Climate change and the consequential natural disasters have become common drivers of migration—a phenomenon that will be further exacerbated as the climate crisis continues. Does the EU legislature address this issue?

by Maria Giovanna Manieri

Image by needpix.com

This article was originally published on our partner’s website, the Green European Journal.

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]ince at least 2015, the response to migration and increased arrivals of asylum seekers has become one of the most important—as well as most divisive—political issues in the European Union. The humanitarian urgency quickly transformed into a heated debate about perceived threats to identity and security, something exemplified by the inability of the European Council to agree on reform measures related to the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), and in particular to the reform of the Dublin Regulation. This establishes the criteria to determine which EU member state is responsible for examining an asylum application and would allow member states to respect the principle of solidary and responsibility sharing.

In the last legislature, the European Parliament was ready to negotiate with the Council on no fewer than seven pieces of legislation, with the aim to comprehensively reform the CEAS and specifically the Dublin Regulation. Member states, however, were unable to reach an agreement due to a lack of political will, and thus not a single measure to reform the CEAS was adopted.

While the overall EU asylum system is in dire need for reform, the much-needed legislative proposals allowing for more flexible legal channels for migrant workers and their families on the EU level have not yet become the focus of the co-legislators. And even though the actual numbers suggest that migration and the reception of asylum seekers in Europe could be managed in a much more effective and rational way, perceptions around migration are still impacted by the negative, fear-driven rhetoric promoted by the far-right.

Adding Climate to the Equation

Having seen how divisive the issue of migration has become in the political and legislative fora, it is not hard to predict that ongoing and future discussions around climate migration will not be an easy task for EU co-legislators. There is a widespread lack of recognition of climate change being one of the main drivers of forced displacement and reasons for migrants to leave their country of origin or residence.

“Climate refugees” or “climate change induced displacement” are the two common terms used to refer to this current challenge*. While definitions and terminology used to refer to the issue of climate migration are still debated, the phenomenon needs to find its normative framework to bridge the existing protection gaps, both in the European Union and internationally. The protection gap traces back in part to the fact that the term “climate refugee” does not exist in international law : the 1951 Geneva Convention defines a “refugee” as a person who has crossed an international border “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Climate migration is already a reality and is set to intensify further—even if, under current legal provisions, people who move because of a long-term, climate-related threat are considered voluntary or economic migrants with no entitlement to protection.[/perfectpullquote]

Climate migration, however, is already a reality and is set to intensify further—even if, under current legal provisions, people who move because of a long-term, climate-related threat are considered voluntary or economic migrants with no entitlement to protection. Even those moving after sudden environmental disasters only qualify for short-term humanitarian aid, and no longer-term support. If not closed, these legal gaps will cause major difficulties and humanitarian crises. The EU should therefore grasp the opportunity and act as a leading political force in this process.

An Issue of Poverty

It’s important to emphasise that climate migration is strongly cross-related to poverty. It is mainly poor countries that have the fewest resources to adapt to climate change, and climate change can, in turn, further aggravate poverty. Within these countries, it is the poorest populations that are forced to live in high-risk zones, such as riverbanks prone to erosion.

Most displaced persons (including those affected by climate change) migrate within their countries’ borders. National governments thus have a responsibility to manage migration and protect people who were forced to leave their homes, though they often lack the resources to do so. As a result, assisting those stakeholders through the established channels of development cooperation is essential for cushioning the negative impact of climate change.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It is mainly poor countries that have the fewest resources to adapt to climate change, and climate change can, in turn, further aggravate poverty. Within these countries, it is the poorest populations that are forced to live in high-risk zones, such as riverbanks prone to erosion.[/perfectpullquote]

On the other hand, development aid should not replace proper legal and institutional solutions to address climate migration, or serve as an excuse not to push for such solutions. This is why a coherent and binding solution—including appropriate definitions, rules, institutions and funding—must be determined at the EU and international levels.

In addition, the European Union should consider improving the flexibility of legal channels for labour migration for migrant workers and their families through an overall reform of the legal migration acquis in the EU. From a Green point of view, providing common channels for migration could complement our refugee policies by providing an additional path for people affected by climate change—especially when fleeing slow-onset changes of the environment, where the decision to migrate may be voluntary and planned, even if constrained.

The International Dimension

Due to the international nature of both climate change and migration, Europe is far from being the only territory impacted. Thus, there have already been examples of members of the international community coming together and defining strategies for cooperation on this issue. Most countries in the world, and also the majority of the EU member states have, for example, subscribed to two United Nations Global Compacts, frameworks for equitable responsibility-sharing between nations, which the EU is now starting to implement: one for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, and the other on Refugees.

Both of these documents could have a positive impact on the situation of climate refugees. On the one hand, the Global Compact on Refugees could allow for measures that lead to more effective protection for those fleeing their countries of origin. On the other hand, the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration identifies climate change as a driver of migration and suggests that countries work together to start planning for people who move due to natural disasters and climate change.

The Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration also restates the need to tackle the causes of climate change and to support adaptation in developing countries so that people are not forced to leave their homes. While recognising climate change as a driver of migration is an important first step, it is now crucial to closely follow the implementation of the Global Compact to ensure actual policy change, for instance by the establishment of humanitarian visas for those displaced by drought or rising seas.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]While recognising climate change as a driver of migration is an important first step, it is now crucial to closely follow the implementation of the Global Compact to ensure actual policy change, for instance by the establishment of humanitarian visas for those displaced by drought or rising seas.[/perfectpullquote]

The implementation, especially of the Global Compact on Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, is posing some challenges in terms of identifying next steps for both the EU as a whole and its member states. But there is absolutely no doubt that with the coordination of the United Nations (which established a Coordination Group for the implementation of the Global Compact) the European Union will have to engage concretely and actively with implementing the different objectives of the two Global Compacts.

Despite the optimistic signs, there are still reasons to be cautious. One of the most difficult tasks for the various signatories of the compacts is to refrain from picking and choosing on different objectives. The European Union and its members, for instance, should not emphasise their achievements in the fight against smuggling at the expense of other objectives. Instead, UN member states and the European Commission must put a greater emphasis on objectives that appear to be less cared for at this moment, such as saving lives.

It’s also crucial not to forget that the Global Compacts are not binding, and thus require further attention from political forces that want to make them relevant for European politics. One way is to introduce references to the Global Compact or its objectives in the EU’s ongoing legislative reforms. In this sense, despite the delicate new political balance of the European Parliament, the Greens may have an opportunity to be part of an influential majority to push for legislative initiatives and reform in the area of climate migration. But here, Greens in the European Parliament still need to determine how to find meaningful political compromises with a broad spectrum of political groups which should necessarily include the Socialists and Democrats (S&D), the liberal Renew Europe (RE) and the European United Left—Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) in order to find a majority. That remains an important task for the future.

Growing Interest, but Further Challenges

In the European Union, although the qualifications directive in place does not define climate refugees, some positive changes in attitudes can be observed. These are also reflected in resolutions (such as the European Parliament resolution of 12 April 2016 on the situation in the Mediterranean and the need for a holistic EU approach to migration) on which the Greens have voted in the near past.

Although the texts are non-binding and mentions of climate change as a driver of migration only appear as brief references, it still is an indicator that the issue is starting to be discussed. In October 2019 the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe called for protection measures to be developed in the asylum systems of Council member states to “protect people who are forced to move as a consequence of climate change.”

Whether these initiatives can turn into actual policy will depend, first and foremost, on how the executive branch of the EU is dealing with the issue. For now it is questionable whether the new European Commission under Ursula von der Leyen will be willing or able to come up with a migration and asylum policy that respects the proposal of the Council of Europe and provides a progressive solution to climate change-induced migration.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Efforts to discuss border procedures aimed first and foremost at providing short-term and short-sighted solutions will regrettably draw political and legislative attention away from the need to urgently develop long-term measures to introduce safe and legal channels to ensure proper and effective migration management.[/perfectpullquote]

The Commission’s attention is much more focused on border procedures that speed up the examination of asylum applications and then quickly return people to their country of origin, a country of transit, or a third country. It is to be expected, then, to see much political and legislative attention directed at making or establishing border procedures, emphasising the concept of “safe third countries” and pushing for assessment procedures that take place while asylum applicants are in detention.

Efforts to discuss border procedures aimed first and foremost at providing short-term and short-sighted solutions will regrettably draw political and legislative attention away from the need to urgently develop long-term measures to introduce safe and legal channels to ensure proper and effective migration management. In such a context, there is deplorably not much place for climate migration in the policy debate.

