In the 19th century, new social practices, such as the promenading up and down the streets, mainly by men, reflected a new economic reality. Streets proved to be the right passages as architectural commodities for a capitalist economy rooted in visualism. The body became an artefact of display, which demanded the gaze of the onlooker.

by Rachael Scicluna

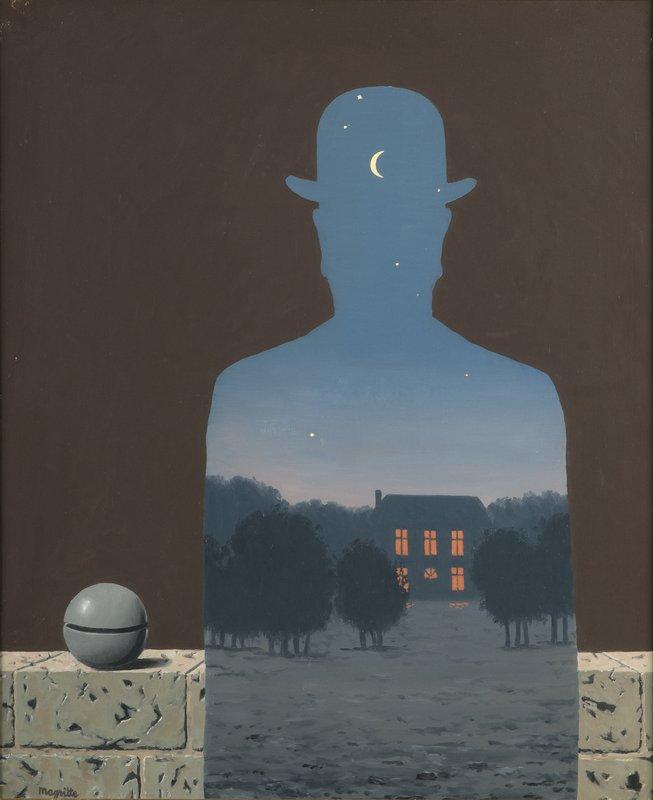

Collage by the IotL Magazine (after René Magritte)

The street is an everyday site of geographical knowledge and leisure practice. In recent geographical literature, there is the impression that the street is spectacle, display and epitomised in the gaze, the flaneur.

David Crouch

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]treets as sexualised and gendered spaces have a Western history of their own, like any other social space. In his book “Images of the Street: Planning, Identity, and Control in Public Space“, the British architectural historian Nicholas R. Fyfe reminds us that streets have held “a particular fascination for those interested in the city.” They come to life through social interaction, and it is exactly these social encounters which have concerned rulers.

For centuries streets have been sites of political protest, domination and resistance, and places of pleasure and anxiety. Thus, social control disguised under strategic urban planning and designs of streets have been implemented in order to accomplish safety, control and surveillance. This understanding of the street is also accompanied by a capitalist ideology, where the city has been compared to a sick organism and the planner to a surgeon opening up the clogged arteries (in the words of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the renovator of Paris). These medical undertones are not unimportant, since we can see how the body is moving toward centre stage and becoming the focus of social order and efficiency.

The imagery of an efficient bodily circulatory flow comes to represent an efficient urban system. This also has economic implications. The boulevard, apart from securing the city from civil wars, had an important economic function. The smoothness it provided paralleled the quickened pace of commerce. The construction of the boulevard further employed a large number of working class individuals while it pushed them out of the streets to the periphery of the city. Furthermore, it “symbolically […] provided an unequivocal demonstration of the power of the state to shape the urban landscape in the interests of the bourgeoisie”.

The smoothness the boulevard provided paralleled the quickened pace of commerce. The construction of the boulevard further employed a large number of working class individuals while it pushed them out of the streets to the periphery of the city.

