In spite of the unprecedented political crisis, Joseph Muscat remained what a tattoo on his right bicep purportedly states: Invictus. He resigned on his own terms—bizarre outcome, considering the severity of the allegations implicating him in the Caruana Galizia murder cover up. We cannot fully comprehend it without finding out what sustained his baffling popularity.

by Raisa Galea

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]or better or for worse, the legacy of the last six weeks of 2019 will certainly become imprinted in our collective memory: amid a continuous stream of appalling revelations, the once-unshakeable authority of Joseph Muscat’s administration began to crumble like a house of cards. Or so it seemed. For a brief moment, the former prime minister was on the brink of an abyss, never before so close to falling from grace. Yet, despite the demands for his immediate resignation chanted by thousands of protesters in Valletta and the pressure of the European community, he left his seat of power on a high note—on his own terms.

In spite of the unprecedented political crisis, Joseph Muscat remained what a tattoo on his right bicep purportedly states: Invictus. Considering the severity of the allegations implicating him—the middleman’s testimonies claimed involvement of his former chief of staff Keith Schembri and “Kenneth from Castille” in the murder plot—this outcome is beyond bizarre.

The Daphne Caruana Galizia murder trial has set a decisive precedent: for the very first time, accomplices in a political murder have been identified and brought to justice. The shocking extent of impunity was laid bare for all to see. We learned that the murderers planned the crime in cold blood, expecting to get away with it (“Aren’t these like the Maltese police? Don’t worry” Fenech notoriously told Theuma in response to the latter’s concerns over the FBI getting on board). They fully relied on the inaction of their loyal appointees, convinced of their influence over police investigations and the judiciary as a guarantee against prosecution.

The Daphne Caruana Galizia murder trial has set a decisive precedent: for the very first time, accomplices in a political murder have been identified and brought to justice.

The murder trial is also a pivotal test for democracy in Malta. At its very core, this is a probe into whether or not members of the ruling elite can get away with crime. On the one hand, charges against Yorgen Fenech, a mighty tycoon, undermined the idea that the powerful stand above the law—a dent to impunity that can’t be overlooked. However, this landmark development was incomplete. The fact that the prime minister did not resign immediately under public pressure sent a different message: grave abuses of power can go on as long as the majority allows it.

According to a survey conducted by MaltaToday in December, the majority (58%* of respondents) were either content with Joseph Muscat’s delayed resignation or believed he should have carried on. Only a small fraction (2.8%**) of PL voters thought that the prime minister who was later named as ‘2019 man of the year in organised crime and corruption’ must step down immediately. We cannot fully comprehend this outcome without finding out what sustained his baffling popularity.

A Battle for National Pride and Identity

At its essence, Maltese politics revolves around the topic of national identity. Looking back at the most memorable debates of the past few years, we can note that all of them—from the economy, the Great Siege monument strife and LGBTIQ rights to spring hunting, Valletta2018 jablo sculptures and even Benna rebranding—were framed from the standpoint of national identity. Practically every subject debated in Malta is a quest for national pride. Even the European Parliament elections were characterized by the slogans “Malta f’Qalbna” and “Flimkien għal Pajjiżna”, despite the fact that Maltese patriotism is nowhere on the EP’s agenda.

Every development in this post-colonial island state seems to be a reason to ask: “Can we be proud of it as a nation?” However, there is rarely any consensus on this question since the views on national identity and pride are diverse and fall into two major—antagonistic—categories. Let us define these contrasting notions as ‘authentic folk’ nationalism and Eurocentric nationalism.

Exponents of ‘authentic folk’ nationalism are Maltese-speaking, proud-to-be-Maltese people predominantly of lower social standing. They express vocal pride in the achievements of the young independent state and slam criticism of its shortcomings as a deliberate undermining of Malta. They seem to hold that Malta already deserves to be on par with the rest of Europe and thus should not allow external interference into its seemingly internal affairs. Consequently, proud patriots identifying with this kind of nationalism support spring hunting (as a tradition forming part of Maltese identity) and gloat over the persistent wiping out of the Caruana Galizia memorial. After all, the slain journalist mocked everything they stand for, which makes her an alien and a traitor in their eyes.

To the ‘authentic Maltese folk’, national pride is the ultimate virtue.

