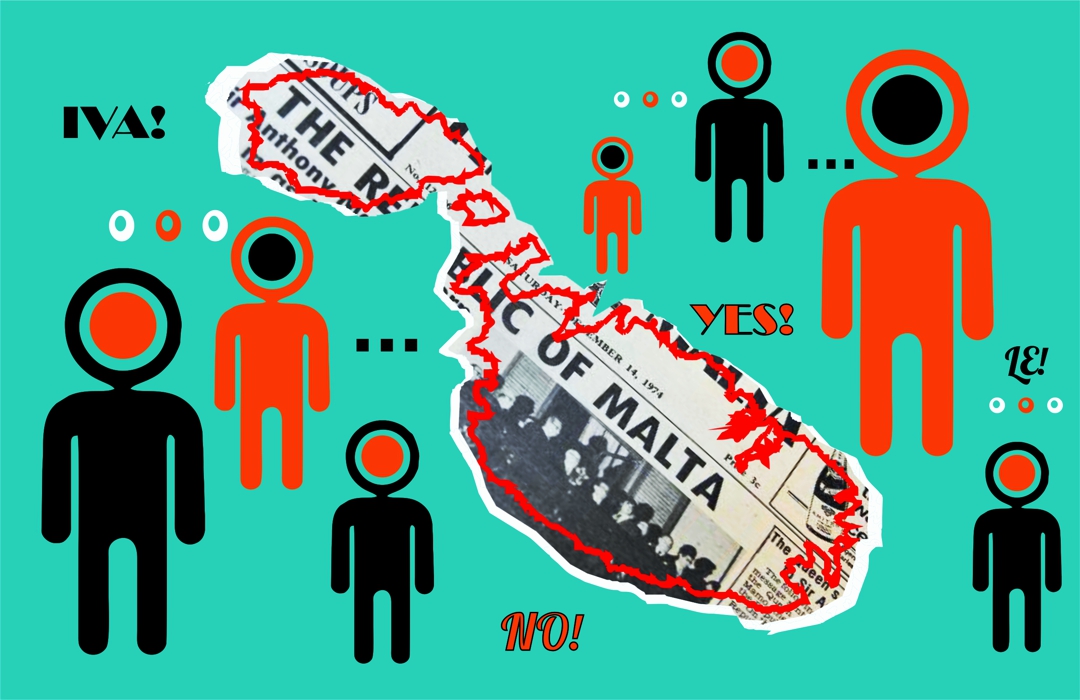

The dusk of ‘traditional’ hunting in MaIta is near, but the coalition of NGOs is not the one that will put an end to it.

by Raisa Galea and Francois Zammit

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he powerful influence of two interest groups—construction and hunting—has clearly shown itself once again during the current pandemic. Both have been permitted to carry on with their activities despite the quarantine measures to which other sectors were subjected.

A total of 6,148 hunters were eligible to hunt during the spring hunting season of 2020—a number that excludes 1,247 persons aged 65 or older. Meanwhile, busy and noisy construction sites particularly stood out against the backdrop of empty streets, and have made isolating at home too hard to bear for their neighbours.

Besides the apparent sources of their power—a sizable share in the national GDP in the case of the construction sector and a few thousand strong hunters’ lobby—there are other aspects to their influence. The exceptional dominance of the two lobbies, however, contains a curious paradox: as a vehicle of urbanisation, the construction sector should be the chief enemy of hunting, a so-called tradition performed in the countryside.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The exceptional dominance of the two lobbies contains a curious paradox: as a vehicle of urbanisation, the construction sector should be the chief enemy of hunting, a so-called tradition performed in the countryside.[/perfectpullquote]

In theory, the construction sector—the agent of ‘progress’ and modernisation in Malta—should be at odds with a guardian of ‘tradition’, as the hunting lobby positions itself. The two concepts—progress and tradition—are locked in inherent antagonism, since the former strives to erode the latter. However, in the Maltese political context, this antagonism is ambiguous and remains concealed.

To determine the reasons precluding construction and hunting from opposing each other as could be expected, we need to examine their relations to one another and the rest of Malta’s political actors.

Spring Hunting as a Symbol of National Sovereignty

Contemporary politics in Malta unfolds along two axes. On the one axis, it has been an ongoing trade-off between ‘progress’ and ‘tradition’. On the other, it’s defined by a rivalry between the country’s desire to demonstrate its European belonging versus preserving its supposed cultural authenticity.

For the past few decades, the young independent republic sought to establish itself as a modern European state—a path that led to joining the EU in 2004, while at the same time remaining under a tight grip of conservative lobbies, with the Catholic Church being the most powerful of them. Until 2011, Malta’s integration into the EU co-existed with the country’s legislation not permitting divorce. To this day, it remains the only member of the European Union with a total ban on abortion, which makes the country distinct and authentic in the eyes of the majority of its citizens—as a citadel of Catholicism that does not give up its values under secular pressure.

Spring hunting of birds, also clashing with EU regulations, remains among the most controversial and debated issues, unresolved by the 2015 referendum. Although not influenced by the Church and not a uniquely Maltese phenomenon, spring hunting has a similar significance in national politics: it is a bone of contention in the rivalry between perceived national uniqueness and questions about EU integration. To some, it exemplifies the country’s respect for local customs, while others see it as a national scourge and a failure to fully recognise the authority of the EU stance on conservation.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Spring hunting is a bone of contention in the rivalry between perceived national uniqueness and questions about EU integration.[/perfectpullquote]

As observed by anthropologists Brian Campbell and Diogo Veríssimo, the referendum transcended conservation-related matters. It was “an emotionally-charged moment where a ‘nation’ chose which values it wanted to be seen as having.” The pronounced goal of the anti-hunting lobby was to assert Malta’s keenness on doing away with such antics for the sake of complete EU-integration—a mission which, contrary to expectations, failed by 2,200 votes.

Recently, the Federation for Hunting & Conservation (FKNK) has appealed to the President of Malta, requesting that he suggest amendments to the Referenda Act. The petition, originally addressed to parliamentarians and signed by over 104,000 persons back in 2014, called for the safeguarding of a “legal, socio-cultural tradition”. Ironically, the hunters’ lobby chose to identify as a “minority” whose cultural practices must be secured from “capricious” reasons for calling an abrogative referendum.

Despite this strategic self-description, the FKNK is by far the largest NGO in the Maltese Islands with circa 10,000 adult paid-up members. It is therefore unsurprising that spring hunting enjoys the support of Maltese politicians, including MEPs.

Prior to the European Parliament elections in 2019, the majority of Malta’s MEP candidates, with the exception of Alternattiva Demokratika and Partit Demokratiku, promised to defend spring hunting at EU level if elected. Labour MEP Alex Agius Saliba—who was recently elected Vice-President of the Hunting Intergroup of the European Parliament—claimed that Malta will have a much stronger voice in the EU to protect the hobby “that forms an integral part of our culture and tradition.”

Political actors often justify their actions by referring to concepts presented as sacrosanct and fundamental. Among these justifications are national culture and identity, with tradition being their elementary building block.

Tradition is portrayed as something to be protected at all costs since it seems to have withstood the test of time and has supposedly existed for hundreds of years. Following this line of thought, a traditional way of life provides the necessary basis for being a member of the community and must be treated as a symbol of national identity and pride.

Examples of lobbying for ‘traditional’ practices abound. In Spain, bullfighting is defended as a tradition and the same applies to fox hunting in the UK. Bird hunting and trapping in Malta neatly fit into this category of ‘traditions’ to be safeguarded from extinction.

However, this form of reasoning is flawed.

Most of the time, so-called traditional practices are in themselves recent constructs that have been created in order to sustain a narrative of a shared national past. In the past, hunting of quail and grouse was not performed as a ‘tradition’ for its own sake. It was most commonly done for a practical reason: to obtain meat at a time when industrial farming did not exist. Also, since guns were not available back then, anyone keen on traditions should put away their hunting rifle and revert back to bow and arrow, or simple traps.

Rather than a commitment to preserving a supposedly unique way of life, upholding spring hunting is a cocky way of telling the EU to let Malta decide on its internal matters. Independent from the United Kingdom for a little longer than half a century, the country is still savouring its self-governance.

It is no coincidence that the two controversial national ‘traditions’—a total ban on abortion and spring hunting—were juxtaposed in a statement by President George Vella. “I cannot understand, how on a European level they take you to the European Court of Justice over the killing of turtle doves but then you’re frowned upon if you do not accept abortion.” The President thus implied inconsistency of the EU legislators and undermined the moral authority of the European Court of Justice, which criminalises the killing of protected migratory birds but not the ‘killing’ of embryos.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Spring hunting serves as a manifestation of national sovereignty and unwillingness to bow down to external power.[/perfectpullquote]

“Ewros fuckers”, as the anonymous hunter featuring in the most famous Maltese video ever eloquently put it, are not to tell the Maltese what to do in ‘their own’ country. In other words, spring hunting serves as a manifestation of national sovereignty and unwillingness to bow down to external power.

