From peace activists and workers to consumers of pink glittering glamour: postcards narrate the change of women’s roles in Russia for the past 65 years.

by Raisa Galea

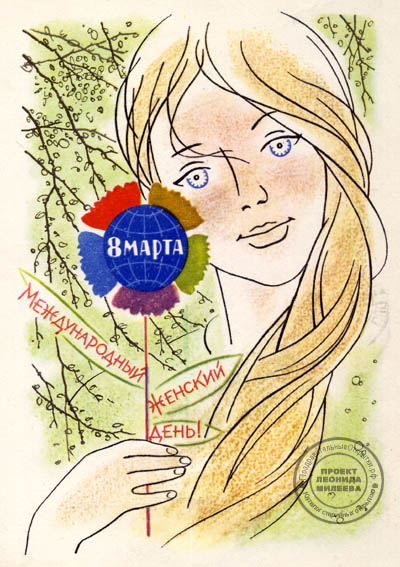

Image: postcard from the early 1960s

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]nternational Women’s Day has always been a special date to me ever since early childhood. In Russia, where I was born and grew up, 8th March was and still remains one of the most popular and broadly celebrated public holidays of the year.

This date tells the story of international suffrage. The first proposal to introduce a Women’s Day was voiced on February 28, 1909 in New York. The first celebration of International Women’s Day happened on March 19, 1911 in Berlin.

It is essential to remember that this initiative was put forward by working women who did not feel at home with mainstream feminism of the day. “Bourgeois feminism and the movement of proletarian women are two fundamentally different social movements”, Clara Zetkin wrote in the Social Democratic women’s magazine Die Gleichheit (Equality) in 1894. This celebration, therefore, was one of the achievements of the women of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) whose organisational strength inspired the International Socialist Women Movement.

International Women’s Day in Russia

Women’s Day in my native country too has a long history.

In the Russian Empire, its first celebration in 1913 was rather a tribute to the emerging Western trend. On March 8, 1917 (23rd February by the Julian calendar then used in Russia), thousands of female textile workers took to the streets of Petrograd (St. Petersburg) demanding ‘Bread and Peace’. The event was the catalyst of the February Revolution which paved way to the October socialist revolution of the same year. In 1921 International Woman’s Day was established in socialist Russia to commemorate this strike; it became a special day in the county torn apart by the civil war. However, only half a century later did Women’s Day receive the final state recognition in the USSR: in 1966 it eventually became a public holiday. It took even longer before the date was adopted by the United Nations in 1975.

Gradually, International Woman’s Day in the USSR was losing the political and feminist meaning behind it, until it became a day for all women.

My memories of the celebration date back to the early 1990s, which were the years of my childhood. Women’s day was populated with requisite school concerts and crafting of presents for female relatives. There were flowers, poems and greeting cards from male classmates. Women’s Day was also dubbed a Day of Spring and Beauty and that finally cemented its ideologically sanitised substance. The image of this public holiday in contemporary Russia is exclusively private and stands somewhere between Valentine’s and Mother’s day.

The image of this public holiday in contemporary Russia is exclusively private and stands somewhere between Valentine’s and Mother’s day.

I began to comprehend the symbolic significance of this date in 2010, when I ‘celebrated’ it away from Russia for the first time. None of my Maltese colleagues were aware of such a thing as International Women’s Day and, for the first time in few months, I felt homesick.

Despite its ideological hollowness, March 8 was the day I used to look forward to and the absence of any celebration was deeply alienating. The following years in Malta helped me to admit how much for granted I took the seeming gender equality of my previous surrounding. It was Malta where I rediscovered the feminist and the revolutionary connotations of the Women’s Day. I cannot but note with enthusiasm the progress this date has made here for the past decade: in 2018, a series of events were organised by the activists to raise awareness of the persisting gender inequality, culminating in ‘Raise Your Voice!’ march in Valletta.

