“National Anthem”, a solo exhibition by Kevin Mallan is a verdict, a protest song and, in the artist’s own words, “an outcry for this island and what the order of the day has become to signify”.

by Raisa Galea

Image: ‘National Anthem’ by Kevin Mallan (detail, colorised).

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne of the most fascinating qualities of art is its openness to the world: anything, even the most trivial, most innocuous or the most atrocious events can inspire it. Art is a prism which absorbs the surrounding beauty, banality and abomination and reflects it in a structured and aesthetically meaningful way. It molds the chaos of our anxiety-struck existence into beauty.

In terms of its capacity to inspire art, Malta’s developers’ lobby deserves an award no less than Xirka Ġieħ ir-Repubblika—for the past few years, it has been the number one catalyst of creativity in the country. This statement could come across as bitter sarcasm, but it is so only partially: as our urban and natural environment is rapidly changing beyond recognition, Maltese artists are responding to the profit-driven chaos with striking projects. “In Between Obliterations” by Maxine Attard, “Ħaġraisland” by Isaac Azzopardi, “The Cement Truck Procession” by Margerita Pulè are but a few of the many artistic responses to the grim realities of an island-wide construction site.

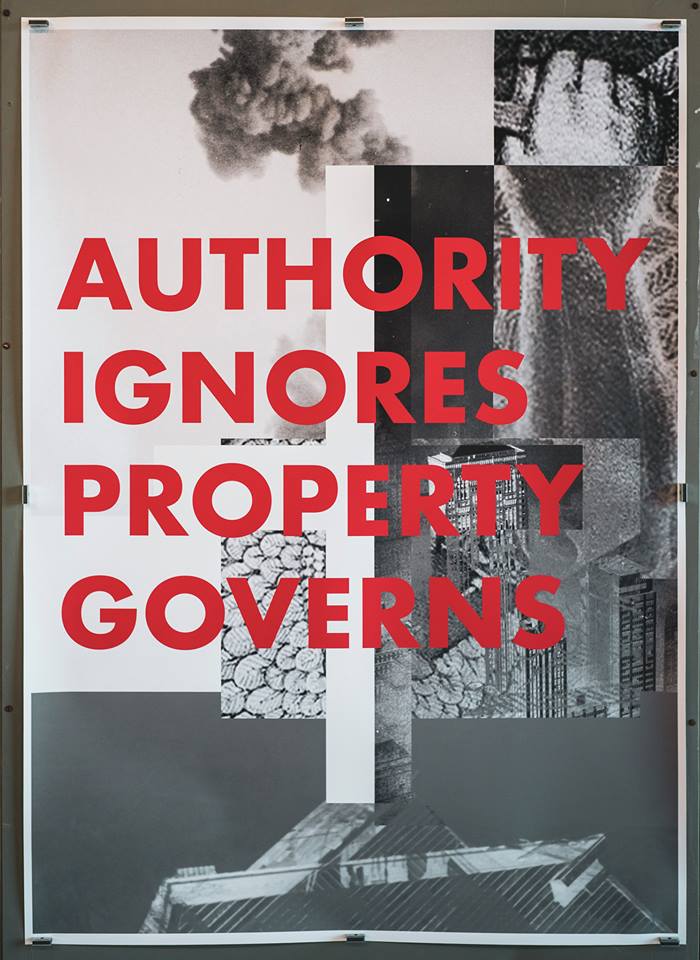

“National Anthem”, a solo exhibition by Kevin Mallan in collaboration with Friends of the Earth Malta, which was on display from 26 July to 3 August at Julian Manduca Green Resource Centre in Floriana, is a verdict, a protest song and, in the artist’s own words, “an outcry for this island and what the order of the day has become to signify”. As was the case with Mallan’s previous project “Landings”, the works are conducted as part of his Master of Arts Photography studies at Falmouth University.

On the one hand, the works reflect on the driving forces behind Malta’s ecological disfigurement in a dispassionate, almost clinical way, akin to a medical practitioner examining a critically ill patient. On the other hand, they expose the islands’ beauty, lost and remaining. The works are executed in the palette of Malta’s national flag: white, red and shades of grey, with snippets of gold, blue and—the most mistreated of all colours—green.

One of the installations features fifteen pieces of paper, neatly framing a Maltese passport, placed on a golden background right in the center of the work. This could be an improvised altarpiece representing the supreme religion of our age—the cult of the free market, which regards everyone as simultaneously consumers and products, irrespective of their religious orientation. Here, a Maltese passport is the ultimate symbol of faith—a crucifix of sorts—and a variant of Medieval indulgence: it is a passport to paradise on Earth, an absolution from the purgatory of border control and restricted freedom of movement, available for purchase at the relatively modest price of 650,000 Euro.

To the left of the passport, there are prints of areas defaced by development—Pembroke and Marsascala—sacrificial lambs of the God of economic growth. To the right—collages of city- and landscapes undergoing development. The top and bottom rows of the installation are idiosyncratic ‘psalms’ that pass a verdict on our dismal state of affairs: “You are the citizens of commercial production and false desires,” reads one. “Public means for private gains”, echoes another.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Here, a Maltese passport is the ultimate symbol of faith—a crucifix of sorts—and a variant of Medieval indulgence: it is a passport to paradise on Earth, an absolution from the purgatory of border control and restricted freedom of movement, available for purchase at the relatively modest price of 650,000 Euro.[/perfectpullquote]

Besides an altarpiece of neoliberalism, the installation could be interpreted as a notice board announcing recent economic developments and advertising the country’s assets for sale. A passport, a shoreline, a valley—all commodities waiting their turn to be converted into profitable assets.