Construction as Progress

While FKNK lobbies for the preservation of a “Maltese traditional socio-cultural passion”, the construction and real estate sector have a contrasting mission—to advance progress and modernisation.

The Maltese word żvilupp stands for both ‘development’ and ‘progress’. In the eyes of many Maltese, hyper-modern tall buildings are associated with ‘progress’ and ‘modernity’. Following this line of thought, resisting the ongoing defacement of the countryside as well as of urban areas equals opposing progress and holding on to the past.

A few years ago, the narrative linking construction to progress took off with a blessing from none other than Malta Developers Association President Sandro Chetcuti: “Development can never stop, and if it does stop it means that the country has stagnated. Progress must continue as it is crucial for any country”, he said in an interview to The Malta Independent.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Progress must continue as it is crucial for any country”—Sandro Chetcuti[/perfectpullquote]

Advertising the new plans for a “six-star” mega-project at St George’s Bay, Corinthia chairman and founder Alfred Pisani urged his compatriots to “always accept progress.” Even the marketing of this project stood in opposition to anything traditional: the only other mega hotels classified as being six- or seven-star are those in the Gulf, mainly Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

Although heritage conservation activists decry highrise developments and the swift urbanisation of the countryside as distorting Malta’s authentic image, ‘safeguarding tradition’ is certainly not a priority when it comes to political decisions on urban planning and construction.

We can therefore conclude that an ambiguous compromise between embracing progress and preserving traditions has been reached on the basis of two criteria: profit-making and national pride. Respect for traditions is restricted to either profitable cases—for example, tourism-boosting colourful Catholic festivities—or practices that can be utilised for asserting national sovereignty, such as spring hunting.

On the other hand, upholding such ‘traditions’ may also function as an apparent compensation for the loss of natural and architectural heritage, sacrificed on the altar of economic ‘progress’. The effective role of ‘traditions’ that are compatible with the cause of profit-making is to signify stability.

Tradition and Progress in Malta: Allies, not Enemies

As a supreme guardian of conservative traditions in Malta, the Church does treat the construction industry as its antagonist: the Church’s Environment Commission warned about the “vain promises” of progress made by construction moguls.

Even if covertly, festa enthusiasts also do their bit in protecting open spaces serving as firework launching sites from over-building. Paradoxically, the hunting lobby has never openly voiced any concerns about the threat posed to its ‘tradition’ by the encroaching urbanisation and the swift disappearance of the countryside.

It would be logical to expect FKNK to be the most vociferous objector to proposed developments in the Outside Development Zone and the most ardent critic of architectural projects failing to comply with the ‘traditional’ image of Malta.

In theory, hunters, heritage conservationists and ENGOs have a common interest: preservation of rural spaces from development. Together, the hunters and the NGOs could have built a strategic unified opposition to the construction sector that is rapidly devouring these spaces. In practice, however, the situation is contrary to what could be expected: potential allies are mortal enemies.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]In theory, hunters, heritage conservationists and ENGOs have a common interest: preservation of rural spaces from development.[/perfectpullquote]

The Hunters’ Federation may have numerous reasons for complicity with over-building: its members, too, may be driven by contradictory urges and may be investing in development projects or work in the construction sector. However, there seems to be more than mere neutrality between the presumed antagonists—MDA and FKNK practically act like partners. What could possibly explain such bizarre power dynamics?

One of the most plausible explanations of this strategic conundrum is the presence of a common enemy—a broad coalition of NGOs and individuals, the majority of whom hail from an urban middle class background.

In the eyes of the hunters’ lobby, the threat to their rural way of life comes from a ‘progressive’ urban middle class whose delegates seek to align Malta with the European liberal democracies, thus ready to give up the country’s supposed sovereignty. In their 2015 referendum campaign, hunters fittingly instigated fear that other hobbies—fireworks and horse racing—will be next in line to be banned.

Antagonism between hunters and the urban middle class is mutual and deeply ideological. The ‘traditional’ Maltese folk and urban cosmopolitans espouse contrasting sociocultural values. According to one of the hunters’ spokespersons, the “extremist” anti-hunting campaigners are “often influenced by foreigners who come to our shores.” Regarded by the rural folk as agents of alien influence, environmental activists themselves detest hunters as a national scourge and personification of backwardness trapping the country “in Medieval times.”

The demand by FKNK for ‘public access’ to the nature reserves, currently administered by NGOs, simply verges on absurd since it goes against conservation. Again, the argument is clearly ideological and not about hunting per se: by making this request “on behalf of the Maltese people”, the Hunters’ Federation draws the line between ‘the people’ and the NGOs.

Thus, instead of mobilising against MDA’s detrimental effect to their interests, hunters shift the blame onto eco-activists who fight both lobbies simultaneously, on all fronts. The same coalition of NGOs opposing the construction lobby also clashes with hunters over the control of rural space and scolds firework enthusiasts (also potential allies for preservation of open space) over noise and air pollution.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Instead of mobilising against MDA’s detrimental effect to their interests, hunters shift the blame onto eco-activists who fight both lobbies simultaneously, on all fronts.[/perfectpullquote]

In other words, environmental NGOs and civil society groups are the conspicuous adversaries of—and are outnumbered by—the most powerful interest groups in Malta: the self-appointed guardians of ‘tradition’ and the self-proclaimed ambassadors of ‘progress’ alike. Having a common enemy turns intrinsic antagonists into allies and thus achieves the impossible by reconciling the opposites of construction and hunting.

‘Tradition’ vs ‘Progress’: What Will the Future Bring?

Given the special significance of ‘traditional’ spring hunting to Malta’s display of national sovereignty, it comes as no surprise that the government considers a stewardship agreement for hunters over lands at Miżieb and l-Aħrax tal-Mellieħa. However, in the long run, practicing this ‘tradition’ is likely to be reserved to such specifically dedicated areas only, as hunters are bound to be squeezed out of the countryside by the urban sprawl.

Evidently, there can be no hunting without the countryside. With or without future referenda on spring hunting, a continuation of over-building would eventually succeed in achieving what the 2015 referendum failed to do: eliminating this practice by simply taking over the space where it is performed—the remnants of the countryside.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Evidently, there can be no hunting without the countryside.[/perfectpullquote]

The hunters’ lobby does not seem to understand that tradition and economic leverage are hard to reconcile, and mistakenly regards the environmentally-minded middle class and ENGOs as its chief enemies. The dusk of hunting in MaIta is near, but the coalition of NGOs is not the one that will eventually put an end to it. The final blow will come from MDA.

In a concealed battle between the ‘tradition’ of hunting and the ‘progress’ of construction, the more economically significant latter is the likely winner. Unfortunately, this kind of ‘progress’ would be detrimental not only to the imagined ‘tradition’ of the hunting ‘minority’ but also to the majority of Maltese residents, not to mention the migratory birds. Public health and wellbeing would be compromised even further due to aggravated ecological degradation.

One day, a popular joke might become reality: construction cranes would replace all birds in Malta.

Isles of the Left forms part of Spazji Miftuħa—a coalition aiming to preserve access to public open spaces.

]]>

Upholding Malta’s abortion ban is a way of asserting national moral righteousness. But what kind of morality does this entail and what does it mean for women?

by Raisa Galea

Collage by the IotL Magazine

This article was originally published in Malta Today.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]part from Vatican City, Malta is the only country in Europe which criminalises abortion under any circumstances. The provisions within the Criminal Code of Malta have practically remained untouched since their enactment in 1854.

Yet, it is a fact that local women travel abroad to access abortion. As the law recognises induced miscarriage as a criminal offence punishable by up to three and four years of imprisonment—for a pregnant woman and a medical practitioner respectively—there are no official statistics on the number of women seeking the procedure abroad. The pro-choice coalition Voice For Choice-L-għażla Tagħha estimates it at around 300 a year. Although this number is significantly below the European average (183 abortions per 1000 live births, as reported by WHO Europe), even a possibly underestimated figure indicates that women in Malta are no exception and undergo the procedure despite the blanket ban.

Celebrated by pro-life groups and challenged by the pro-choice lobby, the special status of Malta in relation to abortion is acknowledged by both sides of the divide. And just as was the case with the divorce and spring hunting referenda, the abortion debate transcends the limits of a practical, if controversial, matter, and enters the domain of identity politics and ideology.

Since the ban does not prevent hundreds of abortions per annum from taking place elsewhere, the major goal of lobbying in favour of the current legislation is to keep abortion away from Malta in particular. In a nutshell, a key argument against the decriminalisation of abortion is to preserve Maltese national identity as rooted in conservative politics, Catholic morality and family values.

Family Values and Superior National Morality

Anyone following the debate is familiar with the dualistic narrative.

