Why do COVID-19 updates skew so much towards death and not recovery? We need to be particularly cautious in letting numbers of death records beat us into fear. Or do we assume that people will not act responsibly unless they are shocked into a panic?

by Marieke Jochimsen

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]alta has the second worst air quality in Europe. While in 2014 the average of deaths caused by air pollution was 240, this number more than doubled by 2019, when 570 people died of respiratory complications caused by polluted air in Malta. The air is killing us but, unlike COVID-19, this hazard causes no panic among locals.

Going for a bike ride last Thursday, a public holiday during the ‘Times of Corona’, being able to cycle on absolutely deserted streets and breathe fresh air (indeed the air quality index proved to be exceptionally good) invoked ambivalent feelings, mixed with the thought: This is only possible because a pandemic is putting us in an emergency situation.

The Climate of Fear: What Does It Obscure?

Sadly, I doubt that it will have a sustainable effect on acting more responsibly concerning pressing issues of climate change or on global and local injustices after everything has gone back to normal. One reason for this may be that most of us in this situation are, once again, not acting consciously on well-founded decisions, but are rather reacting to a moralizing and dramatizing tone in the media and a construction of an atmosphere of fear.

As the philosopher Richard David Precht said recently about the Corona pandemic: “The fear of the Coronavirus is achieving what the imminent climate collapse hasn’t.” But is this a good thing?

Should we hope that imposing similarly drastic measures in the face of climate change would be possible after this exceptional situation? How far can we go with restricting personal liberty? And what extent could the suspending of democratic principles reach in a truly life-threatening scenario?

Should we hope that imposing similarly drastic measures in the face of climate change would be possible after this exceptional situation? How far can we go with restricting personal liberty?

It is worth observing the change in public opinion about the danger of the virus as it was getting closer, in response to a shift in the media reporting style.

About two months ago, most of us had heard about the Coronavirus, but it still seemed far away and thus something not to worry about. Who, indeed, has heard about the severe dengue epidemic in South America happening at this very moment?

With the virus reaching Europe, however, the topic gained far more coverage by the international and local media (oh, horror! White people are dying!) and the persistence of the topic in the headlines further intensifies our fears. Dramatic tones in updates about the virus, too, became a standard way of reporting.