This modernist understanding of the street had an influential impact on the architect and planner Le Corbusier and the ideology he employed behind his ‘new kinds of streets’ planned in the early nineteenth century. For him the “corridor street should be tolerated no longer because it is full of noise and dust, deprived of light and so poisons the houses that border it [my emphasis]”. Even though the luring rhetoric of city as machine sounds attractive, such urban planning removes the ontological experience of how individuals experience social encounters in the streets. As Fyfe highlights, the street needs to be:

‘multifunctional’, not the exclusive domain of traffic, and for there to be ‘eyes on the street’ belonging to local inhabitants and traders who are able to provide neighbourhood surveillance of activities taking place on the street [my emphasis].

This brief historical overview of the birth of the modern street as we experience it nowadays has limitations, as it only considers an understanding of streets in a Western context. Furthermore, this history mainly belongs to the experience of the affluent heterosexual male. Other types of streets in different locations both in the West and outside may contribute toward a larger understanding of how streets are experienced in the everyday life of inhabitants.

More experience from the homeless, squatters, disabled, the very young and old, non-heterosexual individuals should be included to add to the multiple experiential sphere of such a space. These experiences are instrumental in understanding the meaning of our homes even further. Houses are at the borders of streets. Thus, the codes of ethics, type of street and neighbourhood may have an impact on the way the “private” domain of the domestic unit is experienced.

Streets as Symbols of Lifestyle

Streets are not culturally innocent public places. As Jon Binnie and David Bell observed, streets embody cultural and local knowledge and they “are symbols of an attitude to life.” For instance, the rise of a leisure practice demanded a civil society which was ready to embrace spectacle and display as part of the everyday. In the early nineteenth century, the streets of London seem to have been the ideal material sites for a capitalist ideology to flourish.

New social practices, such as the promenading up and down the streets, mainly by men, allowed for a capitalist economy to root itself in the gaze. The idea of ‘the gaze’ and the spectacle during this period further illustrates the processual ideological shift toward panopticism, as French philosopher Michel Foucault defined it. Thus, streets proved to be the right passages as geographical and architectural commodities for a capitalist economy to root itself in visualism. Furthermore, the body like the street (and the house) became an artefact of display, which demanded the gaze of the onlooker*.

Streets as Social and Political Spaces

Modernists tend to associate streets with a linear destination and a flow of movement spatially split for: pedestrians and vehicles; the exchange of goods and people; zones of trade and commerce; administration and entertainment. This modernist concept embodies a capitalist ideology, which replaces the ‘waste and inefficiency of the rue corridor’ and that of the traditional slow paced street. However, this linearity of time and destination leaves out a crucial aspect of what makes a society—people.

As the geographer Yi-fu Tuan notes, “the modern architectural environment may cater to the eye, but it often lacks the pungent personality that varied and pleasant odours can give” [my emphasis]. This illustration is vivid enough to elicit memories of places through our senses. It highlights the phenomenology of existential existence in its everyday. It is very common for people to associate a place with a smell, or to bring a token as a remembrance of a particular place. This is a cognitive mechanism which people embark on as an aid to memory, and has the capability to instil meaning and value to a place. Hence, spaces need the interactive movement of inchoate characters and objects to become a place.

Through a historical process of civilisation and culture, social actors have had the capability of turning a space into a place, and a house into a home. This capability is part of a processual interactive path. This interactive path should not be thought of being linear, but should be conceptualised as a winding flow like that of a river, always in flux, where the water flow depends on many outer environmental factors—wind, rain, global warming, fishing, houses built nearby, fields nearby, the animals grazing and drinking from it, the construction of dams, and so forth.

A simple process of walking along the streets is indeed a ‘complex political act’. It is embedded in a ‘complex path’ which dates back to a long history of civilisation, and to an existential present of being-in-the-world.

As the British anthropologist Tim Ingold highlights, “every place is like a knot tied from the multiple and interlaced strands of growth and movement of its inhabitants, rather than a hub in a static network of connectors.” Through learned bodily habits and their performance, which embody the habitus, walking along the street becomes a political act which starts inside the home. It is a path that in its interactive movement interweaves the private and the public, mainly through the engagement of the body with place.

