Feminism needs ambition to achieve change, but for the sake of appearing ‘nice’ and non-threatening, activists have to dedicate much effort and emotional labour to soothing their critics’ fears.

by Daiva Repečkaitė

Collage by the IotL Magazine (based on a painting ‘Judith with the Head of Holofernes’ by Andrea Vaccaro, detail)

[dropcap]“[/dropcap]Gender equality is important, but contemporary feminism is over the top,” numerous people, mostly male-identified, have said to me directly or in overheard conversations. Some of these words come from spaces frequented by people who otherwise care about social justice.

What exactly is over the top, I ask, whenever I am part of that conversation. “It’s become all about hating men,” a few of them say. Who did you read, I ask, with curiosity I most often fake, because I know what I’ll hear next. “Oh, you know, in Facebook discussions…” they tell me, and fail to bring up a specific example.

No, I don’t know, so you need to tell me about it, because I’ve never met the kind of feminist you describe. The militant feminist who only cares about shaming and blaming is as much of a straw woman as the bra-burning feminist is for the older generations.

I’d love to talk to a bra-burning feminist one day, and I always ask older men who bring up feminism’s “image problem” whether they could introduce me to one. But this hasn’t happened, because bra-burning feminists are just so rare. And when I ask Maltese men to name at least one local feminist who, in their opinion, ‘hates’ men, the closest I’ve got to a name was a reference to some person who sometimes likes to be aggressive on social networks.

An Exaggerated Misled Impression

Many like it rough when it comes to discussions on Maltese politics—openly hostile exchanges are so common in the generally polarised discussion climate, I struggle to picture what this fictitious ‘militant feminist’ must have asserted to leave a lasting impression on a local.

What would I do if I ever met an actual flesh-and-blood militant feminist? First of all, I would read. I would read their Facebook—quietly, without commenting or reacting—and look up any published texts. I would ask questions. I would try to understand where they come from. Yet so far no one has introduced me to a local militant feminist.

I think, living here as a migrant worker for a few years, I have met more local feminists than most of the men who criticise them. I know deeply caring feminists, who go out of their way to help others. I know powerfully generous feminists, who share their time and resources with the community. I know disarmingly persuasive feminists, who advocate for the rights of people far outside their social bubble. But show me a local militant feminist because I’d like to experience the full spectrum. The islands are so small, and if one has the impression that militant feminists are everywhere, surely someone should be able to introduce me to one.

Show me a local militant feminist because I’d like to experience the full spectrum. The islands are so small, and if one has the impression that militant feminists are everywhere, surely someone should be able to introduce me to one.

“Well, maybe not on the islands, but abroad… The #MeToo movement… You know?” And again, I don’t know.

I know of occasional anger and frustration in individuals who are exhausted in their daily activism. I know of arguments that risk alienating certain sectors of society. Sometimes individuals use these arguments. When they do so, they are more likely to be quoted or retweeted. You are more likely to read them when they use these arguments, forgetting who exactly voiced them, and what they said before and after that. Some individuals who say insensitive things later apologise, but that’s not reposted much.

In a hyper-mediated society, many of these conversations turn into a steady buzz. A snappy tweet is enough to leave a lasting impression on someone, and coming across two similar arguments might lead to an exaggerated impression of the phenomenon. ‘A swarm of militant feminists descended on me’ is a narrative likely originating from a few unpleasant social media encounters.

Challenging the ‘Nice Girl’ Stereotype

Feminism is a movement mostly of, by and for women, and many women were brought up to be ‘nice’ at any cost. Cultural pressures leave individuals who vaguely ally with this movement open to pressures from conversations as described above.

“At school I am scared to call myself a feminist because it means I hate all men. But I love my boyfriend, I love my father, I love my grandfather… feminism is about equality,” said Laura, 17 years old at the time, speaking at a roundtable for MEP candidates and children. Her sentence perfectly encapsulates the most likely way a local feminist would speak: it starts with a reaction to the overall discourse, then goes on to profess distance from the straw woman attacked by critics, and then finally takes the liberty to make her point.

