As British colonial rule successfully employed various tactics to legitimize its control over the Maltese fortifications, so the needs of the civilian Maltese inhabitants living within these fortifications were progressively subordinated to those of the island fortress.

by David Edward Zammit

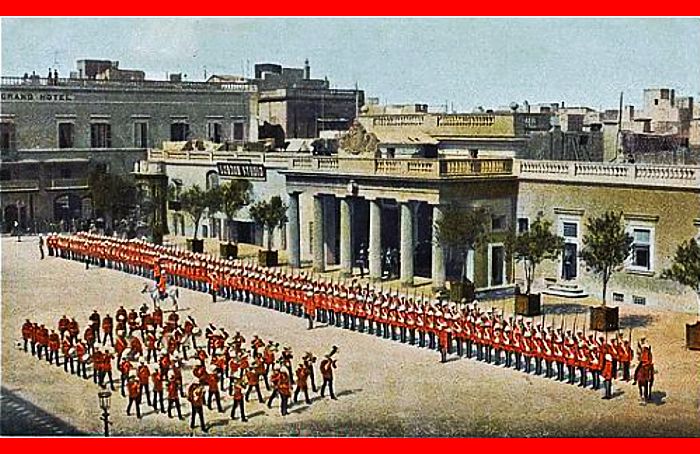

Image: Palace – Square with Main Guard parading, Valletta, Malta Date: 1911

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n my previous article on Carnival in the early British period, I argued that British colonial rule was premised upon a ‘strategy of continuity’ with the Knights, which had various political uses and has left an impact even on contemporary Maltese society.

This essay explores how military ritual served both to symbolically assert British military continuity with the Knights and also to put the ‘native civilian population’ in their place, culminating in the effective eviction of native Maltese from property which had belonged to the Knights.

Here, I focus on three areas of ritual/symbolic activity through which the legitimacy of exclusive British control of Knight-period spaces was affirmed: using bastions as burial sites for British high-profile officials, appropriating squares for military parades and public executions.

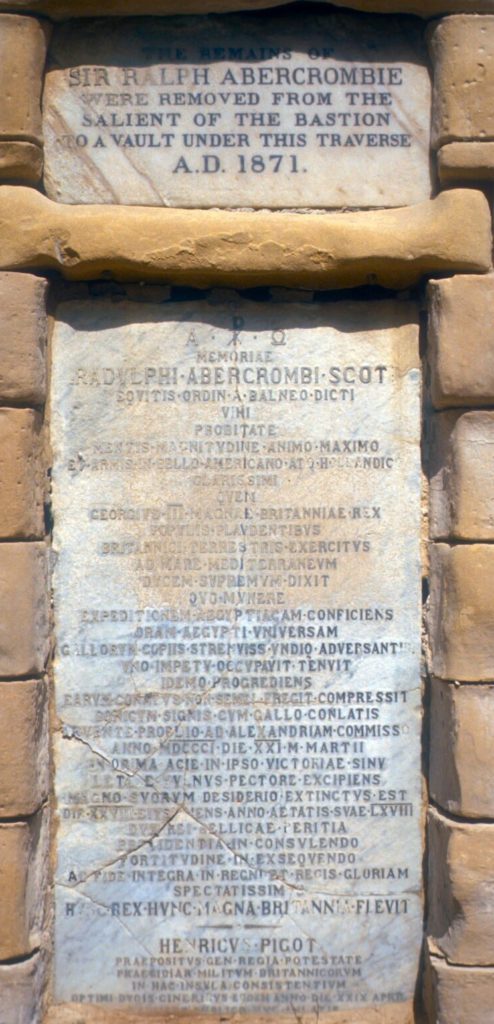

Bastions as Burial Sites

‘If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England.’