While the pro-choice perspective argues in favour of recognising a woman’s right to bodily autonomy and to ending an unwanted pregnancy, the pro-life camp insists that life begins at conception and equates terminating a pregrancy with murder. The pro-choice campaign is treated with much hostility by various segments of the Maltese population. Activists are verbally assaulted; their arguments—dismissed.

Delving into the reasons for such vehement opposition to abortion in Malta, anthropologist Rachael Scicluna suggested that in societies where family ties are strong and conservative views on gender roles prevail, the concept of embryo is intrinsically linked to the concept of family. Thus, at a subconscious level, abortion could be perceived as a threat to the very foundations of Maltese kin society and, consequently, objecting to its introduction is a way of defending family values and the status quo. While this hypothesis offers an insight into the pro-lifers’ social insecurities, there seems to be another narrative fueling hostility to abortion: a fear of outsiders’ intentions to dismantle core Maltese values.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]There seems to be a specific narrative that is fueling hostility to abortion: a fear of outsiders’ intentions to dismantle core Maltese values. [/perfectpullquote]

In response to my request for a comment on the cases of Maltese women accessing abortion abroad, Malta Unborn Child Platform refuted the estimate: “We know, for example that around 55 women of Maltese nationality undergo abortion in the UK, but we do not know how many of those women travel from Malta or actually reside in the UK. There may be also foreign women, residing in Malta, who go for an abortion in the UK.” Bluntly put, the organisation implies that having an abortion is incompatible with being a Maltese woman living in Malta.

A conspiracy of a sinister foreign plan to force abortions upon the Maltese is making the rounds in some people’s heads and on social media. This is evident in personal attacks hurled at the prominent feminists Andrea Dibben and Lara Dimitrijevic, both of whom are Maltese albeit with foreign-sounding surnames. “Go do Satan’s work in your own country!!!” and “go back home and kill your babies” are common responses to their pledges. This conspiracy is also propagated by Gift of Life Malta: according to the organisation, having “political allies within and outside of Malta” is part of the pro-choice camp’s strategy.

Asserting that a woman must not be forced to gestate against her will stirs mass outrage. Female pro-choice activists are advised to watch over their own sexuality and assume responsibility for the pregnancy, even if it resulted from rape. One of the comments to the LovinMalta article that reported such verbal abuse read “How many rapes [do] we have in Malta? Very rare / Even so a woman that got raped is always free to go abroad to kill the unwanted baby in case she got pregnant from rape.” Although this argument is based on a poorly informed perception of the infrequency of rape in Malta—sexual assault often goes unreported due to a victim-blaming stigma—it nevertheless demonstrates that it is possible to oppose decriminalisation of abortion in Malta and condone ‘murder’, as long as it happens elsewhere.

Another proof of the abortion ban being perceived as part of a national identity in need of protecting comes from the church. By stating that “our work in favour of life at all stages underlines our identity as Maltese”, Auxiliary Bishop Joseph Galea Curmi implied that the country’s devotion to Catholic faith is rivaled by the Vatican alone—the only other state in Europe which criminalises abortion.

President George Vella, too, spoke in favour of the current legislation at a recent event organised by the Malta Unborn Child Platform. His presence at the manifestation clearly signalled state support for the anti-choice cause—a national mission that is “on the right side of history.”

Furthermore, the President expressed doubt about the moral authority of the European Court of Justice where “you’re frowned upon if you do not accept abortion.” Considering that Malta’s political crisis and high-profile corruption remain a subject of international scrutiny, Vella’s statement is indeed politically loaded. Outsiders—immoral ‘baby-killers’—are in no position to criticise the only remaining bastion of Christian values in Europe. In other words, upholding Malta’s abortion ban is a way of asserting national moral superiority.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Outsiders—immoral ‘baby-killers’—are in no position to criticise the only remaining bastion of Christian values in Europe.[/perfectpullquote]

And it could be the authorities’ effective means of diminishing international criticism, undermining verdicts of the European Court of Human Rights, and by extension—possibly brushing off the demands of constitutional reforms altogether.

Between ‘Progress’ and ‘Tradition’

As Aleksandar Dimitrijevic, director of Men against Violence, pointedly observed, the official demands to reform laws against abortion by the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner receive little support from the rule of law advocates in Malta. Civil society groups, striving to bring Maltese legislation in line with the rest of ‘normal’ European countries, usually so attentive to international assessment, turn a deaf ear to the calls for abolishing the abortion ban. What could be the reason for such a selective commitment to human rights as defined by international legal bodies?

Contemporary politics in Malta has been a trade-off between ‘progress’ and ‘tradition’. For the past few decades, the young independent republic sought to establish itself as a modern European state while, at the same time, remaining under the tight grip of the Catholic church. An ambiguous compromise between embracing progress and preserving traditions has been reached on the basis of two criteria: profit-making and national pride.

‘Progress’ came in a financially lucrative form: free market economics, construction boom, luxury megadevelopments, and ‘blockchain island’ fantasies. Corinthia chairman and founder Alfred Pisani pompously encouraged his compatriots to “always accept progress”—unless, it seems, this progress is unprofitable and undermines the authority of the church, the guardian of conservative traditions. A progressive stance on reproductive rights, thus, barely enjoys a fraction of the state’s enthusiasm for ‘progressive’ elite property developments.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]A progressive stance on reproductive rights barely enjoys a fraction of the state’s enthusiasm for ‘progressive’ elite property developments.[/perfectpullquote]

What about Malta’s LGBTIQ legislation? Some may argue that by becoming the first country in Europe to ban gay conversion therapy in 2016—and by legalising same-sex marriage a year later—the Maltese state has declared its committment to progressive social policy. Seen from a different perspective, however, this was rather a win for national pride. The reform gave even conservative locals a reason to savor the international recognition and be proud of Malta leaping ahead of the curve in something, compared to the rest of Europe.

In the case of abortion, it is precisely the blanket ban that makes Malta ‘special’ in the eyes of its citizens—thus, distinct from other formally secular European states. Defending the country’s role as a citadel of superior morality, besieged by ‘baby-killers’, could be a seductively heroic narrative. Also, the abortion ban as an untouchable ‘tradition’ may function as an apparent compensation for the loss of natural and architectural heritage, sacrificed on the altar of economic ‘progress’.

Institutionalised Stigmatisation of Women

“Does our President consider his citizens who have had an abortion murderers?” Voice For Choice-L-għażla Tagħha asked in response to George Vella’s pro-life endorsement. This is certainly one of the most pertinent questions of the debate. Another question: if abortion is murder, why does the punishment for induced miscarriage range from eighteen months to three and four years of imprisonment? Isn’t this too mild a punishment for murderers?

As noted by former Labour deputy mayor Desirée Attard in her doctoral thesis, the Criminal Code itself implies that “a woman’s life is more valuable than that of the foetus.” As per Article 242, the punishment for performing an abortion that results in the death of the woman is that of life imprisonment. This disparity in punishment—four years versus a life sentence—“means that the law recognises that a foetus is not a person”, unlike a woman.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]If abortion is murder, why does the punishment for induced miscarriage range from eighteen months to three and four years of imprisonment? Isn’t this too mild a punishment for murderers?[/perfectpullquote]

Thus, if the legislators did not equate abortion with wilful homicide in 1854, what makes this an acceptable argument in 2020? Such contradictions further reveal the deeply ideological basis of the pro-life argument, whose goal is to preserve the conservative status quo by denying women an established human right and exerting control over their bodies.

Apart from being legally incorrect, equating abortion with murder means regarding women who have undergone the procedure as murderers. This is no less than a means of institutional oppression and ostracisation of women. Both the endorsement of the anti-choice perspective by the President and the common perception that links it to Maltese identity and national morality celebrate Malta as a conservative patriarchal state.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]With a blessing of both the state and society, the ‘pro-life’ camp turns fellow women citizens into outcasts who must suffer in silence.[/perfectpullquote]

Society and the state force Maltese women into shame for accessing a healthcare service available to women in the absolute majority of countries worldwide. Such marginalisation, reinforced stigma and cultivation of guilt are detrimental to women’s psychological and social wellbeing; they cause loss of self-esteem and induce fear of abandonment. With a blessing of both the state and society, the ‘pro-life’ camp turns fellow women citizens into outcasts who must suffer in silence.

Is stigmatising compatriots a sound basis for moral righteousness?

