In the name of profit, various commercial interests are seeking to take away all that Valletta has to offer to the good of society. Any vision for a better city ought to have our common good as its main aim.

by Isles of the Left

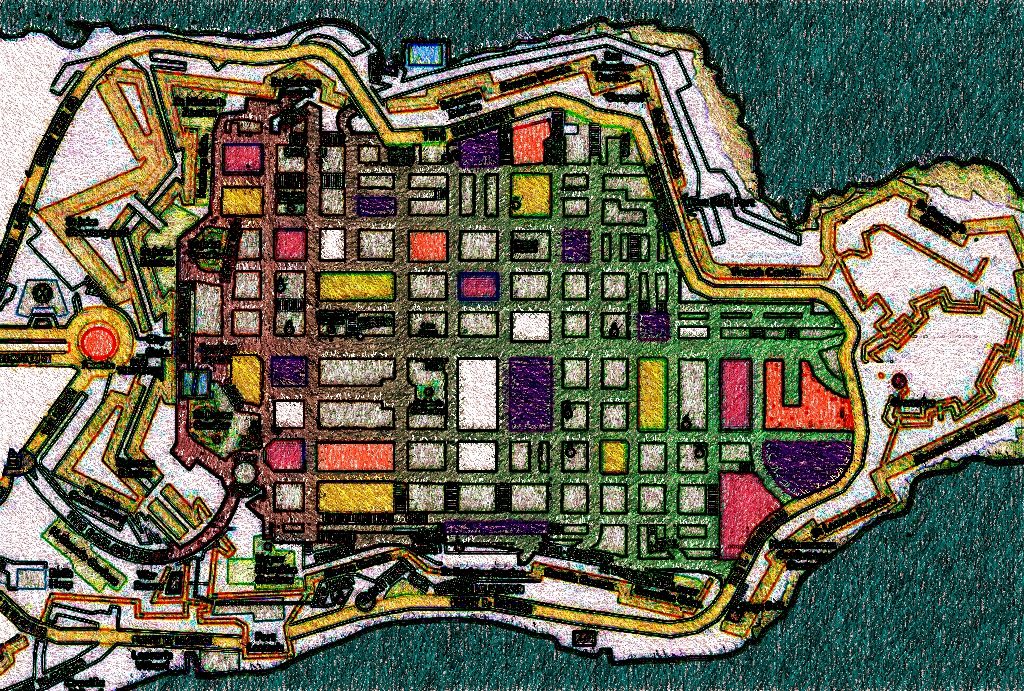

Image by Raisa Galea (assisted by Fotor & GoArt)

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]rom the privatization of the Valletta view by MIDI’s Tigné Point development to the obstruction of public space in Strait and Merchant’s streets by private enterprises, the thirst for profit appears to be rolling over any resistance in Valletta and beyond. However, this is only part of the story.

Resistance to the overtake of public space by commercial interests also exists. These initiatives are bold and courageous, yet seldom—if ever—are reported in the mainstream media. Thankfully, not everything and not everyone in our capital city have succumbed to the egocentric rationale of profit-making; there still remains hope in the shoreline of the Grand Harbour’s edge, largely untouched by mercenary ventures, in the projects such as MUŻA that aim to foster community engagement, and in the residents’ active resistance to the abuse of common heritage by City Lounge.

Isles of the Left has delved into the hidden politics of space. We discussed both the disappointing projects and the hopeful stories of resistance. This publication believes in the power of inspiring stories to encourage a different vision for the city—a vision that prioritises the common good of society over the thirst for profit.

Part I. A City by Gentlemen for Tourists

1. Valletta: A Capital of Whose Culture?

by Raisa Galea

Until a few years ago, Valletta was regarded as two distinct things: one a marvel of Baroque architecture and the other—a swamp. One to be admired, the other to be disdained and vilified. One—its facades and the other—its ‘3rd class’ residents. Elegant ladies and gentlemen frequently lamented that ‘a city built by gentlemen’ did not belong to ‘the gentlemen’ any longer.

However, il-belt has drastically changed in the past few years.

What’s happened? How has the capital so closely associated with ‘slums’, ‘criminals’ and ‘ħamalli’ become trendy and barely affordable for an average earner within just a couple of years?

The effect of gentrification brought on by the Valletta2018 handsome investment prospects is only a part of the bigger puzzle. The cultural climate of our capital is intriguing and complex. In fact, rather than having been revamped into a capital of culture, Valletta has become much more of a battleground of antagonistic cultures—and the winner has been the one that promises highest profit. Read more here.

2. How Neoliberal Capitalism Shaped Tigné Point to Sell the Valletta View

by Teodor Reljić

Certainly, the general public can still enjoy the gorgeous—and, crucially, tourist-friendly—view of Valletta from the Tigné Point bridge and the paved walkway that frames its posh residences and restaurants. But the presence of the residential and commercial complexes leave an undeniable impression on the experience—one feels as if they’re encroaching on somebody else’s land, even if they’re technically “allowed” to do so.

“In reality, part of the panoramic view has been commodified as a commercial proposition within this intrinsically financially-driven, property-led regeneration scheme, with much of the capitalised view accessible to a few wealthy residents able to buy into it.” Read more here.

3. The Politics of Space and Social Segregation

by Alberto Favaro

When the criteria for the evaluation of spatial planning are set by influential private actors, space is valued only as a financial opportunity rather than a livable place. It’s evident how an approach to the city that does not comply with this model loses any priority on the agenda.

As ancient Greeks once put it, we design the city and the city designs us. Therefore, territorial planning should be treated as a formative tool for helping us become the humans we want to be; any unequal opportunity at this stage will drastically increase the social segregation we are already experiencing.

Part II. Struggles for a Common City

4. Cities of the Future and the Power of Radical Creativity

Interview with Pascal Gielen

Pascal Gielen, Professor of Culture & Politics Sociology at the Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts, hopes that the cities of the future would be Common Cities, where social class distinctions would not be prominent and where creative communities—together with other people—would reclaim parts of the city from commercial interests. Read more here.

In her series titled “Valletta and Our Common Good”, writer and traveller Josephine Burden evaluated the flagship projects of Valletta2018. She also explored and mapped the activities which could help Valletta transform into a Common City.

5. Valletta and Our Common Good: Strada Stretta

by Josephine Burden

There are at least two practices that enable the aim of helping citizens to live well. First, good neighbourliness and the extent to which design and action take account of people. And second, the extent to which public space—the streets, squares, parks—enables human interaction.

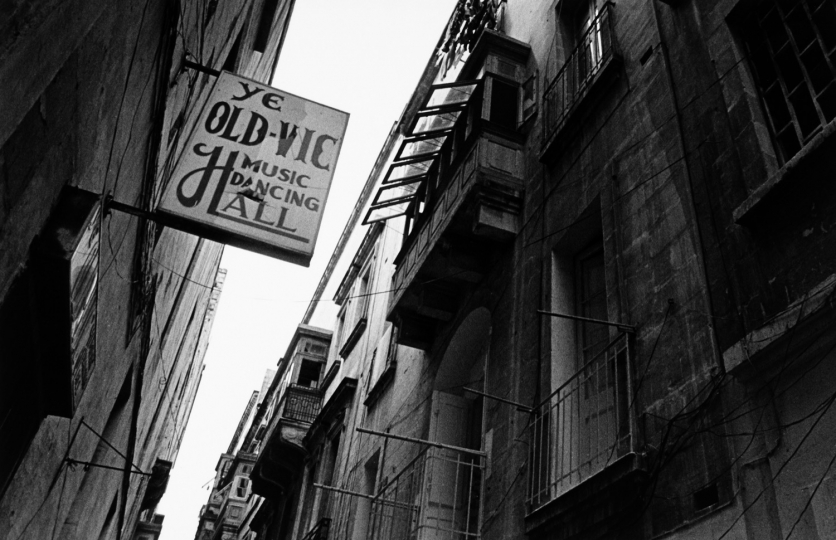

The legacy of Strait Street is mixed. The rash of commercial tables and chairs particularly around the junction with Old Theatre Street contradicts any legacy of public space as the lifeblood of citizen interaction. However, Strada Stretta also now offers creative and social venues that support civil action and innovative projects. Read more here.

6. Valletta and Our Common Good: is-Suq tal-Belt

by Josephine Burden

As we share the commons, we constantly negotiate our relationship in terms of the good that we hold in common. When one amongst us uses the commons such that the rest of us are disadvantaged, then our lives are diminished. Now that the market has been permitted to establish an abusive relationship to the commons and our institutions celebrate the right of Is-Suq to continue operating, I am discouraged about the options open to us in seeking to rectify the injustice. Read more here.

