Contrary to what many want to make us believe, this republic is far from immaculate. Acknowledging this might help us resist the dirtier among us.

by Kurt Borg

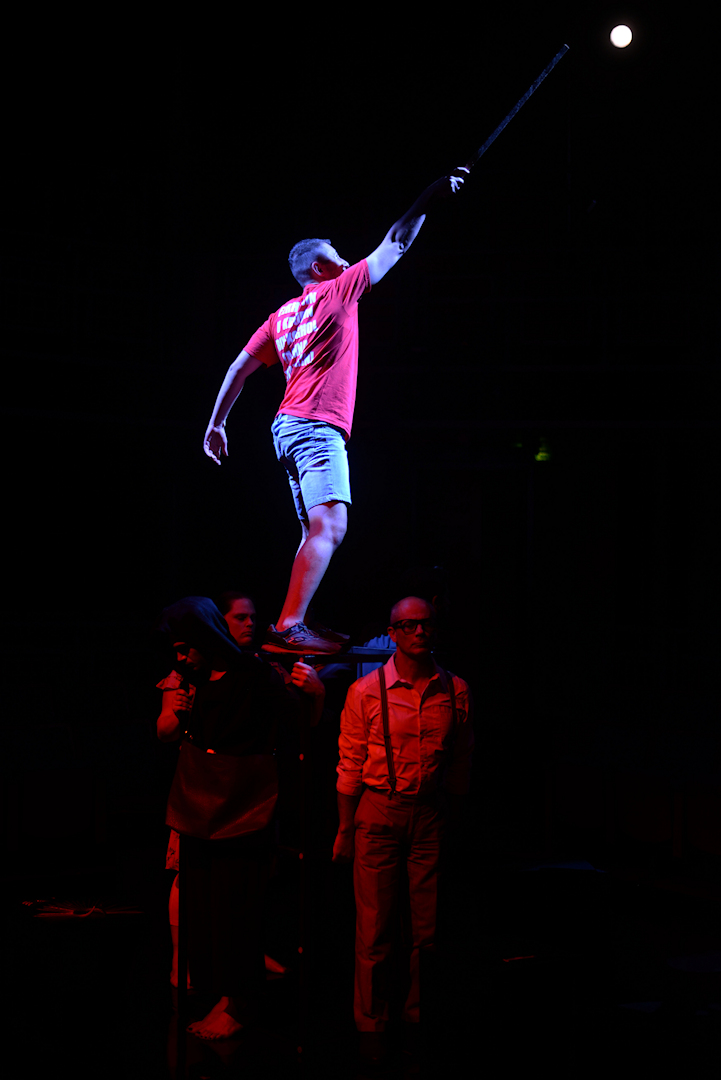

Image: Still from Repubblika Immakulata promotional video (amended)

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] General election, a wedding and the local feast. On the same day. Within the same family. No one wants to give in. And whilst everyone tries to hold on tight to the traditions that make us who we are, no one wants to accept that in Malta, we are no longer what we used to be.

So went the tagline of Repubblika Immakulata, the latest theatre production by Dù Theatre, written and directed by Simone Spiteri. RI is a political tragicomedy that provided a critical snapshot of contemporary Malta and was on everyone’s lips for this month. Well, not everyone’s; after all, the audience for RI was the typical Spazju Kreattiv crowd. So, no matter how well-written, smart and witty, it ultimately was a play addressed to people who more or less already agree with the play’s main idea: namely, that there are some dirty things going on in Malta.

Usually I feel that Maltese plays suffer most in the script-writing but thankfully this was an exception. The writing was flowing and scenes were well-executed, even if the second half was slightly dragging. This review will not discuss the plot and the characters in much length, but will engage and analyse some of the play’s main messages (*).

Online Reactions

Let’s start with some reactions to the play on social media (**).

Some hailed the play as required reading for the nation, suggesting that the play should be included in the educational curriculum. Others critically remarked that despite the sombre message of the play being very obvious, sections of the audience seemed to prefer laughing at the vulgar jokes. One viewer remarked on the slightly excessive parody on the “usual ħamalli” and “tal-pepe”, prompting the crowd to laugh hysterically at the cheap jokes.

These others felt that the characters of the play were too extreme (or, perhaps, intentionally clichéd), depriving the overall message of subtlety. Also, these others said that whereas the play did not hold back when it came to vulgarity, it still held back (censored itself?) when it came to directly mentioning specific political parties or politicians.