]]>

In spite of the unprecedented political crisis, Joseph Muscat remained what a tattoo on his right bicep purportedly states: Invictus. He resigned on his own terms—bizarre outcome, considering the severity of the allegations implicating him in the Caruana Galizia murder cover up. We cannot fully comprehend it without finding out what sustained his baffling popularity.

by Raisa Galea

Collage by the IotL Magazine

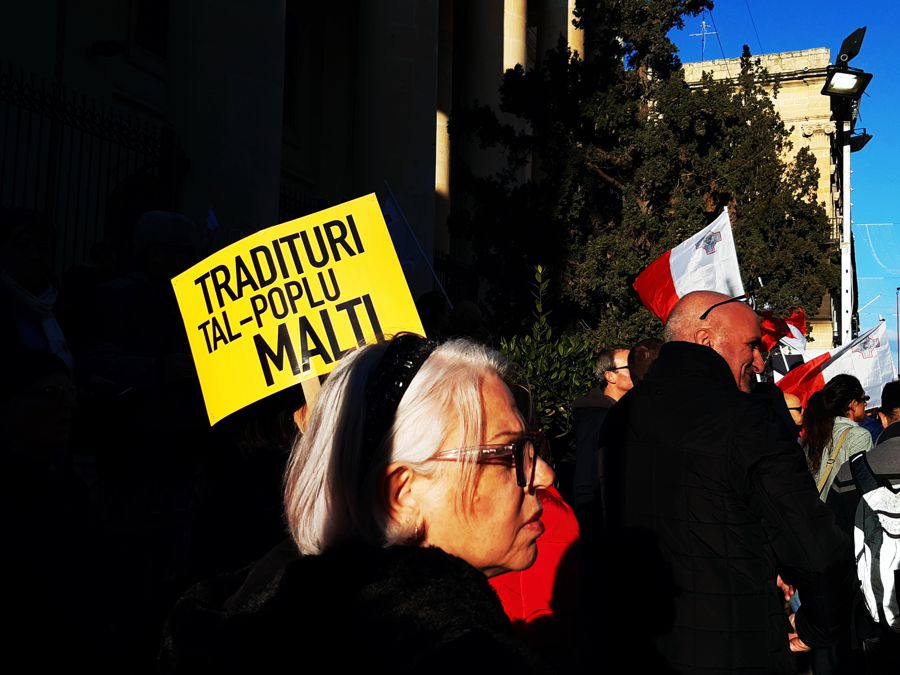

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]or better or for worse, the legacy of the last six weeks of 2019 will certainly become imprinted in our collective memory: amid a continuous stream of appalling revelations, the once-unshakeable authority of Joseph Muscat’s administration began to crumble like a house of cards. Or so it seemed. For a brief moment, the former prime minister was on the brink of an abyss, never before so close to falling from grace. Yet, despite the demands for his immediate resignation chanted by thousands of protesters in Valletta and the pressure of the European community, he left his seat of power on a high note—on his own terms.

In spite of the unprecedented political crisis, Joseph Muscat remained what a tattoo on his right bicep purportedly states: Invictus. Considering the severity of the allegations implicating him—the middleman’s testimonies claimed involvement of his former chief of staff Keith Schembri and “Kenneth from Castille” in the murder plot—this outcome is beyond bizarre.

The Daphne Caruana Galizia murder trial has set a decisive precedent: for the very first time, accomplices in a political murder have been identified and brought to justice. The shocking extent of impunity was laid bare for all to see. We learned that the murderers planned the crime in cold blood, expecting to get away with it (“Aren’t these like the Maltese police? Don’t worry” Fenech notoriously told Theuma in response to the latter’s concerns over the FBI getting on board). They fully relied on the inaction of their loyal appointees, convinced of their influence over police investigations and the judiciary as a guarantee against prosecution.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The Daphne Caruana Galizia murder trial has set a decisive precedent: for the very first time, accomplices in a political murder have been identified and brought to justice.[/perfectpullquote]

The murder trial is also a pivotal test for democracy in Malta. At its very core, this is a probe into whether or not members of the ruling elite can get away with crime. On the one hand, charges against Yorgen Fenech, a mighty tycoon, undermined the idea that the powerful stand above the law—a dent to impunity that can’t be overlooked. However, this landmark development was incomplete. The fact that the prime minister did not resign immediately under public pressure sent a different message: grave abuses of power can go on as long as the majority allows it.

According to a survey conducted by MaltaToday in December, the majority (58%* of respondents) were either content with Joseph Muscat’s delayed resignation or believed he should have carried on. Only a small fraction (2.8%**) of PL voters thought that the prime minister who was later named as ‘2019 man of the year in organised crime and corruption’ must step down immediately. We cannot fully comprehend this outcome without finding out what sustained his baffling popularity.

A Battle for National Pride and Identity

At its essence, Maltese politics revolves around the topic of national identity. Looking back at the most memorable debates of the past few years, we can note that all of them—from the economy, the Great Siege monument strife and LGBTIQ rights to spring hunting, Valletta2018 jablo sculptures and even Benna rebranding—were framed from the standpoint of national identity. Practically every subject debated in Malta is a quest for national pride. Even the European Parliament elections were characterized by the slogans “Malta f’Qalbna” and “Flimkien għal Pajjiżna”, despite the fact that Maltese patriotism is nowhere on the EP’s agenda.

Every development in this post-colonial island state seems to be a reason to ask: “Can we be proud of it as a nation?” However, there is rarely any consensus on this question since the views on national identity and pride are diverse and fall into two major—antagonistic—categories. Let us define these contrasting notions as ‘authentic folk’ nationalism and Eurocentric nationalism.

Exponents of ‘authentic folk’ nationalism are Maltese-speaking, proud-to-be-Maltese people predominantly of lower social standing. They express vocal pride in the achievements of the young independent state and slam criticism of its shortcomings as a deliberate undermining of Malta. They seem to hold that Malta already deserves to be on par with the rest of Europe and thus should not allow external interference into its seemingly internal affairs. Consequently, proud patriots identifying with this kind of nationalism support spring hunting (as a tradition forming part of Maltese identity) and gloat over the persistent wiping out of the Caruana Galizia memorial. After all, the slain journalist mocked everything they stand for, which makes her an alien and a traitor in their eyes.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]To the ‘authentic Maltese folk’, national pride is the ultimate virtue.[/perfectpullquote]

Combining the results of two surveys—the one that established a significant support for Joseph Muscat’s resignation terms and the other which confirmed that “half of Malta believes” he could potentially be involved in the murder cover up—we can conclude that some segments of the population do not regard gravely unlawful behavior and remaining a leader, at least temporarily, as incompatible. To the ‘authentic Maltese folk’, national pride is the ultimate virtue. Being a proud Maltese alone appears to be enough to absolve of any crime while, by the same measure, deviation from this norm or being of foreign origin is perceived as almost a crime in itself.

In opposition to the proud-to-be-Maltese folk stand people whose national pride sounds rather hesitant. This group considers Malta inferior to ‘more civilised and democratically developed’ European societies. Contrary to the content patriots, these often Anglophone, profoundly Eurocentric representatives of the upper middle class claim that Malta is not a ‘normal country’ and has no chance to reach that level without continuous supervision from the European Union.

Despite classifying Malta as lagging behind ‘civilised’ Europe, the Eurocentric Maltese are no less patriotic than the ‘authentic’ ones. They, too, bring national flags to the protests. They sing the anthem. They, too, call their opponents ‘tradituri tal-poplu Malti’. Undoubtedly, both crowds gathered on the streets on December 2—the one to block parliament in Valletta and the other outside the Labour Party headquarters in Ħamrun—were inspired by the ‘love of their country’, each taking the other for a bunch of national enemies and traitors.

In a nutshell, the standoff between the government and civil society during the last few weeks of 2019 has been a contest in patriotism. To draw another parallel, the camps invoke the defining slogans of the 2016 presidential election in the United States, paraphrased. It is “Make Malta great” vs “Malta is already great”. But unlike a declining empire where the former catchphrase wins elections, a tiny former colony responds more to the latter.

The outcome of the referendum on spring hunting in 2015 was not only a sad day for migrant bird conservation. It announced a winner in a contest for national identity and pride. ‘Authentic folk’ national identity and unabashed pride in being Maltese calls the shots—and no one in present-day Maltese politics excels at igniting it better than Joseph Muscat.

The Leader Who Made the Nation Proud

“People say he’s corrupt, but I think he’s a good leader”, a new acquaintance told me on an occasion once the conversation turned political. “He has an ambitious vision for Malta, he thinks big. I’m proud of my country more than before”. This conversation confirmed my hypothesis on the strategy behind Joseph Muscat’s popularity: boosting national pride and the ego of an average Maltese person. Staying firm under international pressure was a key ingredient in achieving this effect.

