“National Anthem”, a solo exhibition by Kevin Mallan is a verdict, a protest song and, in the artist’s own words, “an outcry for this island and what the order of the day has become to signify”.

by Raisa Galea

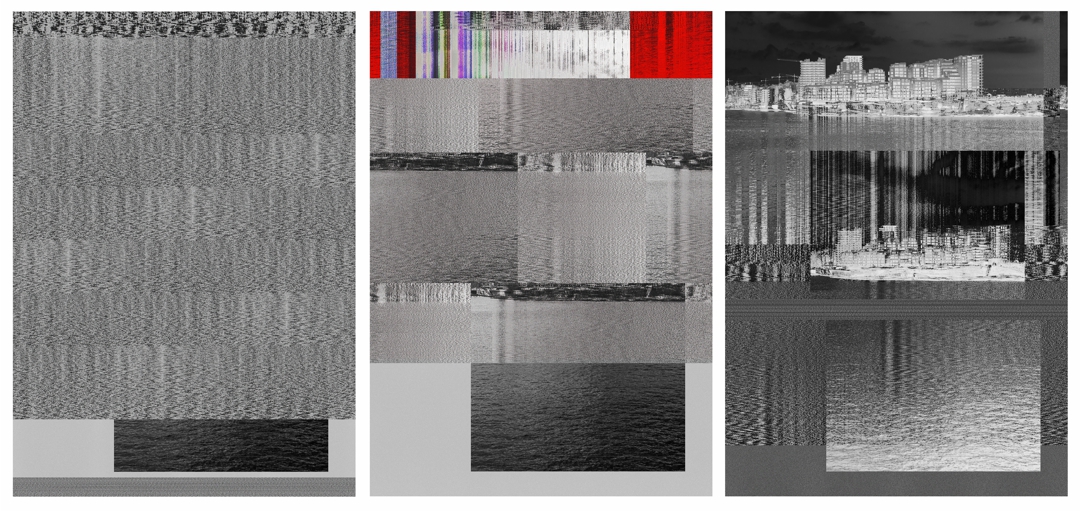

Image: ‘National Anthem’ by Kevin Mallan (detail, colorised).

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne of the most fascinating qualities of art is its openness to the world: anything, even the most trivial, most innocuous or the most atrocious events can inspire it. Art is a prism which absorbs the surrounding beauty, banality and abomination and reflects it in a structured and aesthetically meaningful way. It molds the chaos of our anxiety-struck existence into beauty.

In terms of its capacity to inspire art, Malta’s developers’ lobby deserves an award no less than Xirka Ġieħ ir-Repubblika—for the past few years, it has been the number one catalyst of creativity in the country. This statement could come across as bitter sarcasm, but it is so only partially: as our urban and natural environment is rapidly changing beyond recognition, Maltese artists are responding to the profit-driven chaos with striking projects. “In Between Obliterations” by Maxine Attard, “Ħaġraisland” by Isaac Azzopardi, “The Cement Truck Procession” by Margerita Pulè are but a few of the many artistic responses to the grim realities of an island-wide construction site.

“National Anthem”, a solo exhibition by Kevin Mallan in collaboration with Friends of the Earth Malta, which was on display from 26 July to 3 August at Julian Manduca Green Resource Centre in Floriana, is a verdict, a protest song and, in the artist’s own words, “an outcry for this island and what the order of the day has become to signify”. As was the case with Mallan’s previous project “Landings”, the works are conducted as part of his Master of Arts Photography studies at Falmouth University.

On the one hand, the works reflect on the driving forces behind Malta’s ecological disfigurement in a dispassionate, almost clinical way, akin to a medical practitioner examining a critically ill patient. On the other hand, they expose the islands’ beauty, lost and remaining. The works are executed in the palette of Malta’s national flag: white, red and shades of grey, with snippets of gold, blue and—the most mistreated of all colours—green.

One of the installations features fifteen pieces of paper, neatly framing a Maltese passport, placed on a golden background right in the center of the work. This could be an improvised altarpiece representing the supreme religion of our age—the cult of the free market, which regards everyone as simultaneously consumers and products, irrespective of their religious orientation. Here, a Maltese passport is the ultimate symbol of faith—a crucifix of sorts—and a variant of Medieval indulgence: it is a passport to paradise on Earth, an absolution from the purgatory of border control and restricted freedom of movement, available for purchase at the relatively modest price of 650,000 Euro.