Postcards Narrate the Change of Women’s Roles

The meaning of International Women’s Day in my life underwent a radical change. No longer do I regard it as an occasion to receive gifts and greeting cards. However, I do miss the particular ingredient of the Russian March 8—the cards themselves. As an avid collector of post- and greeting cards, I treat these pieces of carton with awe.

Postcards can be remarkable narrators of history. Mass celebrations of state holidays were an indispensable part of the Soviet lifestyle, thus there were also greeting cards designated for such occasions. These cards introduced a personal dimension to the state holidays—May Day, Victory Day, Revolution Day and Women’s Day. Exchanging cards meant that both sender and receiver engaged into public celebrations privately, by sealing them with intimate relationships. These cards were ideological canvasses upon which the greetings, messages of friendship and personal stories were written; they merged public with personal. This way, the state ideology entered private lives.

These cards were ideological canvasses upon which the greetings, messages of friendship and personal stories were written; they merged public with personal.

Although the greeting cards dedicated to the majority of public holidays became obsolete soon after the fall of the USSR, International Woman’s Day cards were an exception: they still are available in Russia in a great variety of designs. The continuous representation of March 8 in greeting cards allows us to take on a journey through history, to witness the gradual changes that occurred to the perceived social roles of women during the decades of Soviet rule and in the contemporary Russian society.

![]()

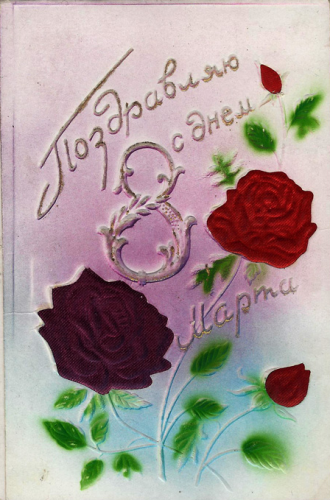

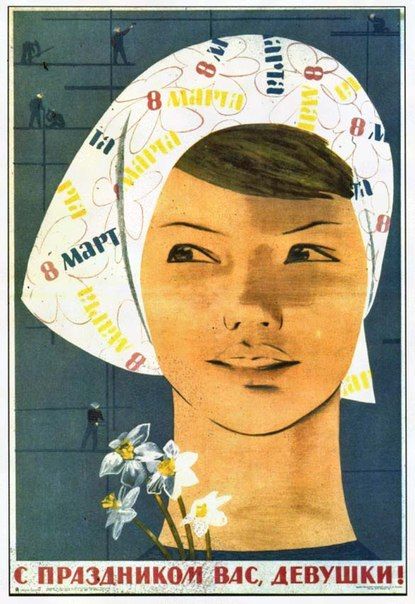

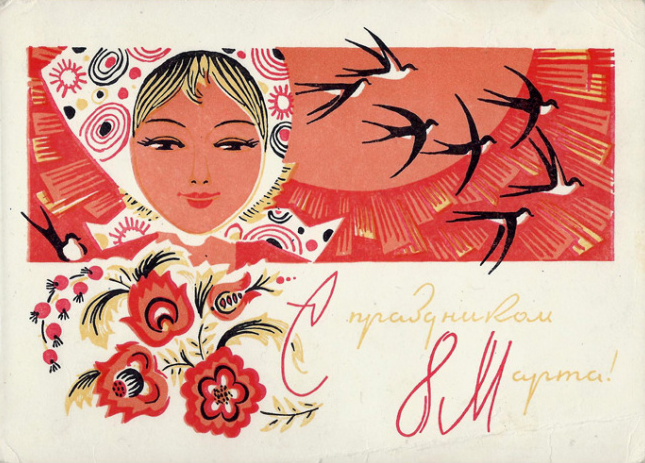

The first cards commemorating International Women’s Day were released in the 1950s. The cards of this period feature a variety of themes—from abstract flowery designs, to paying homage to women as workers and active members of society. Some designs emphasised women’s traditional roles as mothers.