Combining the results of two surveys—the one that established a significant support for Joseph Muscat’s resignation terms and the other which confirmed that “half of Malta believes” he could potentially be involved in the murder cover up—we can conclude that some segments of the population do not regard gravely unlawful behavior and remaining a leader, at least temporarily, as incompatible. To the ‘authentic Maltese folk’, national pride is the ultimate virtue. Being a proud Maltese alone appears to be enough to absolve of any crime while, by the same measure, deviation from this norm or being of foreign origin is perceived as almost a crime in itself.

In opposition to the proud-to-be-Maltese folk stand people whose national pride sounds rather hesitant. This group considers Malta inferior to ‘more civilised and democratically developed’ European societies. Contrary to the content patriots, these often Anglophone, profoundly Eurocentric representatives of the upper middle class claim that Malta is not a ‘normal country’ and has no chance to reach that level without continuous supervision from the European Union.

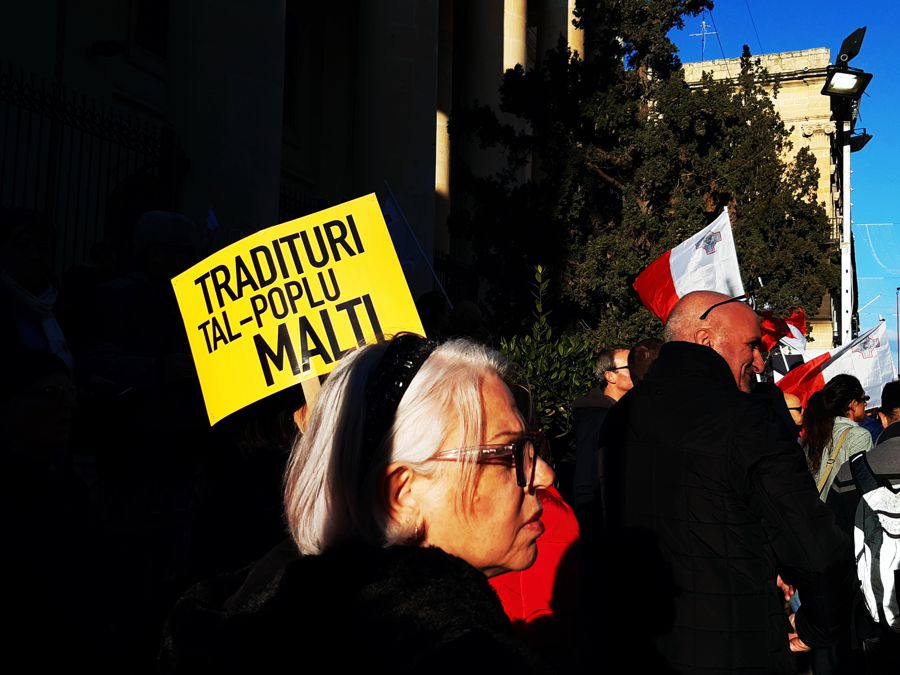

Despite classifying Malta as lagging behind ‘civilised’ Europe, the Eurocentric Maltese are no less patriotic than the ‘authentic’ ones. They, too, bring national flags to the protests. They sing the anthem. They, too, call their opponents ‘tradituri tal-poplu Malti’. Undoubtedly, both crowds gathered on the streets on December 2—the one to block parliament in Valletta and the other outside the Labour Party headquarters in Ħamrun—were inspired by the ‘love of their country’, each taking the other for a bunch of national enemies and traitors.

In a nutshell, the standoff between the government and civil society during the last few weeks of 2019 has been a contest in patriotism. To draw another parallel, the camps invoke the defining slogans of the 2016 presidential election in the United States, paraphrased. It is “Make Malta great” vs “Malta is already great”. But unlike a declining empire where the former catchphrase wins elections, a tiny former colony responds more to the latter.

The outcome of the referendum on spring hunting in 2015 was not only a sad day for migrant bird conservation. It announced a winner in a contest for national identity and pride. ‘Authentic folk’ national identity and unabashed pride in being Maltese calls the shots—and no one in present-day Maltese politics excels at igniting it better than Joseph Muscat.