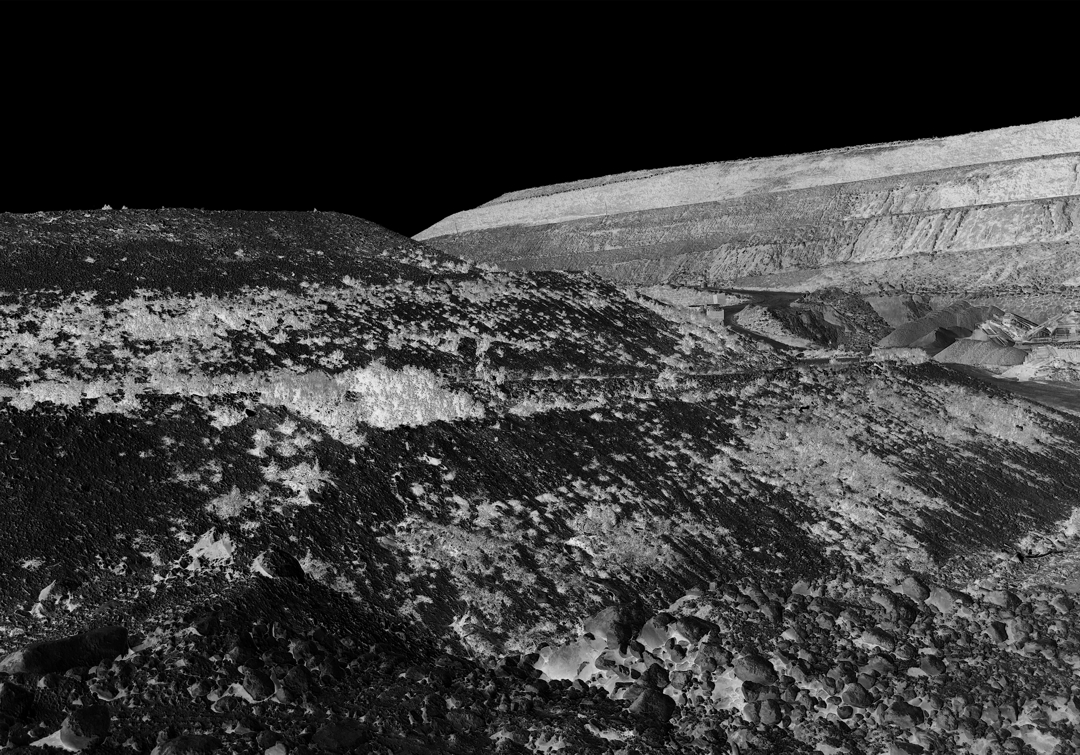

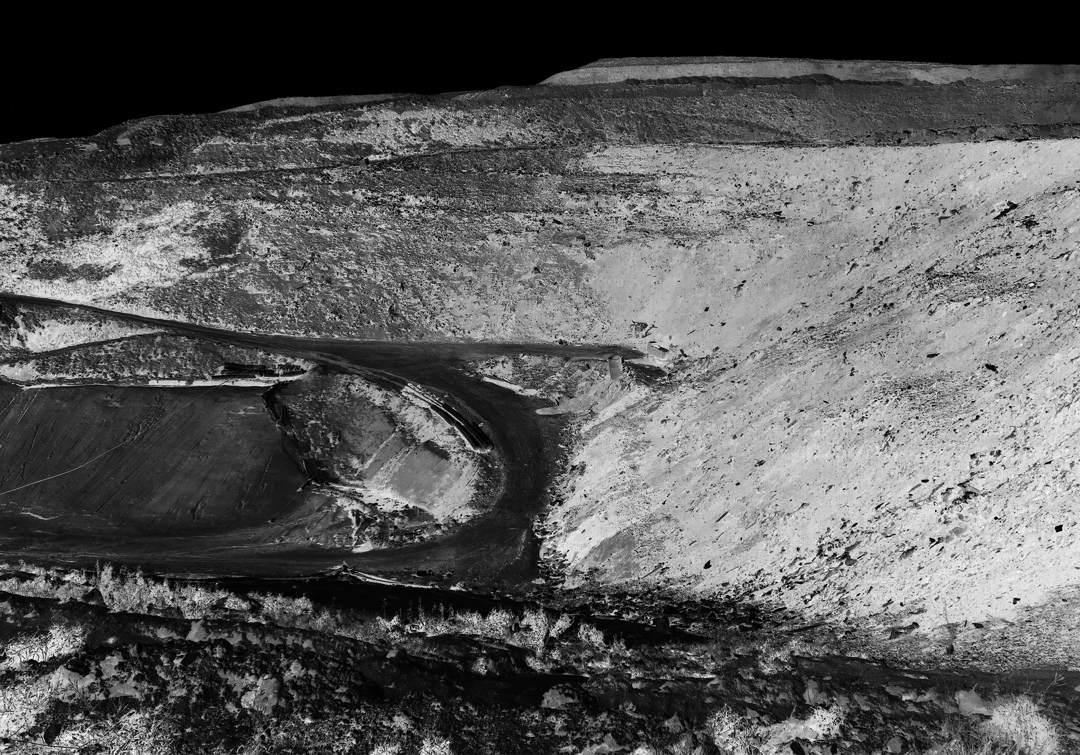

The imagery of the Magħtab Environmental Complex featuring in this exhibition resembles a lunarscape—a rugged, barren outline of a valley turned into a mountain of trash. Although the artworks expose the consequences of an economy based on mass consumption, the imagery is nevertheless strikingly beautiful. Ecological crisis can indeed be photogenic.

Right across the prints of Malta’s engineered landfill are images of Wied Għomor and the coast of Xgħajra, both earmarked for development. Viewed in that sequence, Magħtab’s lifeless sketch is a dystopian prophecy for the Għomor valley, which has been under threat of overbuilding for the past few years. It has been announced that the ruins of two houses in the valley, which were approved for rebuilding as two villas right before the 2017 election, are now on their way to becoming a 12-bedroom guesthouse.

The red-green palette of the prints is a flashing alarm bell, calling for our attention. Placed side-by-side with the blue-toned print of the sea off the Xgħajra coast, the colours allude to the bi-partisan consensus to give the green light to more ecological destruction of the country.

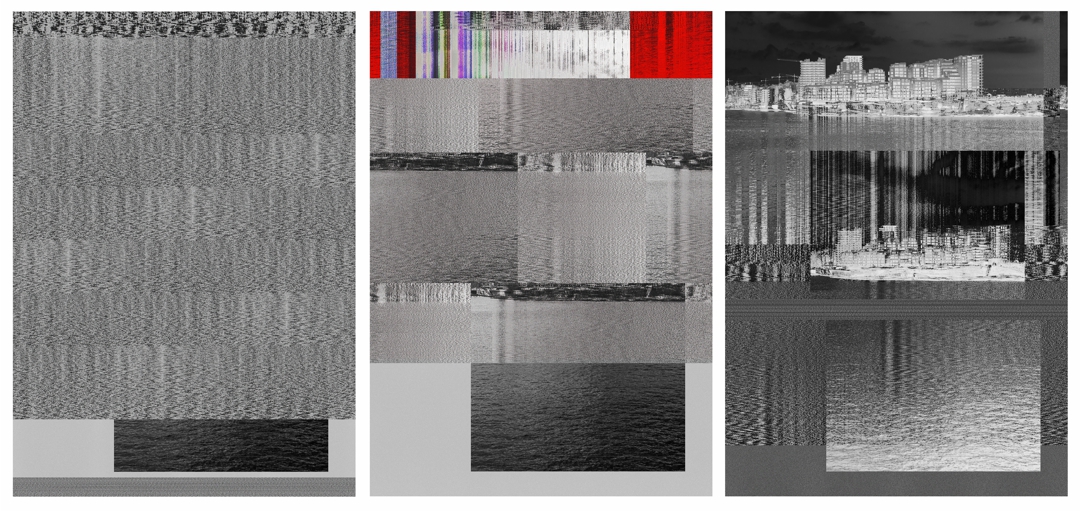

The most notable work, however, is the one the exhibition takes its name from—the ‘National Anthem’ triptych. On the right panel, photographs of Tigné Point and Sliema are passing through metamorphosis: they slowly break apart and dissolve into noise and which in turn merges with the surrounding sea. The central panel has the Maltese flag first dispersed into a spectrum of colours and then blended into a disturbed sea surface. The final, left panel depicts a series of horizontal strips of a noisy background. Is it sea surface? Or is it just noise? Is it construction noise or is it media noise in a country consumed by a storm in a teacup every week, hence unable to tell momentous events from trivial ones?

Either way, there could not have been a more accurate representation of a contemporary national anthem. Unarguably, noise is Malta’s national anthem in 2019. Also, it is no coincidence that noisy graphics blend so well with the imagery of the sea—the rising seas are on their way to reclaim their part of the Maltese coast, just as will happen in other parts of the world—that is, unless global capitalism, the rule of the golden passport buyers, is brought to an end in the coming few years.

]]>

By responding with art, beauty and civic concern to the chaotic and hostile environment of one of Malta’s most urbanised towns, Nimxu Mixja achieved the impossible. Even if for a brief moment, it reclaimed space from car dominance for pedestrians.

by Raisa Galea

Picture by Elisa von Brockdorff

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]y journey to the exhibition Nimxu Mixja—which was on display at the Mill, Birkirkara, until June 14—began with a walk. I walked along Birkirkara bypass, and instead of following the familiar route, decided to take a different turn. This improvisation led me to a part of Birkirkara I had never previously visited: I strolled past a baroque palazzo, an elegant chapel and a row of stunning townhouses before realising that I was lost.

After 20 more minutes of walking on narrow, often obstructed pavements, and twice being almost hit by a car, I finally found my way to the Mill. Getting lost and arriving on foot, however, was the best possible introduction to the exhibition, whose curators Kristina Borg and Raffaella Zammit are both aficionadas of walking.

As Kristina and Raffaella guide me through the exhibition, a photograph immediately captures my attention: a caterpillar of school students wearing bright-yellow safety vests walking on the pavement. Pictures of children usually elicit tender melodramatic emotions, but this one stirred a bolder feeling: it occurred to me that, although peaceful, a group of children walking on narrow pavements in a chaotic urban area of Birkirkara was similar to Gilets Jaunes rioters in Paris. In a car-dependent society such as contemporary Malta, a simple act of walking can appear as radical as a riot.