The Way Forward

In 2013, Greens in the European Parliament published a position paper on climate change-induced migration**. In that document, it was found that the Lisbon Treaty provides a broad enough mandate to revise the EU’s asylum and migration policy to include people who were forced to leave their homes due to the effects of climate change. The paper proposed possible solutions, such as circular migration schemes and preferential access for workers coming from regions seriously affected by climate change, and brought examples of some member states—Cyprus, Finland, Italy and Sweden—whose national legislation considers climate migration (at least on paper).

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Migration management solutions can provide a status for people who move in the context of climate change impacts, via for example humanitarian visas, temporary protection, authorisation to stay, and regional and bilateral free movement agreements.[/perfectpullquote]

Building on the experiences from the last years, it can be reiterated that regular migration pathways are able to provide relevant protection for climate migrants and to facilitate migration strategies in response to environmental factors. There are many migration management solutions available to respond to challenges posed by climate change, environmental degradation, and disasters in terms of international migratory movements. These solutions can provide a status for people who move in the context of climate change impacts, via for example humanitarian visas, temporary protection, authorisation to stay, and regional and bilateral free movement agreements.

A holistic and human rights-based approach to climate change could bridge several of the existing gaps simultaneously. Climate migration is a multi-faceted phenomenon. As such, linking policies on climate change, environment, development, migration, disaster risk reduction, conflict prevention and peacebuilding under a human-rights umbrella could therefore represent a major step towards improving climate change policy. Such a combination of efforts would provide a useful framework through which the international community could identify the most vulnerable people, and those areas where the need for action is greatest.

* The terminology has been subject to lengthy debate: terms like “environmental refugee” or “climate refugee” have been questioned, among others by the UNHCR, which emphasises that the term “refugee” already has a specific meaning in international law as defined by the Geneva Convention, and thus using it in contexts not covered by the Convention may undermine systems currently in place to protect refugees. The 2011 study Climate Refugees: Legal and Policy Responses to Environmentally Induced Migration prepared for the Civil Liberties Committee of the European Parliament suggests using the more general term “environmentally induced migration” to denote the broader phenomenon and “environmentally induced displacement” to denote forced forms of mobility primarily engendered by environmental change.

A number of politicians and experts, however, argue that “refugee” rather than “migrant” clarifies that movements are forced and not voluntary. Other experts suggest using the terms “environmentally displaced person” and “environmentally induced migration” because they see it as impossible to pinpoint the impact of climate change on a person’s decision to move. For others still, the word “environmental” is too broad: industrial accidents or nuclear catastrophe, for instance, are environmental but rarely related to climate change.

** Greens in the European Parliament are now collaborating with the Green European Foundation (GEF) to produce a new document aimed at renewing attention on the issue of environmental migration and pushing for practical solutions. For more on this project, visit the GEF website.

Maria Giovanna Manieri is the Political Advisor on Migration and Asylum for the Greens/EFA group in the European Parliament. She is a human rights lawyer, specialised in migrants’ rights and asylum. She previously worked as Programme Officer for the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM), where she has been responsible for developing the organisation’s legal strategies and work on borders and detention. She also represented PICUM before the Frontex Consultative Forum on Fundamental Rights and FRA Fundamental Rights Platform. Maria Giovanna also worked as human rights lawyer in the UK and in Spain and on the issue of internal forced displacement at the Italian embassy in Bogotá, Colombia. She studied law at the University of Bologna in Italy and at King’s College, University of London, and also holds a Master’s Degree in Diplomacy and International Relations from the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs Diplomatic School.

Strangers’ prying eyes frighten me now. After the horrendous murder of Lassana Cisse, I became, for the first time, worried about my husband’s safety. I fear for his life.

by Lara Bezzina

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]’m married to a black man. When he first came to Malta a few years ago, walking down the street together used to be simply a frustrating experience. Passersby looked at us as if we were two aliens from outer space. Their disapproving prying eyes followed us wherever we went. It angered me.

Depending on the day, I either stared back until the bystander looked away, or else muttered a passive-aggressive ‘good morning’, seemingly friendly but implying what-the-heck-are-you-looking-at?’ On one occasion, I am ashamed to say, I told that to an old woman who could not stop staring at us. I now realise that being so unnerved by this attention is pathetic. With time it got better, partially due to my husband insisting that I should not let gazes of others upset me so much. “Let them stare as much as they want,” he always tells me, “after all, what are they doing to us? Nothing!”

He could be right, but the intrusive gazes still affected me. So much so that it even affected my decision on where I wanted to live when we were looking to buy a flat. I couldn’t bear the thought of being the constant object of attention every time we left the house.

I had not always felt this way. Before my then-boyfriend visited Malta for the first time—from his evidently exotic African country—I was adamant that I would not make any excuses for the fact that my boyfriend is black. “No,” I thought, “we will act as normal.” Yet, acting ‘normal’ proved to be a tough task.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Before my then-boyfriend visited Malta for the first time—from his evidently exotic African country—I was adamant that I would not make any excuses for the fact that my boyfriend is black.[/perfectpullquote]

When I went to see a flat to rent, the first thing the landlady told me—before I had even entered the building—was: “Don’t worry, there are no Arabs or Blacks here”. I was so shocked. No, I was paralysed: while I knew this kind of racism existed, I never expected to hear this being stated in such a brazen way. I knew I should have walked away in protest, but I did not (so much for considering myself an activist).

Finding a decent place to rent on a strict budget was difficult—I was studying and my boyfriend was coming to Malta on a tourist visa, meaning he wouldn’t be able to work for the three months of his stay. Basically we were penniless—no excuse, I know, but the necessity of finding a roof over our heads won and I went in to see the flat, which I liked immediately. It was also within our budget.

Then came the true test: to tell or not to tell the landlady about my boyfriend’s skin colour. Again, I had always promised myself that I would never state my boyfriend is black. Why should I? Do others say their partner is white? But I did. “My boyfriend is black,” I told my landlady amid discussing the details, inquiring whether she had any issues with that. Cutting a long story short, we rented the flat with no problem, but I compromised my values in stating my partner’s skin colour. Yes, I swallowed a racist insult because we needed a place to stay.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Yes, I swallowed a racist insult because we needed a place to stay.[/perfectpullquote]

For two years we lived in Qawra, where we blended in the melting pot and rarely felt out of place. However, we recently moved to a different place we bought and, once again, we have to face gazes of other people—rather friendly, though inquiring. Recently, however, something has changed: not necessarily in people’s stares, but in my mind and in the way I perceive this attention. After the Ħal Far shooting that claimed the life of Lassana Cisse and injured two other African men, I no longer feel just frustrated at stares from strangers. Now I am tense.

Are those gazes mere acts of curiosity or are they imbued with hatred? Are they echoing ideological notions such as those expressed by the ex-Guardian of Future Generations? Am I welcome in Malta as the wife of a black man and the future mother of a black man’s child?

Strangers’ prying eyes frighten me now. After the horrendous murder, which shocked and saddened me, I became, for the first time, worried about my husband’s safety. I fear for his life: what if he’s shot while walking down the street? What if he’ll be murdered in cold blood while waiting for the bus?

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]After the horrendous murder, which shocked and saddened me, I became, for the first time, worried about my husband’s safety. I fear for his life.[/perfectpullquote]

Walking down the street with him, I keep wondering what people are thinking about us: Are they asking themselves “What the heck is she doing with a black man? Why are they here? Why doesn’t he go back to his country?” I always thought we were fortunate, living in our own bubble and surrounded by family and friends who accept us. But why would we be more fortunate than anyone else? After all, to many, we are just a freak couple: a white woman and a black man.

Of course, seeing the Mater Dei Hospital staff protest gave me some relief—not everyone thinks that way. Maybe there is still hope yet: maybe Malta will be warm and welcoming again?

Dr Lara Bezzina is an independent researcher, practitioner and activist working mainly in the fields of disability and development as well as broader social issues. She is also a visiting lecturer at the University of Malta.

]]>

The fact that deaths in the Mediterranean and the suffering of people migrating have been regular news items for years should not lead to a normalisation of this situation.

by Kathrin Schödel

Image by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]his is a short note to commemorate the anniversary of a horrendous event: on 18th April 2015, a boat having left from Libya with almost 900 people on board capsized in rough sea. Only 27 people survived, 850 people drowned. This catastrophe has a sad link to Malta: 24 corpses were recovered and taken to the Maltese Islands. Without being identified, they were buried in a communal unmarked grave in Addolorata Cemetery.