This simple process of walking along the streets is indeed a ‘complex political act’ and embodies a ‘complex whole’—that of culture and civilisation**. Thus, if we look closer at the simple act of walking we come to realise that it is embedded in a ‘complex path’ which dates back to a long history of civilisation, and to an existential present of being-in-the-world. The existential side of this ‘complex path’ is what allows for a creative endeavour with the environment (all surroundings including all animate beings and inanimate objects).

Intimate Life and Public Spaces

Before embarking out on a public path an individual goes through certain preparatory physical and psycho-social rituals. Firstly, an individual goes through an intrapersonal dialogue of considering the idea of going out. Secondly, they engage in a ritual of preparing the self and body to be outside, starting from: grooming, dressing up to preparing one’s bag with basic material objects such as a purse, mobile, and home keys which are essential when out in the world of shopping, work, attending religious rituals or meeting with family and friends. This interactive path is a process which starts in the domestic unit and is carried out in public or semi-public places.

Of course, this scenario depicts a very basic ritual and I am aware that this process is not as linear and clear as I portray it to be. Every individual will have a variety of ways for preparing to be out in the street (or any public domain). For example, the phone might ring before an individual is going out which might or might not disrupt this ritual and, may or may not, cause delays or a change of path. It is exactly this ‘chaos and fuzziness of life’ which makes this path an interactive movement which is always in the process of becoming.

At this point, I want to turn my attention once again to ‘the home’. I want to illustrate how homes and streets have a mutual influence on each other, and this is brought together through the body via this interactive path. Streets cannot exist without homes, and homes cannot exist without streets. This intersectionality of the domestic unit with the public domain shows how the home is influenced by variable factors apart from the hegemonic ideology of the state. The concept of a place “as open and porous” is useful as it draws in it social movement and different flows of power coming from different spheres of life.

Therefore, home plays an important part in the presentation of the self as spectacle in the public domain. Streets like the inchoate self are always in flux, changing with the needs of new social practices and customs, with new impacts of technology and new architectural concepts. The concept of the street as spectacle finds its roots in the early nineteenth century when London was developing into an important site of leisure and consumption. In order to meet this urban need, a social practice based on pleasure derived from looking, new urban designs had to be created for public display.

Jane Rendell states that “place of leisure in the nineteenth-century city represent and control the status of men and women as spectators and as objects of sight in public arenas.” Thus, we see the rise of architectural spaces such as the promenade which enhanced bodily display. Marxist critical thinkers state that the transformation of public spaces were almost analogous to commodity fetishism and “to the increasing emphasis on visual exchange rather than tactile stimulation”.

Thus, new urban spaces arose, such as the theatre, arcades and parks to fit this new urban cultural need. Streets such as Regent Street in London, were part of this new major planning and their improvement facilitated mobility and at the same time “provided a social space for visual display and consumption [my emphasis]”.

Fashion and dress as a social ritual was part of this new urban culture. This was part of a process that initiated a new set of activities in the life of the rambler like the flaneur, such as parading “up and down St. James’s Street and Pall Mall in order to display body and possession.”

Fashion and dress as a social ritual was part of this new urban culture. Rendell notes that this was part of a process that initiated a new set of activities in the life of the rambler like the flaneur, such as parading “up and down St. James’s Street and Pall Mall in order to display body and possession.” What is interesting is that within this period these streets became a space of male urban fashion, mainly of the urban rambler who articulated “his masculinity through dress and language codes, and through various kinds of spatialised social activities”. This suggests that the commodification of the street was part of a new social process/ritual in the making of spectacle. As Rendell states “the street played an integral part in producing a public display of heterosexual, upper class masculinity.”*** This public display asked for particular ways of walking, talking and dressing. Here, the viewer becomes as important as the viewed.