![]()

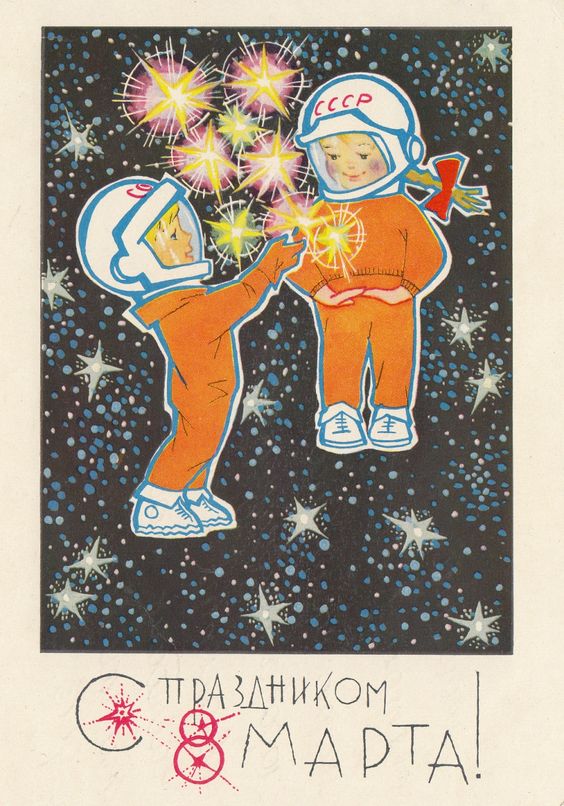

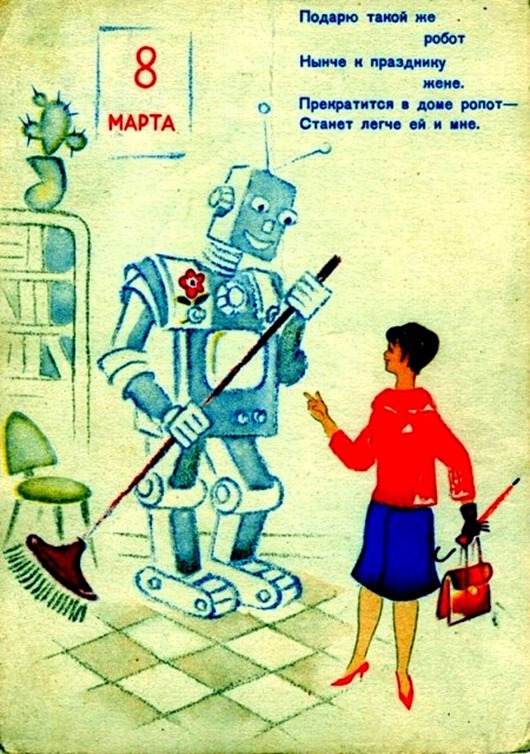

The postcards of 1960s depicted the international nature of the celebration. The female protagonists on these cards are workers and, traditionally, mothers. Another popular theme—a space explorer—adds to the list of the roles.

![]()