Rupert Brooke, The Soldier, 1914

Over the course of the first decade of the nineteenth century, Sir Alexander Ball and Sir Ralph Abercrombie were both buried in the bastions of Fort Saint Elmo. As a mid-century travel account describes it:

On the angles of the ramparts are two turrets, formerly used as places of look out: at present, however, they are closed with two slabs, one bearing an inscription to Sir A. Ball, formerly governor of Malta; and the other, a similar one, in memory of Sir Ralph Abercrombie, whose embalmed body is enclosed in a barrel within the turret, just as it was brought from the battle of Aboukir: hence, the bastions to the west are known by the name of Ball’s, and those to the east by the name of Abercrombie’s bastions.

A few years later, these high-ranking British officials were to be joined by another two Governors: Sir Thomas Maitland and the Marquess of Hastings; each buried in commanding positions of importance in the bastions around Valletta.

Beautiful ‘Greek Temples’ in the Lower Barakka and Hastings gardens commemorate the memories of Ball and Hastings. An obelisk marked the bastion where Capt. Hon. Sir Robert Spencer was buried and former Governor Sir Frederick Cavendish’s burial site in Saint Andrew’s bastion, Valletta, was marked by a seventy-foot tall marble Doric column.

Meanwhile the ‘Protestant Burial Ground’ was also established in the Floriana bastions facing Pieta in this period and served for lower-ranking Protestant British officials and personnel who could not be buried inside Catholic churches with the Maltese natives. Bastion burial was so prevalent that: ‘Since the English became masters, the proud bastions of Valletta have become sepulchral’.

Apart from the obvious message about British succession to the Knights’ military role transmitted by the fact of bastion burial itself and the strong association established by neo-Classical funerary monuments between Crusading Knights and the new British defenders of Western civilization, these burial practices also established a clear spatial demarcation between the British dead and the native Maltese.

A contemporary magazine* observed: ‘The English burial-ground is a pretty spot, planted like an English flower-garden; but those belonging to the natives are mere depositories of the dead, and, very properly, further removed from the city.’

Thus bastion burial created a spatial hierarchy of burial places; with British officers moving into and appropriating the Knight’s fortifications in and around Valletta while ‘native’ dead were ‘further removed from the city’.

Thus bastion burial created a spatial hierarchy of burial places; with British officers moving into and appropriating the Knight’s fortifications in and around Valletta while ‘native’ dead were ‘further removed from the city’. The strategy of (British) continuity with the Knights and the concomitant exclusion, subordination and marginalization of the ‘native Maltese’ could hardly have been given a clearer architectural expression.

Tournaments in Palace Square

Under British rule, the symbolic military potential of the large square in Valletta adjoining the Governor’s palace was recognized and exploited to the full. This square was used for military parades, the building opposite the Palace was renamed the Main Guard and a marble slab was fixed to its façade by Governor Maitland asserting (in Latin) that the Voice of Europe and the Love of the Maltese had consigned Malta to ‘Great and Unconquered Britain’.

The heavy militarization of this square as a spectacular space is clearly suggested by a contemporary anecdote which states that: ‘One day he (Governor Maitland) was working in his shirt-sleeves in the Throne Room of the Palace; the troops meanwhile were parading on the square. The stentorian orders, however, the beating of the drum and the tramp of the men’s feet, were too much for King Tom. He rose from his desk, rushed to the balcony and in as loud a voice as he could command: “Form threes” he shouted, “right turn and go to hell.” **

In the first decades of colonial rule, Palace Square was put to use in an even more ambitious ceremonial activity, which was nothing less than the recreation of a medieval tournament in Victorian Malta.

In the first decades of colonial rule, Palace Square was put to use in an even more ambitious ceremonial activity, which was nothing less than the recreation of a medieval tournament in Victorian Malta. One of the main motives appears to have been to utilize the armaments left behind by the Knights to enact feudal hierarchy as a way of expressing continuity with them and aloofness from the ‘native’ Maltese who could not take part in these tournaments***:

There was a great tournament held by the officers of the garrison, in the panoply of the Knights of St. John. The lists were enclosed in the Palace square, and the warriors made a splendid appearance in the previous pageant, in which they paraded round and round under their several leaders, with their squires and pages; but when they came to the charge, it was a sad slow concern.