Inhabitants and visitors of Valletta can admire a precious marble knot close to the centre of political power in Malta commemorating a summit on migration held in the same year, in November 2015. Political leaders and “Malta’s geographic position which serves as a link between two continents” (inscription on the monument) are given valuable and prominent representation whereas the fact that the “link” between Europe and Africa manifests itself as a dangerous, even deadly, crossing for many, as a severing border rather than a linking knot, is not reflected.

When will those suffering the fatal consequences of current migration politics be remembered in a public space?

Unmarked graves, sea rescue being impeded rather than treated as a natural ethical responsibility, racially motivated attacks, even murder, the death of immigrant workers due to a lack of safety precautions—all such incidents contribute to a radical inequality in life and death. They also contribute to a dangerous, inhumane perspective on humans categorised as migrants brutally viewed as superfluous, dispensable. We must not be complacent about this development.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]When will those suffering the fatal consequences of current migration politics be remembered in a public space?[/perfectpullquote]

The fact that deaths in the Mediterranean and the suffering of people migrating have been regular news items for years should not lead to a normalisation of this situation. On the contrary, the regularity and seeming normality of these events is an ongoing scandal. It should serve as a strong reminder that there is no reason for being complacent, that European border politics, the politics of national economic competition are deadly.

In some reactions to the recent horrible murder of Lassana Cisse, perhaps a growing community of people in Malta, with and without a migrant background, uniting in shock and mourning can be observed. May this develop and grow towards a movement for equality and against discrimination and hatred towards people seen as ‘others’.

![]()

This short text is indebted to “Walk for Remembrance“; “Memorial for the shipwreck of the 18th April 2015”; “Event for Remembrance”, 2018– held in remembrance of the dead and demanding that all deaths—as all lives—should matter equally.

Kathrin Schödel lectures at the Department of German, University of Malta; her research interests are literature and politics, depictions of revolutions, constructions of gender roles, discourses of migration and utopian thought. She is a member of CAUR (Centre for Applied Utopian Research).

]]>

A poem by Hassan Yassin.

Collage by the IotL Magazine

I am a curse,

I am a deliberate curse,

Sliding down my secret chord attached to the uterus of the sky,

I hear the howls of the wind and wailing all about,

I talk to the flowers around me and I admire the songs of the walls,

These walls of my infinite isolation and my friend Fear,

Nothing provides me with a feeling of safety.

You who pass me by: do not ask me for Mercy in God’s sight,

Like a sinner calling to him for help,

Avoid seeing me,

Do not pity me.

Just give me a black bag so that I can put into it my defeat and my

contempt, and then I will chew it up and swallow it,

Give me a flame so that I may burn my waste,

I am a carcass bringing you unpleasant odours and Hate to your bodies

perfumed with flowers from Paris,

I cause you to feel Hate towards this dirty human who has undergone

all the terrors of wars.

I am a carcass where worms have found refuge,

I will not be last of their dreams and I will not be part of their

memories,

I do not know the date of my death,

Let me breathe deeply, close my eyes to open them again in the next

world,

Pray for my time to come soon,

The least glance at me only disgusts you,

Let me leave your world,

I have no existence here,

I am a stranger with no identity and no papers,

a heap of trash outside your doors.

I want to die and put my soul into God’s hands, I will finish as an angel

or a devil, what does it matter.

Let my death not be slow.

If only flowers grew on my heart, perfuming my lungs and painting

the worms that gnaw on me with multi-coloured designs, and the melancholy chimes

of the bells would cover the beating of my heart.

May your prayers envelop my fear.

Do not call this a body,

It is my rotting remains that observe you,

These remains that you despise.

Even those dogs look at me oddly, your well-dressed dogs who have

an identity and a name.

Oh most generous God, when will you look upon me with pity and

order my heart to stop, my heart filled with imprisoned flowers,

Its beating is killing me.

What can be worse than the word ‘refugee’ to name a man?

Filthy tatters cover my body and envelop it in warmth with a

pestilential stench.

Your pleasant smells disgust the lice who have taken refuge in my hair.

You, the passerby in front of me:

I am a migrant who has survived the fermentation of flesh in the Mediterranean

to come in the streets of Paris

These streets cleaned in the early morning, and I am here!!!

I am the lie of this world,

I am this share of publicised humanity,

They are looking for strategies to get rid of me, they spend colossal

amounts, they have created commissions to uproot me,

So I no longer know if I am piece of meat or a piece of asphalt.

This world shows me contempt,

As it does to my brothers sent back to be tortured,

Murdered in the name of international conventions,

Or those who have escaped from encampments, the cursed

fingerprints, and come from the African bloodbaths to find

themselves the lowest of the low,

But why???

Because I am a refugee, rotting through, lying down without even

being able to hope,

I am dying, anxious, in the silence of the fireflies, caressed by

multi-coloured butterflies.

Hassan Yassin is a Sudanese poet in exile.

![]()

This poem was originally published in French in the Magazine Littéraire in 2018 and in English in the catalogue of to be [defined], an artistic-anthropological exhibition, which forms part of RIMA project.

]]>

On May 25, 2018, the people of Ireland voted overwhelmingly in favour of repealing the 8th amendment of the Irish Constitution—the article that had hitherto made it effectively impossible to legislate for abortion even in the most extreme of circumstances.

by Beatrice White

Picture by William Murphy / Flickr (modified, some rights reserved)

This article was originally published on our partner’s website, the Green European Journal. It is also available in audio as part of the Green Wave podcast.

![]()

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he result was hailed by Leo Varadkar, the Taoiseach (prime minister), as a ‘quiet revolution’ but there was not much that was quiet about the outpouring of relief and elation that followed the official announcement of the repeal in Dublin Castle on May 26th. Although many expected it would pass, few predicted such a landslide. “We were confident of a win,” said Green Party Councillor Roderic O’Gorman reacting to the result, “but 66 per cent is shocking. I think we’re seeing a change in Irish society—an openness, an understanding that the old traditionalist, Catholic dogmas are being swept away—not before time, but I think it’s significant that it’s being done so publicly.”

Both the vote in favour and turnout (64 per cent) were even higher than for the 2015 referendum on marriage equality for same-sex couples. Donegal, the northernmost county of Ireland, was the only area with a ‘No’ vote overall. The highest ‘Yes’ vote was found in the capital (at 78 per cent for Dublin Bay South). The demographic shift in attitudes was highlighted by the fact that 87 per cent of 18-24 year-olds voted ‘Yes’. Turnout among women was much higher than at previous general elections, testifying to their high level of engagement with a mobilisation that was not only led but also driven by women across the country. Male participation, on the other hand, was lower, as some men viewed the question as a ‘women’s issue’ and chose to stay away.

The surprise with which the result was greeted shows the monumental shift in public attitudes and opinions in Ireland. This shift had been under-estimated by campaigners and policy-makers too, long reluctant to touch the issue of abortion, regarding it as too politically sensitive. As Minister for Health Simon Harris put it while the final votes were being counted, “the people led, and the politicians followed.”

Breaking the Silence

The 8th amendment of the Irish Constitution, equating the right to life of the ‘unborn’ with that of the mother, was introduced in 1983 following a referendum. Although abortion had been illegal in Ireland since the foundation of the state, the constitutional amendment was put forward in the wake of liberalisation of abortion regimes in Britain, the EU, and the US.

Rights organisations both within and outside of Ireland, backed by the UN, concluded that Ireland’s abortion laws were leading to serious human rights violations as the situation systematically discriminated against women and girls, interfered with their right to privacy and autonomy, as well as their right to medical treatment, and generally amounted to cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. “I think everyone agrees that the law as it stands is unfit for purpose and not satisfactory from any point of view,” said Seána Glennon, a member of lawyers for choice and solicitor from Longford. The women most affected by the restrictions are often the most vulnerable women, those “who can’t afford to travel or asylum seekers under Direct Provision who can’t leave the country to get an abortion, some of whom might have fled because they were raped,” she added.

“The 8th was part of the secrecy and hypocrisy that characterised this era,” explained former Supreme Court judge Catherine McGuinness at a public event in central Dublin a few days ahead of the vote, “There is less secrecy in Ireland today—since the facts about women traveling and taking abortion pills have to be accepted—but the hypocrisy is alive and flourishing, and takes the form of accepting but ignoring Irish women’s abortions.”