7. Valletta and Our Common Good: MUŻA

by Josephine Burden

In relation to Valletta Commons, MUŻA is a significant project, not least due to the planned openness to the community—by offering access from Jean de Valette Square through to Merchant St and by founding its curatorial practice in the stories of the community.

The re-launch of the Museum of Fine Arts as MUŻA opens up another aspect of the Commons and that is the role of our shared culture in shaping the way we think. As long as we leave it to others to tell the stories, we abandon the Commons to the dominant voices. Read more here.

8. Valletta and Our Common Good: City Lounge vs Residents’ Resistance

by Josephine Burden

We have yet to see if the growing chorus of voices seeking to strengthen the planning and enforcement system in Malta will have any impact. Some blame greed, corruption and collusion between government and business to enrich the few at the expense of the common good. Taking that position makes it difficult to identify possibilities for change.

Strengthening enforcement may help in the short term but we have to examine the underlying system that assumes that people in power—whether politically or economically—have the right to use public space according to their own needs rather than as a shared resource for us all. Read more here.

9. Valletta and Our Common Good: Biċċerija, Valletta Design Cluster

by Josephine Burden

This project adds another dimension to Burden’s concept of the commons—the criterion of process that takes account of the common good. She does not subscribe to the notion that the end justifies the means but she does hold that good process is more likely to lead to good outcomes. Genuine community consultation showcased by the Valletta Design Cluster gives promise of an end that will enhance Valletta Commons. Or perhaps the Commons may be considered as process rather than fixed product. Read more here.

10. Valletta and Our Common Good: Beyond the Pale

by Josephine Burden

Outside the walls of the city ‘by and for gentlemen’ lies a boundary space where ordinary people have more say in shaping the way we share the commons. The Grand Harbour edge of Valletta outside the walls has not yet succumbed to commercial exploitation. Perhaps it is the sea and the ferocious power with which she batters the exposed headland that will guard this part of Valletta for the Commons. Read more here.

Although this publication focused on Valletta in the past months, we have a keen interest in learning about initiatives that helped to safeguard common good from the profit-making interests. We encourage our readers to get in touch and share their stories.

]]>

Outside the walls of the city ‘by and for gentlemen’ lies a boundary space where ordinary people have more say in shaping the way we share the commons. The Grand Harbour edge of Valletta outside the walls has not yet succumbed to commercial exploitation.

by Josephine Burden

Image by Raisa Galea

My view over the breakwater is both changeless and ever changing. The sea will always be there. The lights at the ends of the twin breakwaters will continue to wink red and green. The bastions built by the knights will continue to mark the boundary between sea and land. Yet every day the mood of sea and sky changes, different ships and small boats move in and out through the harbour entrance, restoration work and changing use alter the bastion walls. The view from my window has become part of my understanding of continuity. The view is a marker of identity and existence. Yet my life is shifting, settling, finding new paths.

Middle Sea Dreaming: Short Stories on a Long Journey (pending)

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he location of Valletta on a peninsula separating two harbours is a major reason why I came to live here ten years ago. The city is hemmed in by defensive walls yet opens on three sides to shore and sea. Between the walls and the sea lies an area of common ground that has been claimed by different sectors of the Valletta community for a range of uses, sanctioned or otherwise.

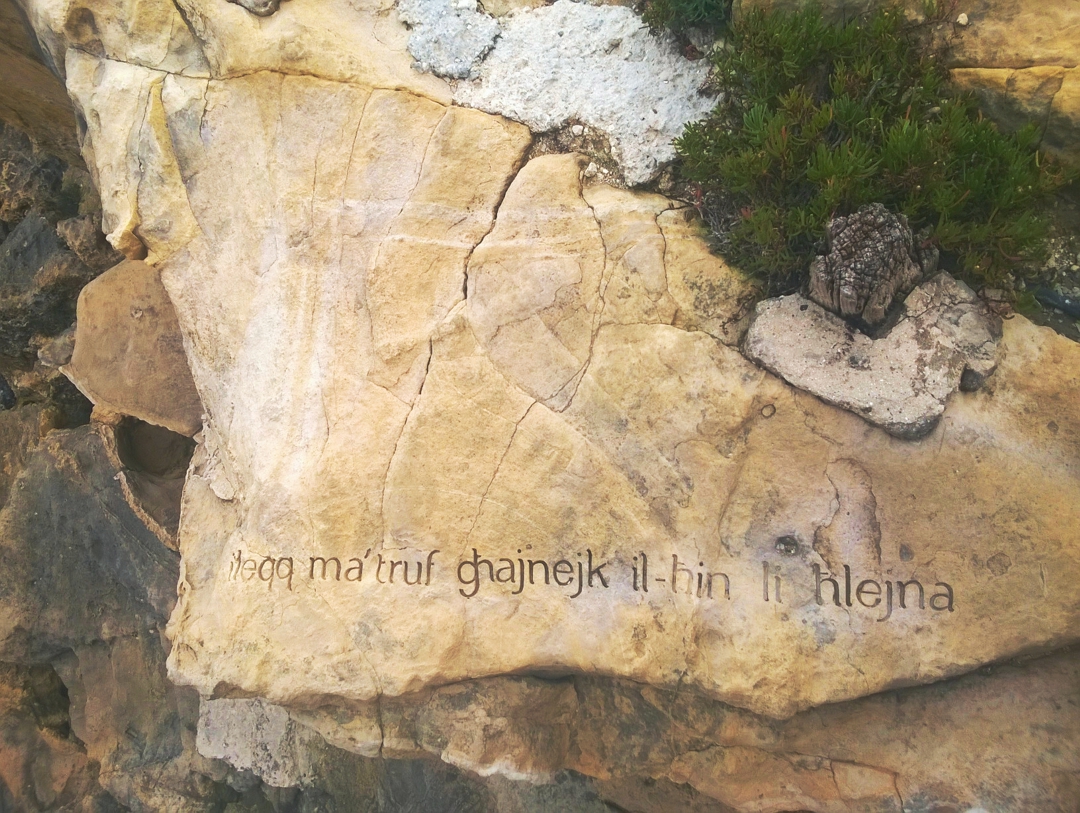

Walking the track outside the bastions, I have that rare sense of being ‘beyond the pale’ or outside the influence of the authorities that determine the spaces within the defensive bastions in the city “built by gentlemen for gentlemen”. Implied in that phrase, the exclusion of women and of ordinary Maltese from the Common Good of the city is brushed over as history. A few years ago, the phrase was swiftly removed from the side of the new Valletta community bus but I still hear it declared with thoughtless pride. “By gentlemen for gentlemen” denies the common good and sustains a view of Valletta as a gated community under the control of a narrow segment of the population.

Outside the walls lies a boundary space where ordinary people have more say in shaping the way we share the commons. Is sea and shore part of our common good?

Certainly, we have laws in place which require that the shore remains accessible to all. Resistance to the takeover of Manoel Island for development has secured an uneasy promise of community access, and some of our dismay in relation to the overdevelopment of St Georges Bay and Pembroke is related to our fear of losing the precious foreshore. Along with the countryside, the foreshore is central to the current struggle to retain citizen access to the commons.

![]()

Certainly also, people use the shore outside the walls to contemplate the horizon, fish and swim in the seas, walk to the ferry.

But what does it mean for the Common Good when three massive cruise liners enter Grand Harbour on the same day and pollute our air by burning heavy fuel oil to keep the air conditioning running for the passengers who are busy doubling the population of Valletta? How can we extend the Common Good of the ferry service so that other parts of Marsamxett and Grand Harbours are served? These are all aspects of this precious space outside the walls that we all need to negotiate as common good. But first let me give a sense of the place I am talking about. Here are more pieces from Middle Sea Dreaming.

I walk through the small boats and cats of the boathouse village outside the bastions of Valletta below my flat. I want to check out the new bridge to the breakwater that has been installed and is now lit up at nights in changing garish colours. A few weeks ago, I watched the new bridge lowered into place from my window. The barge arrived with the arched span from Spain where it was built in accordance with the approximate design of the old bridge that was blown up during WW2 when mini-submarines attempted to gain access to the harbour. I was elated by the precision of the operation and by the lap of honour undertaken by the Spanish ship on leaving Grand Harbour. The Maltese tugs and pilot boats tooted our thanks.

“Bongu,” I call to my neighbor who is out on the open space in front of his rooms drinking coffee. The boathouses in the village have been handed down through Valletta families for generations. At least two of my neighbours own a boathouse and spend most of their summer down there, swimming in the harbour and fishing from small boats. I envy them but know that it would be very difficult to find a way into this world of local knowledge and family inheritance.