Joseph Muscat tapped into patriotic sentiments already a few years before he was elected as prime minister. Delivering a speech in Maltese at the European Parliament’s plenary session, he suddenly paused and then refused to continue after having realised that translation was unavailable. In a visibly emotional manner, he declared: “No way, you either give us really our language or ‘thank you and goodbye!” From a national pride standpoint, this was broadly interpreted as an admirable act of patriotism, while others—Daphne Caruana Galizia among them—ridiculed it as a sign of his poor command of the English language. “I’m with the nationalist party and even then I respect what Dr. Muscat did here” reads a comment on a YouTube page of the recording.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The strategy behind Joseph Muscat’s popularity was boosting national pride and the ego of an average Maltese person. Staying firm under international pressure was a key ingredient in achieving this effect.[/perfectpullquote]

Legalisation of same-sex marriage in a country with dominant conservative social values, only a few years after the divorce referendum was an ambitious move for Muscat’s administration. He found a winning strategy, however, permitting to appease the LGBTIQ lobby while retaining popular support: anyone whose religious sentiments were hurt by the development could be amply compensated with national pride. “We made history”—the rainbow message projected onto Castille rendered Malta a champion of the cause in the European Union. Since 2016, the country has been ranked the most progressive in Europe for ‘gay rights’.

National pride had another glorious moment in 2017, when Muscat took the prime ministers of Belgium, Luxembourg and Slovenia for pastizzi at Serkin. What could possibly declare a leader more patriotic than introducing fellow European leaders to staple food ingrained in national identity? There, he presented himself as a true man of the people, down to earth yet ambitious—an image every ordinary Maltese of any partisan leaning could aspire to.

Enjoying traditional #Malta pastizzi snack with #Belgium #Luxembourg #Slovenia PMs @CharlesMichel @Xavier_Bettel @MiroCerar and partners -JM pic.twitter.com/zFbjaaQ8Bu

— Joseph Muscat (@JosephMuscat_JM) February 4, 2017

Judging by the examples of Putin, Orbán, Erdoğan and, above all, Trump, domineering rulers are more successful at invoking national pride. ‘True patriots’ in power bulldoze over opponents, lest a willingness to compromise be perceived as weakness by proud citizens. Having declared his pride in being Maltese and keeping the country’s best interests at heart, Joseph Muscat scored more political points when he ignored international pressure.

Perhaps the boldest geopolitical move by Muscat in recent years was his uncompromising take on the humanitarian crisis and Mediterranean rescue missions. He was the one to call for stricter EU border security and the relocation of migrants from Malta. Speaking to national media, he also continuously emphasised that migrants taken in to Malta were indeed being transferred to other member states.

Malta’s objection to rescue vessels’ disembarkation for more than two weeks in January and April 2019 pressured the EU to step up the game and enter redistribution agreements. Former Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi publicly honoured Muscat for leadership skills and “solving the European migration crisis”—something that neither Giuseppe Conte nor Matteo Salvini were capable of. This stance must have made the patriotic heart beat with even more pride: there was a strong leader, a Maltese man who defended the country from ‘invasion’ and made the foreign counterparts respect his decision.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]One of Muscat’s favourite strategies was to present economic growth as a prime source of national pride—and his own chief accomplishment.[/perfectpullquote]

One of Muscat’s favourite strategies was to present economic growth as a prime source of national pride—and his own chief accomplishment. Even in a political climate where everything is discussed from the standpoint of national identity, selling the economy as the whole country’s success requires extra imagination. Why would segments of the population left behind by the booming economy—single mothers, pensioners and low income earners—feel proud of the economic setup that does not benefit them?

Considering that Malta’s economic miracle was sustained by underpaid migrant workers and the budget surplus was abetted by passport sales, one could expect that patriotic feelings of the majority would be hurt, not boosted. However, this is where the political genius of the former prime minister lies: he grasped that just about anything could be branded as national triumph if peppered with flashy nationalistic rhetoric and served by a strong uncompromising leader.

Even in his televised speeches and final remarks, Joseph Muscat remained true to the image of being his country’s most loyal servant. Announcing his resignation, he pledged the citizens to take pride in the young republic’s achievements. A glamorous version of the Maltese national anthem played in the background, intensifying these sentiments: it alluded to the progress of the post-colonial island state that has become modernised and is now a salient player on the world’s stage. “We have to continue dreaming, because when the PL created solutions, the country won”, he stated in his final speech as prime minister.

Even Muscat’s resignation was orchestrated in line with ‘authentic’ national identity and traditions. Instead of explaining his decision as acting according to democratic principles and assuming responsibility for implications in institutional murder cover up, he presented his exit as a sacrifice—a concept many devoted Catholics could sympathise with. There stood a father of the nation—a ruler whose trademark was keeping firm under external pressure—who had to sacrifice his career on the altar of the nation’s ‘happiness, love and positivity’. A country’s patron saint, with no exaggeration.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Instead of explaining his decision as acting according to democratic principles and assuming responsibility for implications in institutional murder cover up, Muscat presented his exit as a sacrifice—a concept many devoted Catholics could sympathise with.[/perfectpullquote]

Thus, it comes as no surprise that the majority of Maltese citizens would still see Joseph Muscat as a leader they could be proud of, despite fierce international criticism. In the eyes of proud nationals, a true patriot of his country would always be disliked by outsiders. The fact that the Eurocentric crowd regarded his postponed resignation and the infamous ‘award’ in organised crime and corruption as a national tragedy must have only confirmed the views of the proud-to-be-Maltese. In a context of antagonistic notions of national identity, what is a tragedy for one is a triumph for the other and vice versa.

Next: Finding a Common Ground for Maltese Nationalism and Calling for National Unity

Robert Abela succeeding as the new Labour Party leader and the new prime minister proves that the brand of Joseph Muscat remains largely appealing to the PL base. Standing behind Muscat ‘until the last moment’, imitating his domineering body language, the emphasis on continuity with his predecessor and being the least preferred candidate for the Eurocentric non-Labourite lobby must have all played a role in winning the leadership race with a wide margin.

While the other candidate Chris Fearne placed partisan pride above the national one (“Kburi li Laburist, kburi li Malti”) and openly stirred partisan controversy in his campaign, Abela’s partisanship was present yet more discreet. He positioned himself as a leader capable of ‘uniting the nation’, which echoed the pledges of the President George Vella. In his first public comments, the newly elected leader called for national unity, implying that the two contrasting approaches to national identity and pride must somehow come together.

How can such antagonistic perspectives unite? The most important question, however, is who is to benefit most from this unity?

Above all, national unity means uniformity and lack of dissent, which then implies that one of the opposing camps must be assimilated by the other. Given that adamant pride in being Maltese seems to be preferred by the majority, compared to self-deprecation and not-a-normal-country lamentations, it is easy to guess which narrative is to assume its formal status. In this case, criticism of the government would be discouraged and labelled as treason against the nation.

Another predictable strategy of the new prime minister could be to unite ‘the nation’ in opposition to non-Maltese residents, particularly non-European others. Robert Abela’s promise “to better regulate foreign workers” hints at this possibility. Since clamping down on a number of foreign workers is not beneficial for entreprises profiting from them, the pro-business government could further restrict the workers’ legal status to what it desires them to be—servants to the economy whose fruits is for the natives to enjoy.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Another predictable strategy of the new prime minister could be to unite ‘the nation’ in opposition to non-Maltese residents, particularly non-European others.[/perfectpullquote]

Either way, Joseph Muscat’s ‘glorious’ exit and the Labour grassroots preference for ‘continuity’ rather than change are no reason for rejoicing in democratic optimism. They decimate the likelihood of constitutional reforms and of holding the powerful to account.

Ultimately, the outcome of the political crisis proves that members of the ruling elite in Malta can, indeed, still get away with crime if the majority allows it. This is a victory for the status quo and the establishment, eager to blatantly discriminate against non-Maltese residents and all those who deviate from the prevalent brand of national identity in order to retain power at all cost.

*The total of 58% of respondents did not insist on Muscat’s immediate resignation: 43.2% agreed with Joseph Muscat’s resignation terms and 26.4% of 58.6% of those who disagreed said he should have carried on.