On second thoughts, there is more in common between Nimxu Mixja (a serene artistic project) and Gilets Jaunes (a raging riot) than a safety jacket: they both strive to reclaim civilians’ right to mobility. The Yellow Vests insurrection began as a protest of ordinary French people against the fuel tax which threatened to undermine their mobility. In France, the yellow vest was a symbol of disenfranchised residents of suburbs and rural areas who had to commute to cities on a daily basis for work and whose livelihood depended on the use of private vehicles. Nimxu Mixja participants, on the other hand, quietly reinstated pedestrians in a space suffocated by cars.

Walking as Artistic Exploration of Urban Space

Inspired by a spontaneous comment on social media back in 2017, Nimxu Mixja evolved into an elaborate artistic exploration of space for pupils of Birkirkara Primary School.

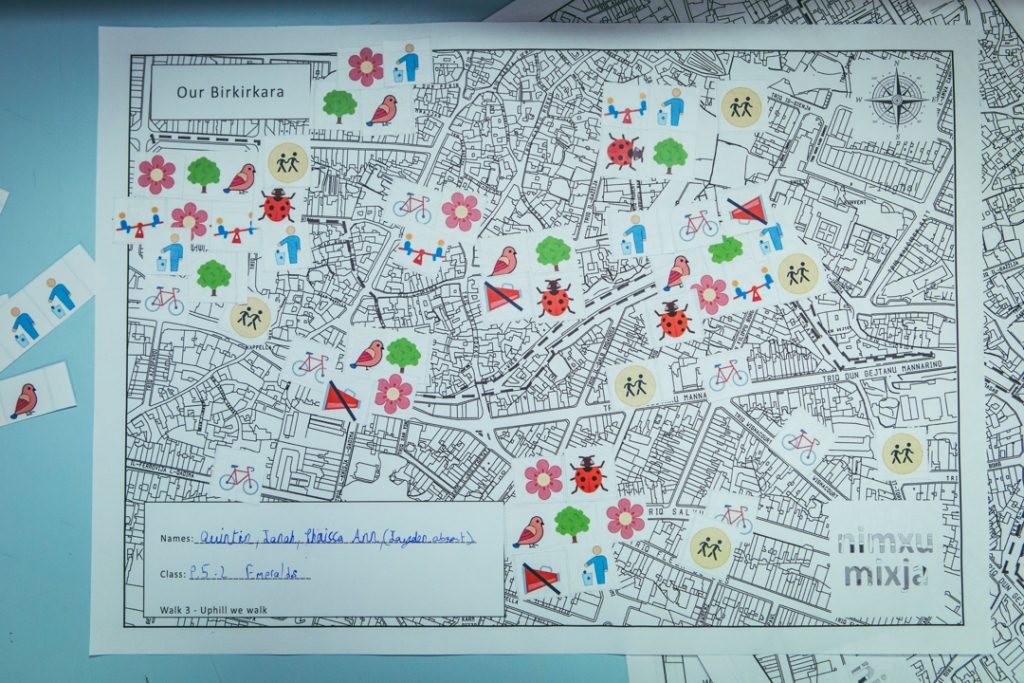

The project consisted of five sessions, performed separately for each of the four classes involved. The preparatory sessions focused on introducing the parents and the children to the concept of the project. The pupils’ initiation to Nimxu Mixja began with mapping their experiences of Birkirkara: they identified familiar places, nature, water and sites they considered as heritage.

Prior to the start of the project, walking did not occupy a prominent role in the children’s lives; they associated it mainly with a fitness routine and transportation, but did not deem it a pleasant activity in its own right. This perception of walking gradually changed over the course of Nimxu Mixja.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The children associated walking mainly with a fitness routine and transportation, but did not deem it a pleasant activity in its own right.[/perfectpullquote]

The curators designed five routes around Birkirkara to be explored over the six months of the project’s duration: four student walks, each lasting approximately an hour, and the final community walk that brought the students, parents and local community together. Keeping in line with the artistic dimension of the project, participants were encouraged to reimagine Birkirkara through the use of different senses such as sight, hearing and smell. Each walk also had a specific theme.

The first walk titled “Letting Go” took the children on an exploratory journey to places they had never visited or been completely unaware of. The variety of Nimxu Mixja’s positive outcomes absolved the many logistical challenges the organisers had to face. Seeking to expose the children to as many experiences and types of spaces as possible, the curators realised that there weren’t any accessible green public areas in Birkirkara, which is why the pupils were taken to St Aloysius’ orchard—a private garden belonging to the order of the Jesuits.

Curiously, bureaucracy made invisible boundaries between towns frustratingly tangible: Kristina and Raffaella could not obtain a permission for an excursion to a nearby public garden—whose guardian, too, seemed to be out of reach—that is formally assigned to Balzan, but can also be accessed from the Birkirkara side.

The two other places the pupils visited during the first walk were a scrap yard—an abandoned space hidden away from sight—and the Mill. Despite its location in close proximity to one of the busiest roads, not many participants were aware of the art, culture and crafts centre which was to host the project exhibition.

Themed “Lines and Shapes”, the second walk focused on various lines, shapes and patterns found in the newer and older parts of Birkirkara. During the third walk, the young pedestrians were taken on a tour through two distinct areas of the town and were asked to take note of their observations. They also walked along the valley watercourse that has been completely channelised.

The fourth walk (“Places and Our Community”) introduced the students to the place names and local history: they visited the old railway station, learnt about its history and walked along the former train track. This session brought the topics of history and mobility together: the children got to know about a different means of transport that existed in Malta in the past, but is currently unavailable.

During hands-on sessions, children reflected on the streetscape they observed during the previous day, each time expressing their thoughts in a different medium: the first walk transformed into poems in Maltese and English; the second—into improvised maps of the stroll’s route, which captured the young pedestrians’ sense of direction. The third post-walk session was an envisioning exercise for the children to imagine their Birkirkara, while the fourth and final session reflected on all the previous ones and developed into artworks expressing calls for improvement of the town.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The project ended with a bold exclamation mark: on Sunday June 2, 2019, the final community walk reclaimed one of Malta’s busiest transportation arteries from cars.[/perfectpullquote]

The project ended with a bold exclamation mark: on Sunday June 2, 2019, the final community walk reclaimed one of Malta’s busiest transportation arteries from cars. Kristina and Raffaella earnestly recall the genuine excitement of the strollers on that day: a few hundred people—adults and minors—arrived at the Mill on foot and bikes; accompanied by a few dogs and a pony, they marched in one colourful procession right in the middle of the busy Naxxar Road, which was closed to cars for the occasion.

The Many Portraits of Birkirkara by Young Pedestrians

Although walking on narrow, frequently obstructed pavements of an urbanised, noisy area may not seem an inspiring experience at first glance, Nimxu Mixija did splendid work on translating the children’s impressions into striking artworks. Not only do statements appear more powerful when expressed in poetry and graphics, they also inject beauty and thought into the otherwise plain discomforting urban architectonics.

With the assistance of renowned poet Miriam Calleja, every smell, every tactile and visual experience of the first walk was captured in poetry, written in either Maltese or English. Students pointed at and lamented noise, garbage bags and dog feces as most common features of the town’s pavements. They also struggled to spot nature. Bizarrely, as the children themselves put it, grass on roundabouts was their only experience of nature.

The second walk engaged the junior pedestrians’ sense of shapes, lines and direction. After having walked for an hour through the narrow lanes of Birkirkara’s historic core and the gridded modern districts, the pupils were asked to draw the route from memory; the memorised routes were then superimposed with the actual one. The session demonstrated the excellent orientation skills the majority of children possessed—skills they practically never have a chance of practicing since they are driven around most of the time.