The people who pushed Laura to defend her values in these verbal trenches are confident that their opinion is just as valuable as someone’s knowledge and activism. Yes, these critics who drove Laura into a trench were confident, and they didn’t feel they needed to explain where they came from. But Laura did.

The pressure to constantly apologise, explain, and distance oneself from potential other, ‘bad’ or misunderstood feminists takes up a lot of time and space. It shrinks the already limited speaking slots and devours word counts that girls and women carve out for themselves to make their point.

The pressure to constantly apologise, explain, and distance oneself from potential other, ‘bad’ or misunderstood feminists takes up a lot of time and space.

Imagine if every elderly man serving in the government, business or academia had to spend this much time explaining that he is not going to enact stereotypes his audience may hold about his age. It would be a waste of everyone’s time. Yet it’s 2020 and numerous feminists still feel they have to prepare the ground for their argument by first explaining where they come from, and promising not to be that militant straw woman.

Militant Patriarchy in Practice

Feminists explain themselves while Malta sits in the lower half among the world’s countries when it comes to gender parity. Women die from past partners’ violence, and a man walks free after narrowly failing a rape attempt. The largest national newspaper dedicates an article to gossip blurted by a child rape victim’s relatives defending the suspect (later convicted), and goes on to inform readers, without any context, that domestic violence victims, many too terrified to continue with their charges, waste judges’ precious time. Following this prompt, a reader commented that victims should be forced to pay for the reports they file and then don’t pursue.

Moreover, there are so ‘many’ women in Malta’s parliament’s ruling faction that the new prime minister recruited them all into the executive branch, narrowly avoiding an all-male government.

Surely, one might argue that positions of power are so full of men because Malta’s powerful men are Such. Beacons. Of. Competence. Too competent to compete with. But anybody keen on finding out could witness it book after book, interview after interview, profile after profile, and discussion after discussion what untapped talent, knowledge and achievement rests in numerous women, non-binary individuals, and non-domineering men.

In the current societal structure, ascending to positions of power requires pooling and engaging whatever resources accessible, including class, partisan or clannish loyalty. The fact that some individuals from non-dominant categories reach prominent positions is often a testament not to the system’s openness and meritocracy, but to individuals’ skillful use of these resources.

