Governments, present and future, should be obliged to act on the declared climate emergency and the ecological crisis facing us, which is an emergency indeed.

by Miguel Azzopardi

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the 2019 budget, the government announced that the country aims to decarbonise by 2050. A week later, parliament even declared a climate emergency. Following these announcements, of course, concrete actions would urgently need to be planned and implemented. In this spirit, this article proposes some suggestions on how the climate crisis could be tackled.

Decarbonising by 2050 could be too late to avoid a climate catastrophe. The Maltese archipelago is, indeed, already experiencing tangible effects of climate change—drought is one such example. Thus, further delaying climate action risks increasing these effects to the extent of them becoming significantly more frequent and severe. We should be aiming to decarbonise by 2030, not 2050.

If this target sounds ambitious, that’s because it is. There are three principal obstacles to achieving this, each corresponding to the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Malta: energy, transport, and shipping and aviation. In tackling the main pollutants, Malta’s carbonour footprint can significantly be reduced. While achieving decarbonisation by 2030 will be difficult, I nonetheless think that it is possible in principle—if there is a real political will to achieve it.

Legally Binding Targets

The first step, then, would be to commit to carbon neutrality. In the declaration of a climate emergency and the announcement of the intention to decarbonise by 2050 the government has made significant steps. But we need to go at least one step further. The current commitment to decarbonisation should be made legally binding to ensure decarbonisation is achieved by an agreed date, and this should be sooner than the 2050 date proposed. In that way governments, present and future, would be obliged to act on the declared climate emergency and the ecological crisis facing us, which is an emergency indeed.

Governments, present and future, would be obliged to act on the declared climate emergency and the ecological crisis facing us, which is an emergency indeed.

Words, thus, must be followed by actions. The root causes of climate change must be addressed: those major sources of greenhouse gas emissions mentioned.

Decarbonising Energy Supply

Despite the use of the interconnector linking Malta’s grid to Sicily, our energy supply is still heavily dependent on the power plant at Delimara. While definitely an improvement from the previous Marsa power plant, this is still a power source that emits greenhouse gases.

Recent efforts to encourage renewable energy, solar power specifically, are steps in the right direction, but they have not achieved the desired results. Renewable energy sources still account for less than 10% of the energy mix and it seems unlikely that Malta will meet its self-imposed EU target by 2020.

A transition to renewable energy sources would require more than an increase in the installation of solar panels but it would mean investing in other energy sources as well, such as wind power.

But how can this be done quickly and with the limited space that we have? There are already a number of solar farms in the pipeline, but they either are not yet in operation or have not made a significant impact. Locating some of the renewable energy installations offshore—especially wind power installations—is one possible solution as it would prevent them from unnecessarily taking up vast plots of land.

The construction boom and the lack of urban planning impede the development of solar infrastructure. Homeowners may be reluctant to invest in PV panels due to the possibility of being shaded by a newly constructed apartment block nearby.

More incentives could also be provided for people to install solar panels on their private houses. Not only would such projects help achieve the decarbonisation goal quicker, they would also ensure that energy supply is decentralised and democratically owned. Since many households may not be able to afford the installation of PV panels, this initiative would require state support. It may even be possible for Malta to acquire EU funding for such a project, especially since the EU is looking particularly at dedicating a significant part of its budget for environmental and decarbonisation initiatives.

However, we must keep in mind that the construction boom and the lack of urban planning impede the development of solar infrastructure. Homeowners may be reluctant to invest in PV panels due to the possibility of being shaded by a newly constructed apartment block nearby. Thus, on top of contributing to air pollution, traffic jams and noise, the environmental costs of the building boom also include undermining the potential for a decentralised solar sector.

Decarbonising Shipping and Aviation

Addressing decarbonisation of shipping and aviation is trickier because any measures taken by the government cannot address all of the ships and planes coming to the islands. We can put pressure onto the international community to ensure more stringent standards and call for an end to the use of heavy fuel oil.

There should also be more pressure on the aviation industry to adopt more fuel-efficient technologies and invest in the development of technologies that might allow their operations to run without causing significant greenhouse gas emissions, even though that seems a rather unlikely scenario in the near future. With Malta’s considerable maritime and aviation registers, and as a member of the European Union, we have a voice on this issue, and we should use that voice to lobby for change.

While there is little we can implement overseas, we can and should take more direct action with regard to transportation locally.

Decarbonising National Transport

But how would we go about changing our transportation model?

The government has recently announced its plans to shift to electric cars. While this could seem like an environmentally-conscious move, the shift to electric vehicles must be accompanied by other steps. Individual electric transport does not solve the problem of emissions, it simply shifts the source of emissions from car engines to power plants, meaning that power plants, renewable or carbon-reliant, must generate more electricity to cater for electric vehicles.