Using the cameras in their school tablets, the pupils photographed the artifacts they encountered along the way—carved iron features of townhouses, railings and other decorative architectural features that caught their eye.

The slogan messages prepared during the fourth, conclusive post-walk session addressed their perceptions and concerns related to Birkirkara, and then were utilised as hand-held signs during the final community walk.

A sign stating “replace noise with flowers” immediately draws my attention. One may not think of delicate physical objects as a possible replacement for jarring sound waves, but this is where the artistic dimension of the project and youthful wit shine through. Despite its apparent naive cuteness, this piece of carton echoes the legendary “be realistic, demand the impossible” or, of course, “beneath the pavement, the beach” slogans of the May 1968 riots in Paris.

The outcomes of Nimxu Mixja offer plenty of food for thought. Prior to the thematic walks experience, nothing had challenged the students from growing up into another generation of car users. Since children are taken to school by car or school bus, they practically never experience their home town outside of a vehicle; areas that are only a few blocks away thus remain uncharted territory.

A society in which the simple act of walking feels as radical as an insurrection and where roundabouts are the only spots of nature ought to question its ways and means. Locked in airtight shells of schools, private houses and cars, deprived from any contact with the outside, the future generation of Maltese citizens are simply unaware of the loss of public, open, green spaces and heritage. Children or adults, how can we notice the disappearance of something we have never experienced in the first place?

Indeed, by responding with art, beauty and civic concern to the chaotic and hostile environment of one of Malta’s most urbanised towns, Nimxu Mixja achieved the impossible. Even if for a brief moment, it reclaimed space from car dominance for pedestrians. It introduced the town to its inhabitants. Most importantly, however, it carved an avenue for junior pedestrians’ civic expression which we all should pay attention to: let us, too, support the realistic demand to replace noise with flowers, as impossible as it may seem.

Nimxu Mixja was supported by Arts Council Malta’s Kreattiv fund. For more information and updates, follow the project’s Facebook page.

]]>

With a precision of scientific inquiry, the exhibition To Be [Defined] examines what it means—and feels like—to live as an antagonist in a story narrated by others.

by Francois Zammit and Raisa Galea

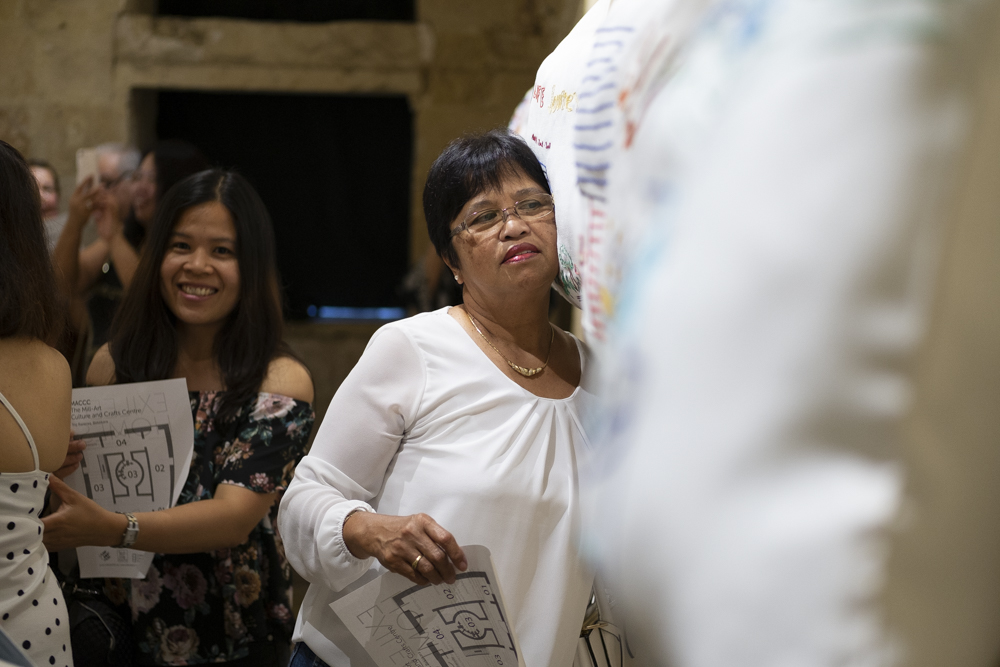

Picture by Alberto Favaro (adapted)

To Be [Defined] is not an ordinary art exhibition, if there is such a thing. It is not a fancy display of Instagrammable objects, neatly arranged at Spazju Kreattiv. The organisers—curator Virginia Monteforte, exhibition designer Kristina Borg, cultural advisor Alexandra Galitzine-Loumpet, project collaborator Sarah Mallia and strand coordinator Elise Billiard Pisani—defined it as ‘an artistic-anthropological exhibition dealing with past and contemporary displacement’.

Where does this description leave us?

Unlike the majority of conceptual and abstract artistic projects which tend to leave interpretations to the viewers, To Be [Defined] inscribes its message with a precision of scientific inquiry. By appealing to the aesthetic sensibilities of the viewers, the exhibition takes them on a tour de force journey through the experiences of exile which could only be interpreted in the context of grave institutional injustice.

The project does not seek to comfort the audience. The combination of hardship and beauty on display provokes outrage and begs for hope at the same time—both so vital to keep the spirit of solidarity and compassion alive in times of exclusion and apathy. The restriction of viewer’s interpretations is by no means a weakness of the project. By stating its message loud and clear, the exhibition still leaves a room for self-exploration. It poses four fundamental questions—Who are you? The one who defined? The one defined? The one to be defined?—which could lead to a surprising discovery of what it means to be who we are and who has the authority to shape our lives.

Who and What Defines Us?

Right upon stepping into the exhibition, the viewer enters a room split in half by a steel wire net. If one word could describe Do Not Cross by Alberto Favaro, it would be ‘precision’. The wire cuts through the desk in the center of the room, penetrates through the newspaper on the desk and passes through chairs. The net is light and, at first sight, does not seem to be a serious obstacle: the objects on the other side appear so within reach, albeit it is a deceiving impression. The borders, the work says, are for the people only. Bureaucracy, commodities, international sensations and data flows know no boundaries.

The Migration Objects Collective Project redefines everyday objects in the most inciting manner.

It is our memories, experiences and habits—not formal documents—that make us who we are both as a community and as an individual. Items like coffee makers, garments and other everyday paraphernalia are reimagined in a way that goes beyond their utilitarian and functional use. The ubiquitous espresso maker, found in every Italian household, is redefined as ‘a sense of home, memories, sharing’. The act of preparing coffee and the scent of the morning brew thus becomes a means of one’s memories and communal identity.

Within the same art piece there is a row of hanging clothes with a price tag attached to them. The tags, however, define a ‘human’ value and not the speculative market one. The scarf is ‘priced’ at ‘protection, warmth’—which, apart from being the practical purpose of the garment, also aptly describes the emotional dimension of the person wearing it. Just imagine the uplifting sensation that a warm woollen scarf can give to someone who is experiencing the freezing temperatures of a new land for the very first time?

In a similar poignant manner, sixteen miniature works in bronze by Katel Delia become historical artefacts; only Familja migAzzjoni–Legacy is not about a national or international history but a personal one.

In an equally touching and unsettling way these two exhibits invoke a familiar sensation we experience when looking at photos and personal items of our loved ones. In the object we recognise the person. And while observing the objects on display, we cannot escape the feeling of becoming acquainted with their owners and recognising our common humanity. Whereas the institutional discourse renders people as objects and numbers, the personal items preserve our individual identities. Living beings with memories and feelings cannot be reduced to statistics or administrative subjects, the project insists.