** 4.5% of 63.5% of PL voters who did not accept Muscat’s resignation terms.

]]>

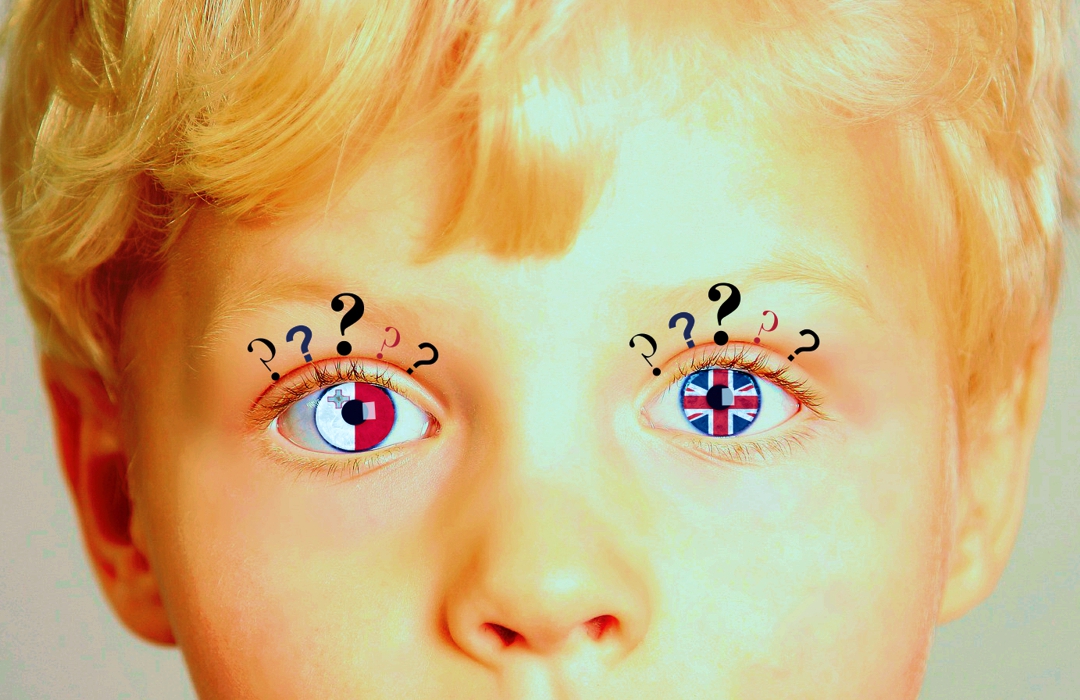

We have collected a few stories and perspectives which contemplate on how national identity is constructed and what effect it has on our lives.

by the IotL Magazine

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hat is Maltese identity? Is it a unique characteristic shared by all Maltese-born persons? Is ‘Maltese-ness’ defined by religion, symbols, language or, perhaps, a surname? Could it be that ‘Maltese identity’ is far more complex than a set of fixed habits? Finally, how do newcomers see Maltese identity and how do they relate to it?

Exploration of what lies beyond the question of national identity has always been one of the keenest interests of this publication. We have collected a few stories and perspectives which contemplate on how national identity is constructed and what effect it has on our lives.

![]()

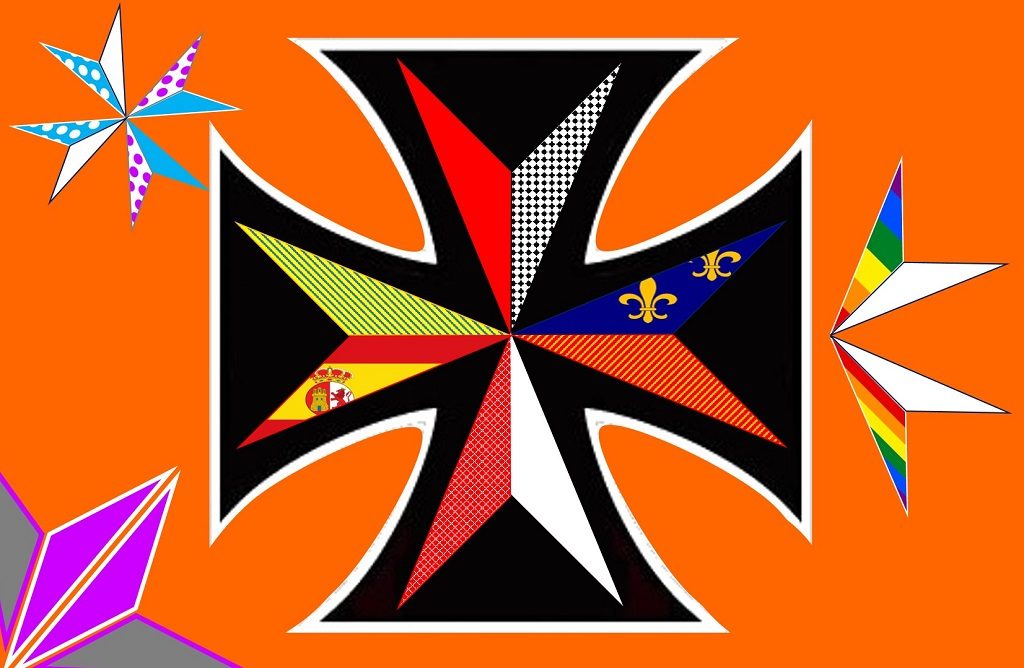

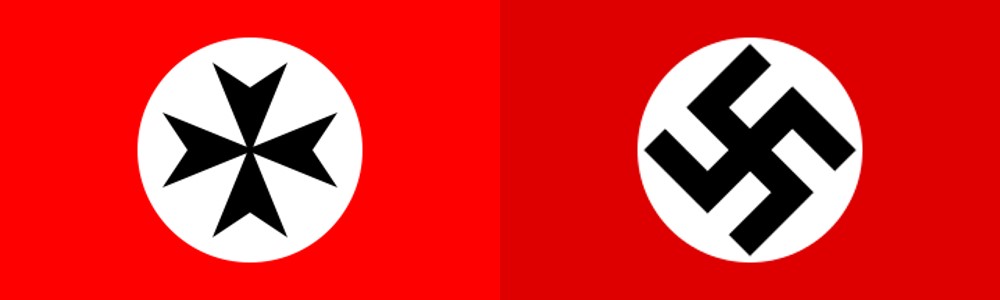

1. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Symbols?

‘The Not-So-Maltese Cross‘ by Michael Grech

Today, the eight-pointed ‘Maltese’ cross is broadly recognised as ‘brand Malta’. It is everywhere: from tourist booklets, to the crib on Triton Square and to the Malta Blockchain Summit. However, the cross of the Order of St John was not embraced by the Maltese during the Hospitallers’ rule.

So how did the emblem of debauched foreign aristocracy become the ultimate symbol of Maltese identity? In his essay ‘The Not-So-Maltese Cross‘, Michael Grech argues that the Maltese Cross became a means to emphasize, exaggerate and at times invent Malta’s historic ties to Europe. In other words, the Cross reimagined Maltese identity as European and served to distance the country from its Semitic heritage. Read more here.

![]()

2. Is Maltese Identity Defined by a Place of Birth?

‘How Growing Up in Malta and England Changed My Understanding of Identity‘ by David Edward Zammit

As a five-year-old, I was transplanted for a year or so from the village of Paola, where my parents had started to raise me up as an ordinary Maltese speaking toddler, to Oxford in the UK. There I attended Wolvercote primary school while dad worked on his PhD and mum worked as a pharmacist’s assistant.

In 1975 and 1976, we lived in a culturally diverse block of apartments, called Summertown House, on Banbury road; sharing the block with other student families from a range of national backgrounds. Irish, Japanese, Israeli, Swedish and Indian children stand out in my recollection of the common playground. Although this was a relatively short period, it was a personal watershed; mainly because my experiences forced me to switch from being a Maltese to an English speaker and to develop an interest in reading. Both characteristics have stayed with me until the present.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Upon returning to Malta after a year in Oxford as a five-year-old, I had to face the challenges of integration all over again.[/perfectpullquote]

Upon returning to Malta after a year in Oxford as a five-year-old, I had to face the challenges of integration all over again; made worse by the fact that I had completely forgotten Maltese and my parents were living in Sliema. This seemed to be a world away from my memories of Paola and Malta’s “Deep South.”

These experiences have made it difficult for me to commit to a single homogenous identity and have also given me a strong sensitivity to the way in which individual identity is constructed by the gaze of the other.

Read more here.

![]()

3. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Religion?

‘But, Where Are You Really From?’ Reflections of a Maltese Muslim on Belonging and Identity by Ibtisam Sadegh

‘I am Maltese,’ I assert to those who cynically question or glare the instant I pronounce my Arabic name or refuse to drink an alcoholic beverage. ‘But, my father is Libyan and my mother is Maltese,’ I add, when the sceptical or the curious refuse my answers, take guesses at my roots or demand further clarification. The response to this reply could range from polite silence and acceptance, to the friendly ‘I have a Libyan/Muslim friend,’ or the most certainly absurd, ‘I can see it in your eyes!’

I grew up seeing my migrant father being bluntly discriminated against, treated as if he were an outsider and a parasite siphoning on Maltese society and this despite his having lived here for over three decades, his fluency in the Maltese language (although with an obvious Arabic accent), Maltese citizenship, wife and kids.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]I thus learned from a young age the necessity to continuously navigate my Muslim background, maneuver my identity and emphasize my Maltese-ness.[/perfectpullquote]

I thus learned from a young age the necessity to continuously navigate my Muslim background, maneuver my identity and emphasize my Maltese-ness. Such daily strategies include me explaining the meaning behind my given name; at times even de-Arabizing it by abbreviating it to ‘Ibti’ or writing inquiring emails in formal Maltese—all in attempt to be recognized and treated as equally Maltese.

Read more here.

![]()

4. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Surnames?

‘Go Back to Your … Gozo?‘ by Raisa Galea

To some people, my surname seemed more important than the causes I wrote about.