At this stage it is also important to highlight how urban designs had ulterior motifs too. Urban design and architecture (think of Bentham’s Panoptic) have the ability to systematise and categorise bodies and flow of movement. Here it is worth quoting Jane Rendell at length:

Architecture controls and limits physical movement and sight lines; it can stage and frame those who inhabit its spaces, by creating contrasting scales, screening and lighting […]. Such devices are culturally determined, they prioritise certain activities and persons, and obscure others according to class, race and gender. Urban space is a medium in which functional visual requirements and imagery are constituted and represented as part of a patriarchal and capitalist ideology. The places of leisure in the nineteenth century city represent and control the status of men and women as spectators and as objects of sight in public arenas.

However, as David Crouch notes “we are not only flaneurs” and objects of capitalist desire. We create knowledge and embody the street. As the feminist anthropologist Judith Okely states, we are embodied beings and are able ‘to see’ and receive information through our senses, and engage with it. So far, I have highlighted how the body, the home and street become objects of desire through spectacle, which has strong connotations to ‘being watched’. It further illustrates a shared social practice based on wider social norms and values of how to present ‘the social body’ within shared places. Within this analytical framework the image of the body and the street becomes a rhetoric of post-modern reality based on the ‘voyeuristic gaze’.

This type of creative engagement with ordered space comes out clearly in Gill Valentine’s examination of the interrelationship between the street and food. Gill Valentine explains how historically streets carried social expectations about public eating which was considered to be a civilised space:

where people exercise self-restraint in the face of natural urges to eat; a public space where intimate, ‘private’ bodily matters such as eating are not on display; and an ordered space, where the mess of consumption is kept out of sight.

This social restraint on the civilised body is yet another act of surveillance based on visual display. Valentine illustrates how attitudes and codes of behaviour are changing due to how ‘time’ is conceptualised in contemporary urban life. Eating in public is becoming more acceptable, even more so since fast-food branches offer take-out meals which can be consumed during limited working lunch hours. This suggests that this type of engagement with street customs follows a social and an economic need that requires efficiency.

Eating while walking illustrates a new kind of street-disposition. This resonates with a capitalist ethos and comes to stand for a future investment (related to work and money) and not a waste.

Efficiency embodies the concept of Time which is associated with production. It is a modern industrialised concept which structures the imponderabilia of everyday practices which correspond to the way we act in relation to time. Time is a valuable commodity which shapes and describes our experiences accordingly. Thus, the informality of the street that Valentine mentions is not simply a movement forward toward democracy and a less regulated space. Eating while walking illustrates a new kind of street-disposition. This resonates with a capitalist ethos and comes to stand for a future investment (related to work and money) and not a waste.

Time becomes the new ‘eye of surveillance’ practiced in the streets. This whole concept is part of a historical process that finds its feet in the panoptic principle. The Panopticon was not a mere architectural invention but “an event in the history of the human mind”.

* For example, during the 1980s home owners in the UK tried to differentiate their external house facades from those of their neighbours’ rental homes. This was stimulated by the “’right to buy’ housing policy of Britain’s Conservatitve Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher”. It is fascinating to see how a house façade is used as a symbol of social hierarchy. It becomes a symbolic and political act which demands the attention of the onlooker. It is spectacle.

** This is a key concept in anthropology. English anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor defined culture as “that complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society”.

***Jane Rendell brings to our attention the meaning of the verb to ramble which is “the exploration of urban space. Rambling is ‘a walk without any definite route’, an unrestrained, random and distracted mode of movement. As an activity, rambling is concerned with the physical and conceptual pursuit of pleasure, specifically sexual pleasure—‘to go about in search of sex’ (see Oxford English Dictionary; Partridge, 1984). The rambler traverses the city, looking in its open and in its interior spaces for adventure and entertainment; in so doing, he creates a kind of conceptual and physical map of what the city is. Rambling rethinks the city as a series of spaces of flows of movement rather than discrete architectural elements.”

Leave a Reply