I pause at the quay designed for the Boom Defense equipment. This defensive layer was added in WW2 by the British and involved a huge chain stretching across the harbour floor. If the harbour entrance was threatened, machinery housed in the Boom Defense rooms raised the chain to prevent access. A Valletta family now occupies the rooms and maintains the old war photos on the walls. Generations of old and young sit out on the quay in the cool of the evening. This morning I find only one man, working on his boat.

“Bongu.” I have been going to Maltese classes at the German/Maltese centre down the road from the flat. Progress is slow but some words derived from French or Italian come more easily.

I cross the quay and climb the steps to negotiate the rocks leading to a small footbridge. I pause on the bridge to contemplate the small jetty below, carved into the rock beneath the bastions. A canyon allows access to the harbour. The cave leads to a tunnel through the walls and perhaps into the city. The morning sun casts my shadow onto the back of the cave. The sea murmurs quietly in the tunnel.

The space I am describing is informal and the rules about how we use the space have been negotiated by the people who claim it.

In summer, I go down to swim and the Valletta Local Council puts down steps off the rocks to enable our access to the water. A few adventurous tourists venture down to Lower Valletta and take a cautious dip. But the Grand Harbour edge of Valletta outside the walls has not yet succumbed to commercial exploitation even though the restoration of the Mediterranean Conference Centre resulted in a nasty gash of spilled concrete down the bastion walls.

![]()

How are things working out beyond the pale on the Marsamxett side? Come with me to walk the shoreline on that side of Valletta.

Starting from the ditch outside the landward side of the walls and now straight-edged into formal gardens, we can walk down to the ring road, added by the British and cutting around and through the bastions.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Manoel Island is due to be built up by rich people for rich people; Tigne Point sells overpriced apartments on the strength of the view of Valletta from that side of the harbor.[/perfectpullquote]

Here, karozzin drivers pause to point out the view of Manoel Island and perhaps mention the Lazaretto where the gentlemen Knights quarantined people with leprosy. I do not know if the drivers also mention how Manoel Island is due to be built up by rich people for rich people or how Tigne Point sells overpriced apartments on the strength of the view of Valletta from that side of the harbor. On the Valletta side, the Grand Excelsior, now the New Excelsior hotel began this takeover of the foreshore for the exclusive use of those who can afford to pay.

As we walk down the ring road, we can look down on the ruins of buildings on the rocks of the foreshore. In summer, 2018, I realized how some of these areas around Marsamxett shoreline are used by Maltese families for swimming and picnicking. Kristina Borg’s fascinating project, No Man’s Land, curated by Maren Richter as part of Dal-Baħar Madwarha, used the borderline stories of people who lived around the harbours to inform a tour of the foreshores in an electric powered luzzu. The project also spoke to the possibilities of extending the ferry service.

Further on, the buildings outside the walls are well maintained and we can walk outside the road and behind the buildings to squeeze through to the ferry stop.

The ex-Police Station built by the British has long been converted to a restaurant although recent attempts to extend the seating area met with resistance from fishers and kayakers who also use that area. The adjacent ferry is currently being upgraded. This area was originally intended as the entrance to the Mandraggio, the Knights’ proposed harbor inside the bastions.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Plans are afoot to gentrify old water polo pitch and build a lido with commercial outlets.[/perfectpullquote]

Past the kiosk and restaurants, past the slipway where traditional lzuz turn their defiant eyes of Horus to the bastions, we come to the old water polo pitch, now forlorn and littered with plastic. Plans are afoot to gentrify this community resource and build a lido with commercial outlets on top of the existing low building beneath the road. I am anxious that we might see a repeat of the Capo Crudo takeover of the closed Valletta Regatta Club next door where an unpermitted, permanent covering has been added along with kitchen air conditioning ducts on the roof and giant gas container adjacent to the pedestrian area.

![]()

On the opposite side of the road, the bastions are honeycombed at the base by quarried rooms with metal doors. In constructing the defensive walls, the Knights quarried down into the softer layer of rock that is exposed on the Northern edge of Malta. The dry ditch thus formed is suitable for carving out spaces on either side to serve as air raid shelters or private rooms, and for the commuter road now used by city workers to park their cars. The softly eroded rock on the seaward side, capped with a layer of harder rock, now masks the horror of the view of Tigne Point across the harbor.

Around the corner, with our backs to Tigne, we pass Jews’ Sallyport, the backdoor, tradesmen’s entrance to the city, now significant as part of the linking routes around Valletta for both pedestrians and cars. This portal also links Biċċerija, the Valletta Design Cluster, inside the walls to the foreshore area and to Maori Bar, sometimes favoured by civil action groups for their meetings. The bar next door serves the fishing community that has grown up around the small boat harbor lined by metal and timber shacks. The restoration of the bastions threatened the existence of this informal group of fishers and galvanized their collective action.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]My hope lies with the sea and the ferocious power with which she batters the exposed headland and pours water into this stretch of the ditch.[/perfectpullquote]

Past the rock hewn baths on the left and around the corner, we are into hard rock shoreline once again and the original rough-hewn ditch of the Knights. Here the rock pools have been filled to smooth a passage for the heavy vehicles working on the replacement of the breakwater bridge. Again, I am anxious that this smoothing out may enable the extension of the road. My hope lies with the sea and the ferocious power with which she batters the exposed headland and pours water into this stretch of the ditch. Already the powerful storms have washed away the garish lights that embellished the new breakwater bridge.

![]()

You have now completed a full circuit of Valletta beyond the pale. Can we hold on to this space as a common good?

Already, the Marsamxett side of Valletta is compromised by cars and commercial outlets. Perhaps we can enlist the natural force of the sea to save the headland but we will have to be nimble and organize collectively to save Grand Harbour foreshore from cruise liners and commercial exploitation. The negotiation of the Commons is a continuous process and in future articles I will try and keep track of some of the shifts.

Read the previous chapters of the series here:

Part 1: Strada Stretta.

Part 2. Is-Suq tal-Belt.

Part 3. MUŻA.

Part 4. City Lounge and Residents’ Resistance.

Part 5. Valletta and Our Common Good: Biċċerija, Valletta Design Cluster.

]]>

Unlike Is-Suq, immediate neighbours of Valletta Design Cluster appear to be on-side and look forward to the proposed open access roof garden and possibility of finding artists on their doorsteps.

by Josephine Burden

Image by Raisa Galea (assisted by Fotor & GoArt)

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n one of the previous articles I wrote about MUŻA, in the hope that the relocated and renamed Museum of Fine Arts would fulfill its promise of opening to community stories and offering public access through the central courtyard—a significant linking space for us all to hold in common. The transformation is near complete and the new location opened to the general public in December. Ministers, Prime and otherwise, have lauded the project stressing the cost and the concept.

In his article “Project With People For People” Owen Bonnici, Minister for Justice, Culture and Local government, writes of MUŻA as “a hybrid of public spaces, galleries and retail facilities, equally relevant within one interconnecting weave that defines Muża as a national community art museum.” He adds: “Renovations to the historic building included provisions to ensure it is energy-efficient and has climatic control to protect the artwork on display.”

Therefore, MUŻA appears to embrace the idea of a linking space within the commons of Valletta and the Minister’s article draws our attention to another aspect of the common good, our shared environment.

The Minister does not mention names when he talks of “months of planning, meetings, discussions, restoration and branding” but I suggest that Sandro Debono, as mainstay of the project, and the many workers who have contributed their expertise and dedication to create a reality from an idea, must take credit for enabling government to celebrate important aspects of the common good.

![]()

So how does the fourth Valletta 2018 flagship project in this series—the Biċċerija, or Valletta Design Cluster (VDC) —shape up in relation to the added criterion of the environment as a common good?

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The aim of VDC is to set up an accessible space where creative professionals can work with each other and with the community.[/beautifulquote]

To date, we are only aware of preparatory process which can helps us assess possible legacy of the project. We know that the aim is to set up an accessible space where creative professionals can work with each other and with the community. I also know, from my experience of the process, that door knocking, artist and resident workshops, street meetings, site interventions and tours have featured prominently over the years since the project was announced.

I have participated in community workshops and street meetings where issues identified by the local community were compiled into a report and used to inform the process. At a following workshop with artists and cultural workers, we drew on this report to create interventions at the derelict site at the bottom end of Old Bakery St where it joins St Christopher St. The concept that informed the event was of an internal space that opened to the world beyond.

![]()

My contribution was to work with a film-maker and architect, Alberto Favaro, to produce a short video about attitudes to rubbish. I also donned my academic gown, embellished with party trinkets, and read from the report, framed in one of the windows onto the street. I wanted to express the thought that academic reports may sometimes moulder on shelves without informing action.

Genuine effort has been made to resettle the squatters who had set up home in the precarious building and to counter the inevitable gentrification of the area. Unlike Is-Suq, immediate neighbours appear to be on-side and look forward to the proposed open access roof garden and possibility of finding artists on their doorsteps.