When after my wedding I was able to choose whether to adopt my husband’s family name, the decision came quickly.

If my foreign surname fed into prejudice—if it truly was an obstacle to sound debates—then a Maltese surname was an opportunity to support just causes without prompting unnecessary animosity. The experiment was a success.

If Raisa Tarasova (a Russian) was told to return home whenever she protested an ODZ development, the very same arguments stirred engagement when they came from Raisa Galea (an ordinary Maltese). The contrast in feedback was so stark, it called for an investigation of its own. I decided to find out whether this was a common experience that other foreign residents encountered after having adopted their Maltese spouse’s surname. The findings were even more insightful than I expected.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]While foreigners who take on their Maltese spouses’ family names gain an advantage, Maltese adopting foreign surnames are subsequently alienated from public debates.[/perfectpullquote]

While foreigners who take on their Maltese spouses’ family names gain an advantage, Maltese adopting foreign surnames are subsequently alienated from public debates.

Read more here.

![]()

5. Is Maltese Identity Defined by Language?

‘Malta’s Language Puzzle: Malti vs English‘ by Michael Grech

Malta’s language question has been a subject of an ongoing debate for over a century. Today, our native tongue might be appropriated for some sinister purposes.

According to some individuals, one area where immigrants are ‘taking over’ is language: the inability of a number of them to speak Maltese is regarded as a failure to ‘integrate’ and a threat to an essential feature of ‘Maltese identity’. Calls are being made to stop using English to ‘accommodate them’; forgetting that this language has been constitutionally recognized by Maltese representatives as an official language alongside with Maltese. The argument seems to boil down to ‘either learn Maltese or leave’.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]How can we support the use of the Maltese language while not letting it become a tool of xenophobia and racial exclusion? Promote bilingualism![/perfectpullquote]

There is nothing intrinsically ‘anti-Maltese’ in English per se. We should point out that the dichotomy between the two languages is relatively recent and was created by people who were generally opposed to working class advancement. The elite would probably have no qualms about adopting pristine Maltese as a mark of distinction if it were to serve their segregationist purposes in the future, just as their forefathers had dumped Italian without batting an eyelid when it became convenient.

Read more here.

![]()

6. Is it Possible to be a Non-Maltese and a Local at Once?

‘How I Have Become a Local in Malta: On Local Foreigners and Foreign Locals‘ by Raisa Galea

After many years in Malta, separating my own experiences from those of the locals feels uncomfortable because I have become a local myself.

To integrate was to recognise the diversity and the complexity of Maltese society. I could no longer utter a phrase like “all Maltese are rude” or “all Maltese are racists” because I knew it was not the case. Maltese are different—a platitude from Captain Obvious which was not at all obvious a few years ago. I thought I could define fairly well what a ‘lack of integration’ means: inability to recognize diversity of a host society.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It is the relationships with the locals—Maltese and non-Maltese, uncaring and sensitive—that make me part of Malta’s social fabric.[/perfectpullquote]

It is the relationships with the locals—Maltese and non-Maltese, uncaring and sensitive—that make me part of Malta’s social fabric. I admire Malta of green fields and colourful balconies as much as I am repelled by the ever-expanding construction sites and the corporate developments. I sympathise with the Maltese who struggle to afford their rent and barely make their ends meet (just as do my relatives back in Russia) as profoundly as I decry the market-worshiping developers and tax-dogging companies.

Read more here. You can learn more about the author’s experiences of integration from this episode of Good Faith Podcast with Christian Peregin.

]]>

Contrary to what many want to make us believe, this republic is far from immaculate. Acknowledging this might help us resist the dirtier among us.

by Kurt Borg

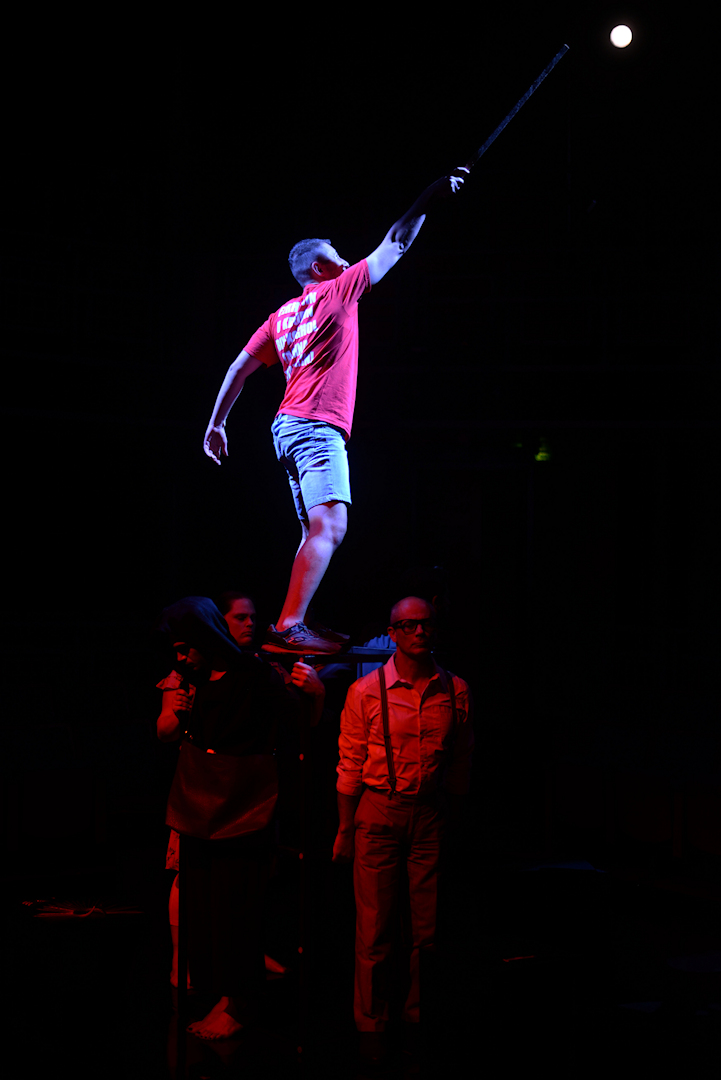

Image: Still from Repubblika Immakulata promotional video (amended)

[dropcap]A[/dropcap] General election, a wedding and the local feast. On the same day. Within the same family. No one wants to give in. And whilst everyone tries to hold on tight to the traditions that make us who we are, no one wants to accept that in Malta, we are no longer what we used to be.

So went the tagline of Repubblika Immakulata, the latest theatre production by Dù Theatre, written and directed by Simone Spiteri. RI is a political tragicomedy that provided a critical snapshot of contemporary Malta and was on everyone’s lips for this month. Well, not everyone’s; after all, the audience for RI was the typical Spazju Kreattiv crowd. So, no matter how well-written, smart and witty, it ultimately was a play addressed to people who more or less already agree with the play’s main idea: namely, that there are some dirty things going on in Malta.

Usually I feel that Maltese plays suffer most in the script-writing but thankfully this was an exception. The writing was flowing and scenes were well-executed, even if the second half was slightly dragging. This review will not discuss the plot and the characters in much length, but will engage and analyse some of the play’s main messages (*).

Online Reactions

Let’s start with some reactions to the play on social media (**).

Some hailed the play as required reading for the nation, suggesting that the play should be included in the educational curriculum. Others critically remarked that despite the sombre message of the play being very obvious, sections of the audience seemed to prefer laughing at the vulgar jokes. One viewer remarked on the slightly excessive parody on the “usual ħamalli” and “tal-pepe”, prompting the crowd to laugh hysterically at the cheap jokes.

These others felt that the characters of the play were too extreme (or, perhaps, intentionally clichéd), depriving the overall message of subtlety. Also, these others said that whereas the play did not hold back when it came to vulgarity, it still held back (censored itself?) when it came to directly mentioning specific political parties or politicians.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The scene which foregrounded the auctioning of a statue of Saint Mary against a background of the siblings deliberating the price for their father’s house highlights the complicated relations between religion, family and money in this island.[/perfectpullquote]

It is true that the point of the play was not to point fingers at a specific political party, lest it be unjustly labelled partisan, but also because the message of the play seems to have been more directed at a general political culture. On a more positive note, many praised the scene which foregrounded the auctioning of a statue of Saint Mary against a background of the siblings deliberating the price for their father’s house, highlighting the complicated relations between religion, family and money in this island.

Archetypes or Caricatures?

In an interview with Teodor Reljic, the playwright Simone Spiteri suggests that the main protagonists of the play were intended as archetypes. And perhaps it is for this reason that they appear too unrealistic or homogenised.

The three main characters are David [Mark Mifsud] (the next ‘big shot’ in politics, who schemes with a businessman in order to ensure his election), Franklin [Andrè Mangion] (a hardcore festa enthusiast, a seemingly shallow person whose meaning of life depends on the festa), and Petra [Magda van Kuilenburg] (a woman who feels pressured to marry despite her partner being abusive).