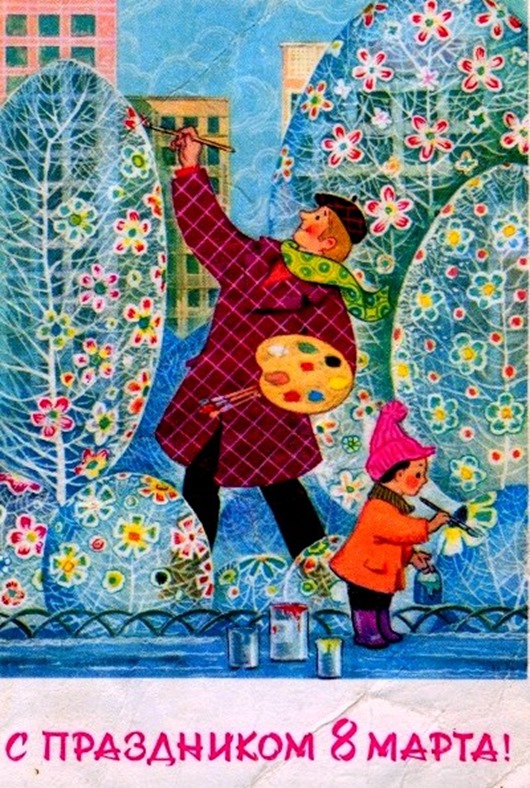

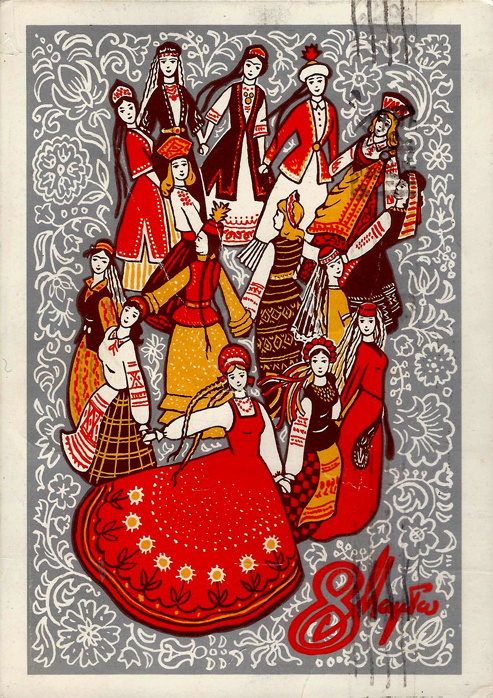

The designs of 1970s and 1980s were more abstract. Often, cards depicted the arrival of spring, with melting snow, tulips and mimosas. Another popular theme was the global significance of the date and its dedication to global peace. Such abstract artworks of Soviet International Woman’s Day greeting cards made them a universal gift to women of all age and occupation.

![]()

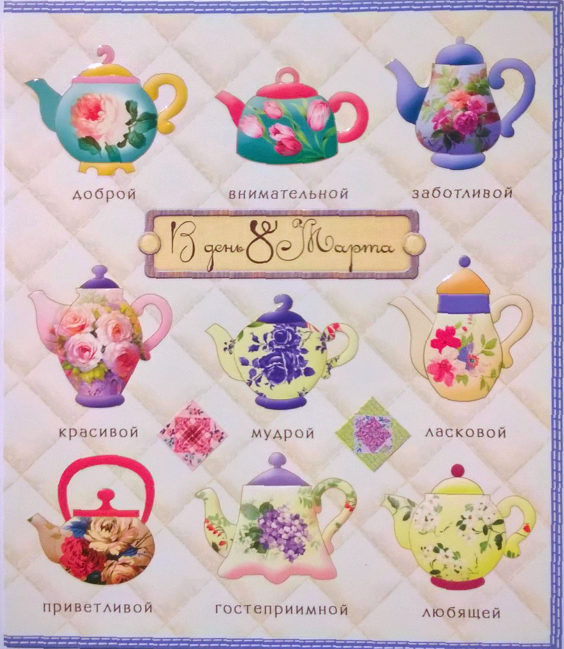

Contemporary Russian cards appeal to women privately. In their pink glittering glamour, they stereotype womens’ role as consumers, preoccupied with prestige of their lifestyle and appearance. The cards of the current decade feature bags, mirrors or clothes. Some designs reproduce kitchen garments, thus implying a domestic role of women. Abstract flowery designs still remain popular.

The transformation that International Women’s Day underwent in public perception is truly striking. The cards of 1950s and 2010s are worlds apart. The sequence of designs narrates the emancipatory process in reverse: from a veteran, peace activist, worker, an active member of society, the socially accepted domain of women in contemporary Russia has shifted to that of glamour and gender-defined consumption.

Leave a Reply