One horse misunderstanding the nature of the military order of monk which he carried, went down upon his knees in a most ecclesiastical way; another went on his nose; one stood on his tail; and another fairly took fright, and galloped with his rider all round the lists, the rider having got his cloak blown over his eyes, and thus being unable to see to extricate himself.

At this final catastrophe, half of the gallant knights followed the fugitive, basting him over the back with the end of their lances, turning the fight into a sort of equestrian blindman’s buff, or hunt the hare.

The humour in this account plays on the anachronistic nature of the whole re-enactment. Not only did the horses—not having been trained in the art of medieval horsemanship—conduct themselves erratically, but the attitudes of the officers themselves left much to be desired.

They were far from gallant and courtly knights, however much they might dress themselves up ‘in the panoply of the Knights of Saint John’. Yet the strategic intention behind the anachronism is unmistakable: British officers revealing to amazed natives that they were the true successors of the Knights; the attempt to deny the passage of time and the advent of the industrial age and to re-establish via military technology, racialized feudal hierarchies of authority and obedience between submissive natives and commanding Knights.

The strategic intention behind the anachronism is unmistakable: British officers revealing to amazed natives that they were the true successors of the Knights.

In this strategy, Palace Square was operationalized as a kind of architectural ‘chronotope’; a time-space device by which a continuous military feudalism could be evoked and reproduced. In this continuum Knights and Natives exist in an enchanted cyclical time of their own; which does not intersect with the time of post-Enlightenment European societies.

Gibbets on Gallows Point

On the 26th January 1820, the Malta Admiralty Court met to pass verdict on a group of convicted English pirates led by an American, Christopher Delano; after what appears to have been the first jury trial to be held on the island.

The Court was presided over by the Governor: (General) Sir Thomas Maitland, assisted by Sir Waller Wrodwell Wright, the President of Her Majesty’s Court of Appeal in Malta and a distinguished freemason, the Hon. Anthony Maitland, temporary Commander ‘of His Majesty’s Naval forces in the Mediterranean’ and the Governor’s nephew and another three Commissioners. The verdict they issued—subsequently printed and published as part of the trial record in a pamphlet(*)—is remarkable for its solemn language and for the spectacular manner in which the death sentence on the eight ringleaders was to be inflicted.

The Williams brig ‘being the vessel in which the unfortunate convicts committed the flagrant and most atrocious act of Piracy’(*) was to be ‘painted black, hauled out and anchored in the middle of the Great Port of Malta, viz : —that of Valletta’.(*) The eight pirates were to be hung upon it until they were dead; so that their final struggles would be witnessed by the population of Valletta and the Three Cities.

The eight pirates were to be hung upon it until they were dead; so that their final struggles would be witnessed by the population of Valletta and the Three Cities.

Subsequently, the bodies of the executed were to be: ‘cut down, put in open shells and protected by a proper guard from His Majesty’s ships (to) be carried to the appointed place, viz: — Fort Ricasoli, where, the body of the late Charles Christopher Delano, late Captain of the William, is to be hung in irons on the right hand Gibbet, next to the Port of Valletta, erected for this purpose in the north west angle of the said Fort.’

The verdict continues to give detailed instructions as to how the other pirate corpses were to be disposed of. Three of them were also to be gibbeted on different angles of the bastions of Fort Ricasoli; whereas the other four were to be interred at their feet. The four gibbeted corpses were visible from Valletta with a spyglass and subsequently labelled ‘King Tom’s Whist Party’ by British servicemen.

The following anecdote, taken from the mid-19th century novel ‘The Pirate of the Mediterranean’ shows how these gibbeted corpses were later remembered as victims of ‘King’ Thomas Maitland’s autocratic style of governance:

“Take that glass and look at the outer bastion of Fort Ricasoli. What do you see there?”

“Four figures, which are hanging by their necks from gibbets,” answered Dufi”.

“What are they?”

“Those are four Englishmen, (at least, one, by the way, was a Yankee, their master) who turned pirates, and tried to scuttle another English brig, and to drown the people. It’s too long a story to tell you now. But old King Tom got hold of them and treated them as you see.”