Since 1980, at least 170 000 Irish women have travelled to the UK for abortions and it is estimated that every day an average of three women take abortion pills ordered online, with no medical support or supervision at home. Taking these pills carries a 14-year jail sentence. Many in the medical profession are deeply ashamed of this situation, as it prevents them from being able to provide care or even proper information to patients. “These women are committing a crime, so of course they won’t go to their doctors,” said Veronica O’Keane of Doctors for Choice, speaking at a public meeting in Coolock at the end of April. “In Ireland we have been indulging in a psychotic fantasy that it isn’t happening, but it is happening—we need to wake up to reality and support women already having abortions.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Since 1980, at least 170 000 Irish women have travelled to the UK for abortions and it is estimated that every day an average of three women take abortion pills ordered online, with no medical support or supervision at home. Taking these pills carries a 14-year jail sentence.[/perfectpullquote]

Although campaigners had been active for decades, a number of high-profile cases contributed to putting repeal on the public agenda. The most notable was the case of Savita Halappanavar who died in October 2012 after being denied a termination, sparking outrage and calls for change. Vigils and protests were held, and the annual ‘marches for choice’ saw their numbers skyrocket.

In response, the government held a ‘Citizens assembly’ which brought together a representative sample of 100 citizens who were presented with facts, and listened to people from all sides of the debate. This process generated scepticism among those who saw it merely as a delaying tactic. However, in a crucial turn of events, the assembly came back with a series of far-reaching recommendations submitted at the end of June 2017, advocating a liberalisation of abortion laws that by far exceeded most expectations. A cross-party parliamentary committee was then appointed, which reviewed these recommendations and set out a legislative framework. In a somewhat scaled-back proposal, this involved access to abortion without restriction up until 12 weeks and afterwards only in limited circumstances, bringing Ireland in line with most other EU countries.

But despite its conservative nature, many still feared a tough fight ahead to win public approval for the proposal.

Building a Green Consensus

Ireland’s Green Party, Comhaontas Glas, along with almost all other political parties, called for a ‘Yes’ vote in the referendum and campaigned as part of a broad ‘Together for Yes’ coalition. Yet the party’s stance on the issue of choice has not always been so clear cut. “Among Greens it is a complex issue and there have always been people of different views,” explained Eamon Ryan, party leader and one of the two Green TDs (members of the Irish Parliament), “Like the country we came round in recent years, and wrote a new policy. It was contentious but in the end we had a very clear decision and our policy now very much mirrors what will be in the legislation.”

The party’s youth wing was instrumental in changing party policy. “Up until maybe three years ago, the Greens in Ireland had always taken a free vote on the issue of abortion and left it as a matter of conscience for individual members,” said O’Gorman. “But in the last few years, seeing the damage that the absolute ban on abortion was doing, with the death of Savita and so on, particularly our youth branch said it was time for the party to take a more active and clear stance on the issue. That was quite a significant change over the course of a few years and brought the party more in line with the policy of Greens across Europe.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Greens outside of Ireland also offered their support to the party. Caroline Lucas, co-leader of the Green Party of England and Wales, sent a message recalling the fact that if the status quo was maintained, it would still effectively be politicians in Westminster regulating abortion for Irish citizens, given the numbers of women travelling to the UK for terminations.[/perfectpullquote]

Greens outside of Ireland also offered their support to the party. Caroline Lucas, co-leader of the Green Party of England and Wales, sent a message recalling the fact that if the status quo was maintained, it would still effectively be politicians in Westminster regulating abortion for Irish citizens, given the numbers of women travelling to the UK for terminations. Although this solidarity was welcome, Greens in Ireland were cautious about any statements from abroad. “We didn’t want a sense of other people forcing their views on Ireland,” explains O’Gorman, “So it was good support but I think people realised that getting too involved risked being counter-productive.”

Campaigning in the ‘Post-Truth’ Era

Foreign interference and misinformation online were some of the main pitfalls that risked undermining the public debate around the referendum, particularly in light of the recent evidence of manipulation from abroad in other referendums and elections worldwide. This prompted Irish Times columnist Hugh Linehan to ask: “Is Ireland ready for its first post-truth referendum campaign?”

As the campaigning got underway, alarm bells began ringing about the level of campaigning from abroad on both sides and calls were made for assurances that this would be kept in check. In the wake of allegations of election interference through social media, Facebook announced it would block all foreign spending on advertising around the referendum in an effort to adhere to the country’s election spending laws (which prohibit donations from non-Irish bodies or citizens). A few days later, Google went one step further and banned all adverts relating to the Irish abortion referendum. The decision was hailed as historic by the ‘Yes’ side, although some still feared the bans could be bypassed through legal loopholes.

The strong Irish tradition of door-to-door canvassing may have helped undermine any such attempts. “That’s part of our democratic process,” explained Ryan, “What’s good about canvassing is that it is done in a respectful way that minimises the division that can sometimes come out of difficult, complex political issues.” For Ryan, canvassing was crucial to make sure the vote was based on a meaningful national conversation: “Getting people involved, having people knocking on doors, getting the debate happening, is a really healthy exercise. Even if it’s not the most decisive factor influencing vote overall, as many people may have already made up their minds, but by doing that you raise the quality and level of debate in general.”

The number of women who came forward to share their own personal stories during the campaign also proved decisive. Floods of powerful testimonials were published on social media, including devastating cases of women forced to travel for terminations of pregnancies even where a fatal foetal abnormality meant the baby would not survive after birth, because doctors were unable to act in Ireland if a heartbeat could still be detected.

Mary McDermott set up one such platform Everyday Stories—a website collecting stories from women about how they had been affected by the 8th amendment: “I think the likes of [everyday stories] can complement face-to-face conversations that people might be having with loved ones—and bring it back to the realities that real women have faced.” In response to criticism that this approach appealed to emotion rather than factual arguments, she said: “There is a factual side and an emotional one. We are human beings and it is an emotional decision. The other side are also free to tell their stories. It’s not about manipulating anyone but about opening up people’s eyes.”

The ‘No’ campaign used its own appeals to emotion, sometimes employing shorthand judged to be misleading or insensitive. These tactics included putting up posters showing foetuses—even in proximity to maternity hospitals—and claims that the proposal would legalise abortion up to six months and make Ireland the most liberal regime in Europe.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]A notable aspect of the ‘No’ side’s campaign was its ostensible secularism and absence of any overt appeals to religion to support their argument—in contrast to the 1983 referendum campaign. The contrast was a strong indication that the authority of the Catholic Church has significantly diminished in Irish public life in the wake of numerous scandals and cover-ups over the years.[/perfectpullquote]

Some campaign materials also featured disabled children and claims that conditions such as Down Syndrome had been all but eradicated in countries where abortion was available. These myths were repeatedly debunked and many felt the use of graphic imagery and false claims discredited the ‘No’ side in the eyes of voters. A notable aspect of the ‘No’ side’s campaign was its ostensible secularism and absence of any overt appeals to religion to support their argument—in contrast to the 1983 referendum campaign. The contrast was a strong indication that the authority of the Catholic Church has significantly diminished in Irish public life in the wake of numerous scandals and cover-ups over the years.

Bigger Than Ireland

Unlike many countries, Ireland does not allow its citizens living abroad to vote. Irish nationals lose eligibility after having been outside of the country for 18 months. Given the size of the Irish diaspora, this is perhaps not surprising, yet for many Irish emigrants this disenfranchisement deprives them of their right to have a say in the political development of a country to which they still feel deeply connected.

The ‘Home to vote’ movement, which began during the marriage equality referendum campaign, mobilised eligible Irish citizens abroad, and encouraged them to travel back to Ireland for the referendum. Those who had lost their vote contributed too, by founding ‘Repeal’ groups around the world to support the campaign, organise solidarity actions, and assist eligible voters making the journey home. Although the ‘No’ side also managed to mobilise some support outside Ireland, the great majority were on the ‘Yes’ side, leading some to warn that it could lead to a challenge from the ‘No’ campaign if there was evidence of a large number of ineligible voters returning to vote.