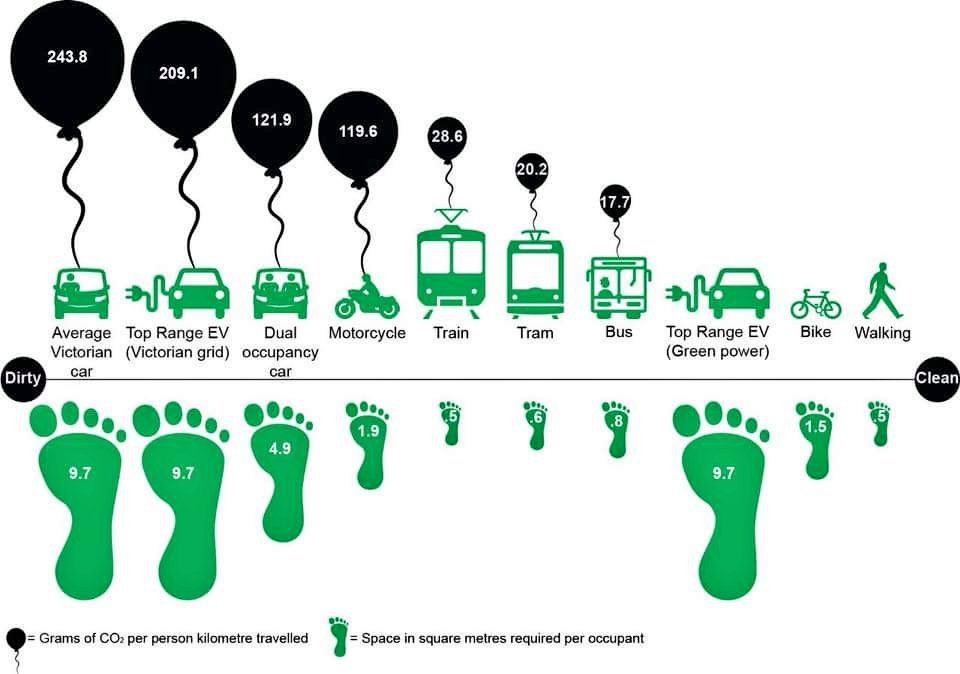

Instead of the current road-widening projects, we should push for a green transport strategy that prioritises cyclists, pedestrians, public transport, and micro-mobility users over cars. This would also be a better use of space, which is a resource, too, and on an archipelago like Malta, we need to be especially careful how we use it. Using space more effectively would also make room for other environmental projects.

The strategy of reducing traffic through road-widening is misguided because cars take up a significant amount of space when often they only have one or two people inside. If cyclists, pedestrians and public transport were given priority, we would be able to fit many more people into that same area. Such a shift in our transportation model would lead to needing far fewer natural resources and leaving a smaller environmental impact than by just changing the car fleet from petrol or diesel-powered to electric—not to mention the environmental impact of all the newly built electric cars and their batteries.

The government is currently working on improving the routes and frequency of the public transport system. In order to meet decarbonisation goals, public mobility options need to be diversified and improved; for example by introducing bus and bicycle lanes and safe pedestrian passageways. Adjusting our infrastructure can allow buses to avoid traffic and cyclists and pedestrians to feel and be more safe. Providing incentives such as reducing the cost of public transport or making it free would likewise convince more people to use it. All of these measures would encourage people to use alternative means of transport which combined would have a lower environmental impact.

Reforestation Projects

In addition to all of the proposals aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, we should also implement policies that will actively remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. One of the easiest ways to do this is to rehabilitate areas of abandoned land throughout our islands through rewilding or reforestation schemes.

Recent reports have suggested that the natural environment has an enormous capacity to absorb carbon, although the exact amount has been disputed. There is enough remaining open space that is not used for agricultural purposes that can be utilised for such projects. Cultivating greenery could have a double positive impact: restoring biodiversity while serving as carbon sinks. It would also restore much needed greenery to our islands. We should take every opportunity available to create carbon sinks as these are essential in reversing the effects of anthropogenic climate change.

By tackling some of the major sources of pollution, it may be possible to achieve carbon neutrality in a relatively short amount of time and much sooner than the 2050 deadline proposed by the government and the EU. Initiatives that can help take carbon out of the atmosphere would also help reduce man-made impact.

Addressing an unprecedented ecological crisis requires ambitious thought and solutions. In this process, I urge the government to engage more with the suggestions of NGOs who have a wealth of knowledge in some of these areas. It is time to turn words into actions.

Leave a Reply