The Leader Who Made the Nation Proud

“People say he’s corrupt, but I think he’s a good leader”, a new acquaintance told me on an occasion once the conversation turned political. “He has an ambitious vision for Malta, he thinks big. I’m proud of my country more than before”. This conversation confirmed my hypothesis on the strategy behind Joseph Muscat’s popularity: boosting national pride and the ego of an average Maltese person. Staying firm under international pressure was a key ingredient in achieving this effect.

Joseph Muscat tapped into patriotic sentiments already a few years before he was elected as prime minister. Delivering a speech in Maltese at the European Parliament’s plenary session, he suddenly paused and then refused to continue after having realised that translation was unavailable. In a visibly emotional manner, he declared: “No way, you either give us really our language or ‘thank you and goodbye!” From a national pride standpoint, this was broadly interpreted as an admirable act of patriotism, while others—Daphne Caruana Galizia among them—ridiculed it as a sign of his poor command of the English language. “I’m with the nationalist party and even then I respect what Dr. Muscat did here” reads a comment on a YouTube page of the recording.

The strategy behind Joseph Muscat’s popularity was boosting national pride and the ego of an average Maltese person. Staying firm under international pressure was a key ingredient in achieving this effect.

Legalisation of same-sex marriage in a country with dominant conservative social values, only a few years after the divorce referendum was an ambitious move for Muscat’s administration. He found a winning strategy, however, permitting to appease the LGBTIQ lobby while retaining popular support: anyone whose religious sentiments were hurt by the development could be amply compensated with national pride. “We made history”—the rainbow message projected onto Castille rendered Malta a champion of the cause in the European Union. Since 2016, the country has been ranked the most progressive in Europe for ‘gay rights’.

National pride had another glorious moment in 2017, when Muscat took the prime ministers of Belgium, Luxembourg and Slovenia for pastizzi at Serkin. What could possibly declare a leader more patriotic than introducing fellow European leaders to staple food ingrained in national identity? There, he presented himself as a true man of the people, down to earth yet ambitious—an image every ordinary Maltese of any partisan leaning could aspire to.

Enjoying traditional #Malta pastizzi snack with #Belgium #Luxembourg #Slovenia PMs @CharlesMichel @Xavier_Bettel @MiroCerar and partners -JM pic.twitter.com/zFbjaaQ8Bu

— Joseph Muscat (@JosephMuscat_JM) February 4, 2017

Judging by the examples of Putin, Orbán, Erdoğan and, above all, Trump, domineering rulers are more successful at invoking national pride. ‘True patriots’ in power bulldoze over opponents, lest a willingness to compromise be perceived as weakness by proud citizens. Having declared his pride in being Maltese and keeping the country’s best interests at heart, Joseph Muscat scored more political points when he ignored international pressure.

Perhaps the boldest geopolitical move by Muscat in recent years was his uncompromising take on the humanitarian crisis and Mediterranean rescue missions. He was the one to call for stricter EU border security and the relocation of migrants from Malta. Speaking to national media, he also continuously emphasised that migrants taken in to Malta were indeed being transferred to other member states.

Malta’s objection to rescue vessels’ disembarkation for more than two weeks in January and April 2019 pressured the EU to step up the game and enter redistribution agreements. Former Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi publicly honoured Muscat for leadership skills and “solving the European migration crisis”—something that neither Giuseppe Conte nor Matteo Salvini were capable of. This stance must have made the patriotic heart beat with even more pride: there was a strong leader, a Maltese man who defended the country from ‘invasion’ and made the foreign counterparts respect his decision.

One of Muscat’s favourite strategies was to present economic growth as a prime source of national pride—and his own chief accomplishment.

One of Muscat’s favourite strategies was to present economic growth as a prime source of national pride—and his own chief accomplishment. Even in a political climate where everything is discussed from the standpoint of national identity, selling the economy as the whole country’s success requires extra imagination. Why would segments of the population left behind by the booming economy—single mothers, pensioners and low income earners—feel proud of the economic setup that does not benefit them?

Considering that Malta’s economic miracle was sustained by underpaid migrant workers and the budget surplus was abetted by passport sales, one could expect that patriotic feelings of the majority would be hurt, not boosted. However, this is where the political genius of the former prime minister lies: he grasped that just about anything could be branded as national triumph if peppered with flashy nationalistic rhetoric and served by a strong uncompromising leader.