One of the most profound characteristics of the exhibition is that it does not draw a line between the experiences of Maltese and non-Maltese.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Maltese too were excluded from parts of Malta’s territory by the British colonial powers.[/beautifulquote]

The short autobiographical story, part of Exiled at Home by Giovanni Bonello, is a timely reminder that Maltese too were excluded from parts of Malta’s territory by the British colonial powers. As a young boy, he swam from Valletta to Manoel Island, only to be told to leave immediately by the British officers who did not empathise with the state of his utter exhaustion after crossing a stretch of sea. In 2018 this story echoes painfully. Many Maltese seem to have forgotten the meaning of solidarity and favour the idea of deportations. Manoel Island is in service to the moneyed multinationals, who once again define the rules akin to the colonial administration.

Defining Ourselves

In his poem La Malédiction (The Curse), Hassan Yassin deplores the tragedy and consequences of the dehumanising attitudes towards Africans whose presence on the Parisian streets becomes synonymous with dirt, ‘rubbish to be thrown away’. No matter how condemning and distressing, the poem gives Hassan a voice. He is no longer a passive victim, but a human being with a voice, willing to tell his own story.

Preventing us from telling our own stories is a means of stripping us from our very humanity.

By rendering a whole category of people voiceless, the state and its institutions succeed in defining them as non-human beings. They (we?) are effectively reduced to inanimate, lifeless beings who are as good as dead. The Dead are not Dead by Malik Nejmi responds to this horrific state of affairs. The video art piece is especially powerful because it gives the individual members of the Senegalese community in Firenze the opportunity to define themselves.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Nothing About Us Without Us is both an allusion to Christian charity which should apply to all equally and a question of whether the economic growth at the price of injustice has become Malta’s new religion.[/beautifulquote]

The mass and social media have been overwhelmed and oversaturated with the images of those who brave the perilous journey towards Europe and the West but the general public is rarely exposed to their own voices, and thus the human essence of these individuals. By making their voice heard, Nejmi has led the audience to acknowledge the presence and humanity of those who are left on the kerb of Western societies.

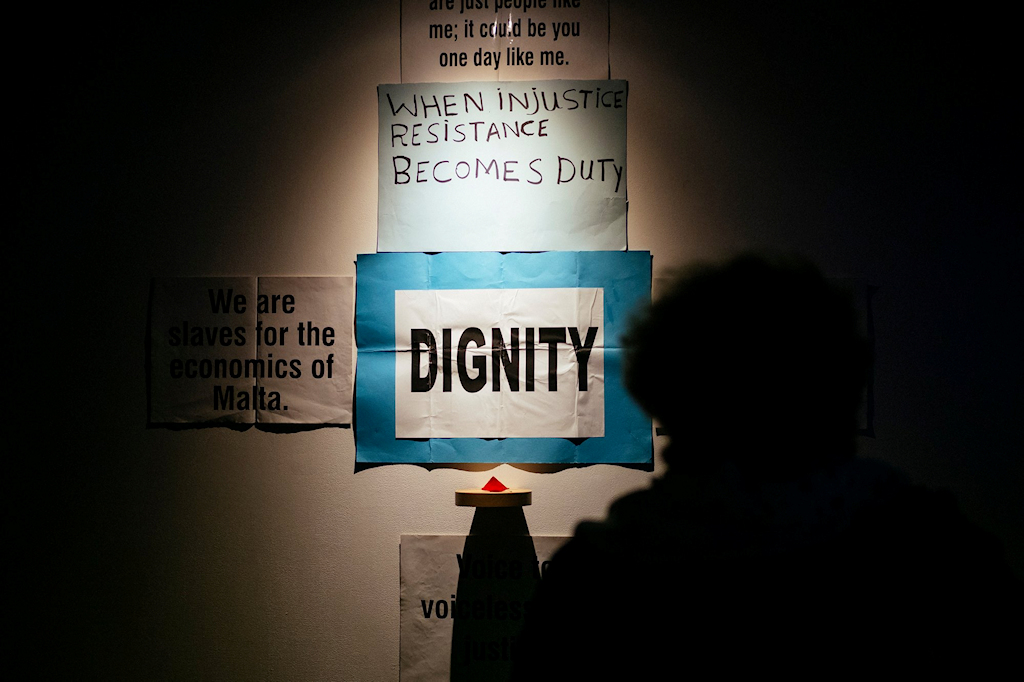

Another display, Nothing About Us Without Us, boldly confronts the audience with a rough reality that lies beneath Malta’s economic growth: the lives of poorly paid and mistreated migrant workers. In this opus the opinions of the workers resound black on white on placards which have been used during marches and protests in Malta. Together the statements form a shape of the cross: both an allusion to Christian charity which should apply to all equally and a question of whether the economic growth at the price of injustice has become Malta’s new religion.

![]()

After having been captivated, shocked, embraced and confronted by the stories on display, a viewer has no option but to question their own state of being and, more importantly, the role they play in defining and shaping the lives of others. The essence of To Be [Defined] is to examine what it means—and feels like—to live as an antagonist in a story narrated by others.

Let us too pause for a moment and ask: Who am I? What defines me? Am I the one who defines others? What responsibility do I have towards the others? Am I ‘the Other’?

To be [defined] is organised as part of RIMA project that articulates two main concepts about migration and exile: definition and construction on one side, and de-construction and resistance on the other. It features as part of the cultural programme of Valletta 2018, European Capital of Culture (Exile and Conflict strand, coordinated by Elise Billiard Pisani).

The exhibition is on display at Space C and Main Staircase, Spazju Kreattiv until Sunday, 4 November 2018. Entrance free of charge.

]]>

‘Landings’ is an artistic response to the outpouring number of petrol station applications, other deals with property, shoddy business and the issues of land use. Though enchanting and gentle, the imagery calls for public attention to the alarming appropriation of ODZ land for development and profiteering.

by Raisa Galea and Kevin Mallan

Image: Polaroids by Kevin Mallan (colorised by Isles of the Left)

Isles of the Left spoke to Kevin Mallan about his exhibition ‘Landings’ which was on display between 17 and 24 August 2018 at the Friends of the Earth Malta‘s newly opened Green Resource Centre in Floriana.

Raisa Galea: The theme of your exhibition is the impact of capitalist economy on the environment. Why did you choose petrol stations as the example to illustrate such an impact here, in Malta?

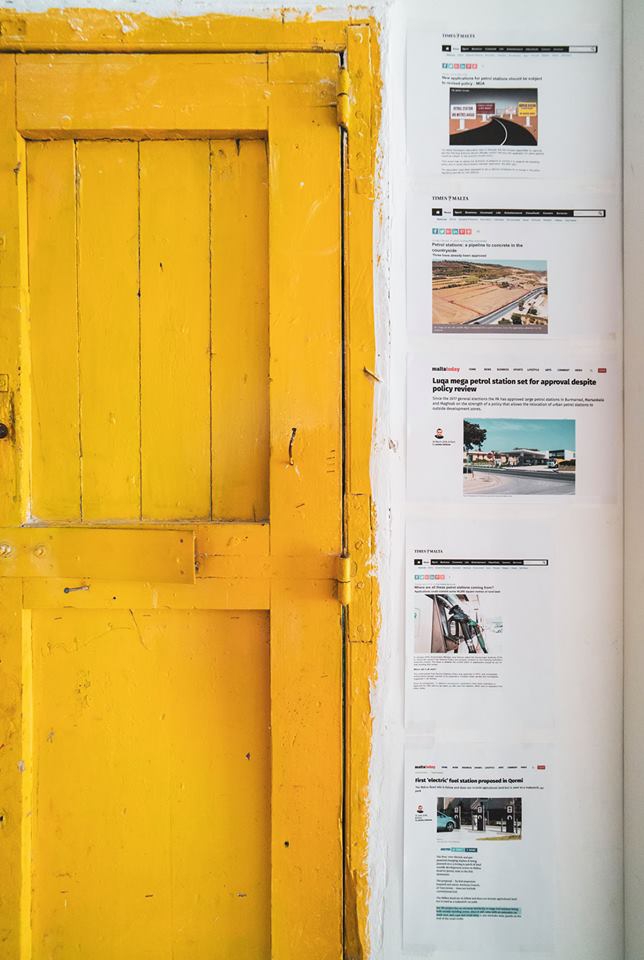

Kevin Mallan: The impacts could be rather abstract and intangible at times. Currently, there is focus on matters of land and ‘Petrol Stations’ are just one aspect of the ongoing work. This sub-theme stems from concerns relating to the subject. As seen, petrol stations’ applications have been on the increase with proposals on Outside Development Zones, following a 2015 policy approval that allows relocation of these structures to such areas.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Development approval of further petrol stations is quite ironic at a point in time when we are questioning transportation methods and looking towards zero-emission strategies.[/beautifulquote]

Although the infrastructural planning is far from ideal, the idea of having more petrol stations here is illogical. In a situation where you can find one at practically every inch of the island, does that make sense? Development approval of further petrol stations is quite ironic at a point in time when we are questioning transportation methods and looking towards zero-emission strategies. Although one might doubt a total phase-out anytime soon, it would be considerate to ask what is bound to happen in a couple of years’ time.

