Maltese working women, married or otherwise, is not a recent phenomenon. Historical sources prove the claim that three centuries ago, in 18th century Malta, women’s input into the work of production was indeed significant.

by Yosanne Vella

Artwork: Ruins of Phoenician Temple in Casal Caccia by Jean Pierre Laurent Houël, late 1770s.

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]istorians do not work in a vacuum; consciously or subconsciously they tend to follow some school of thought on history while working on their research. I distinctly remember some 15 years ago, at the end of a presentation I gave on 18th century women in Malta, one member of the audience, a female German historian, quite furiously accused me of giving a male interpretation of history and not a feminist one. A very interesting discussion followed which has since made me think how I, as a historian, had approached my sources, and indeed, on reflection, parts of my research can be described as falling under certain methods of historiography I had employed without fully realising it.

In my opinion, a particular aspect of my research, which focused on the types of work women performed in 18th century, could be attributed, if only loosely, to the Marxist paradigm. Now, unlike Christopher Hill, who always made it clear in his work on 17th century England that he is a Marxist historian, or Mark Camilleri, who sets the record straight by the very title of his book A Materialistic revision of Maltese History 1919-1979, Marxist elements in my analysis are of the subtle type but they are possibly Marxist history writing just the same.

Karl Marx’s central thesis about history was that it is shaped by material conditions. The Marxist paradigm is that history is all about the development of human productive power which in turn influences social life. The first historical act is thus the production of the means for satisfying human needs, the production of material human life itself. Thus, my research considered women as groups of workers who formed part of this essential form of human activity, that is, productivity.

In my research I chose to view women as active participants in history. Since history, according to a Marxist interpretation, is subject to economic forces, my aim was to establish the extent to which Maltese women shaped the economy of the time.

Instead of sharing stories of individual women in 18th century Malta, I focused on female labourers, particularly in agriculture, and shop owners—two among a few other groups which earned a living outside the domestic sphere. This does not mean that the unpaid reproductive work in the household, which was the main realm of female work in the 18th century (and still largely is today), has no economic significance, but my focus here is on women in the—traditionally male—field of production, which is also the predominant focus of most Marxist approaches.

Women in Agriculture

One of the main strengths of Malta’s economy in the 18th century was agriculture. This was one area where women were employed.

As would be expected, they worked on family farms as daughters and wives. However, besides this type of work, they also engaged in paid labour in agriculture—a little known fact in Maltese history. Paid work in agriculture for either men or women was not a typical arrangement for 18th century Malta; however, I found an 18th century register* which proves that women were in fact doing this type of work. This register shows a list of labourers employed at Marsa to work on fields owned by the state—that is by the Order—in the period of August 31st 1771 to May 7th 1774, and it contains information on the weekly wages being paid to the employees.

About a quarter of the labourers were female, grouped together at the bottom under the heading “Women”. From their surnames one can only conclude that a number of the male workers must have been related to the female ones, and in all probability were their husbands. So here we, most probably, have an example of 18th century married working women! Unfortunately, the work they did is not specified. There is nothing to show that they were engaged in skilled work, similar to that done by women in Tuscany; there the Ospedale degli Innocenti had a system where the farmer’s wife taught girls a range of skills. In the Marsa fields women might merely have been carrying buckets; farm work typically identified as women’s work in many parts of Europe.

Without exception, women’s wages were lower than those of men. To cite just one example, a close analysis of the items in the register’s balance of the 17th July 1773 gives the indication of the differences in pay. At that point in time, there were 50 male employees and 18 female employees. The most common working week varied in length from six days to six and a half days. 70% of the men who worked at the Marsa fields were paid rates varying between 3 and 3.5 scudi per week, whilst the women were paid rates which varied from 2 scudi to 2 scudi 2 tari.