Regular tours of the building have been offered for residents as the work progressed and workshops have been held with the Japanese design artist commissioned to bring the roof garden into reality. Links to other creative venues in the vicinity such as the Society for the Arts have also been forged and open up interesting possibilities in regards to the roofs of Valletta. I am a slightly more distant neighbour living at the other end of the street, but I have felt engaged and happy with the process. It is slow and the opening is delayed into 2019 but already the restoration is lifting the streetscape and I can include the route as my pedestrian access to Jews Sally Port and beyond to the Sliema ferry.

So the Biċċerija appears to be establishing spaces for artists to co-create as well as interact with the neighbourhood.

![]()

Cultural spaces that contribute to new thoughts and perspectives for artists and residents alike may become part of Valletta Commons.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Genuine community consultation gives promise of an end that will enhance Valletta Commons.[/beautifulquote]

Good neighbourliness through design and action, as well as enhanced pedestrian links, community access, and environmental consideration also appear to satisfy the criteria we have identified so far. But the project also adds another dimension to my concept of the commons—the criterion of process that takes account of the common good. I do not subscribe to the notion that the end justifies the means but I do hold that good process is more likely to lead to good outcomes. Genuine community consultation gives promise of an end that will enhance Valletta Commons. Or perhaps the Commons may be considered as process rather than fixed product.

I began this series by suggesting that I wanted to explore my own life as a process of action research alongside the concept of the commons in relation to the place where I live, Valletta. I framed the series by focusing on the four flagship projects of Valletta 2018: Strait St, Is-Suq tal-Belt, MUŻA and the Valletta Design Cluster and other aspects of the changing face of Valletta. I’ve identified some of the attributes of the common good that have emerged for me in the process of writing:

-

Good neighbourliness and the extent to which design and action take account of people.

-

The extent to which public space enables human interaction.

-

The intangible heritage of daily domestic life.

-

The contested nature of the Commons and strategies of resistance.

-

Shared stories as a common good that enables the flow of ideas.

-

All aspects of the environment as a common good.

-

The Commons as process.

Like all lists, this is incomplete and cries out for further exploration to enable the Commons of Valletta to continue flowing creatively. During the year of Valletta as ECoC, multiple projects have built networks between artists and between artists and communities. Some of them have sought to reimagine the spaces that surround and our identities in relation to others and to the environment.

I have focused here on the importance of the linking spaces within the city and between the flagship projects, to suggest that the legacy of Valletta 2018 is mixed and we still have a lot of work to do. In my next article, I’ll explore the boundary area outside the Valletta bastions as a linking space that is to some extent beyond the imperatives of Government and Commerce that construct and limit the Commons within the walls.

The Valletta Design Cluster. Work in Progress:

At the moment, The Valletta Design Cluster is still a construction site, but it nevertheless welcomes individuals interested in contributing to the project in the future.

![]()

Read the previous chapters of the series “Valletta and Our Common Good” below:

Part 1: Strada Stretta.

Part 2. Is-Suq tal-Belt.

Part 3. MUŻA.

Part 4. City Lounge and Residents’ Resistance.

]]>

For well over a year, City Lounge has abused our common good in order to increase their own commercial activity. However, citizens have not become used to the realization that one of our fellows is abusing the common good for their own enrichment.

by Josephine Burden

Image by Raisa Galea (assisted by Fotor & GoArt)

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose

(17th century rhyme against the enclosure of the commons in England)

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] began this series by drawing out some of the elements of the process of creating the common good, drawing on my engagement with four flagship projects of Valletta 2018. In passing, I have indicated some of the ways that some citizens are resisting the imposition of commercial imperatives on the Commons. Now I want to talk about my learning curve in relation to the formal process of resistance in Malta.

But first I want to go outside Valletta and back in time.

![]()

Soon after I returned to live in Malta some ten years ago, I attended a conference on best practice in equality held in a new hotel in what is now called Paceville. When I lived there almost seventy years ago, the area was St George’s Bay and Paceville was the British army officers’ quarters behind Dragonara Palace. We lived in St Rita St in the valley leading down to the bay. Our one-storey, rented house is now buried under hotels and bars.

I walk down toward the bay. I try to feel for the shape of the land under all that concrete.

Here is the fall of the valley running down to the beach. This concrete space must be the space where dad used to park his grey DKW motorcar. So to my right is the road where we used to race our go-carts. I feel again the hairpin down to the bay that now disappears in blocks of flats. To my left the steps go down St Rita Street. A small street sign hidden under the huge hot dog advertisement confirms it.

(Washing up in Malta, 2014, p72)

But is my sadness only about nostalgia and resistance to change?

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Who are we struggling against and what can we do individually as well as collectively to make a difference?[/beautifulquote]

For me, the coastline from Sliema to St George’s Bay represents the start and the continuing focus of the battle for control of public space and exploitation of the common good. Everyone I know complains about the onslaught of cranes, the gridlock of traffic, the overwhelming skyline of high-rise buildings. NGOs now organize our efforts to resist so that there are petitions to sign and public rallies to attend. Moviment Graffitti have been central to resistance to the ITS-db project that threatens to obliterate still more of St George’s Bay.

But who are we struggling against and what can we do individually as well as collectively to make a difference?

![]()

Here in Valletta, it has taken me many years to identify the networks of resistance.

Perhaps those networks had not been established when I first began to learn about the shared culture and spaces of this wonderful city. It seemed to me that it was taken for granted that government and commercial interests were in control of the common spaces and the common good of Valletta.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The Common Good of Valletta was perceived primarily as a benefit for visitors.[/beautifulquote]

I was reassured that Valletta’s listing as a World Heritage site would ensure that the skyline could not be altered in an abusive way and that the cars of non-residents were controlled by a permit system. In time, I came to understand that a third group of people also had precedence over residents in the common good of Valletta—visitors from outside the city from overseas and from other parts of Malta. In other words, the Common Good of Valletta was perceived primarily as a benefit for visitors. The fact that the residential streets were quiet after 8.00pm was proclaimed as evidence of abandonment rather than a pragmatic reality for people who had to get up for work in the morning.

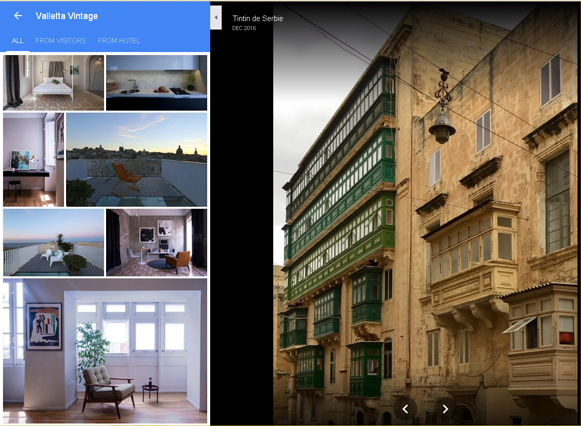

The gentrification of the city has gathered pace since then and continues. Resistance remains patchy and relies on individual efforts to keep up with the applications for planning permits that are affixed to every second door. Perhaps I will write more about that in coming articles. For now, I want to focus on City Lounge, a restaurant that overlooks and is part of the Common Good of St George Square.

![]()

More than two years ago, City Lounge added an aluminium and glass rooftop awning as well as a slightly recessed advertising sign without a planning permit. After a few months in operation and complaints from residents, City Lounge applied to the Planning Authority to sanction the structure.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]At the Review Tribunal, I was totally alone amongst a table full of suited men and was intimidated when I was called up to sit at the table.[/beautifulquote]

Several of us put in objections and the request for sanctioning was turned down. Residents heaved a sigh of relief and went about their daily lives expecting the awning to be dismantled. It wasn’t and City Lounge appealed, quietly enough that most people failed to pick up on the new development.

Somehow, I managed to notice, registered my continuing interest and turned up at the Review Tribunal. I was totally alone amongst a table full of suited men and was intimidated when I was called up to sit at the table. They explained to me in English that the lawyer had arrived early, submitted new plans and gone. They gave me the date for a second hearing. I was disheartened and posted my despair to a newly established, closed FB group called Valletta Residents Revival.

I owe my continuation with my objection to Dr Reuben Grima, another Valletta resident, who picked up on my distress and offered his assistance even though he himself had missed the opportunity of re-listing as an objector. Together we have kept track of deadlines to submit rebuttals, taken photos of the further abuse of the skyline with the addition of another advertising sign, and attended two more meetings where the lawyer for City Lounge has insisted that proceedings should be in Maltese because he wished to make complex legal arguments.