The scene which foregrounded the auctioning of a statue of Saint Mary against a background of the siblings deliberating the price for their father’s house highlights the complicated relations between religion, family and money in this island.

It is true that the point of the play was not to point fingers at a specific political party, lest it be unjustly labelled partisan, but also because the message of the play seems to have been more directed at a general political culture. On a more positive note, many praised the scene which foregrounded the auctioning of a statue of Saint Mary against a background of the siblings deliberating the price for their father’s house, highlighting the complicated relations between religion, family and money in this island.

Archetypes or Caricatures?

In an interview with Teodor Reljic, the playwright Simone Spiteri suggests that the main protagonists of the play were intended as archetypes. And perhaps it is for this reason that they appear too unrealistic or homogenised.

The three main characters are David [Mark Mifsud] (the next ‘big shot’ in politics, who schemes with a businessman in order to ensure his election), Franklin [Andrè Mangion] (a hardcore festa enthusiast, a seemingly shallow person whose meaning of life depends on the festa), and Petra [Magda van Kuilenburg] (a woman who feels pressured to marry despite her partner being abusive).

Tensions are high among these three siblings as their big day coincides: the election is being held on the same day of the village festa, which also happens to be Petra’s wedding day. For two hours, the audience lives through the various hassles these three characters go through as they juggle their personal interests with family expectations.

The play seems to suggest that, despite being excessive caricatures, the audience can relate to the characters. In fact, the play closes with another character (Anon; we’ll come back to him(?) later) “breaking the fourth wall” and asking the audience whether they could see facets of themselves in the different scenes. In response to the silence, Anon prompts the audience—asking “are you sure?”—wanting to suggest that we all form some part of this major hassle despite our not wanting to believe so.

Anon: A Buried Voice of Reason

Anon (excellently portrayed by André Agius) is an interesting character. His (I’m using a male pronoun, but the character was quite post-gender and it would perhaps make more sense on various counts to use the singular they) Anon-ymous character plays a liminal role, being both another sibling immersed in the plot, as well as a detached “voice of reason” who analyses what’s going on in the play and communicates directly with the audience. Anon is the voice of critique who—in a memorable scene towards the end—is buried by the rest of the characters who would rather not listen to critique.

In fact, whereas all characters seem to lack a sense of self-reflexivity and seem to be deeply immersed in their situation, Anon is able to consciously reflect on what is going on. For this reason, it is Anon – rather than any of the other characters—who probably resonates the most with the crowd since he is able to adopt a critical and ironic distance.

Anon is the voice of critique who—in a memorable scene towards the end—is buried by the rest of the characters who would rather not listen to critique.

At the risk of sounding patronising, it could be said that the play is hinting at a basic inability of the Maltese public sphere to reflect critically on itself without neither descending into a categorical snobbing of “anything Maltese” nor uncritically celebrating how awesome Malta is. In this land where, as Anon puts it, everything is seen as blue or red, nuance is seriously missing.

The “Bad Guys”

With that said, the play makes an important point on another type of character who is able to have a distance from the situation, albeit a very cynical distance. In RI, the character of Albert (portrayed in an annoyingly convincing way by Pierre Stafrace) represents the businessman who thinks—not inaccurately—that he can own the politician.

This is the character who—without any apologies to Marx—believes that beneath all politics lies economics, and thus uses economic power to influence political realities. These are the characters who think they’re oh-so-wise and that they can dictate matters “from behind the scenes” because they know better, and know how the crowd reacts, and they know “what’s what”. Albert is the kind of guy who, when shit hits the fan, will gather his people and figure out how to spin a story and fabricate matters; he will tell you exactly what the next move will be and the subsequent one. Even the politician bows down to Albert; whereas David patronises his siblings, he is as meek as a lamb with regard to Albert.

I confess that this is the aspect of the play which hit me the hardest.

These, to me, are the serious problems of this immaculate republic. The same person who said that RI needs to be required reading for the nation also recognised that this will never be the case since they will oppose it. This question of who they, the “bad guys”, might be is interesting. Although, theoretically, I know better than to impose such a moralising “good guys/bad guys” discourse, impulsively I think that perhaps we need not dismiss it outrightly.

The play made me reflect more on this: clearly, many people I know (activists, academics, ordinary folk, even some government officials) aren’t like the bad guys.