Shop owners

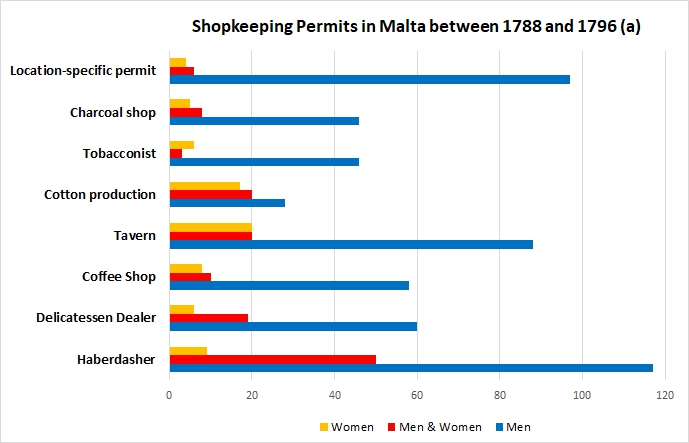

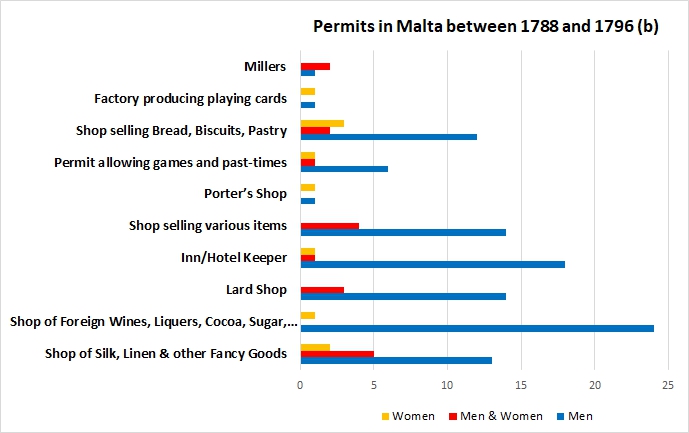

Women were also frequently shop owners. In my research I mention a number of women throughout the 18th century who were managing all kinds of shops, but, apart from these individual cases, further evidence of female shop owners can be traced in a register of licences** which has survived.

This register was issued by the authorities for the keeping of shops in the period between 1788 and 1796. It is subdivided into sections by alphabetical order following the custom of the time, that is, according to the Christian name of the applicant rather than the surname. When collecting data, I ensured to eliminate cases of duplication, which arose from the grant of a licence to two or more persons registered in different places in the book. Licences were granted, sometimes to men only, sometimes to women only and sometimes to women and men operating jointly in business. Excluding the duplicates, this register contains a total of 829 permits.

Of the 829 permits women were directly involved in 199 (24%) of the cases. This is more than a clear indication that, contrary to the common belief that women maintained a passive role in Maltese society, outside of the private household, even in the 18th century they were active in commerce and retailing.

Women as Economic Force in 18th Century Malta

From just these two spheres of work, agriculture and shop keeping, it is clear that Maltese women did engage in paid employment in a pattern which was not dissimilar to women’s work in other parts of Europe. One very important difference worth noting between Malta and many European countries was the absence of any sort of formal craft guilds. This might have created a more flexible playing field compared to other parts of Europe, for there does not seem to have been any regulations or restrictions which limited or excluded women from certain work.

The silk confraternities of late sixteenth-century Lyons, for example “allowed only two apprentices per master and specified that, if they were females, they had to be daughters or sisters of members”, while the London Stationers Company in the 17th century started to accept only male apprentices, thus putting a stop to all females who had previously been printing, binding and selling books. Between 1553 and 1640, 10 percent of publishers in the London company had been women.

Therefore, Maltese working women, married or otherwise, have been around for quite some time. Apart from agriculture and shopkeeping, in the 18th century they were employed in a variety of occupations, such as cotton spinners, dressmakers, washerwomen, bakers and theatre actresses. Historical sources cited above prove the claim that, in 18th century Malta, women’s input into the work of production was indeed significant.

* Palace Archives, Ms. Misc. 60: Spesa Della Marsa

**Palace Archives, Ms. Misc. 60: Libro in cui s’annotano le rebilitazioni de mercanti, negoziantie bottegar

For further reading on women and work in 18th century Malta see Women in 18th Century Malta by Yosanne Vella.

![]()

Yosanne Vella is an Associate Professor at the University of Malta and the History and Social Studies co-ordinator of the Faculty of Education. Her areas of research mainly focus on finding effective history pedagogy that involves children’s history thinking and understanding.

Leave a Reply