Whenever violence against women is discussed, someone inevitably asks, “but what about men?” This ‘whataboutery’ is usually directed solely towards those who speak out on typically women’s issues and ironically proves the importance of focusing on this particular form of violence.

By Liza Caruana-Finkel

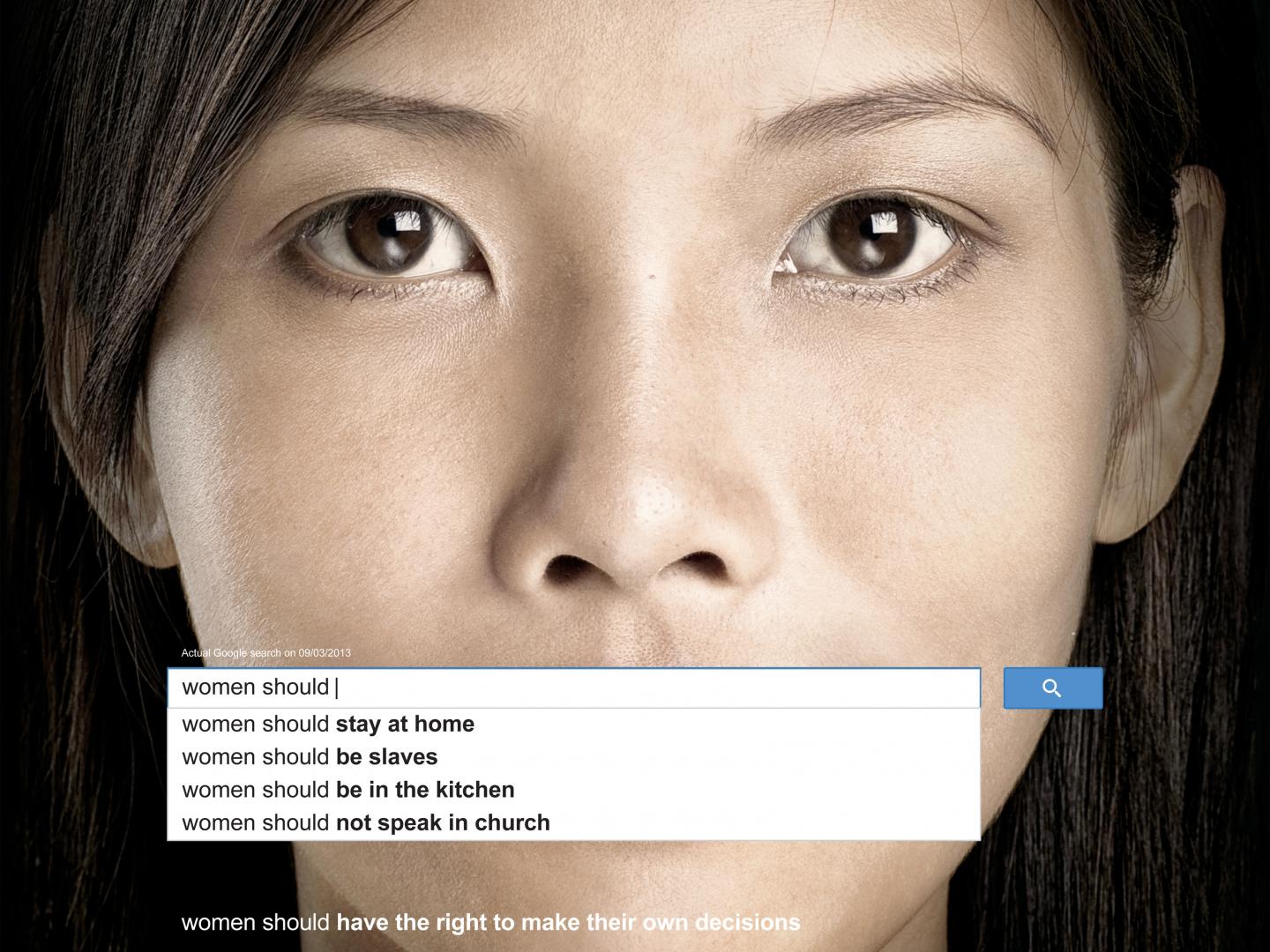

Image by Isaac Claramunt for UN Women

“If women were human, would we have so little voice in public deliberations and in governments in the countries where we live? […] Would we be beaten nearly to death, and to death, by men with whom we are close? […] Would we be raped in genocide […] and raped again in that undeclared war that goes on every day in every country in the world in what is called peacetime? […] And, if we were human, when these things happened, would virtually nothing be done about it?”

Catherine MacKinnon in ‘Are Women Human?’

[dropcap]V[/dropcap]iolence against women (VAW) is an act of gender-based violence; a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination against women, specifically because they are women. According to the Council of Europe, it includes physical, sexual, psychological, and economic acts of harm and abuse, as well as threats of violent acts, coercion or deprivation of liberty.

Although violence in extraordinary contexts (e.g. war) is usually highlighted and reproached, violence in the ‘everyday context’ (e.g. domestic violence) is still largely ignored. Yet worldwide, 1 in 3 women will experience physical and/or sexual violence in their lives, most likely from an intimate partner. In England and Wales, 2 women a week are killed by a current or former male partner.