The bad guys are real estate moguls advising us ordinary folk that we’d be happier if we lived in smaller properties; the bad guys are those who do not understand why it’s ludicrous to suggest that it’s OK to rent out a room to shift workers for 12 hours, with tenants switching after 12 hours to make way for another shift worker; the bad guys are the businessmen-turned-politicians who are unable to differentiate the two (or, rather, see them as extensions of each other). The list goes on.

Must Critique Be Moralising?

RI tries to spell this out—albeit a bit ambiguously—in the culminating final scene, which consisted of a poetic and impassioned speech by Anon addressed to the audience (***).

The jury is still out on this final scene. “Perhaps a bit too preachy and spoon-fed,” some said; “absolutely necessary to the play,” others retorted. Some felt that the speech was too didactic and moralising, while others saw the scene as the crux without which the whole point of the play wouldn’t have come out well. I do not think that this speech was absolutely necessary.

Actually, I think that the same impulse of the speech could have been better distributed throughout the whole play (in the spirit of “show, don’t tell”) especially since, at times, it wasn’t always clear where the play was going ideologically. Except for the implicit critique of excessive construction and the obsession with raising towers, I think that without that final speech which spells out the play’s “agenda” a bit too clearly, I fear that the play might have lacked a solid ideological backbone.

Without that final speech which spells out the play’s “agenda” a bit too clearly, I fear that the play might have lacked a solid ideological backbone.

Without that speech, the play might have been another somewhat satirical portrayal of Malta’s quirks (in the vein of “haha this is how we are”) without digging deeper into how far the stench goes.

With that said, however, I was not irked by the final speech as it had a cathartic effect of hearing something most of us (at least, most of us watching the play or reading this review) live through everyday being vocalised in such an impassioned manner. The speech clearly foregrounds the severe contradictions Malta is living in. Here is a brief excerpt from the speech, where Anon refers to “Il-Malti”:

Li jisloħ rkoptu l-quddies imma jweġġa’ b’ilsienu lin-nies. Li jipprotesta l-moħqrija t’annimal imma ma jara xejn ħażin b’mitt refuġjat f’razzett jgħix qisu bagħal.

Anon’s speech goes on by turning the guns from these “hypocrites” to the audience itself. Anon discomforts the crowd by sarcastically saying that we all feel excused and exempt from this criticism since we’re all-too-pure and innocent, and not part of that dirty gang of Maltese. If anything, it is this sentiment which I think the play doesn’t get quite right. I do not think that the best reaction to the nasty national state of affairs portrayed in the play is to level the grounds of complicity as if we’re all equally complicit and guilty. Ultimately, social critique need not be an exercise in collective guilt and shaming.

However, the play does well in deconstructing the myth of Malta as naive, innocent, pure and charitable. We’ve grown up alright—look at us leading the way in Blockchain and crypto stuff; look at some of us excusing dodgy offshore financial arrangements because “after all, the country is doing OK”; look at some of us say that it’s understandable that people are tempted to continue building towers of apartments with ever-increasing rent prices “because that’s what everyone is doing”; “make hay while the sun shines”; “U ejja come on, you’re going to ask me these questions in the morning?”

The play highlights how there’s something very wrong in this normalisation of everything. Sometimes we feel the need to shout out “STOP ALL THIS”. RI hints at this frustration, not because it has its own clear political program to put forward, but out of a felt sense that there’s something ridiculously wrong with all this. However, this political rage has to be channelled outward toward the real targets and not internalised in order to send the audience on a guilt trip.

All in all, through its characters (and, sometimes, despite them) the play scores highly in its attempts to not just portray Maltese society through a critical lens, but also—in reference to the title of the play —to drive the point home that, contrary to what many want to make us believe, this republic is far from immaculate. Acknowledging this might help us resist the dirtier among us.

* For a ‘more standard’ review, see this article which gives a good account of the play, considering it’s Lovin Malta (I’m sure LM can take the jibe, especially after the parodic portrayal of them in Repubblika Immakulata).

** Most of the reactions to the play I mention here were obtained from Facebook. However, since I don’t consider informal Facebook statuses to constitute news items or official sources, I hesitate to identify these individuals or provide a link to or a screenshot to their Facebook profiles. With that said, if anyone reading this recognises their opinion being represented in this review and wants to be identified, do get in touch.

*** Many thanks to Simone Spiteri who sent me the text of this speech while writing this review.

Leave a Reply