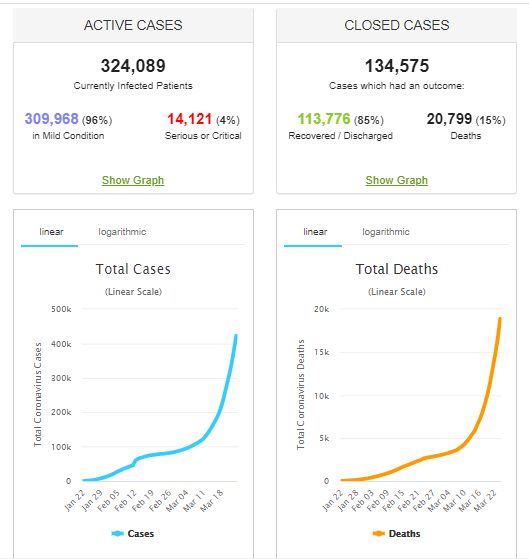

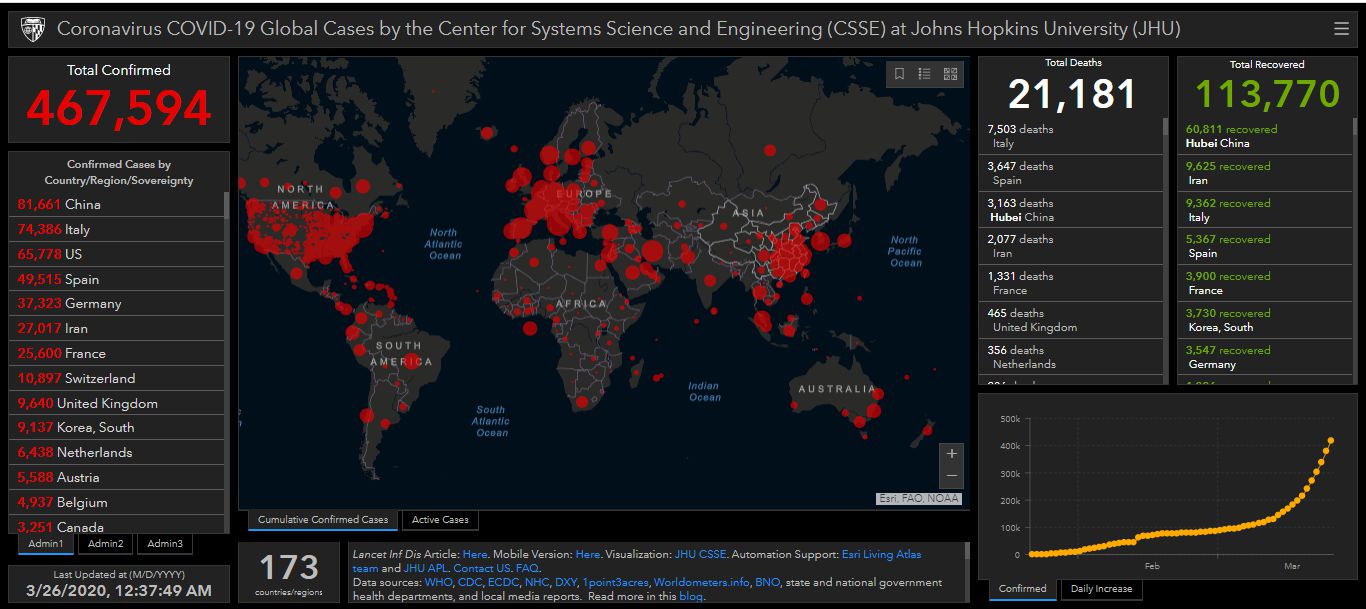

Suddenly, when we started getting daily updates on the number of infected persons worldwide, we began talking about a crisis, of a severe situation, the lives-ticker quickly became a death-ticker, the severe situation—a dark scenario. The virus was no longer a ‘distant threat’; it began killing people, taking its death toll*. Informing the public on the numbers of new cases and deaths—a strategy which otherwise could be labelled as sensationalist and clickbait—left the audience under the assumption that they are being informed in a purely rational way.

On the other hand, accounts of people who had recovered and told their story of what it felt like to have COVID-19 are harder to find.

Meanwhile, the fear of infection had begun affecting our mind before the virus reached our bodies. Supermarkets were running out of toilet paper, while gun sales spiked to alarming numbers in the United States. A psychological scare that went viral much faster than the virus itself has been causing psychological chain reactions, impossible to leave us unaffected on a personal as well as a national level, along the lines of “If he/she/they are doing this, maybe I/we should, too?”

The fear of infection had begun affecting our mind before the virus reached our bodies.

This fear of the unknown was boosted by a feeling of powerlessness in a world where we are used to controlling everything—or at least to being told that everything is under control.

Unfortunately, attitudes deteriorated quickly. First came finger-pointing and accusations (“the dirty Chinese”/ “the chaotic Italians”) in an attempt to ease the tension and to find someone to blame. The second reaction was to stock up with whatever one considered important to regain a feeling of control over the situation: toilet paper, guns, condoms and red wine.

Ministers speaking about “deporting foreigners who lost their jobs” showed that a purported concern for security was, in fact, an excuse to discriminate against foreign workers. Notions of ‘national security’ yet again were fueling xenophobia and racism.

Let Fear Not Be Our Guide

By no means do I intend to say that measures are too drastic or to trivialize the situation.

Even though the coronavirus is very likely to become one of the other viruses of the Corona family we are already living with, the flattening of the curve as recommended by many epidemiologists is now a necessary priority in order not to overburden our health system. This is beyond dispute and people ought to follow the recommendations. However, I do believe that stepping back and looking at the development of the situation helps to assess media strategies of fear-mongering and to re-evaluate the situation more objectively.

One of the questions to ask is: ‘How do the pandemic mortality rates compare to averages?’ An average of around 1700 people a day die in Italy (633,000 people die each year)**. On March 17 alone, 2503 died.

What do the numbers tell us? They say much about dying, but close to nothing about living and surviving. Yes, access to information and trustworthy reporting are indispensable in a democracy, but why does reporting skew so much towards death and not recovery? Or do we really need to assume that people will not act responsibly unless they are shocked into a panic?

Why does reporting skew so much towards death and not recovery? Or do we really need to assume that people will not act responsibly unless they are shocked into a panic?

Shouldn’t the media refrain from reporting about “daily death records” and provide more insight into the methods of calculating the death rates and error margins of such calculations?

How is it, for example, possible that the current fatality rates range from 8% in Italy to 0.3% in Germany? Higher rates of smoking and air pollution in the Lombardy region of Italy as well as the overburdening of the health system by the surge of Covid-19 patients could be part of the reason, with a usual high occupancy of northern Italian hospital’s ICUs of 85-90% in winter months.