I respect the significance of Maltese language in shaping our shared world but although I am attending classes, my Maltese is limited to very basic interactions on the street. So things are becoming difficult for me. At the most recent meeting, the lawyer didn’t even show up and sent word to say he was abroad. To cut a long and continuing story short, the final decision will be made at a meeting in January that I won’t be able to attend because is my turn to be abroad. However, I am grateful to Reuben Grima who will attend in my stead.

Even though the odds appear to be stacked against us, I wanted to ensure that the awful process we were going through might at least sow a few seeds that could inform our response to continuing threats to our common good, so I’ll finish this article with the text of a statement that I read out and tabled at the last meeting of the Review Tribunal.

Unlike everyone else around this table, neither myself, nor my colleague are paid to be here.

We attend as concerned citizens who have no pecuniary interest in the outcome of the meeting. Our interest lies with the common good that we perceive to be under threat. In this instance, the common good refers to our heritage, the cityscape that we all share, the history that we read in the buildings and skyline as we walk around in the public spaces of Valletta. In this instance, the common good is under threat from the application by City Lounge to sanction their unpermitted construction of an awning and two advertising signs on the roof of a building that forms part of the common good of St George Square. For well over a year, City Lounge has abused our common good in order to increase their own commercial activity. Now, they seek sanctioning of that abuse by claiming that citizens have grown accustomed to the signs and to the permanent awning. They also appear to suggest that they have the right to make money off the back of the common good.

We all have busy lives and I certainly have difficulty keeping up with the catalogue of abuse of common good that is happening throughout Malta. However, citizens have not become used to the realization that one of our fellows is abusing the common good for their own enrichment. That is why I am here today and I am hoping that is also the purpose of this board.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]We have to examine the underlying system that assumes that people in power—whether politically or economically—have the right to use public space according to their own needs rather than as a shared resource for us all.[/beautifulquote]

We have yet to see if the growing chorus of voices seeking to strengthen the planning and enforcement system in Malta will have any impact. Some blame greed, corruption and collusion between government and business to enrich the few at the expense of the common good. Taking that position makes it difficult to identify possibilities for change. Strengthening enforcement may help in the short term but we have to examine the underlying system that assumes that people in power—whether politically or economically—have the right to use public space according to their own needs rather than as a shared resource for us all.

In my next article I return to the fourth of Valletta 2018’s flagship projects, The Valletta Design Cluster.

Read more:

Valletta and Our Common Good: Strada Stretta

Valletta and Our Common Good: is-Suq tal-Belt

Valletta and Our Common Good: MUZA

![]()

]]>

Sandro Debono talked about the significance of story in curating and of community engagement. I’m hopeful that MUŻA will enable a legacy of community engagement through pedestrian access that the University and Is-Suq alike have been unable to realize.

by Josephine Burden

Image by Raisa Galea (assisted by Fotor & GoArt)

The first and second chapters of the series are available here and here.

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]UŻA is the National Museum of Community Art and represents a physical move from South St to the Auberge d’Italie on Merchants St as well as a radical cultural shift from Fine Art to something else. At the closing event of Valletta 2018 on December 15 we were invited to visit and stroll around the ground floor which will continue as common access space.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]In relation to Valletta Commons, the move is significant because of the planned openness to the community by offering access from Jean de Valette Square through to Merchant St.[/beautifulquote]

The building is looking magnificent, the café is cosy and the restaurant offers fine dining. In relation to Valletta Commons, the move is significant because of the planned openness to the community by offering access from Jean de Valette Square through to Merchant St and by founding its curatorial practice in the stories of the community.

Here is a quote from my blog from the early days of the shift when I was beginning to notice how the walking routes around Valletta might link together through the common spaces of the buildings.

![]()

I was overjoyed when MUŻA unveiled their designs for their new venue in Auberge d’Italie. Sandro Debono, a guiding light for the shift, talked about the significance of story in curating and of community engagement. But my joy lay in the plan to enable a walking route through the courtyard of the museum from Jean de Valette Square to Merchant St. At last someone was giving consideration to the concept of the streets as the connecting life of the city.

Imagine the wonder of a stroll through City Gate, under the new Parliament House, past the back of St James Cavalier, across the back of Piazza Teatru Rjal, across Jean de Valette Square, into MUŻA for a coffee, across the courtyard and out on Merchant St, stroll the length of the street past the newly refurbished Is-Suq and the back of the Cathedral and Palace and then…

The flaneur arrives at a jumble of parked cars and motor-bikes cluttering the footpath.

So, imagine my joy when the University of Malta beautifully restored their Valletta campus and re-opened the connecting passage through from Merchant St to St Paul’s St. The space became a delightful linking haven away from traffic with occasional exhibitions to raise awareness of the University as a cultural institution engaging with the local community. The University became part of my cultural map and during the week, I walked through with my groceries and greeted the security people on the desk. Here was a cultural and academic institution that was part of the community and part of my life.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]My sadness is about a chance lost to create Valletta as a city were cultural institutions work with the local community.[/beautifulquote]

Until last week. I resolutely struggled through the bikes and cars and turned into the entrance to the University. The glass doors were closed and a sign demanded that I ring the bell for assistance. I did, and the door opened. I walked through into the calm space and smiled at the security person who had left her desk and was walking towards me.

“You will have to stop doing this,” she said, “You can’t just walk through with your shopping bags.”

I tried to counter my disbelief by talking about engaging with the Valletta community, about the value of a calm space away from traffic, about a campus that opened out to the community.

“But we are a prestigious institution,” she said, “There are plenty of other routes that you can use.”

And of course I will use them but my sadness is about an opportunity missed, a chance lost to create Valletta as a city were cultural institutions work with the local community to develop pedestrian routes that are safe and pleasant and build our social capital. Instead, the privileged world of the academic is separated from the everyday life of a working city. A pity.

![]()

So I’m hopeful that MUŻA will enable a legacy of community engagement through pedestrian access that the University and Is-Suq alike have been unable to realize.

However, an additional implication for Valletta Commons lies in the cultural shift from Fine Art to Community Art. At the closing event of the former site on South Street, people were invited to tell their stories and memories of the collection. I read a short piece from my third book, Middle Sea Dreaming, yet to be published. In this piece, I’m strolling around Valletta visiting some of the paintings, including the beheadings of St Catherine and of St John. My companions are Persephone and Minerva whose stories are told elsewhere in the book and I’ve just arrived at the Museum of Fine Arts.

I arrive at the Mattia Preti painting of the Martyrdom of St Catherine first. This painting is less compelling than the one in the chapel because this time the painter has turned the executioner away from the viewer and his sword is already drawn. He has received the instruction to proceed with the execution. I can have no influence on the outcome. Catherine continues to gaze upwards with her breasts exposed, dreaming of her rendez-vous with the lord of heaven. Will she find pomegranate seeds there?

I do not stay long before walking into the adjoining room where the walls are lined with horrific images of death. Persephone leaves me as I pass a man lying on the ground with his guts spilling out. Minerva stiffens her backbone. At the end wall, I find Judith and Holofernes.

Now, it is Judith who has become the executioner but she has the same workmanlike determination as the man who beheads St John in Caravaggio’s work in the Cathedral. She uses a sword rather than a dagger and one hand grasps the hair firmly ready to transfer the head to a bowl held by another woman. Holofernes lies on his back in the bed where Judith has seduced him. He has a look of surprise and horror on his face as he realises that his conquest of land and woman will not lead to the triumphant trumpet of Minerva.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Do women need to take on the same workmanlike violence as men to escape the oppression of the martyr?[/beautifulquote]

So do women need to take on the same workmanlike violence as men to escape the oppression of the martyr? Will that earn them the trumpet of Minerva?

Persephone rejoins me as I go out onto South Street and walk home along Strait Street. At the bottom end, before I turn right on St Christopher Street, I smile at the street art on an ancient door where someone has painted a confident woman sitting on a bar stool looking directly back at me. She has a long cigarette holder and invites Hades to sup with her. Persephone laughs. Perhaps I need to get out more.

![]()

The re-launch of the Museum of Fine Arts as MUŻA opens up another aspect of the Commons and that is the role of our shared culture in shaping the way we think. As long as we leave it to others to tell the stories, we abandon the Commons to the dominant voices. As a woman in old age, I am trying to shift that perspective in small ways. In my next article, I’ll discuss some strategies of resistance that I have tried to learn about since coming to live in Valletta.

Read more:

Valletta and Our Common Good: Strada Stretta

Valletta and Our Common Good: is-Suq tal-Belt

]]>

How does Is-Suq tal-Belt, the restored old market that covers a block linking Merchant St with St Paul’s St, shape up on good neighbourliness and enabling human interaction?

by Josephine Burden

Image by Raisa Galea (assisted by Fotor & GoArt)

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n my previous article about Strada Stretta, I identified two of the practices that enable the aim of helping citizens to live well in a city like Valletta that is changing rapidly. The first is good neighbourliness expressed through design and action that takes account of people. The second criterion assesses the extent to which public space—the streets, squares and parks—enables human interaction.