As is apparent, development of these petrol stations is providing an opportunity for large economic activity on what once was an Outside Development Zone (ODZ). Would these now provide an excuse for further development in the affected areas? Main concerns are therefore primarily related to land and further development. If the concerns fail to be heard, would that result in the extension of this conglomeration of buildings, not to mention other repercussions it could bring? You ought to ask, if so needed and if safe to do so, why don’t we upgrade existing petrol stations or utilise closed ones?

I think the answers to these questions are quite obvious to anyone who wishes to think thoroughly about the issue though, and they all seem to point to the same directions. Notwithstanding that, the exhibition does not seek to offer answers as such, but rather aims to raise awareness and push audience to think about the subject and such issues.

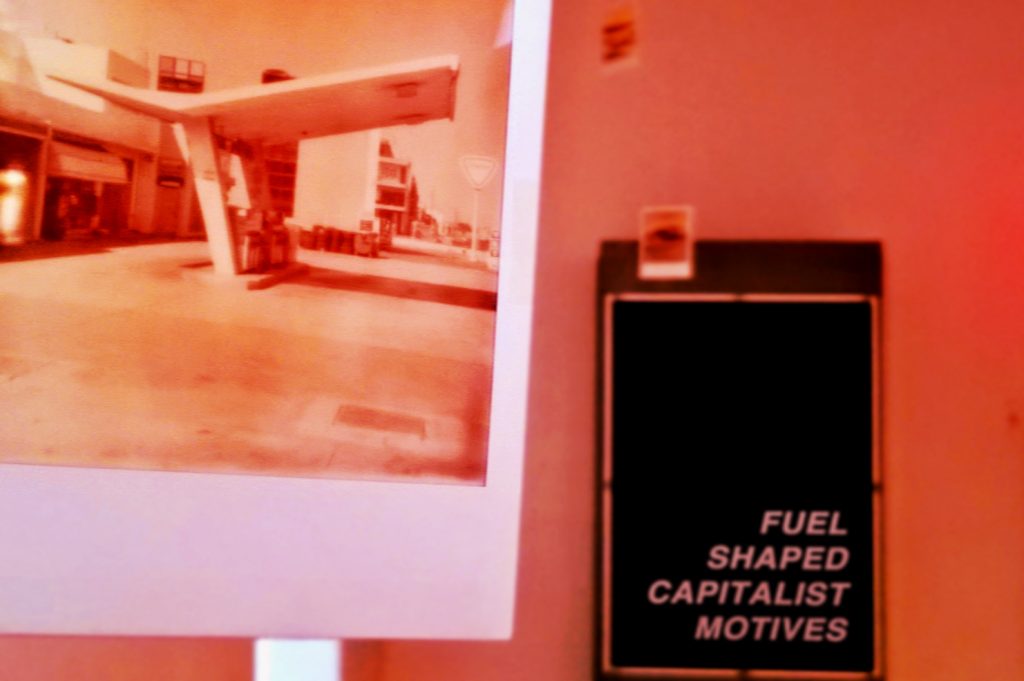

The working title of your MA Research Project is “Anthropocene—A Dystopian Legacy / Patria”. On the other hand, the Polaroid images of petrol stations are rather visually appealing. How does the exhibition’s imagery capture the links between the increasing number of petrol stations and the economic causes?

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]It could very well be “easier to imagine the end of the world” rather than other working alternatives after all, but amidst this, I wish that not all hope is lost.[/beautifulquote]

‘Landings’, the actual exhibition, offers a glimpse at some of the subjects currently being explored in my research project, which are not limited to ‘Petrol Stations’. Dystopia within this context does not refer to sudden catastrophic events but rather tackles the idea of what the supremacy of the current economic system alongside the human impact could lead to. It is a “slow” mundane process but it has been going on for years, and its repercussions are more visible now, in the 21st century. It will keep going, affecting our environment and other aspects along the way, unless better practices emerge. As some say, it could very well be “easier to imagine the end of the world” rather than other working alternatives after all, but amidst this, I wish that not all hope is lost.

The imagery in this exhibition is practically a work in progress, and the sub-themes aren’t fully resolved in that sense. Also, the title includes aspects of work which are not on display. For instance, this includes subjects of consumption and waste management. Some work was excluded in favour of recent images, a decision made to concur with current coursework. The imagery you are referring to forms part of a series of photographs that were used to document existing stations.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The display of this selection of work intends to show the actual amount of petrol stations one could find in a small stretch of land, which could perhaps be the initial step towards further questioning.[/beautifulquote]

The Polaroid was used as an alternative instantaneous medium. Although these were not made in a manner to look appealing, the images in the first room aren’t portraying the actual causes per se. Rather, these show a mundane structure mostly devoid of the social aspect, shot in straightforward manner, where the situation permitted. The display of this selection of work intends to show the actual amount of petrol stations one could find in a small stretch of land, which could perhaps be the initial step towards further questioning. Personally, it also serves as a means to support an ongoing analysis of a subject.

The series has reached over 70 unique shots and it’s not yet concluded. At the exhibition, the photographs were displayed in a manner that surround the viewer and a few steps away from that imagery are snapshots from local articles—an essential link that should guide the viewer towards the right context. A text-based work was included with the intention to invite the viewer to make further connections. The red lighting in the room was a warning symbol. In my opinion, all these signifiers are equally important and, even though photography is the main working medium, I don’t feel constrained to work within any of its confined borders.

Your photographic project is not abstract, it seeks to attract public attention to the environmental costs of free market capitalism, which currently reigns supreme in the majority of countries, including Malta. In your opinion, how does the Maltese artistic scene respond to these developments?

Where possible, my practice was subjected to an objective representation, but the project can also be viewed as a personal reflection. This time, due to the nature of the project, a wide audience is almost essential and naturally called for, and this somehow entails a viewing outside the confined spaces of gallery walls and commercial practices. Above all, the project seeks to question current practices, the outside relations, and how these can affect and alter our living, at times without us really noticing or caring much for something to be done about it, accepting that as the status quo.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]If we want art to serve one of its purposes, I believe we must then move on from conservative practicing stands and be critical of the systems we are in.[/beautifulquote]

If we want art to serve one of its purposes, I believe we must then move on from conservative practicing stands and be critical of the systems we are in. I haven’t really examined the situation, and although I have been following the art scene for quite some time, I wasn’t much involved in it from a practical standpoint. Also, I have to focus on improving my own art. Due to this fact, I cannot keep track of all that goes in the scene and I may not be the right person to criticise it. The scene seems to have garnered momentum though, but subjects and critical perspectives remain up for questioning with the objectification and commodifying of art still seemingly widespread.

I cannot be sure, but in part, we might be prisoners of our own circumstances, torn between what we stand for and the forced mechanisms of a powerful system, which can be both alienating and inevitable. I find that there are a few people who acknowledge the emergency of the situation, but that is not necessarily embedded within their artistic endeavours. Art can be engaging and it can educate, and I believe we must be critical of our situations and push towards a more democratic following, for which we are responsible. Regulative bodies as well as lack of proper education could also be acting as an invisible barrier constraining thought and action on these regards.