There are many other questions we should be asking.

Professor Walter Ricciardi, the scientific advisor of Italy’s Minister of Health, also assumes that Italy’s mortality rate is far higher because of its demographics and the hospitals’ deaths recording method.

“The age of our patients in hospitals is substantially older—the median is 67, while in China it was 46,” Prof Ricciardi says. “So essentially the age distribution of our patients is substantially squeezed to an older age and this is substantial in increasing the lethality.”

Together with other experts, he has also expressed scepticism about the fatality counting, admitting that “only 12 per cent of death certificates have shown a direct causality from coronavirus, while 88 per cent of patients who have died have at least one pre-morbidity—many had two or three,” he says. A fact that makes it hard to distinguish whether they died with or from the disease.

Another factor that shows the problem with mortality rates is the selection bias in testing which can mean that those with severe diseases are preferentially tested leaving an unknown number of cases in the dark. More and more voices are now pointing out that the data that is being collected is thus not very reliable causing a tremendous uncertainty about the risk of dying from COVID-19.

Of course, numbers also have to be put into relation with healthcare systems that are already strained by financial cuts and the general principle of saving economic costs rather than saving lives at all cost.

One problem is that we are fed numbers which project a simple readability when actually, at all times, statistics are hard to interpret and need a lot of context to be meaningful. These examples show that we need to be particularly cautious in letting numbers of death records in newspaper headlines beat us into fear and treating others with suspicion.

Amid all these screams of fear and panic, on 19 March 2020, the UK has refrained from classifying COVID-19 as a high consequence infectious disease (HCID), stating that mortality rates are “low overall”. However, since the country’s administration introduced a lockdown only on March 24, the effect of delaying these measures will not be apparent until mid-April soonest.

The takeaway from all of the above is that we should not easily buy into sensational narratives—neither those painting the most shocking picture, nor others willing to justify a lack of state responsibility with comforting rhetoric.

Counting cases of infection and death turns people into mere numbers.

Why aren’t we informed as regularly about the full spectrum of the patients’ experiences though? Classifying those individuals showing mild to no symptoms and the ones who succumbed to the disease as ‘Currently Infected Patients’ and ‘Total Deaths’ reduces their experiences and humanity to simply being coronavirus hosts and victims. Counting cases of infection and death turns people into mere numbers.

The World Will Go On, but What Will It Be Like?

As the pandemic occupied the front pages, it is easy to forget that life is going on nevertheless. What else is happening in the world that is worth reporting?

The impact of fear of death will most certainly affect our mental health and the mortality rates might become even higher—but as a result of exacerbated mental health issues in this toxic climate of fear and panic. After all, there seems to be a connection between fear and our health, whereby fear and living with a constant threat is said to weaken our immune system, potentially even leading to premature death. In this sense, the quote of the humanist and Nobel Prize winner Naguib Mahfouz takes a new significance: “Fear doesn’t prevent death, it prevents life”.

The impact of fear of death will most certainly affect our mental health and the mortality rates might become even higher—but as a result of exacerbated mental health issues in this toxic climate of fear and panic.

“In this time of crisis, we face two particularly important choices”, says Yuval Noah Harari in his article The world after coronavirus. “The first is between totalitarian surveillance and citizen empowerment. The second is between nationalist isolation and global solidarity.” Do we want to hand over these important decisions to fear?

What will the world, our societies and our lives be like once this saga is over?

Shall we hope that the government will impose similarly drastic measures to address other urgent problems on our agenda? If morbidity and death are of so much interest to us, why don’t we set up a daily counter of domestic violence victims or those dying of respiratory complications due to poor air quality?

Imagine how we could change the behaviour of a whole planet if we were reminded about the air pollution index of our city, and would sit at 12 o’clock in front of our laptop waiting excitedly for the most recent updates on whether it had dropped or increased?

Should we hope that similarly drastic measures are imposed for the long overdue paradigm shift to ecological and economic sustainability and degrowth?

Should we hope that similarly drastic measures are imposed for the long overdue paradigm shift to ecological and economic sustainability and degrowth in order not to exploit and destroy those on the losing side of the capitalist game—nature and most of the not so wealthy parts of the world? Or should we hope that this crisis will raise awareness of opinion-forming strategies in the media enabling us to be more autonomous, self-reliant and critical citizens of a democracy?

* Words in italics collected from various national and international news pages.

** a number stated by Tim Pranks in his entry in Pandemic Journal by the New York Review of Books.

Leave a Reply