The four gibbets were to remain in position on the Ricasoli bastion for at least seven years more; sending a powerful and disturbing message regarding British sovereignty to natives and sea-going visitors alike.

As the American visitor Andrew Bigelow observed:

There is another set of objects which can only be looked upon with unmixed horror, which one is compelled to see as his eye glances along the coast below Fort Ricasoli. It is the spectacle of four pirates hung in chains, who were executed several years ago, and have remained on their gibbets ever since. They are kept there ‘in terrorem,’ — as scarecrows; for the crew of every vessel is forced to see them on entering the harbour.”

The macabre medieval practice of hanging corpses in gibbets outside the castle walls was thus revived in nineteenth century Malta via a strategy which was as intentionally archaizing as holding tournaments in Palace Square.

The practice of gibbeting was to be abolished in England only seven years after Bigelow’s visit and Bigelow himself questioned: “why inflict on all peaceable and honest people the inevitable sight of what must be so shocking? Nothing can be more hideous, especially when the wind is high, than to behold even from a distance those carcasses, in their tattered coverings, dangling to the breeze.”

Part of the answer to Bigelow’s question is that the location and method of execution had been carefully calibrated to convey a message of continuity with and succession to the Knights.

The location and method of execution had been carefully calibrated to convey a message of continuity with and succession to the Knights.

In fact the site where the gibbets were located under Fort Ricasoli had been known as Gallows Point or Punta delle Forche ever since the first Grandmaster, Villiers de l’Isle Adam, had erected a stone gallows there. The Ricasoli gibbets thus brought together various aspects of the British policy of freezing time; including:

- the strategic re-enactment of archaic practices,

- succession in sovereignty to the Knights,

- exclusive control over the fortifications and

- hierarchy of command based on the fear and respect of the natives.

It seems that Wrodwell Wright even tried to go a step further than the Knights in giving the process of execution a local flavour : ‘Red was formerly the favourite colour for caps; but Judge Wright having ordered that the hangman, who had previously operated in a Sicilian dress, and black hat, should thenceforth appear in a Maltese costume, with a red cap, the colour lost favour among the better classes of the peasantry.’

As British colonial rule successfully employed military spectacles to legitimize its control over the Maltese fortifications, so the needs of the civilian Maltese inhabitants living within these fortifications were progressively subordinated to those of the island fortress.

Two incidents, one occurring near the beginning and the other towards the end of colonial rule, shed light on this process.

On the 18th July 1806, the gunpowder magazine located beneath the Birgu fortifications caught fire causing: ‘a massive explosion which annihilated the working party, 3 soldiers of the 39th Foot, and 23 soldiers of the Maltese Infantry. Two hundred men, women, and children were also killed; another 100 were injured by falling masonry.’

Upon being told of the request for compensation made by some of the surviving civilians, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Lord Castlereagh dismissed their claims: ‘curtly stating that those who inhabit a fortress must be subject to the risks connected with it, whilst they participate in the advantages the situation commands, and it is their duty to secure themselves from casual accidents by insurance.’

“Those who inhabit a fortress must be subject to the risks connected with it.”

A similar inversion in the respective importance attributed to the military and civilian spaces and persons emerges from a personal reminiscence by Judge Giovanni Bonello, recently published in the ‘To be Defined’ art-book documenting the eponymous exhibition.

He recounts how as a small boy in 1945/46 he swam across the harbour from Valletta to Manoel Island with some other boys; only to be met by a sentry on the island who insisted that the children had to leave immediately: ‘I tried to reason with him; I told him I was very tired, and that I might not have the strength to make it back. He replied: ‘that’s your problem, not mine. Leave right away or I’d have to arrest you.’’

![]()

David Zammit is Head of Department of Civil Law at the University of Malta. His interests include Anthropology of Law, Tort Law, Law and Narrative, Administration of Justice, Anthropology of the Mediterranean.

Leave a Reply