Ailbhe Finn, who has been campaigning from Brussels for years, said “Repeal Brussels was one of the first repeal global groups – there are now about 27, from Guatemala to Australia. It was hard to predict so many people would get behind it, but I’m so glad we were able to show that people still care about Ireland.” For those on the ground such as O’Gorman, it was “a very motivating factor and moral boost to see so many people making long journeys to come home.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]For the Greens and women’s rights campaigners, however, the work continues. “It’s not as if we’re in nirvana now,” Ryan pointed out, “how can you have free choice in pregnancy if you can’t get housing, for instance […] so there are other things we have to do.”[/perfectpullquote]

For the Greens and women’s rights campaigners, however, the work continues. “It’s not as if we’re in nirvana now,” Ryan pointed out, “how can you have free choice in pregnancy if you can’t get housing, for instance […] so there are other things we have to do.” Bolstered by its victory, campaigners from ‘Together for Yes’ are also looking ahead, and calls have already been made for change in Northern Ireland where abortion remains illegal. It is hoped that beyond the political reverberations of this historic result, the activists who made it possible—many of them young women not previously involved in politics—will channel their enthusiasm and energy into bringing about further progressive change in Ireland.

Having lived through two life-changing referendums in the space of three years, Finn is confident that further positive change is on the horizon. “First it came as a trickle, then a stream, then an unstoppable wave of change and progress in Ireland, and it’s not stopping here. Ireland needs to be fairer, more inclusive, to fix all the things that were broken, and this vote shows we have a majority to do that—that we are compassionate, progressive people. I think that with all of this power that we have now, we can move mountains.”

Beatrice White is the former Deputy Editor of the Green European Journal and worked on communications for the Green European Foundation. She has previously worked as a copy-editor for an English-language daily newspaper in Istanbul, Turkey.

]]>

The experience of migration is turned into a problem for those forced to or wishing to migrate—if they are seen and treated as ‘problematic’ migrants; for those who are welcomed as privileged expats, the story is different.

by Isles of the Left

Collage by Isles of the Left

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]igration has been a prominent topic in Malta for a long time. But what do we actually talk about when we talk about migration? Some of the articles published in Isles of the Left over the past year explore this question by asking who is referred to as a ‘migrant’, how ‘the migrant’ is defined and seen as the ‘other’ from ‘our’ perspective. Who can move from one country to another without being seen as this seemingly problematic figure?

These issues were also tackled by various cultural events in Malta this year, which we reviewed.

How about taking a perspective beyond the scandalising, often superficial and repetitive evocations of ‘crisis’, ‘flood’ and ‘flows’—dehumanising metaphors?

What are our reactions to the images reflecting the brutal realities of migration? How can we politicise our feelings of sympathy?

Delve into this reading list on Migration and Borders to encounter viewpoints beyond the mainstream assumption that migration itself is one of the central ‘problems’ of our time: a world which creates radical inequalities within and between countries, an economic system forcing us to be competitors rather than collaborators, deadly national border politics—these are central problems of our age.

The experience of migration is turned into a problem for those forced to or wishing to migrate—if they are seen and treated as ‘problematic’ migrants; for those who are welcomed as privileged expats, the story is different…

![]()

1. What Does it Mean to Be a Foreigner in Malta?

by Raisa Galea

Although they are uniformly referred to as “foreigners”, foreign nationals—global citizens, expats, migrants and refugees—do not receive equal treatment. In fact, they are treated accordingly to their status: where a wealthy expat is greeted with open arms, a migrant finds endless bureaucracy and a refugee—a barbed wire. Read more here.

2. ‘Deserving’ vs ‘Undeserving’: Refugees vs Economic Migrants

by Daiva Repečkaitė

Suffering seems to be an obligatory justification to enter Europe. In a fairer and more balanced system, economic migrants would have not had to take a perilous journey just to find work. But if trauma is the expectation, they get traumatised, too. Read more here.

3. Asylum Seekers: Burden, Cheap Labour or … Human Beings?

by Daiva Repečkaitė

The asylum applicants are met with two contradictory demands: to be traumatised and persecuted enough to be recognised as refugees, and to be physically and emotionally fit in order to contribute to the host country’s economy. Read more here.

![]()

4. To Be or To Be Defined?

by Francois Zammit & Raisa Galea

With a precision of scientific inquiry, the exhibition To Be [Defined] examined what it means—and feels like—to live as an antagonist in a story narrated by others. The mass and social media have been overwhelmed and oversaturated with the images of those who brave the perilous journey towards Europe and the West but the general public is rarely exposed to their own voices, and thus the human essence of these individuals. Read more here.

5. Matters out of Place

by Elise Billiard

What does it mean to be “in your place”? Perhaps, we can discern the fear of migrants by understanding how and why the society designates a specific place for each of us. In her book “Purity and Danger”, the British anthropologist Mary Douglas explains that every society promotes a particular order of things, in which everything has a definite place. It follows that each society has its own definition of dirt, but that the universal principle remains the same: “dirt is a matter out of place”. This is not only true for things, but also for actions, or even people.

Every day, the figure of a migrant is narrated as a “matter out of place”. This is their sole identity—the matter out of place, the filth that must be washed out. Read more here.

6. On How Not to Consider the Immigration Issue

by Michael Grech

The EU rhetoric heavily focuses on stopping smugglers from exploiting people and putting their lives at risk, instead of examining what induces them to seek the services of smugglers in the first place. Read more here.

![]()

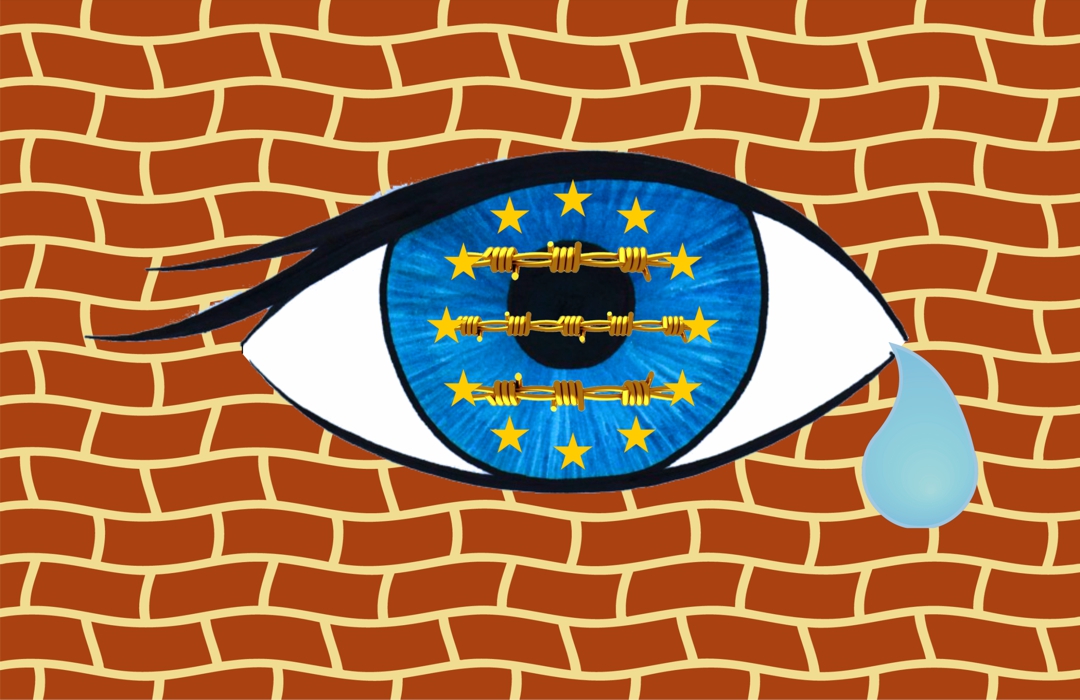

7. Building Walls: Fear and Securitization in the European Union

by European Alternatives

The far-right have manipulated public opinion to create irrational fears of refugees. This xenophobia sets up mental walls in people, who then demand physical walls. The report from Transnational Institute reveals that member states of the European Union and Schengen Area have constructed almost 1000 km of walls, the equivalent of more than six times the total length of the Berlin Wall. Read more here.

8. The Past, Present and Future of Free Movement in the EU

by Dawid Krawczyk & Anthony Valcke

The contemporary framework for the European Union was created in the 1950s, after World War II. The creators of the European Economic Community believed that if European countries were connected by strong economic ties, they would not get into military conflict with one another. In an attempt to strengthen those ties, the founders established the principle of the free movement of people, goods, services and livestock.

In theory, EU citizens are entitled to free movement around the entire community. What does this look like in practice? Read more here.

![]()

9. The Limits of Sympathy: Relating to Images of Distress

by Elise Billiard

The fear of witnessing the pain of others is caused by our empathy coupled with an intense feeling of powerlessness. And sympathy may even be a highly misleading path to trod on, if it does not encourage us to reflect on the reasons for horrors to occur. Read more here.