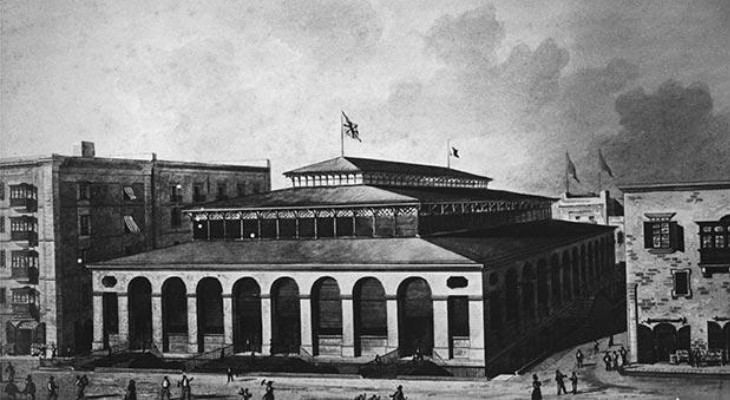

How does Is-Suq tal-Belt, the restored old market that covers a block linking Merchant St with St Paul’s St, shape up on these criteria?

The market opened with great fanfare at the start of the year. To achieve the restoration, the public/private enterprise evicted all the family businesses that still operated in the dilapidated site. Some of the butchers and delicatessen grasped the opportunity to re-establish themselves in garage shops elsewhere in Valletta. Others stopped operating. I miss being able to walk through the market from Merchant St to St Paul’s St and wave at my neighbour who ran one of the butcher’s shops.

Now, the pleasure of walking through a functioning market is prevented by the security needs of a supermarket. I never venture in. These days, I practice my Maltese in scattered garage shops, sometimes converted into shiny, new premises.

During the construction phase of Is-Suq last year, residents spoke out about the inconvenience of all night noise and traffic. Even before the opening, residents also objected, without success, to the large glass box that was added to the roofline on Merchant St, and to the large balcony that jutted out over St Paul’s St, narrowing the space available for pedestrians. The steps that had allowed pedestrian access through from Merchant St were replaced by a ramp under the cantilevered balcony supposedly for delivery trucks but never used for that purpose because it was too narrow.

Residents experienced partial success with the removal of the two large refrigerator trucks permanently blocking Felix St as well as the private property signs that appeared around the huge decks in front. When we challenged the placing of private property signs on the decks, the management declared that the signs were needed in response to young girls using the entry ramp for skate-boarding.

The battle to tame the enormous output of rubbish resulted in a clumsy gated enclosure that intrudes onto Felix Street at one end with a meshed enclosure that houses a huge gas cylinder at the other.

Cooking smells and the noise of air-conditioning vents permanently hang in the air. However, the pressure from residents protesting the inadequate design for the removal of rubbish did result in the government adding a cleaning station with industrial bins housed in cupboards at the end of the lane. Street sweeping equipment for the tourist areas of Valletta completed the obstacle course and straddled access to the pedestrian crossing along with delivery trucks avoiding the too narrow ramp.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The most recent lost battle was the further takeover of Merchant St with chairs and tables in the middle of the square.[/beautifulquote]

The most recent lost battle was the further takeover of Merchant St with chairs and tables in the middle of the square. At the Planning Authority meeting to decide on the proposal for further commercial activity in addition to a retractable awning over the already established front decks, the representatives of Is-Suq used their agreement with Valletta 2018 to justify their activities: Cultural activities would make up for the abuse of local residents.

So now, large banners with musical instruments have been hung on the façade and one of the food outlets has linked its promotional material with the Valletta 2018 production of Corto Maltese. Even the closing party of this year’s conference, Sharing the Legacy, was held in the upstairs area of Is-Suq and attracted police intervention as residents once again complained about the noise far into the night.

![]()

In terms of my criteria, Is-Suq fails. The new market does not demonstrate good neighbourliness and people have not been considered in design and action.

In addition, the restoration of Is-Suq tal-Belt has disrupted local traders in favour of a generic supermarket model, thus damaging the intangible heritage of daily domestic life. The management has tried to counter this by presenting a marketing image of traditional Maltese food but this is clearly for tourists rather than local residents. The functioning of the market has also impacted negatively on pedestrian routes and public squares including access to pedestrian crossings and a bus stop on St Paul’s St. The management has used the promise of cultural activity to justify this abuse.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]There is some positive legacy in that the new market has helped to galvanise residents into resistance.[/beautifulquote]

But there is some positive legacy in that the new market has helped to galvanise residents into resistance and some people do appreciate the predictable opening hours.

Tourists and Maltese visitors to Valletta, who do not have to find their way down the sides of the market to St Paul’s St, also appear happy to call into Is-Suq and I like to see non-paying visitors sitting casually on the benches around the decks where once Private Property signs were displayed. The addition of electric tuk-tuks to transport people from outside Valletta into the market has also provided work for one of my neighbours and is an excellent example for other businesses to follow. Pity that the vehicles are parked at the side of the decks so that again a pedestrian route is narrowed.

I have learned from Is-Suq tal-Belt that Valletta Commons, like commons elsewhere, are always contested.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]When one amongst us uses the commons such that the rest of us are disadvantaged, then our lives are diminished.[/beautifulquote]

As we share the commons, we constantly negotiate our relationship in terms of the good that we hold in common. When one amongst us uses the commons such that the rest of us are disadvantaged, then our lives are diminished. Now that the market has been permitted to establish an abusive relationship to the commons and our institutions celebrate the right of Is-Suq to continue operating, I am discouraged about the options open to us in seeking to rectify the injustice.

I boycott and I make a point of wending through Felix St every day just to make a point, but I think the opportunity for change has slipped beyond our grasp. That makes me sad but in my next articles I’ll track some more positive changes that have been happening.

Read the first chapter of the series “Valletta and Our Common Good: Strada Stretta” here.

]]>

After having been involved into the community consultation processes in preparation for Valletta’s bid to become European Capital of Culture, I’ve started to think about the things that we all share as humans—the commons or the common good.

by Josephine Burden

Picture by Raisa Galea

I hear the sounds of place more clearly as I grow old, as though the earth is calling me home. Some people stay and listen profoundly to one song until they fade into the walls and become the notes that others hear. Some move on and weave new harmonies into the song of life.

I wanted to hear the notes of new places and sail on a wash of sound until the rhythms carried me into deeper water where snatches of the songs of the world rippled across the surface. Perhaps I could pick up a minim here, a quaver there and although I can’t read music, I could work the notes together in my head and listen for the music in words.

Josephine Burden, Songs for a Blind Date, 2013, Prologue.

[dropcap]I [/dropcap] came to live in Valletta 8 years ago, just before the community consultation processes began in preparation for Valletta’s bid to become European Capital of Culture. As a resident and now a citizen, I have been involved with the community consultation in preparation of the ECoC bid, with annual conferences during the years of preparation, with research projects undertaken by Valletta 2018 partners, and with various creative projects as a participant myself. My own creative process has continued during that time and I like to think that the process of Valletta 2018 and my personal process have informed each other.

Two things have happened during that time: firstly I have begun to see my life as a process of action research; and secondly, I’ve started to think about the things that we all share as humans—the commons or the common good.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]I am hopeful that the concept of the commons will become clearer as I write this reflective series about Valletta and the changes that impact on us as residents.[/beautifulquote]

Action research seeks to understand process, generally with an aim that is shared amongst the participants. That aim is often about improving practice. My aim during the past ten years has been to learn to live well in a new country and in a new phase of my life post retirement from full-time paid work. I am hopeful that the concept of the commons will become clearer as I write this reflective series about Valletta and the changes that impact on us as residents.

First, let me say that many people of goodwill have worked hard to create enduring pieces of artwork and ephemeral spectacles around Valletta and Malta more broadly. The sheer volume of art exhibitions, new theatre productions, festas and fireworks has overwhelmed me.

There is no doubt that Valletta 2018 has raised crowding and noise levels in Valletta and I’m sure that there will be statistics that show this quantitative effect. Some people will call this the legacy of increased vibrancy and perhaps I am in a minority when I hope that increased noise and overcrowding will not be one of the continuing legacies of Valletta 2018. I raise the issue at the start of this series because I think that contradictions are inherent in the concept of legacy.

Some of those contradictions emerge strongly when I consider my experience of the four flagship infrastructural projects of Valletta 2018, and I’m going to start the series with one of them, Strada Stretta (Strait Street). Valletta 2018 claimed these flagship projects as significant in relation to legacy and they all involve restoration of historic buildings or sites. So how do they shape up in the light of the common good?