Kevin Mallan chooses visual art as means to investigate matters concerning consciousness, life and political conscience, often through methods that merge photographic practices with other media. He is currently at an experimental stage working on a research project for a Master’s Degree at Falmouth University. While the project examines society and the human impact on the environment in close proximity with the subjects of industrial development and global capitalism, the study predominantly aims to question socio-economic practices within the Maltese borderline.

]]>

The craft of embroidery transforms and embellishes the experiences of the caregivers: it evacuates them from the confines of the private household and turns into artworks accessible to the public.

by Raisa Galea

Photograph by Darren Aguis

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he arrivals of foreign caregivers—most of whom are women from Philippines—to Malta do not draw vociferous protests by enraged nationalists. Unlike the African migrants and refugees, whose distress is a regular feature on the front pages, these women are not on the media radar. Whereas the presence of predominantly male migrant workers in Malta is conspicuous due to their occupation at construction sites, street maintenance and other outdoor services, Filipinas are rendered invisible by the confines of domestic sphere where they are employed. Their experiences, therefore, remain unknown and their input into the Maltese society goes unacknowledged.

“Exiled Homes: Embroiderers of Actuality” is a project by Aglaia Haritz and Abdelaziz Zerrou, in cooperation with anthropologist Gisella Orsini, Elise Billiard, Sarah Mallia and supported by Gabriel Caruana Foundation. The project creates a space for the stories of community of Filipino care workers and home helpers in Malta. It also challenges the stereotype of docile, obedient performers of household tasks which Filipinas have become intrinsically associated with.

The exhibition, which is on display at The Mill until 13th July, consists of three sections: video records of the interviews with 6 Filipina workers, the embroidered cushions with a speaker inside and a video of 15 women singing the Maltese national anthem in Tagalog, a language of the Philippines.

In the interview Ritzel, Nida, Jenifer, Criselda, Lorna and Jazmin talk about why, how and when they came to Malta, whether they have any friends here and what they dream about. All of them share experiences in a casual and expressive manner, with no hint of hesitation, encouraging a sense of intimacy with a viewer.

Their stories sound similar: they all came to Malta to work as home helpers and to look after elderly persons, although two of them originally intended to work in the US and Italy. None of them knew much about Malta before setting foot here and their first impression of it was a surprise. Lorna, previously a factory worker who was notified about a job opportunity by a friend, says that Malta did not match her perception of a European country. “The airport is small”, she says, “there are no tall buildings or large shopping malls.”

Their impressions of Malta offer a glimpse of how a generic European country is pictured in the Philippines—an idea which the Maltese are mostly unaware of. The absence of prosperity symbols identified with Europe in the eyes of Filipinos, such as tall buildings and large shopping malls, suggested that Malta was an unaccomplished country. Their impressions have changed since then. All of the women grew to appreciate their second home country with time and find the quality of life in Malta decent.

Among their favourite characteristics of Malta are the weather and the people. Jenifer, Criselda and Lorna say they like the people here. Criselda adds: “Maltese are a very accommodating kind. My landlord even gives me clothes.” Nida’s experience with the first employers was not as elated: she was kept without a salary for three months.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Some of them left their children—still minors—in the Philippines in the hope earning a better wage than their home country could offer.[/perfectpullquote]

Their dreams are similar too. The women look forward to returning home, reuniting with their families and leading stable lives with no deprivation. Some of them left their children—still minors—in the Philippines in the hope of earning a better wage than their home country could offer.

Listening to the stories, watching these women smile, laugh, share their dreams, I could not help but notice how easily these experiences could be interpreted as a testimony to the European generosity and embrace of diversity. Don’t the Europeans, Maltese included, give less fortunate an opportunity to earn a living and have a more prosperous future? Subscribing to such a narrative would mean to neglect gross injustices woven into these stories, despite the positive feel they convey.

Anthropologist Gisella Orsini, who conducted the interviews, states that “the caregivers work 6 days per week, mostly 24 hours per day with 1 day off, and have 1 month leave per year, which is usually used to return to the Philippines.” Although their labour is physically and emotionally demanding, it is not sufficiently rewarded in monetary terms: they are entitled to the minimum wage (€735.63 per month at the time of the interviews).

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Domestic labour, poorly rewarded and largely underappreciated by society, still remains the lot of women—of those who are bound to perform it in the absence of other opportunities.[/perfectpullquote]

Another thought-provoking aspect of the project is how it exposes the contradictions in the contemporary Western perception of gender roles. On the one hand, the work these women perform belongs to the domain traditionally assigned to female family members. It used to be the responsibility of daughters, daughters-in-law and younger sisters to look after the elderly.

The contemporary Western society places different expectations on women: having a career outside of the domestic sphere has become a measure for success for them too. As more women in economically advanced countries, including Malta, are moving away from household tasks, their previous roles are outsourced to economic migrants, albeit female too. Thus, domestic labour, poorly rewarded and largely underappreciated by society, still remains the lot of women—of those who are bound to perform it in the absence of other opportunities.

The paradox, however, is that it is precisely these women who carry the weight of breadwinning on their shoulders—the role traditionally assigned to men. These caregivers, despite their low wages, are paying for superior education for their children and keeping their families afloat. And it is not only the closest family members who benefit from their labour. Elise Billiard, the project collaborator on behalf of Valletta 2018, in her essay “The Encounter” quotes Rachel Aviv: “Philippines […] receives more money in remittances than any other country except India and China.” Hence, these women and their feminised labour are also the most precious asset of the Philippines’ economy.

The discrepancy between a desirable career for women in the West and that in the Philippines, the input of women’s labour into the national economy all point to the existence of double standards for success: one reserved for the economically prosperous and the other for the rest. This project, however subtly, lays bare such social and economic inequality.

The key element of the exhibition—the embroidered cushions with a speaker inside—tells a story of each participant. The theme is a colourful blend of memories, associated with both Malta and the Philippines: sea, coconut trees, mountains, Maltese townhouses, luzzu boats, churches and airplanes that lace these remote landscapes together.

The craft of embroidery transforms and embellishes the experiences of the participants: it evacuates them from the confines of the private household and turns into artworks accessible to the public. Although the medium of embroidery as traditionally a female craft might further affirm the gender role of the caregivers, it carries another, radical symbolism. A stitch embodies a border and embroidery is an opportunity to define the boundaries by oneself—a privilege too many are deprived of.

The third section of the exhibition displays all of the 15 women singing the Maltese national anthem in Tagalog, a firm statement of being part of the Maltese society. Although Filipino care workers are seldom accused of stealing jobs of the locals— the idea of migrants as job stealers is very male—they too might come under attack of the nationalism’s rising tide. Singing the anthem might be an act of courtesy, however, I wonder whether the women need to prove the significance of their role further. What could be a better proof of their significance to Malta than the delicate care they give to the elderly? If these women perform the role of a close family member, they too are—should be recognised as—part of the Maltese society.

]]>

It is not the ‘ugly and stupid’ art that needs to be smashed and never sent for repair, but the insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

by Raisa Galea

Picture by the author

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ust as it happens with most topics in Malta—from over-development to fast food adverts—the disputes about the quality and the place of art in the society quickly become absorbed by customary narratives: partisan rivalry and the country’s purported status of the ‘citadel of mediocrity’. Despite their dull uniformity, these disputes are worth looking into—they could suggest how Maltese people tend to relate to each other and to the outer world.

To begin with, public access to the arts in Malta is limited: Only a few places such as Spazju Kreattiv at St. James Cavalier, Malta Society of Arts and MUZA (a project still in the making, previously known as National Museum of Fine Arts) welcome the general public—that is, the majority whose professional and consumption interests are not directly linked to the arts. Other than that, contemporary artworks are displayed at art events, of which there are plenty. Most frequently, art is showcased at private exhibitions and book launches which, by default, imply their secluded or commercial nature.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences.[/beautifulquote]

Engaging with the art at social events cannot be contemplative and serene due to the confines placed by an informal code of conduct that the attendees are expected to uphold. The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences. That turns events-going into a hollow performance aimed to affirm the social status of attendees which has little, if at all, to do with the art.