10. The Tragedy of Drowned Baby Dolls

by Anna Azzopardi

The reality of dead babies might be too much to swallow, and indifference to dead babies might strike a guilty chord or two. Thus, to free public conscience from sorrow and compassion for the dead children, a new story was injected in the media: The picture of the dead babies was staged. Read more here.

![]()

11. The Fate of Migrant Boats is the Fate of Europe

by Francois Zammit

The Maltese and Italian authorities used the law as a means of placing individuals outside of legal protection. The irregular migrants stranded on Aquarius are being subjected to the law but are not protected by it, thus effectively being placed in a zone of exception.

This kind of predicament and legal paradigm is what effectively allows for the creation of other zones of exception, namely refugee camps or asylum camps; this implies that Malta and Italy have effectively turned rescue vessels into a floating refugee camp. Whereas a refugee camp would normally be found on a specific territory, thus existing within the jurisdiction and responsibility of a specific nation-state, in this case the matter is even worse since there is no national law to protect the migrants on board. We are witnessing how the nation states are using their sovereignty and jurisdiction as a means of avoiding the responsibilities of international law. Read more here.

12. You Too Might Need Help of a Rescue Mission One Day

by Raisa Galea

The only issue of the rescue vessel and the only wrongdoing of the crew is saving lives—the lives that should be as valuable as ours, alas they seem not to be. There is always a possibility that Maltese, as any other people, might need to seek asylum. At the same time, the rise of the far-right parties to power in the EU countries makes the cancellation of visa-free travel within the Schengen all the more plausible. Read more here.

13. A Closer Look At The Rescue Vessel Berthed In Limbo

by Joanna Demarco

Sea rescue is not just about misery and suffering. There is space for hope and fun too. Toys, washing lines and origami birds in the engineer’s cabin are also part of a rescue vessel. Sea Watch 3 also serves as temporary home to its crew members. Read more here.

![]()

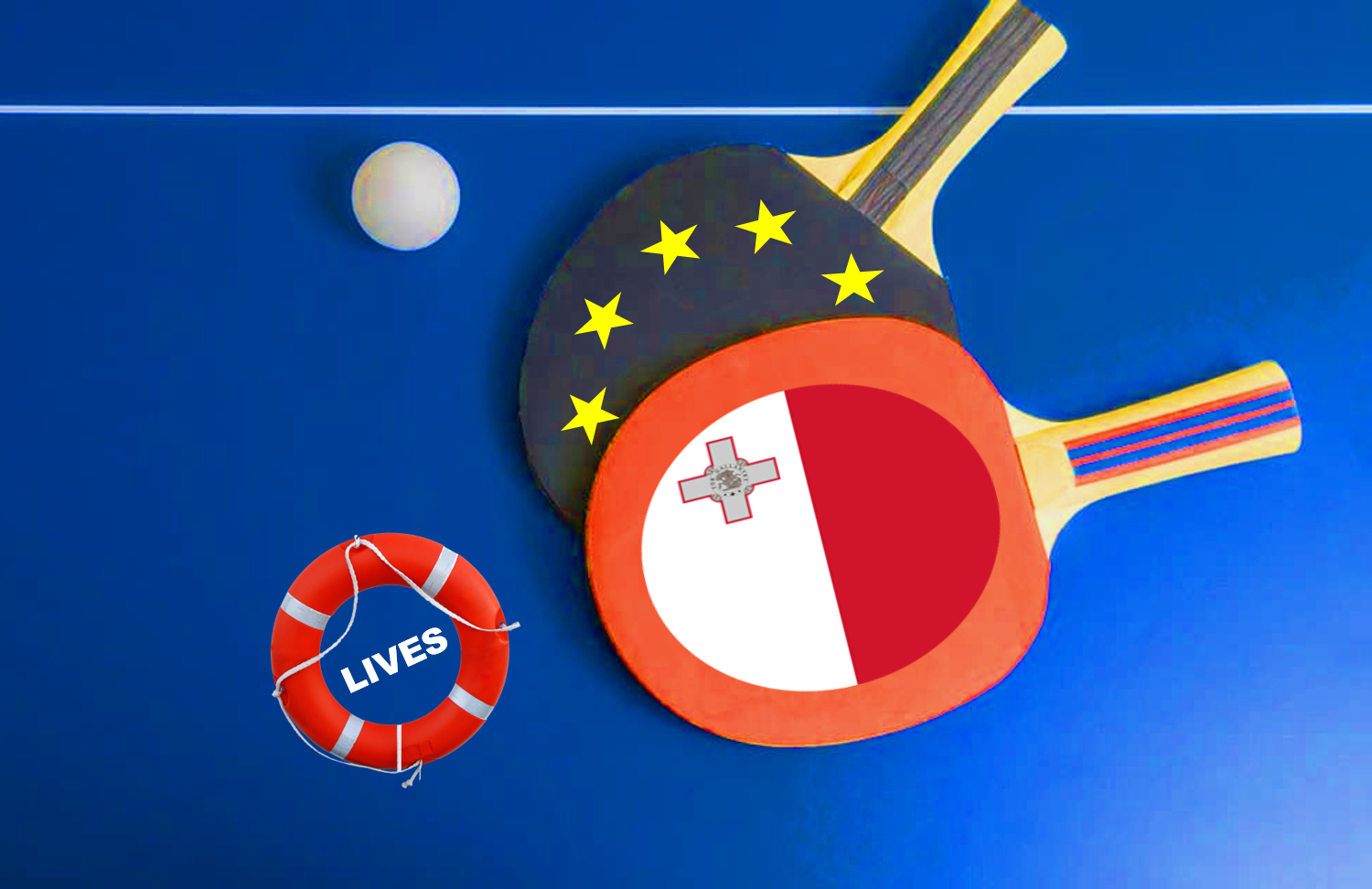

14. Regardless of Season, Playing Ping-Pong with People’s Lives is Unacceptable!

by Mina Tolu

When we wait to state something until things get really unacceptable, when we focus our arguments on the bad weather and on the Christmas season, we downplay the significance and severity of the actual issue—saving lives!—which then fades from the fore of public debates. Read more here.

15. Refugee Solidarity in Truly Challenging Circumstances

by Andrew Galea Debono

There are currently around 24.5 million refugees from different countries around the world. One of the major paradoxes of our time is the acceptance by economically developing countries to host hundreds of thousands of refugees, whilst much richer ones are more concerned with building barriers to keep those in need out. Read more here.

16. Spectres are Haunting Europe: A Film by Maria Kourkouta/Niki Giannari, Reviewed

by Kathrin Schödel

Like the proletariat which represents the structural scandal of the capitalist system, the systemic exploitation of the majority, the situation of refugees in the space inside the border, so to speak, stateless and powerless, reveals the very roots of suffering and suppression in this social world: the fact that the needs, wishes and interests of humans ultimately do not count.

If refugees and migrants do not simply “become like us”, forgetful of a system which will keep producing its outcasts, the ‘vanguard’ of refugees may become the sign of a new beginning, of the possibility of a different world. Read more here.

]]>

Suffering seems to be an obligatory justification to enter Europe. In a fairer and more balanced system, economic migrants would have not had to take a perilous journey just to find work. But if trauma is the expectation, they get traumatised, too.

by Daiva Repečkaitė

Collage by Isles of the Left

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]orty-four Bangladeshi nationals will be repatriated, the Prime Minister announced outlining the deal to share rescued individuals among several countries. After weeks at sea, with Italy and Malta refusing a safe port to NGO-run rescue ships Sea Watch 3 and Professor Albecht Penckt, 49 individuals from the most recent rescue mission, plus another 249 rescued previously have been sorted, literally and metaphorically.

We do not know yet how many among the others will be rejected and deported from the countries that agreed to process their applications, but the verdict for the 44 Bangladeshis is automatic, announced before the last ship disembarked. They are non-refugees.

Malta’s labour market has been voraciously drawing workers from India, Pakistan, the Philippines and elsewhere. And yet, 44 Bangladeshis who spent days at sea will be repatriated.

The number of destinations available for Bangladeshi migrants seems to be constantly shrinking. India has announced a crackdown on Bangladeshi migration. Gulf Countries are restricting migration and enacting preference regimes for their nationals. According to Migration Policy Institute, citizens of the country, still heavily dependent on remittances, cannot obtain visas or work permits without exploitative intermediaries.