Even in his televised speeches and final remarks, Joseph Muscat remained true to the image of being his country’s most loyal servant. Announcing his resignation, he pledged the citizens to take pride in the young republic’s achievements. A glamorous version of the Maltese national anthem played in the background, intensifying these sentiments: it alluded to the progress of the post-colonial island state that has become modernised and is now a salient player on the world’s stage. “We have to continue dreaming, because when the PL created solutions, the country won”, he stated in his final speech as prime minister.

Even Muscat’s resignation was orchestrated in line with ‘authentic’ national identity and traditions. Instead of explaining his decision as acting according to democratic principles and assuming responsibility for implications in institutional murder cover up, he presented his exit as a sacrifice—a concept many devoted Catholics could sympathise with. There stood a father of the nation—a ruler whose trademark was keeping firm under external pressure—who had to sacrifice his career on the altar of the nation’s ‘happiness, love and positivity’. A country’s patron saint, with no exaggeration.

Instead of explaining his decision as acting according to democratic principles and assuming responsibility for implications in institutional murder cover up, Muscat presented his exit as a sacrifice—a concept many devoted Catholics could sympathise with.

Thus, it comes as no surprise that the majority of Maltese citizens would still see Joseph Muscat as a leader they could be proud of, despite fierce international criticism. In the eyes of proud nationals, a true patriot of his country would always be disliked by outsiders. The fact that the Eurocentric crowd regarded his postponed resignation and the infamous ‘award’ in organised crime and corruption as a national tragedy must have only confirmed the views of the proud-to-be-Maltese. In a context of antagonistic notions of national identity, what is a tragedy for one is a triumph for the other and vice versa.

Next: Finding a Common Ground for Maltese Nationalism and Calling for National Unity

Robert Abela succeeding as the new Labour Party leader and the new prime minister proves that the brand of Joseph Muscat remains largely appealing to the PL base. Standing behind Muscat ‘until the last moment’, imitating his domineering body language, the emphasis on continuity with his predecessor and being the least preferred candidate for the Eurocentric non-Labourite lobby must have all played a role in winning the leadership race with a wide margin.

While the other candidate Chris Fearne placed partisan pride above the national one (“Kburi li Laburist, kburi li Malti”) and openly stirred partisan controversy in his campaign, Abela’s partisanship was present yet more discreet. He positioned himself as a leader capable of ‘uniting the nation’, which echoed the pledges of the President George Vella. In his first public comments, the newly elected leader called for national unity, implying that the two contrasting approaches to national identity and pride must somehow come together.

How can such antagonistic perspectives unite? The most important question, however, is who is to benefit most from this unity?

Above all, national unity means uniformity and lack of dissent, which then implies that one of the opposing camps must be assimilated by the other. Given that adamant pride in being Maltese seems to be preferred by the majority, compared to self-deprecation and not-a-normal-country lamentations, it is easy to guess which narrative is to assume its formal status. In this case, criticism of the government would be discouraged and labelled as treason against the nation.

Another predictable strategy of the new prime minister could be to unite ‘the nation’ in opposition to non-Maltese residents, particularly non-European others. Robert Abela’s promise “to better regulate foreign workers” hints at this possibility. Since clamping down on a number of foreign workers is not beneficial for entreprises profiting from them, the pro-business government could further restrict the workers’ legal status to what it desires them to be—servants to the economy whose fruits is for the natives to enjoy.

Another predictable strategy of the new prime minister could be to unite ‘the nation’ in opposition to non-Maltese residents, particularly non-European others.

Either way, Joseph Muscat’s ‘glorious’ exit and the Labour grassroots preference for ‘continuity’ rather than change are no reason for rejoicing in democratic optimism. They decimate the likelihood of constitutional reforms and of holding the powerful to account.

Ultimately, the outcome of the political crisis proves that members of the ruling elite in Malta can, indeed, still get away with crime if the majority allows it. This is a victory for the status quo and the establishment, eager to blatantly discriminate against non-Maltese residents and all those who deviate from the prevalent brand of national identity in order to retain power at all cost.

*The total of 58% of respondents did not insist on Muscat’s immediate resignation: 43.2% agreed with Joseph Muscat’s resignation terms and 26.4% of 58.6% of those who disagreed said he should have carried on.

** 4.5% of 63.5% of PL voters who did not accept Muscat’s resignation terms.

Leave a Reply