In Malta, with a fraction of the population, more than 15 women were killed in the last 10 years by men close to them—partners, ex-partners, brothers, sons, and nephews. How many more women need to die at the hands of violent men for VAW to be taken seriously? Are women not human yet?

A Specific, Universal Phenomenon

VAW is a hate crime, rooted in power and control, and needs to be considered as the specific form of violence that it is. Social issues are not equally spread, so it is perfectly acceptable and necessary to focus on issues that affect a subset of a population in a very specific way.

It is not sexist to say that domestic violence perpetrators are usually men, because they are. Yet whenever VAW is discussed, someone inevitably asks, “but what about men?” This ‘whataboutery’ is not about equality, but actually comes from a place of misogyny. As the blog ‘Stop asking me ‘what about men?’’ perfectly explains, ‘whataboutery’ is usually directed solely towards those who speak out on typically women’s issues; the same response is not observed with regards to issues affecting men. In this way, the question itself is linked to the causes of VAW, and ironically proves the importance of focusing on this particular form of violence.

Apart from being specific, VAW is also a universal phenomenon. There is no state, no country, no region in this world where women live free from violence.

Apart from being specific, VAW is also a universal phenomenon. There is no state, no country, no region in this world where women live free from violence. It is not confined to geographical locations, distinct cultures, or specific groups of women. Indeed, it is not, and has never been confined to underprivileged or poor women, nor is it perpetrated solely by poor men.

VAW cannot be blamed on socioeconomic factors, such as unemployment. As feminist groups have known for some time, and as well-publicised media has shown in recent years, rich, famous, and powerful men are as likely to be violent as poorer men. The poor are often scapegoats, whereas violence from the powerful to the disadvantaged is often hidden and denied.

The fact that victims/survivors of domestic violence (as well as other forms of VAW) can be middle-class, educated, and employed also shows that focusing exclusively on economic inequality does not address the root cause of the violence. Unsettling these old, established notions may at times be challenging, but VAW traverses multiple boundaries and permeates into all aspects of society.

Although universal, VAW is also particular in the way it interacts with other forms of inequality and discrimination. Multiple forms of discrimination lead to an increased risk for violence. Factors that affect increased discrimination include race, ethnicity, class, migrant or refugee status, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity and expression, religion, and marital status. Violence can also lead to more violence, because not only do multiple forms of inequalities intersect, but so do multiple forms of violence. They are all linked and interdependent.

The Violence of Patriarchy

There is no single cause to be identified in individual perpetrators that can properly and satisfactorily explain or account for the violence committed against women. VAW cannot be seen as dependent solely on an individual’s psychology; it is not reducible to genetics or emotion, nor is it ‘simply’ a random act of misconduct.

VAW is a structural problem that is entrenched in the deep inequality between men and women. It is rooted in the centuries of systemic domination of women by men. In patriarchy. In gender subordination. Inequality is the foundation upon which everything else is built, feeding into male entitlement and toxic masculinity.

Male chauvinism is still prevalent in many cultures, including the Maltese culture. We need to move away from the idea that men need to show their masculinity through machismo; by exerting their masculinity through violence. Dismantling the idea of the patriarchy benefits all of society, not ‘only’ women.

Patriarchy harms men by teaching them to suppress their emotions. They are told early on to ‘man up’ and that ‘boys don’t cry.’ Society makes clear that caring for their own children is not a ‘man’s job,’ but that a father’s role is to provide financially for his family, as though that is all a man can offer, and something every man must strive for and succeed in—And we wonder why suicide rates are so high among young men.

Patriarchy harms men by teaching them to suppress their emotions. They are told early on to ‘man up’ and that ‘boys don’t cry.’

VAW is inherently linked with cultural beliefs and traditions. It can be interpreted as a by-product of cultural norms and values, which are passed down through generations. Woman-hatred is found in culture, in the language we use, and in the arts.

The fact that this violence is still at times condoned by society, not seen as important as other forms of violence, or even as much of a priority as other issues within society, is unacceptable in the 21st century. When 47% of survey respondents in Malta believe that ‘women often make up or exaggerate claims of abuse or rape,’ and 38% believe sex without consent (which is rape) is in some situations justified, we (should) know that there is a serious societal problem.

Our public discourse needs to be addressed. The language we use matters—whether in the media, in everyday life, or from people in a position of power—it matters.

If it is deemed acceptable to use derogatory terms in reference to women, then this is proof that women are still not on par with men. When men who are sexist, who publicly denigrate women, who are sexual predators and are even accused of sexual assault, are elected to positions of power, including as heads of state, it sends a strong message to the public—discrimination and VAW are acceptable. When acts are normalised, they become approved.

The State and Violence against Women

Gains in women’s rights can never be taken for granted. It is clear that there are those who will do their utmost to push back women’s rights, including (or especially) our bodily autonomy. Indeed, some of the advances made by feminists towards gender equality and violence elimination are under threat or have even been eroded.