Artistic experiences in Malta are also profoundly shaped by the country’s minuscule size.

In a small, densely populated country, a person usually meets artists before their works, unlike in the majority of larger states where pieces can be seen as anonymous and independent from their creators. The proximity to the artists is more likely to separate the general public from the art. It either results in a few fan clubs surrounding the artist or, on the contrary, the audience rejects the works straight away because they are repelled by the artist’s persona. Had Picasso lived and created in Malta, with his reportedly bad temper, he would have never gained any recognition for his works locally, in such proximity to the potential audience.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Nepotism, patronage of the governing elites, the lack of transparency in the process of allocation of public funds all create an ambiance of distrust which does not help promoting the arts.[/beautifulquote]

The partisan rivalry pervades practically every sphere of the Maltese society and the public perception of the arts is no exception. Nepotism, patronage of the governing elites, the lack of transparency in the process of allocation of public funds all create an ambiance of distrust which does not help promoting the arts. For instance, given that the Chairman of Valletta2018 Foundation and its Artistic Director are both Labour Party’s appointees, the V18 activities are bound to be trashed immediately, regardless of their quality, especially by the PN’s die-hard supporters. A fair critique of patronage is then brushed away as ‘elitist’ (and this excuse is accepted, mainly due to the prevalence of conservative takes on art in Malta).

Thus, the layers of individual, partisan and class biases are the obstacles between the artworks and the public.

In such circumstances, open air art displays could have been a remedy. Anonymous and open for everybody to contemplate on, they could bring art closer to the public and enrich our daily experiences. Instead, once introduced to the public space, the installations are instantly seized by the ‘taste police’ who asses their appropriateness to represent Malta’s creative potential. Worse, if the artworks do not meet the expectations of this informal ‘ministry for aesthetic standards’, they risk to be vandalized.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Denigrating another is the easiest way to assert one’s own virtue and that is exactly what the members of Malta’s ‘taste police’ live for.[/beautifulquote]

Whether it is due to its provincial status or the remnants of colonialism, the cultural scene in Malta seems to be in a perpetual reaction to the label of mediocrity placed on it by a number of Maltese. To the ‘aesthetic police’, there can be one and only ideal of ‘Culture’—that of a cathedral of supreme sophistication whose doors should be shut for ‘tasteless plebs’. Denigrating another is the easiest way to assert one’s own virtue and that is exactly what the members of Malta’s ‘taste police’ live for.

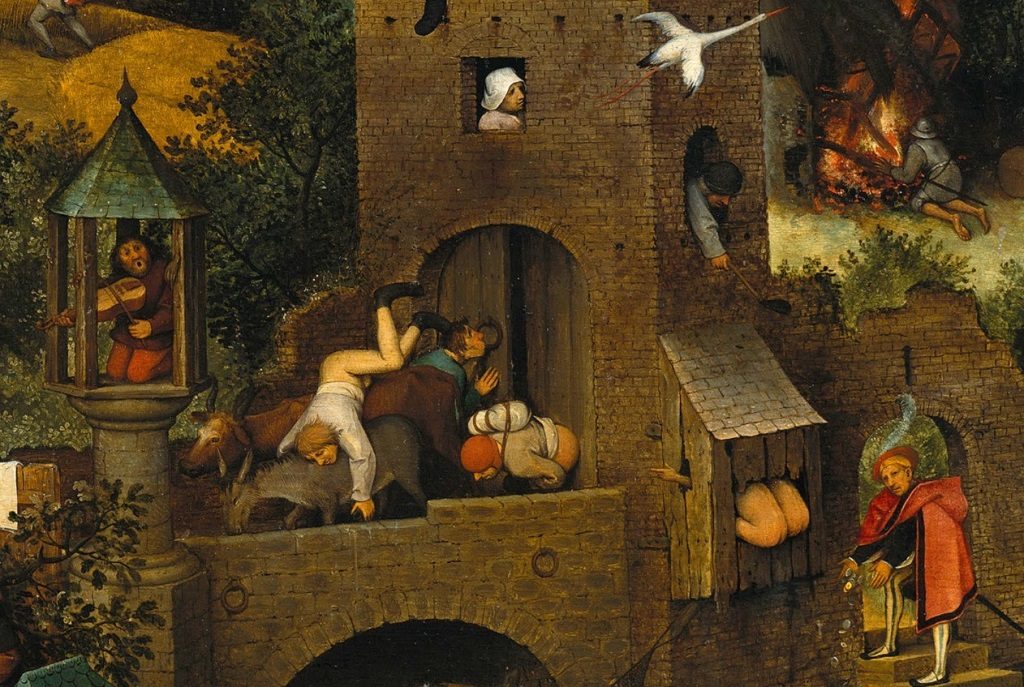

The eagerness of some individuals to stress their disdain for mediocrity reaches the level of absurd. I recall an opinion of a Maltese art enthusiast about Bruegel. Apparently, I learnt, the Flemish painter was a mediocre artist because his works were ‘cluttered’ and did not abide by the “less is more” dictum. Since not even Bruegel’s Dutch Proverbs seem to be up to the ‘standard’, the V18 Kif Jgħid il-Malti project which translated Maltese proverbs into art, was destined to insult the aesthetic sensitivity of ‘taste warriors’.

Habitually, the dispute focused entirely on the surface of the artworks. Their polystyrene medium was more worthy of a debate than their symbolic meaning. Hardly was it pointed out that the carnivalesque figures were well-timed to the Carnival—itself a feast of mockery and grotesque exaggeration. In my opinion, the project succeeded to achieve what it aimed for—the playful, quirky, cheeky and elementary outlines of these sculptures had brought the proverbs to life. The metaphors became tangible.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Those who ‘stick their nose between the onion skin’, who intrude into affairs of others, become tainted—and that is precisely what the sculpture conveyed.[/beautifulquote]

The sculpture of the man with the head stuck in the onion captured “bejn il-basla u qoxritha” perfectly well. Those who ‘stick their nose between the onion skin’, who intrude into affairs of others, become tainted—and that is precisely what the sculpture conveyed. It carved out the image of a gossiper. It ridiculed the intruder. It need not be more sophisticated because the proverb itself is coarse and direct. And, I believe, its honest primitivism surpassed the unimaginative critique that denounced it.

It seems plausible that the ‘folk crudeness’ of these sculptures alone was capable of provoking fury, leading to vandalism. It could be that the ‘taste warriors’ volunteered to swipe the European Co-Capital of Culture clean of ‘jablo junk’ a few hours after it had ‘contaminated’ Valletta. Bizarrely, the move was applauded by Mark Anthony Falzon, a prominent intellectual, who stated that “the vandalism of stupid ugly things in public spaces is not in the least distressing”. I hope that insecure conservatism that judges the art entirely by its surface appeal can also be considered ugly and stupid. That way it can be smashed and ditched straight away with no apologies offered.

When public art displays—sophisticated or crude—are scarce, having more of them is vital. Let them be ‘beautiful’, ‘ugly’, ‘noble’ and ‘profane’. Simply let them be.

Perhaps they succeed to stir curiosity and spark a few conversations. One day, these conversations will delve into symbolic meanings and wake the ephemeral beauty deep within each one of us. But first, the public needs to acquire safe access to the art; and the open air installations are fit for this mission best, because they create a space free from the partisan and social class confines. This democratic access to the arts, too, must be guarded from the dominant conservative perceptions that infinitely seek to segregate the ‘noble and beautiful’ from the ‘ugly and profane’. Valletta 2018 does not need more insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

![]()

The article borrowed an argument from the author’s earlier piece.

]]>