To pay the fees, according to the International Organization for Migration, Bangladeshis resort to family savings or debt. Along the way, 98% spent at least a year in Libya and 63% told IOM that they had been held in a closed place against their will. It cost them between 1,000 and 2,000 USD to leave Libya by sea. Your T-shirt, most likely made in Bangladesh, has by far more freedom to travel the world than the workers who produced it.

Suffering as the Ultimate Justification of Entry

A refugee, in legal terms, is a person fleeing a well-founded fear of persecution. “In the first place, we don’t like to be called “refugees.” […] We did our best to prove to other people that we were just ordinary immigrants. We declared that we had departed of our own free will to countries of our choice, and we denied that our situation had anything to do with “so-called Jewish problems”,” philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote in “We refugees” in 1943.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]It is now the refugee status that makes a person who lacks a privileged background worthy of entering Fortress Europe.[/beautifulquote]

It is striking to observe how diametrically opposite the public discourse on refugee-ness is in Europe today—and how similar at the core it still is to Arendt’s time. Refugees are held in opposition to economic migrants, but in popular discourse, as well as in legal terms, it is now the refugee status that makes a person who lacks a privileged background worthy of entering Fortress Europe. Once they obtain this status, however, they are expected to be ‘productive’ and ‘contribute’ immediately, but that is a subject of another essay.

The popular credibility of asylum systems is judged depending on their capacity to sort applicants for asylum and send the non-refugees back to where they came from.

To counter the doubts regarding the share of ‘deserving’ ones among applicants, many sympathetic well-wishers broadcast the gory details of their journey to the general public. Suffering, as already outlined by Mina Tolu, becomes an obligatory justification to enter Europe. The sympathetic narratives that combine these contradictory expectations are understandable, but they solidify the worthiness imperative, and must be critically reassessed.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Asylum seekers owe their face, their story—and their trauma—to the general public in order to be pitied and accepted.[/beautifulquote]

During her talk at the University of Malta in 2017, anthropologist Barbara Sorgoni pointed out that personal openness and credibility have become implicit demands imposed on asylum seekers. Social workers and volunteers at some Italian reception centres expect them to generously share stories of their trauma. Some centres have made group therapy compulsory, withholding pocket money if asylum seekers do not cooperate, and wrongly creating an impression that credibility in social settings matters in the deliberation of their asylum case.

Looking at many sympathetic storytelling projects that have abounded since 2015, it is also easy to get the impression that asylum seekers owe their face, their story—and their trauma—to the general public in order to be pitied and accepted.

Economic Migrants Suffer, Too

Perhaps the crudest example is a published diary of Lithuanian photographer Vidmantas Balkūnas, who proudly admitted disrespecting the migrants’ right to refuse close-ups along the Balkan route: “I’m well aware that I’m at an advantage—I want to take a photo, and you want to get to Germany. If you raise your fist or make some fuss, you may have to forget the paradise of your dreams. So, covering themselves and grumbling like suspects in court, they reach the Croatian border.”

Hostile photographers aside, even well-intentioned volunteers, photographers, journalists, theater groups and others have hurried to harvest stories of trauma, adding to the hard emotional labour expected of asylum seekers.

But if trauma is the expectation, economic migrants get traumatised, too. With or without NGO rescue, the journey to Europe is so risky and perilous that it damages all migrants. There are exceptions in the laws, where deportation can be halted if a person is mentally or otherwise vulnerable, and it is rather surprising that the announcement was made about automatic deportation of the 44 Bangladeshis without making any vulnerability assessment. Their country does not pass the threat assessment by asylum authorities, but their individual journey from that country might.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]In a fairer and more balanced system, people would have not had to take a perilous journey just to find work.[/beautifulquote]

With increasing awareness of mental health and improved assessment, people should eventually be able to make their case and prove that after the dangers in Libya, abuse and weeks at sea, they deserve a respite and treatment of any health conditions they have developed. In a fairer and more balanced system, they would have not had to take this journey just to find work. Having realised how expensive and exhausting it is for everyone involved to have Balkan migrants try their chances at asylum, be housed, go through appeals and be deported, Germany has developed a work visa scheme.

In the absence of labour migration schemes, attempting asylum is currently the best bet for many residents of the poorest regions, especially in Africa, at becoming ‘guest-workers’.

While inter-governmental agreements and networks of employment agencies facilitate labour migration from countries like the Philippines, there are no comparable schemes for Africa. To access the system, one must first become vulnerable. So a perfectly healthy job-seeker from a relatively safe but poor country is abused and traumatised along the way, until he or she reaches the shores of Europe broken and exhausted. This does not make sense morally nor economically, but this is the logical result of a system that is geared at sorting ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ asylum-seekers and has few fair and accessible pathways to work.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Since there are no labour migration schemes for Africa, to access the system, one must first become vulnerable.[/beautifulquote]

Speaking at a forum in Alpbach in August, German Constitutional Court judge and legal scholar Susanne Baer argued for a post-categorical thinking in legal discourse. Our starting point should be a person who is seeking justice, she argued, and we can then look at the legal instruments and see what is available for that person—including social and economic rights, which are human rights as well.

Individuals come to Europe escaping political, social, legal and environmental injustice. This is a person persecuted for their activism. This is a person fleeing war. And this one is fleeing an environmental disaster. Are our systems robust enough to use this quest for justice as a starting point to build a fairer migration system?

]]>

When we focus our arguments on the bad weather and on the Christmas season, we downplay the significance and severity of the actual issue, which then fades from the fore of public debates.

by Mina Tolu

Collage by Isles of the Left

Day 14…

Day 15…

Day 16…

How long will this have to go on?

Thousands of people have raised their voices, calling on EU member states to allow disembarkation of the Sea-Watch 3 and Professor Albecht Penckt, two rescue vessels which over the last few weeks have been left at sea with 49 rescued refugees and migrants on board.

The Messages of Concerned Citizens

Various messages have been voiced in these past two weeks, from citizens, academics, politicians, NGOs, activists, and clergy. Those of us who call on the EU to allow these refugees into a safe harbour have used various messages.

To paraphrase the essence of a few of them:

On Saturday morning (15 days after the Sea-Watch 3 had rescued people from certain death out at sea), I posted an Instagram story complaining about the cold and calling for disembarkation to be allowed.

Just been woken up by a short hail storm in San Ġwann. Fuck. Imagine being out at sea in this weather. Feels like 2.0 degrees Celsius. NNW Force 7 winds. Still in bed. Warm enough. Comfy. And while I’m here full of regrets for leaving my proper winter clothes in Berlin… 49 refugees are still out at sea. EU member states abandoning their obligations and leaving 49 rescued people on rescue boats out at sea for 2 weeks! It’s time for EU states to step up their solidarity by a gazillion %. And allow people to disembark! Closing ports to rescue ships is not ok.”

The Focus Shifts Towards the Season and Weather Instead of the Core Issue

Most of us, including Alternattiva Demokratika (AD), only started speaking up when this specific case closed to the 10-day mark. Many who are raising their voices now might not do so in another case. This is the nature of current affairs—shift from one precarious headline to another—sensationalism at its full force! But what about the lives of people?

I’d like to analyse the timing and the messages that we share, and the potential impact of them.

When we wait to state something until things get really unacceptable—when we focus our arguments on the bad weather and on the Christmas season—we downplay the significance and severity of the actual issue, which then fades from the fore of public debates.

Indeed, Prime Minister Muscat himself said that it would be the easiest thing to play the part of the “Christmas saint”. He implied that this would set the wrong precedent which would turn Malta into the Mediterranean disembarkation centre—thus, the 49 people out at sea present Malta as a political victim (Fl-aqwa zmien).

But, we are not calling on Malta (or Italy or other EU member states) to be Christmas saints. We are asking the EU to save lives. We are asking the EU for solidarity.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The bad weather should not be the trigger behind care. Solidarity and equality should be the underlying values of our actions as a member state and as the European Union.[/beautifulquote]

Solidarity with those in need should transcend the festive season, despite the fact that in this instance it is Christmas which has a deep seated religious message telling us to care for those who are in some way persecuted and discriminated against. The bad weather should not be the trigger behind care. Solidarity and equality should be the underlying values of our actions as a member state and as the European Union—a union that is there for a reason beyond economy!

This is why I want to make it unequivocally clear: EU member states need to open their ports and allow the rescue ship to disembark, because they have legal, ethical and moral responsibilities to do so. Not because it is Christmas. Not because it is cold. Whether the rescue boat is out there for a couple of hours or a couple of weeks, whether it is summer or winter, disembarkation should still be happening! Let’s turn the ‘union’ part of the European Union into a reality.