In 2017, Donald Trump re-enacted the global gag rule, which prohibits foreign NGOs receiving US funding from providing abortion services or even referrals, a clear attack on women’s rights. Who can forget the photograph of Trump signing the global gag rule, surrounded by seven (mostly middle-aged) white men?

That powerful image is what patriarchy looks like. It reinforces prevailing gender norms. Would we ever see a group of women signing off a law regulating men’s reproductive organs? Representation matters. Having women in positions of power matters. Is it only feminist analysts who treat male violence towards women as a global crisis? States have not yet taken VAW seriously enough, and their inaction perpetuates it. State inaction cannot be excused.

Nevertheless, we cannot simply say that the problem is that of patriarchy. This might be construed as absolving individual men of all responsibility for the violence they inflict. Perpetrators would then reiterate that they are innocent, because after all, it is society’s fault. Individuals do need to be held accountable for their actions, and impunity needs to end.

If individuals have absolutely no choice and patriarchy is solely to blame, then why don’t all men commit acts of VAW, and why do some women participate in violence as well? But, focusing on individuals without looking at the broader picture solves nothing. Institutions, as well as the state itself, also need to be held accountable, because VAW, on such a large scale, is failure of society as a whole.

Institutions, as well as the state itself, also need to be held accountable, because VAW, on such a large scale, is failure of society as a whole.

And yet, in a capitalist, neoliberal world, does the state really care about its citizens? Or do we need to frame VAW in terms of economic consequences for states to take it seriously? In other words: if you do not really care about the well-being of women, at least eliminate it for the sake of the economy. And failure to address VAW has serious economic consequences.

A high percentage of the cost of domestic violence is associated with domestic violence against women. This is due to a number of reasons, such as the fact that there are more women than men who are victims, and because women are subjected to more frequent and severe attacks, suffering more serious injuries than male victims. In 2008 in England and Wales domestic violence cost the state £3.86 billion, including criminal justice, health care, social services, emergency housing, and civil legal costs.

If human and emotional suffering are included, the amount rises exorbitantly. The most recent report estimates that the social and economic cost for victims of domestic violence for one year is £66 billion. This, in effect, puts a price tag on domestic violence, and can (unfortunately?) be politically important. If governments looked at the economic cost of VAW, they would realise that allocating adequate resources and funding to address and redress such violence is actually cost-effective.

However, if states are trying to tackle VAW for the wrong reasons (and not because of women’s humanity), will it help us reach gender equality? How can women participate in the public domain, be in positions of power and authority if they are dealing with health problems due to domestic violence, sexual assault, or any other form of violence?

How can women participate in the public domain, be in positions of power and authority if they are dealing with health problems due to domestic violence, sexual assault, or any other form of violence?

Democracy—the inclusion of women—increases violence regulation and decreases its deployment. But women are still held back because they face a barrier that has yet to be broken. Unfortunately, the state itself enacts certain forms of VAW via its subsidiary bodies, both through action (e.g. sexual abuse in governmental institutions) and inaction (e.g. lack of abortion care), which can also be described as symbolic state violence.

Religion against Women’s Rights

The contemporary state does not have a monopoly over ‘legitimate’ violence. This authority is shared with others, for example the catholic church. Although there has been progress in the work towards gender equality in the past few decades, there has also been a roll-back of women’s rights. Religion is a major institution that seems adamant at revoking global gains, pushing women back into the trenches, and doing its best to keep them there by burying them alive.

All major world religions are patriarchal; vehicles for the subjugation of women, preserving gendered social norms. In a way that seems almost hypocritical, some religions have rejected feminist thinking so powerfully, as to have propelled themselves even further away from equality, and have become, ultimately, fundamentalist. And what all fundamentalist religions have in common is this: their need to dominate women even more wholly.

In countries where religion still has an enormous influence, the shackles are very difficult to break. The catholic church does not allow women into positions of power; they cannot be ordained. Some priests have been known to tell women in abusive relationships to make amends; that there cannot be rape within a marriage, as it is the wife’s duty to be sexually available for her husband.

Catholic doctrine does not allow the use of contraception (let alone abortions), urging procreation, and thrusting women into multiple (wanted?) births.

Catholic doctrine does not allow the use of contraception (let alone abortions), urging procreation, and thrusting women into multiple (wanted?) births. Women cannot achieve economic equality if they cannot exercise their reproductive rights. Men’s patriarchal obsession with female reproduction locks women within their bodies. Our bodies are treated as though they embody the morality of the entire human population.

Violence against Women Can Be Eradicated

In a world replete with violence it almost seems a normal part of life; it appears inevitable. Yet VAW is neither inevitable nor impossible to reduce and eventually eliminate; with the vital will and necessary resources, this can be achieved.

Experience shows that people can be mobilised to overcome violence in all its forms; men are necessary allies in this collaborative effort. To address VAW it is vital that women are involved in policy making. It is especially important to have a diversity of women—women of different ethnicities, classes, ages, sexualities; women who are victims/survivors of the violence and abuse that needs to be eradicated; women’s groups and organisations that work with victims/survivors; and academics who study these issues.

All of humanity would benefit from an end to VAW; and so, I ask—When will women finally be human? When?

Leave a Reply