![]()

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The rash of commercial tables and chairs particularly around the junction with Old Theatre Street contradicts any legacy of public space as the lifeblood of citizen interaction.[/beautifulquote]

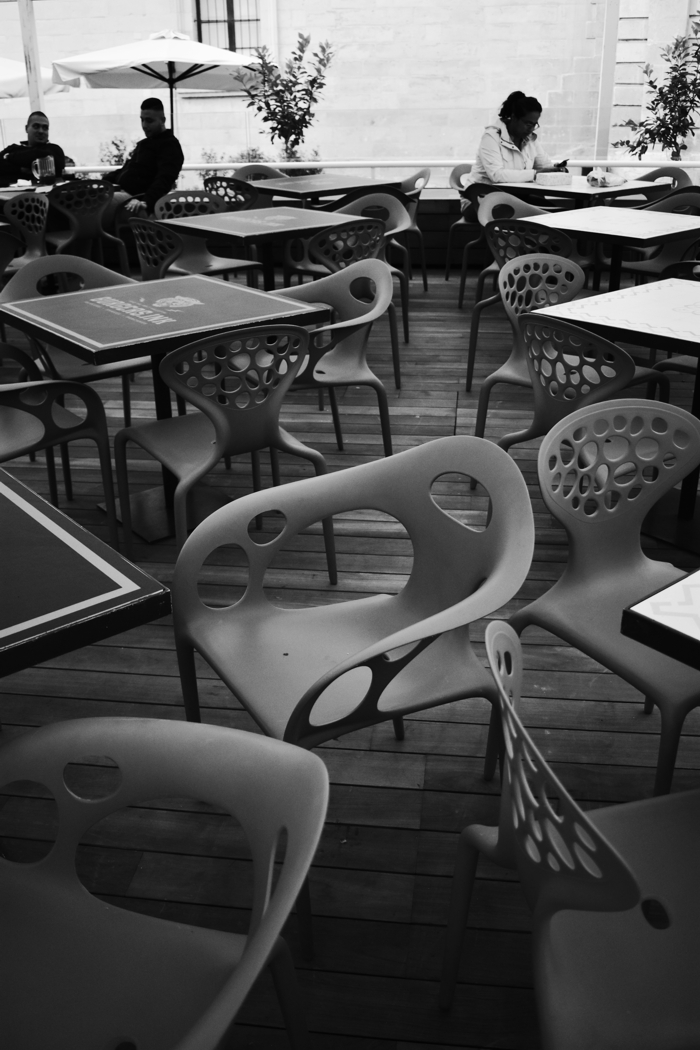

Strada Stretta was already a functioning street with residents living in assumed harmony with the run down cafes and bars that still operated along its narrow length. Some will remember the uproar that greeted the announcement that Valletta 2018 intended to turn Strait Street into another Paceville. That didn’t happen but the rash of commercial tables and chairs particularly around the junction with Old Theatre Street contradicts any legacy of public space as the lifeblood of citizen interaction.

Residents are prevented from accessing their front doors and pedestrians have to squeeze through insensitive party-goers. There are also a number of abusive structures in lower Strait Street that have justified their existence by claiming cultural partnership with Valletta 2018. These structures are said to be temporary and will be removed once the year is over. My hope is that Valletta 2018 will take some responsibility in making sure that the street wide balcony and cattle platforms for paying customers do not become an enduring legacy. I’ve already spent too much time battling with the Planning Authority as commercial interests apply to sanction unpermitted structures that abuse our common heritage.

However, Strada Stretta also now offers creative and social venues that support civil action and innovative projects. The Splendid Hotel has hosted multiple small performances and events that are innovative, challenging and contribute to a legacy of co-creation. The activist NGO, Moviment Graffitti, have their premises in a central spot on the street and host film nights and debates. Residents in the Vincenti Building in the upper levels of the street have begun to host their own events to raise particular issues in the public domain.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]However, Strada Stretta also now offers creative and social venues that support civil action and innovative projects.[/beautifulquote]

So the legacy of Strait Street is mixed and already, you are perhaps picking up two of the practices that enable the aim of helping citizens to live well. First, good neighbourliness and the extent to which design and action take account of people. And second, the extent to which public space—the streets, squares, parks—enables human interaction.

In the coming weeks, I will pursue these practices further in relation to three more of the flagship projects, Is-Suq Tal-Belt (the old Valletta markets), MUŻA (Malta’s national-community art museum) and Il-Biċċerija (Valletta Design Cluster).

]]>

“There are artists who are more into playing with the rules of art and artists who would rather play with the rules of society and the legal regulations. To me, the real art is the latter—the art that exists between creativity and criminality (not because it’s ‘criminal’, but because it challenges unjust legal practices).”

Image by Isles of the Left

Raisa Galea spoke with Pascal Gielen, Professor of Culture & Politics Sociology at the Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts, about the role of art and artists in reclaiming the contemporary cities from the commercial players. Prof. Gielen will be giving a talk at the Valletta 2018 Annual Conference on the 25th of October.

Raisa Galea: Your contribution is titled “Art, Politics and Public Life in the City of the 21st Century”. In what way do today’s relations between urban art and politics differ from those 50 years ago?

Pascal Gielen: Since the 19th century and until today, there have been four major shifts in the relations between politics, art and public life in the city. In the 19th century and until the end of the 1950s, arts in the cities were performed in a traditional ‘bourgeois’ way and were limited to fixed spaces, appointed for this purpose. For instance, statues were placed in specifically designated spots; performances happened in national monumental theatres. Arts were administered by national governments. That’s why I call urban culture with this kind of relationship the ‘Monumental’ city. Such a relation between art and politics was contested at the end of the 1950s with a symbolic culmination point in 1968.

The Paris protests of May 1968 provoked a monumental change. The demonstrations, reaching the highest point in the students’ protests, challenged the hierarchies—that, I believe, was the first significant shift from the traditional system of the 19th century. I refer to this shift in urban culture relations as the ‘Situationist’ city because the protests were inspired by the Situationists, who called for dismantling the rigid urban structure administered by highly hierarchical (cultural) institutions.

The second shift happened in the 1980s, when the students of the 1968 became in charge of the cities and the real estate. The protesters of the 1960s converted into the new management in the 1980s. At that point, cities were in permanent transformation, always under construction. And this was the time when politicians came up with an idea of city as a space for creative industries.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Once the politicians let the money flow freely around the globe, countries and cities had to find ways to attract new investment to compensate for the collapsed manufacturing of the industrial period.[/perfectpullquote]

Creative industry politics was born at the moment Tony Blair embraced Bono of U2. Third Way politicians, as we know, had a soft spot for the markets. Saskia Sassen, in her book “The Global City”, describes how cities turned into financial centres, the focal points of the global economy. Once the politicians let the money flow freely around the globe, countries and cities had to find ways to attract new investment to compensate for the collapsed manufacturing of the industrial period. And, as a marketing strategy, governments and local politicians came up with a plan of promoting creative industries. ‘Creative cities’ were meant to attract tourists. These ideas were also actively advertised by Richard Florida in his influential books “The Rise of the Creative Class” and, especially, “Who’s Your City?”.

The puzzling phenomena about the places reborn as ‘creative cities’ is that prior to the shift towards neoliberalism they were governed predominantly by socialists. A few years later—this is the third major shift—in a lot of cities the socialist and Third Way mayors were replaced by right wing conservatives and neonationalists, who adopted the idea of the ‘creative city’ for economic reasons, yet, at the same time, brought forward the ideology of, what I call, ‘repressive liberalism’ and even zero tolerance. This shift led to a higher police presence and a more intensive automated street surveillance. Such cities have a paradoxical relationship between art, public life and politics, which is why I call them ‘Creative-repressive’ cities. This is where we are at the moment.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The way creativity is defined, and in which places it is allowed to happen, determines society.[/perfectpullquote]

The way creativity is defined, and in which places it is allowed to happen, determines society. When creative activities are reserved for ‘creative’ fashionable districts (for instance, Vienna’s Museum District), then, inevitably, such spaces become restrictive. So, paradoxically, the artist can be free to create, but only in the creative district with its strict economic conditions.

I do not know what the future will bring. However, I do hope that the ‘Creative-repressive’ city will give way to the ‘Common city’, where social class distinctions will not be prominent and where creative communities—together with other people—will reclaim parts of the city from commercial interests.

Applying this classification of relations between politics and art to Valletta, I would say we are still at the stage two, where development of creative industries serves as a marketing strategy for the sake of attracting investment. The preparations to and the arrival of the European Capital of Culture 2018 have revamped Valletta—it is no longer a city of dilapidated buildings and an absent nightlife. There is, however, a concern that the city will end up as a theme park for entertaining tourists. What can be done at this stage to preserve spaces for public life in the city?

