clough’s classroom, I was merely intrigued by a subject I knew very little about: anthropology. Within a month, I had no doubt that I wanted to be an anthropologist.

It is hardly a rare thing for an academic to be passionate about their subject, but Paul had that exceptional ability to transmit to those around him that same passion and dedication with which he approached his chosen discipline. Paul didn’t just talk about the Hausa, the Nuer or the Trobrianders’ culture—he would venture there during a lecture, and he’d take us with him to learn about kinship, exchange or social structure and forget everything we thought we knew about ourselves and the world.

But if Paul ever taught us what, or how to think, it was incidental. What he did teach us, or at least never tired of trying to, was to love Thinking, and like the philosophers of old, to live a life of rigorous thought and reflection.

But if Paul ever taught us what, or how to think, it was incidental. What he did teach us, or at least never tired of trying to, was to love Thinking, and like the philosophers of old, to live a life of rigorous thought and reflection. More than a mentor, he was a friend to everyone who cared enough to be close to him. He was my friend. There is far too much that I owe to his support and encouragement to speak of here. He will be greatly missed and never forgotten. Farewell, Paul.

![]()

Jeannine Vassallo,

a former student

Prof. Clough taught us how to think logically, to write clearly, to look deeper, to question incessantly and to keep learning. These were gifts, which Prof. Clough shared with us through his bespoke style and teaching methods. I apply these skills every day, in the course of furthering my studies, at my workplace and in daily life. They have enabled the acquisition of further knowledge and the development of new abilities; facilitated relationships and experiences; stimulated reflection, which has encouraged me to improve myself as an individual and the systems within which I function. For these, I am truly indebted and forever grateful to Prof. Clough.

![]()

The violin concertos are playing for you, Paul.

![]()

David Napier,

Professor of Medical Anthropology, Department of Anthropology at the London’s Global University, UK

To speak with Paul Clough on any serious subject was to know that you were in the presence of a singular mind. To speak with him on the same subject over an extended period was to know that his mind was great, even if his self-criticism at times prevented him from publishing, and from promoting his own career as a corollary enterprise. His ethnography on West African trade, for example, is considered transitional to anyone who knows the subject: carefully developed from decades of cumulative thinking.

In truth, however, his carefulness as a thinker was not specific to any one subject. It emerged across his life as a deep part of his personality. What Paul did as an anthropologist, he did well, and also tried doing well in his own life—waiting years, even decades, before publishing ideas that could have been less elegantly made public (and to his professional benefit) much earlier. In other words, his life also unfolded at its own independent pace.

Though, by example, our time as students at Oxford overlapped by more than a year (we were both finishing up in the late 1970s and early 1980s), I did not know him or the depth of his thinking when we were students. Indeed, we were both immersed at the time in our own work. It was not until decades later, when we shared the supervision of a then-student named Victoria Sultana, that our professional interests merged in the form of an abiding friendship, involving any two of the three, and often all three of us together.

Long nights of conversation at Vicky’s home in Mellieħa sealed those friendships—almost always nourished by her excellent food. In vino veritas: the enjoyment was contagious. As our friendship expanded, so did our company—including my wife, Anna; my late mother, Pauline; Vicky’s extended family and friends; and even our family dog, Wagner (when Paul returned our Malta visits). For Paul was always ecumenical in his relationships, and dogs were our match—often equal or better than humans in sensing hypocrisy.

What Paul did as an anthropologist, he did well, and also tried doing well in his own life—waiting years, even decades, before publishing ideas that could have been less elegantly made public (and to his professional benefit) much earlier.

However, that ecumenical spirit emerged for Paul most overtly in his writing. Unsurprisingly for an introvert who specialized in extroverted thinking, Paul became a regular contributor to our European Forum on Culture, Rights, and Health (a meeting that an ad hoc group of us organizes in Ascona, Switzerland, as time and funding allow). Because of the growing African diaspora, Malta’s central role in migration debates, and his own sensitivity for the common weal while sometimes living on its edges, Paul became deeply interested in social perceptions of outsiders and in our everyday fears of the foreign. More recently, he talked openly about the impact of migrants on his personal life, contributing insightfully to Migration, Reconciliation, and Human Wellbeing—a forthcoming volume that will, alas, only go to press later this year.

Now, I know that many present at Paul’s funeral will have more personal stories to tell about him. So mine is actually professional; for Paul’s extraordinary insightfulness became real to me when he noticed patterns in my work that I had not seen during the many years in which I studied medical science, and immunology in particular. In a 2016 group discussion in Cultural Anthropology, for instance, Paul wrote on the moral economy of self and other, presenting ideas that stood out alongside views of some of the best-known names in our discipline and that exemplified Paul’s high-order innovativeness.

It’s a remarkably thoughtful piece of writing. While most of our group focused on parallels between clinical ideas about disease and personal concepts of self and other, Paul explained in an entirely new (and I must say prophetic) way how xenophobic notions of infection and pollution also fuel a sharp rise in reactionary thinking, and in political narcissism especially. In fact, though such ideas seemed unusual only a few years ago, today they are openly accepted as obvious.

This lag in our social response is important: Paul helped pave that road, even if we now find it difficult to acknowledge the personal isolation and hard thought required by him to be well ahead of the rest in predicting the future. This he did with no small success on so many nights alone in his Saint Paul’s Bay study—alongside his dogs, Floppy, and, more recently, Sparky, and, of course, on the many days he swam alone.

In truth, my sadness at his unexpected death is really quite selfish—realizing now that I cannot benefit from the mutuality I had come to depend on as part of our friendship. My farewell, then, is not only to a dear friend and colleague, but also to that part of my own growth I had hoped to explore and share with him. Indeed, his presence in my life—eclectic, considered, and above all kind—will now only be acknowledged when I look to him for the sharpness of his insights, only to find them not before me in conversation. This being inevitable, I can only hope they will continue to be heard from somewhere over my shoulder.

Leave a Reply