Calling on the EU to Support Humanitarian Action!

The leaders of EU’s member states should not play political chess with people’s lives.

The Dutch and Germans have said that they would ‘welcome’ some of those rescued, if others do too. The Maltese won’t let anyone disembark—because it will set a precedent for future cases, and the Maltese state is very clearly about its intention to avoid such an action. Thus, the easiest ‘way out’ is to shift the responsibility onto the NGOs.

However, let’s be clear: the duty to care stays with the State not the NGOs. While shifting that onus of care, we blame the humanitarian NGOs. And every time these messages are spread, they become normalised: the public is tricked to believe that it is acceptable to put people’s lives in limbo while political talks and negotiations take place.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Outsourcing responsibility to other EU member states makes it acceptable for a sovereign EU member state to close its borders and shift blame unto another.[/beautifulquote]

Ultimately, outsourcing responsibility to other EU member states makes it acceptable for a sovereign EU member state to close its borders and shift blame unto another whenever a rescue ship saves people. But these are political fabrications for not wanting to shoulder responsibility.

Humanitarian NGOs should never be criminalised for saving lives. In a responsible, politically mature scenario, the EU would enable mechanisms to ensure safe channels for migration, so that saving people’s lives would no longer be needed. All EU member states should collaborate on a strategy for peace and integration. In 2018 alone—while there were ongoing negotiations at EU level—2,242 people died in the Mediterranean. How many of these lives could have been saved with the right system in place?

This case reminds us of the urgency to rehaul EU’s Dublin Regulation. In essence, the regulation determines that whichever EU member state a person arrives in first is the member state responsible to examine the application for asylum. This current system puts extreme pressure on EU member states at the borders of the EU like Malta, Italy and Greece to process the majority of applications for asylum. And it results in the closing of borders, ports, reactionary resurgence and dishonest political manoeuvring.

So we need to be looking at long-term solutions and seek to overhaul the Dublin Regulation on Migration. Until that happens, it seems clear that EU values and human rights will not be upheld. Let’s call on the EU to hurry up with their negotiations. People who are now abandoned out at sea should have been let in 2 weeks ago.

Mina Tolu is a trans, feminist, and green activist and an Alternattiva Demokratika – The Green Party’s candidate for the European Parliament. Mina has over 8 years of experience in local and international queer activism and organising, with a focus on communications and campaigns. Mina has also worked within broader feminist and green movements.

]]>

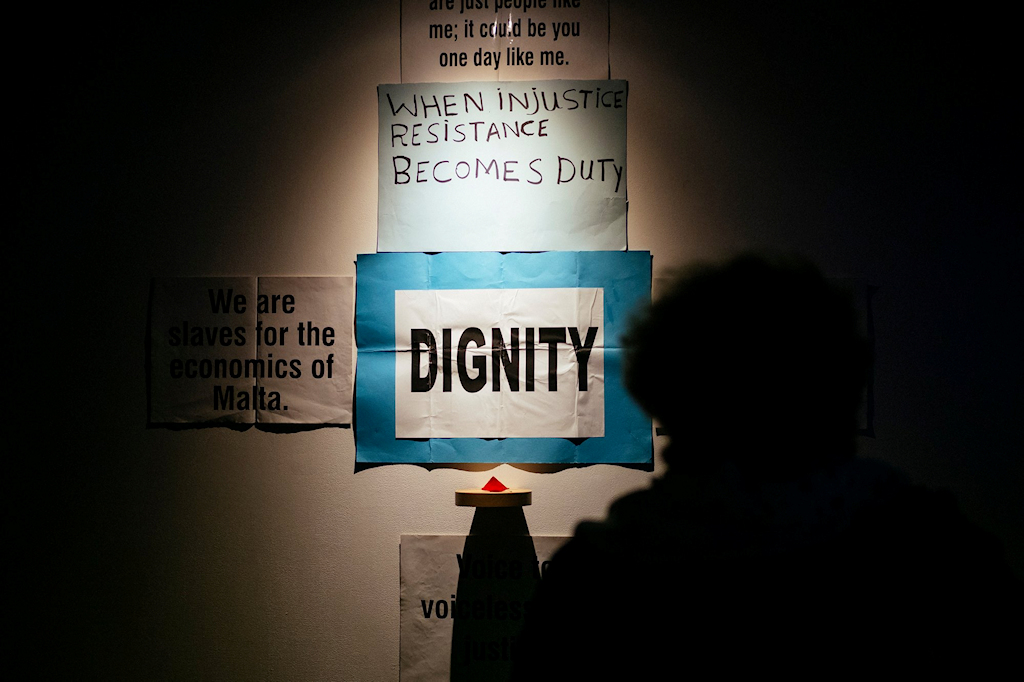

With a precision of scientific inquiry, the exhibition To Be [Defined] examines what it means—and feels like—to live as an antagonist in a story narrated by others.

by Francois Zammit and Raisa Galea

Picture by Alberto Favaro (adapted)

To Be [Defined] is not an ordinary art exhibition, if there is such a thing. It is not a fancy display of Instagrammable objects, neatly arranged at Spazju Kreattiv. The organisers—curator Virginia Monteforte, exhibition designer Kristina Borg, cultural advisor Alexandra Galitzine-Loumpet, project collaborator Sarah Mallia and strand coordinator Elise Billiard Pisani—defined it as ‘an artistic-anthropological exhibition dealing with past and contemporary displacement’.

Where does this description leave us?

Unlike the majority of conceptual and abstract artistic projects which tend to leave interpretations to the viewers, To Be [Defined] inscribes its message with a precision of scientific inquiry. By appealing to the aesthetic sensibilities of the viewers, the exhibition takes them on a tour de force journey through the experiences of exile which could only be interpreted in the context of grave institutional injustice.

The project does not seek to comfort the audience. The combination of hardship and beauty on display provokes outrage and begs for hope at the same time—both so vital to keep the spirit of solidarity and compassion alive in times of exclusion and apathy. The restriction of viewer’s interpretations is by no means a weakness of the project. By stating its message loud and clear, the exhibition still leaves a room for self-exploration. It poses four fundamental questions—Who are you? The one who defined? The one defined? The one to be defined?—which could lead to a surprising discovery of what it means to be who we are and who has the authority to shape our lives.

Who and What Defines Us?

Right upon stepping into the exhibition, the viewer enters a room split in half by a steel wire net. If one word could describe Do Not Cross by Alberto Favaro, it would be ‘precision’. The wire cuts through the desk in the center of the room, penetrates through the newspaper on the desk and passes through chairs. The net is light and, at first sight, does not seem to be a serious obstacle: the objects on the other side appear so within reach, albeit it is a deceiving impression. The borders, the work says, are for the people only. Bureaucracy, commodities, international sensations and data flows know no boundaries.

The Migration Objects Collective Project redefines everyday objects in the most inciting manner.

It is our memories, experiences and habits—not formal documents—that make us who we are both as a community and as an individual. Items like coffee makers, garments and other everyday paraphernalia are reimagined in a way that goes beyond their utilitarian and functional use. The ubiquitous espresso maker, found in every Italian household, is redefined as ‘a sense of home, memories, sharing’. The act of preparing coffee and the scent of the morning brew thus becomes a means of one’s memories and communal identity.

Within the same art piece there is a row of hanging clothes with a price tag attached to them. The tags, however, define a ‘human’ value and not the speculative market one. The scarf is ‘priced’ at ‘protection, warmth’—which, apart from being the practical purpose of the garment, also aptly describes the emotional dimension of the person wearing it. Just imagine the uplifting sensation that a warm woollen scarf can give to someone who is experiencing the freezing temperatures of a new land for the very first time?

In a similar poignant manner, sixteen miniature works in bronze by Katel Delia become historical artefacts; only Familja migAzzjoni–Legacy is not about a national or international history but a personal one.

In an equally touching and unsettling way these two exhibits invoke a familiar sensation we experience when looking at photos and personal items of our loved ones. In the object we recognise the person. And while observing the objects on display, we cannot escape the feeling of becoming acquainted with their owners and recognising our common humanity. Whereas the institutional discourse renders people as objects and numbers, the personal items preserve our individual identities. Living beings with memories and feelings cannot be reduced to statistics or administrative subjects, the project insists.

One of the most profound characteristics of the exhibition is that it does not draw a line between the experiences of Maltese and non-Maltese.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Maltese too were excluded from parts of Malta’s territory by the British colonial powers.[/beautifulquote]