At this point, it is essential for the people of Valletta to keep control, collectively, over the key infrastructure, including culture infrastructure such as theatres, museums, and public spaces. By that I mean having a say on the programme of these theatres. The focus needs to be on reclaiming the city from AirBnB and other large real estate companies which extract profit from it. They milk the city dry, so to speak. These companies replace the use value of the city by a speculative exchange value, which is a disaster for the urban cultural and public life in the long run.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The real estate companies milk the city dry. They replace the use value of the city by a speculative exchange value, which is a disaster for the urban cultural and public life in the long run.[/perfectpullquote]

In theory, that would be an ideal scenario. However, Valletta is a city of contrasts and, in practical terms, that means deep segregation along the social class and partisan lines. The affluent residents of Valletta are predominantly in favour of boutique accommodations and AirBnBs, since that means more profit. The underprivileged population of Valletta lives in state-subsidised properties and is unlikely to march against AirBnB and commercialisation of space.

Unfortunately, Valletta is no exception. I see this happening in many other cities. To a large extent, this is a fault of the EU policies which stimulate competition between cities, incentivising them to develop unique features, but the cities end up copying each other in a bid to attract more tourists.

The situation in Leeuwarden—a Co-Capital of Culture 2018—is not too different. Having said that, from the beginning of the ECoC project, there have been active public discussions urging to invest into local co-operatives and green festivals that involve local farmers. Local people of Leeuwarden, too, had a say on which sectors should be invested into. We still need to evaluate whether these intentions have succeeded under a pressure from the international rat race between cities, stimulated by EU policy.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]With the current trajectory, Valletta will experience four-five more years of economic growth (with a severe gentrification process parallel to that), followed by collapse.[/perfectpullquote]

Going back to Valletta: with the current trajectory, there will be four-five more years of economic growth (with a severe gentrification process parallel to that), followed by collapse. In most cases, cities cannot keep attracting tourists indefinitely. Take Bilbao, for instance. There was a boom—a revival through the creative industries. In a few years’ time, the majority of avid travellers have seen the iconic buildings, the interest in the city dropped—and the boom was over. In such circumstances, cities have to come up with new spectacular projects—architectural and entertainment—for the sake of luring the tourists.

Which means that cities begin to function for a purpose of entertaining tourists…

And it also means that the same economic bubble is happening—albeit propelled by creative industries. In 5-10 years it will be over.

On a more optimistic note, how would cities that are currently at the ‘revival through creativity’ phase (or are at the ‘creative-repressive’ phase already) transform into common cities?

It is no historic fact, but an assumption. When collapse follows revival, cities fall into crisis, and in order to emerge again, they have to reinvent themselves—this is where the possibility for the positive change lies. The city of the future could be a Common city.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The movement for the Common city is driven by a heterogeneous group of people who are united by the common interest—reclaiming the city from the commercial, gentrifying forces.[/perfectpullquote]

Some shifts are already happening. The movement for the Common city is driven by a heterogeneous group of people, who, despite the professional and lifestyle differences, are exploited in the same way and thus become united by the common interest—reclaiming the city from the commercial, gentrifying forces. This struggle brings together activists, youth, social workers, factory workers, feminist and queer groups. Certainly, creative workers are drawn in too. In Zagreb, for instance, music bands and DJs, who squat places for the parties, join protests against large shopping malls and big companies moving into the district. These groups have a great potential; their protests are playful and provocative.

Other movements for the Common city are led by collectives like Recetas Urbanas—a Spanish architect collective whose members build houses and schools; who ask people what they would like to have built. Sometimes their creations are illegal or ’a-legal’, installed in spaces outside of legal regulations. In Sevilla, Recetas Urbanas created an insect-like structure, attached to the tree trunk, which also serves as a provisional shelter. As is in other cities, homelessness in Sevilla is on the rise, with homeless people being barred from public spaces. Tree trunks, where the provisional shelter by Recetas Urbanas is located, are not regulated by law, meaning that police do not have the legal means to evict a person from there.

The collective chooses such a-legal spaces for their intervention on purpose—to begin reclaiming the city for all, to open spaces up again and to attract attention to the problem. And not only that—they also built schools where people needed them and they continue assisting the local communities in a struggle to safeguarded cultural infrastructures from real estate speculation.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]To me, the real art exists between creativity and criminality (not because it’s ‘criminal’, but because it challenges unjust legal practices).[/perfectpullquote]

This is a completely different, radical way of doing art. The art for the Common city is art motivated by civil concerns. I do not call commodities designed for rich people ‘art’ anymore. That includes festivals, art displays and biennales—they exist within the art market and have their own distinctions, thus they are commodities nevertheless. There are artists who are more into playing with the rules of art and artists who would rather play with the rules of society and the legal regulations. To me, the real art is the latter—the art that exists between creativity and criminality (not because it’s ‘criminal’, but because it challenges unjust legal practices).

Somebody might say this is “instrumentalizing art for social causes”…

Yes, quite a few people say that and I disagree. These radical art collectives are autonomous in many more ways than artists creating for the market, for art festivals or biennales. Rather than adjusting to the demand of the market or the competitive professional art system, the collectives rely on public support, which allows them to focus on a broader variety of topics. Not all works of Recetas Urbanas are admired. Sometimes the public does not like their work, but the interventions are provocative enough to encourage further questioning.

The autonomy of Recetas Urbanas is fascinating. They get no support from the government (which government would support artists creating in a-legal spaces?), neither do they have private sponsors because the latter would not like to be associated with their explicit political actions. Yet, they have been going strong since 2003.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Not only do the radical art collectives operate within a democratic setting, but they also lay a foundation for the Common city’s infrastructure and the alternative economy.[/perfectpullquote]

And, naturally, the question is “where do they get the money?”. They collectively raise funds. They are skilled to reuse existing, discarded materials in new ways. They’ve built an extensive network all over Europe with whom they share the ideas and experiences. And they do it for free—peer to peer. Moreover, the works of Recetas Urbanas set a precedent: they inspire similar interventions in other places. Not only do the radical art collectives operate within a democratic setting, but they also lay a foundation for the Common city’s infrastructure and the alternative economy.

How is this kind of radical, socially motivated art different from community art?

In fact, it is quite different. Community art is driven by the notion of identity, it plays by conservative rules and is encouraged by conservative, nationalistic governments. It seeks to define “us” versus the other and, thus, exclusive. As described in our book ‘Community Art’, community artists are exploited by neoliberals and conservatives to compensate for the fruits of their policies—the disintegrating welfare state—by encouraging a particular kind of social cohesion, thriving on the ‘we’ feeling.

Unfortunately, I cannot think of any art collective similar to Recetas Urbanas in Malta at the moment. How can a society nurture such movements?

Certainly, you cannot tell artists to become activists or politically engaged. Such shifts happen when artists can no longer stay away from the consequences of the social, economic and political crisis. When cities turn into private commercial spaces that push people out, artists themselves become affected by it. They feel the urge to reinvent themselves and to organise their activity differently. And artists can inspire the radical change because they have a skill to make things visible.

Pascal Gielen is one of the keynote speakers at the Valletta 2018 annual international conference, Sharing the Legacy, taking place between the 24th and 26th October 2018. For more information, visit the conference’s website.

]]>

It is not the ‘ugly and stupid’ art that needs to be smashed and never sent for repair, but the insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

by Raisa Galea

Picture by the author

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ust as it happens with most topics in Malta—from over-development to fast food adverts—the disputes about the quality and the place of art in the society quickly become absorbed by customary narratives: partisan rivalry and the country’s purported status of the ‘citadel of mediocrity’. Despite their dull uniformity, these disputes are worth looking into—they could suggest how Maltese people tend to relate to each other and to the outer world.

To begin with, public access to the arts in Malta is limited: Only a few places such as Spazju Kreattiv at St. James Cavalier, Malta Society of Arts and MUZA (a project still in the making, previously known as National Museum of Fine Arts) welcome the general public—that is, the majority whose professional and consumption interests are not directly linked to the arts. Other than that, contemporary artworks are displayed at art events, of which there are plenty. Most frequently, art is showcased at private exhibitions and book launches which, by default, imply their secluded or commercial nature.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences.[/beautifulquote]

Engaging with the art at social events cannot be contemplative and serene due to the confines placed by an informal code of conduct that the attendees are expected to uphold. The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences. That turns events-going into a hollow performance aimed to affirm the social status of attendees which has little, if at all, to do with the art.

Artistic experiences in Malta are also profoundly shaped by the country’s minuscule size.