To the left of the passport, there are prints of areas defaced by development—Pembroke and Marsascala—sacrificial lambs of the God of economic growth. To the right—collages of city- and landscapes undergoing development. The top and bottom rows of the installation are idiosyncratic ‘psalms’ that pass a verdict on our dismal state of affairs: “You are the citizens of commercial production and false desires,” reads one. “Public means for private gains”, echoes another.

Here, a Maltese passport is the ultimate symbol of faith—a crucifix of sorts—and a variant of Medieval indulgence: it is a passport to paradise on Earth, an absolution from the purgatory of border control and restricted freedom of movement, available for purchase at the relatively modest price of 650,000 Euro.

Besides an altarpiece of neoliberalism, the installation could be interpreted as a notice board announcing recent economic developments and advertising the country’s assets for sale. A passport, a shoreline, a valley—all commodities waiting their turn to be converted into profitable assets.

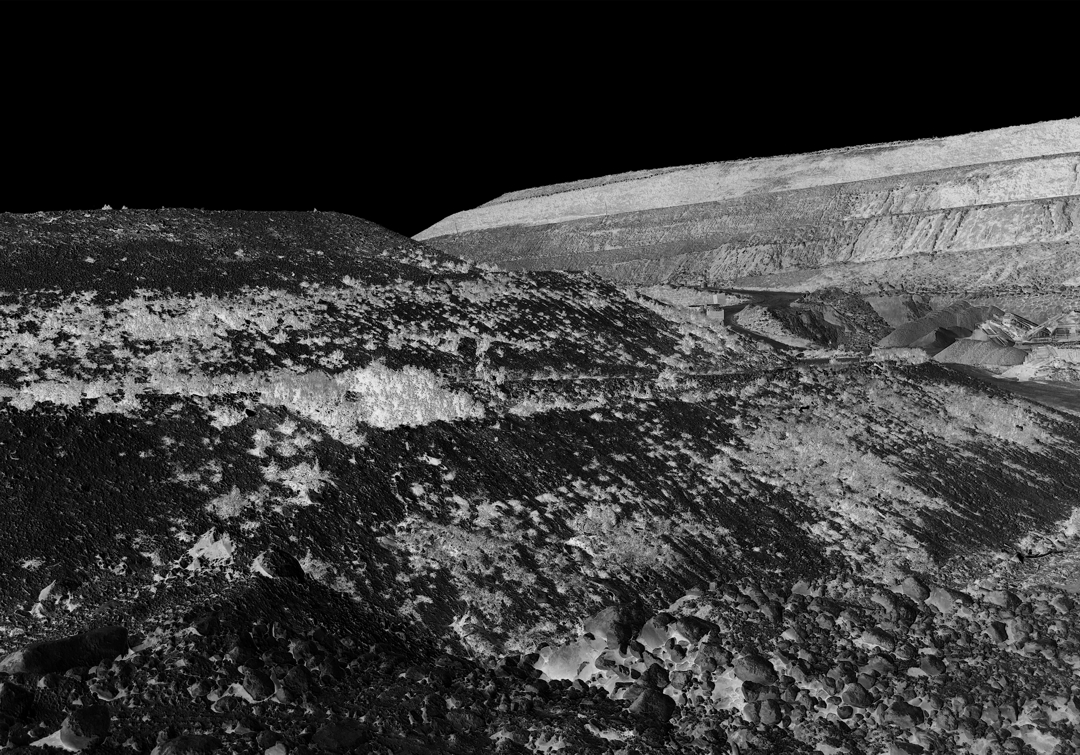

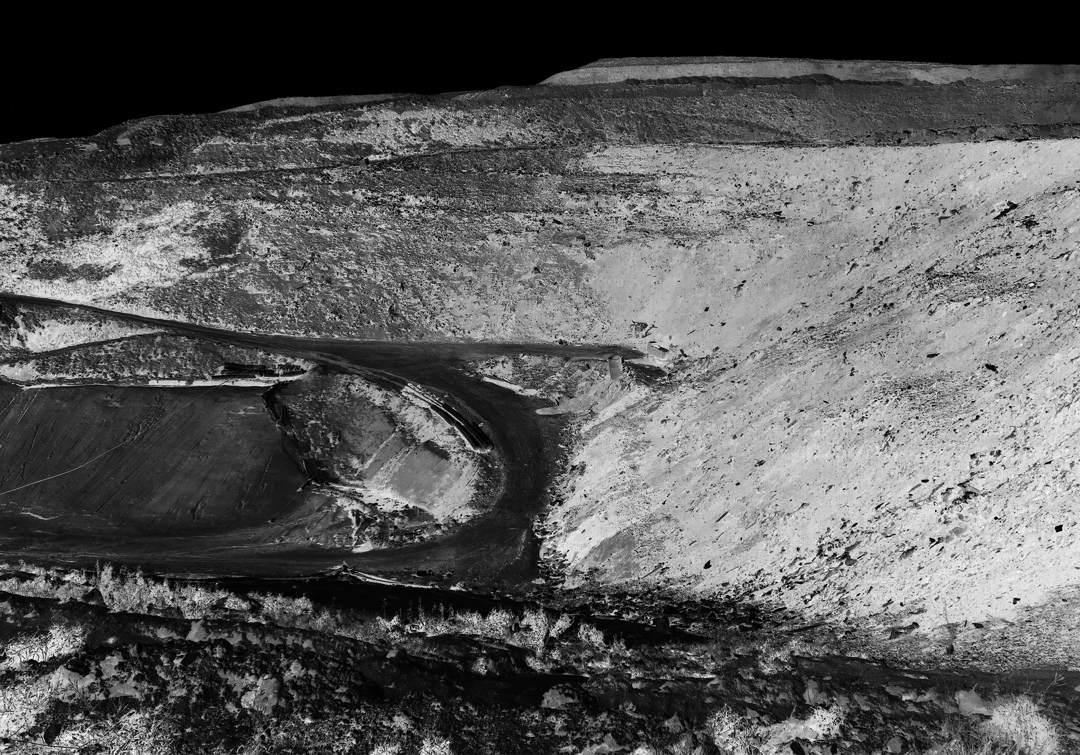

The imagery of the Magħtab Environmental Complex featuring in this exhibition resembles a lunarscape—a rugged, barren outline of a valley turned into a mountain of trash. Although the artworks expose the consequences of an economy based on mass consumption, the imagery is nevertheless strikingly beautiful. Ecological crisis can indeed be photogenic.