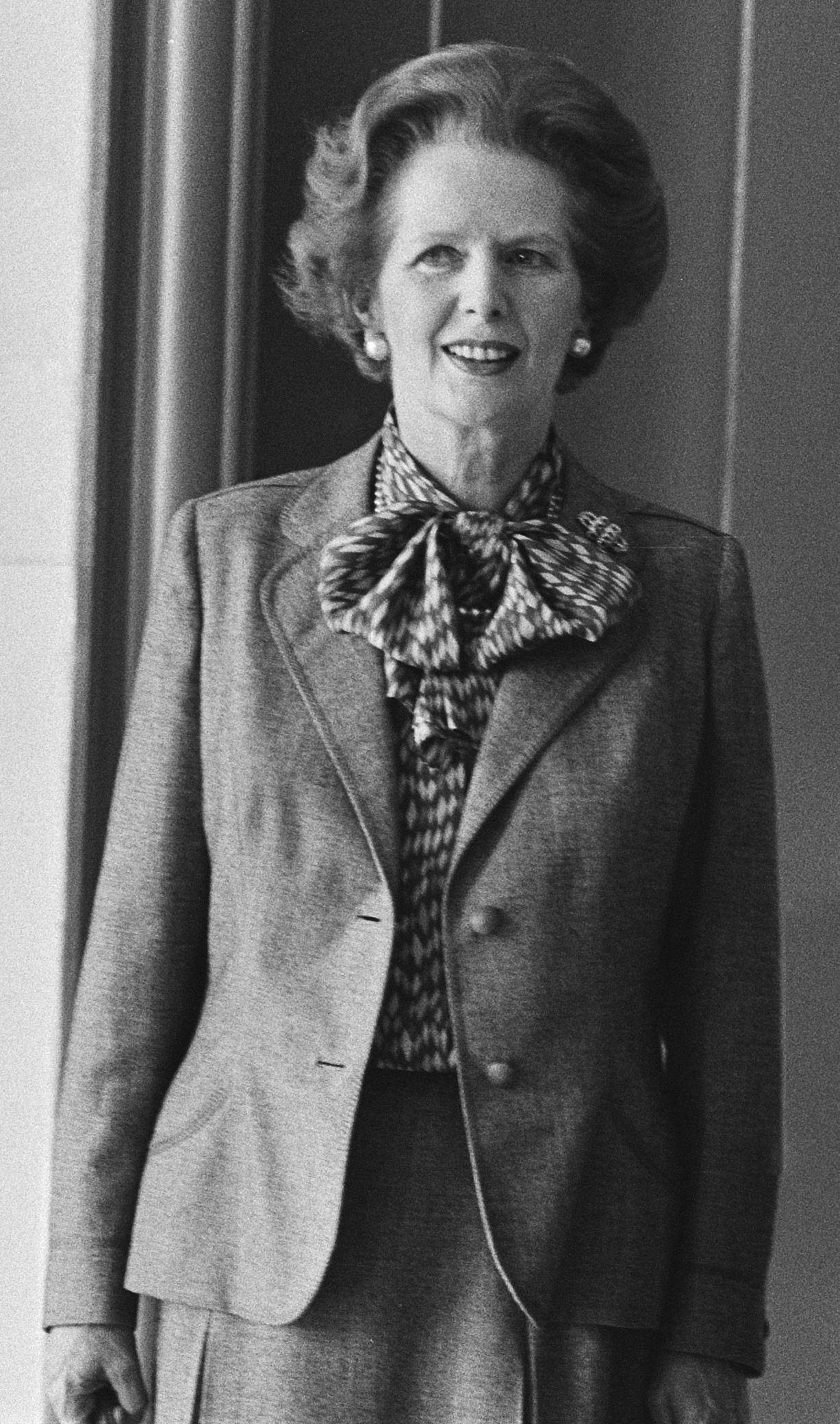

This explains all those examples of women in prominent roles, accepting the terms and conditions prevalent in male-dominated power structures to become instrumental in oppressing subordinate social groups (for example, upper-class women supporting policies that are detrimental to working class women and men—think of the evergreen debate whether Margaret Thatcher was a feminist icon or not). Economic inequality itself curbs a potential for an inclusive feminist movement.

Feminism needs ambition to achieve change, but for the sake of appearing ‘nice’ and non-threatening, activists have to dedicate much effort and emotional labour to soothing their critics’ irrational fears.

No, we won’t hurt anyone.

No, don’t worry, we love men.

We will patiently educate any bigot who cares to engage in a conversation.

We will comfort the destitute, we will volunteer our sparse free time to help everyone in need.

We will suppress our natural anger just to keep conversations going.

We will check our privilege before defending ourselves.

If you are a man who slightly cares about some equality cause, you are always good enough and very welcome, even if you reinforce stereotypes and irrational fears.

All we ask for is a little bit of equality.

Such are the local feminists I know, as I wait to be introduced to my first militant Maltese feminist. But after all the ‘you know’s I’ve heard about feminism, there’s something we should all know: gender equality is a legal principle endorsed today by mainstream democratic governments; but feminism is about more than equality.

At its core, feminism is about justice, which requires reexamination of power structures and redistribution of power. It is about changing the whole society for the better. “Better never means better for everyone”, quoting ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’, and that means privileges will be lost. Influence of men in such a society would decrease, and they may feel deeply resentful as a result. But do men, ultimately, want to be at the top of the suppressed? Is it desirable for anyone to live among hierarchies of oppression?

May the resentment encountered not discourage the budding local movements from seeking justice. Will the real militant feminist please stand up to lead the battle for a better society for all?

Leave a Reply