Right across the prints of Malta’s engineered landfill are images of Wied Għomor and the coast of Xgħajra, both earmarked for development. Viewed in that sequence, Magħtab’s lifeless sketch is a dystopian prophecy for the Għomor valley, which has been under threat of overbuilding for the past few years. It has been announced that the ruins of two houses in the valley, which were approved for rebuilding as two villas right before the 2017 election, are now on their way to becoming a 12-bedroom guesthouse.

The red-green palette of the prints is a flashing alarm bell, calling for our attention. Placed side-by-side with the blue-toned print of the sea off the Xgħajra coast, the colours allude to the bi-partisan consensus to give the green light to more ecological destruction of the country.

The most notable work, however, is the one the exhibition takes its name from—the ‘National Anthem’ triptych. On the right panel, photographs of Tigné Point and Sliema are passing through metamorphosis: they slowly break apart and dissolve into noise and which in turn merges with the surrounding sea. The central panel has the Maltese flag first dispersed into a spectrum of colours and then blended into a disturbed sea surface. The final, left panel depicts a series of horizontal strips of a noisy background. Is it sea surface? Or is it just noise? Is it construction noise or is it media noise in a country consumed by a storm in a teacup every week, hence unable to tell momentous events from trivial ones?

Either way, there could not have been a more accurate representation of a contemporary national anthem. Unarguably, noise is Malta’s national anthem in 2019. Also, it is no coincidence that noisy graphics blend so well with the imagery of the sea—the rising seas are on their way to reclaim their part of the Maltese coast, just as will happen in other parts of the world—that is, unless global capitalism, the rule of the golden passport buyers, is brought to an end in the coming few years.

Leave a Reply