Tensions are high among these three siblings as their big day coincides: the election is being held on the same day of the village festa, which also happens to be Petra’s wedding day. For two hours, the audience lives through the various hassles these three characters go through as they juggle their personal interests with family expectations.

The play seems to suggest that, despite being excessive caricatures, the audience can relate to the characters. In fact, the play closes with another character (Anon; we’ll come back to him(?) later) “breaking the fourth wall” and asking the audience whether they could see facets of themselves in the different scenes. In response to the silence, Anon prompts the audience—asking “are you sure?”—wanting to suggest that we all form some part of this major hassle despite our not wanting to believe so.

Anon: A Buried Voice of Reason

Anon (excellently portrayed by André Agius) is an interesting character. His (I’m using a male pronoun, but the character was quite post-gender and it would perhaps make more sense on various counts to use the singular they) Anon-ymous character plays a liminal role, being both another sibling immersed in the plot, as well as a detached “voice of reason” who analyses what’s going on in the play and communicates directly with the audience. Anon is the voice of critique who—in a memorable scene towards the end—is buried by the rest of the characters who would rather not listen to critique.

In fact, whereas all characters seem to lack a sense of self-reflexivity and seem to be deeply immersed in their situation, Anon is able to consciously reflect on what is going on. For this reason, it is Anon – rather than any of the other characters—who probably resonates the most with the crowd since he is able to adopt a critical and ironic distance.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Anon is the voice of critique who—in a memorable scene towards the end—is buried by the rest of the characters who would rather not listen to critique.[/perfectpullquote]

At the risk of sounding patronising, it could be said that the play is hinting at a basic inability of the Maltese public sphere to reflect critically on itself without neither descending into a categorical snobbing of “anything Maltese” nor uncritically celebrating how awesome Malta is. In this land where, as Anon puts it, everything is seen as blue or red, nuance is seriously missing.

The “Bad Guys”

With that said, the play makes an important point on another type of character who is able to have a distance from the situation, albeit a very cynical distance. In RI, the character of Albert (portrayed in an annoyingly convincing way by Pierre Stafrace) represents the businessman who thinks—not inaccurately—that he can own the politician.

This is the character who—without any apologies to Marx—believes that beneath all politics lies economics, and thus uses economic power to influence political realities. These are the characters who think they’re oh-so-wise and that they can dictate matters “from behind the scenes” because they know better, and know how the crowd reacts, and they know “what’s what”. Albert is the kind of guy who, when shit hits the fan, will gather his people and figure out how to spin a story and fabricate matters; he will tell you exactly what the next move will be and the subsequent one. Even the politician bows down to Albert; whereas David patronises his siblings, he is as meek as a lamb with regard to Albert.

I confess that this is the aspect of the play which hit me the hardest.

These, to me, are the serious problems of this immaculate republic. The same person who said that RI needs to be required reading for the nation also recognised that this will never be the case since they will oppose it. This question of who they, the “bad guys”, might be is interesting. Although, theoretically, I know better than to impose such a moralising “good guys/bad guys” discourse, impulsively I think that perhaps we need not dismiss it outrightly.

The play made me reflect more on this: clearly, many people I know (activists, academics, ordinary folk, even some government officials) aren’t like the bad guys.

The bad guys are real estate moguls advising us ordinary folk that we’d be happier if we lived in smaller properties; the bad guys are those who do not understand why it’s ludicrous to suggest that it’s OK to rent out a room to shift workers for 12 hours, with tenants switching after 12 hours to make way for another shift worker; the bad guys are the businessmen-turned-politicians who are unable to differentiate the two (or, rather, see them as extensions of each other). The list goes on.

Must Critique Be Moralising?

RI tries to spell this out—albeit a bit ambiguously—in the culminating final scene, which consisted of a poetic and impassioned speech by Anon addressed to the audience (***).

The jury is still out on this final scene. “Perhaps a bit too preachy and spoon-fed,” some said; “absolutely necessary to the play,” others retorted. Some felt that the speech was too didactic and moralising, while others saw the scene as the crux without which the whole point of the play wouldn’t have come out well. I do not think that this speech was absolutely necessary.

Actually, I think that the same impulse of the speech could have been better distributed throughout the whole play (in the spirit of “show, don’t tell”) especially since, at times, it wasn’t always clear where the play was going ideologically. Except for the implicit critique of excessive construction and the obsession with raising towers, I think that without that final speech which spells out the play’s “agenda” a bit too clearly, I fear that the play might have lacked a solid ideological backbone.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Without that final speech which spells out the play’s “agenda” a bit too clearly, I fear that the play might have lacked a solid ideological backbone.[/perfectpullquote]

Without that speech, the play might have been another somewhat satirical portrayal of Malta’s quirks (in the vein of “haha this is how we are”) without digging deeper into how far the stench goes.

With that said, however, I was not irked by the final speech as it had a cathartic effect of hearing something most of us (at least, most of us watching the play or reading this review) live through everyday being vocalised in such an impassioned manner. The speech clearly foregrounds the severe contradictions Malta is living in. Here is a brief excerpt from the speech, where Anon refers to “Il-Malti”:

Li jisloħ rkoptu l-quddies imma jweġġa’ b’ilsienu lin-nies. Li jipprotesta l-moħqrija t’annimal imma ma jara xejn ħażin b’mitt refuġjat f’razzett jgħix qisu bagħal.

Anon’s speech goes on by turning the guns from these “hypocrites” to the audience itself. Anon discomforts the crowd by sarcastically saying that we all feel excused and exempt from this criticism since we’re all-too-pure and innocent, and not part of that dirty gang of Maltese. If anything, it is this sentiment which I think the play doesn’t get quite right. I do not think that the best reaction to the nasty national state of affairs portrayed in the play is to level the grounds of complicity as if we’re all equally complicit and guilty. Ultimately, social critique need not be an exercise in collective guilt and shaming.

However, the play does well in deconstructing the myth of Malta as naive, innocent, pure and charitable. We’ve grown up alright—look at us leading the way in Blockchain and crypto stuff; look at some of us excusing dodgy offshore financial arrangements because “after all, the country is doing OK”; look at some of us say that it’s understandable that people are tempted to continue building towers of apartments with ever-increasing rent prices “because that’s what everyone is doing”; “make hay while the sun shines”; “U ejja come on, you’re going to ask me these questions in the morning?”

The play highlights how there’s something very wrong in this normalisation of everything. Sometimes we feel the need to shout out “STOP ALL THIS”. RI hints at this frustration, not because it has its own clear political program to put forward, but out of a felt sense that there’s something ridiculously wrong with all this. However, this political rage has to be channelled outward toward the real targets and not internalised in order to send the audience on a guilt trip.

All in all, through its characters (and, sometimes, despite them) the play scores highly in its attempts to not just portray Maltese society through a critical lens, but also—in reference to the title of the play —to drive the point home that, contrary to what many want to make us believe, this republic is far from immaculate. Acknowledging this might help us resist the dirtier among us.

* For a ‘more standard’ review, see this article which gives a good account of the play, considering it’s Lovin Malta (I’m sure LM can take the jibe, especially after the parodic portrayal of them in Repubblika Immakulata).

** Most of the reactions to the play I mention here were obtained from Facebook. However, since I don’t consider informal Facebook statuses to constitute news items or official sources, I hesitate to identify these individuals or provide a link to or a screenshot to their Facebook profiles. With that said, if anyone reading this recognises their opinion being represented in this review and wants to be identified, do get in touch.

*** Many thanks to Simone Spiteri who sent me the text of this speech while writing this review.

]]>

The core issue that underpins the conflict in Great Siege Square is whether the memory of the slain journalist can claim a place on the emblem of nationhood and whether she can be considered as part of the Maltese nation at all. It is the meaning of ‘the nation’ and who deserves to define it that is being contested.

by Raisa Galea

Collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]“[/dropcap]No, they have to clear it up!”, James*, a Valletta resident and a (moderate) Nationalist Party supporter, told me over a beer one November afternoon. He was referring to vocal supporters of Daphne Caruana Galizia who were defending a makeshift memorial to the slain journalist on Great Siege Square in front of the Law Courts from the government’s attempts to remove it.

This conversation took place when the conflict had reached a culminating point. On November 7, 2018 another physical barrier—a line of metal fences—had been erected in front of the memorial site, thus preventing any access to it. For a few weeks, every attempt at restoring the makeshift memorial had been shut down by the state: all commemorative items, from candles to banners were immediately removed by government workers as soon as they had been placed there.

The Great Siege Memorial Strife

By mid October 2018—the first anniversary of the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia—the flowers, candles and written tributes left at the foot of the Great Siege Monument to honour the journalist had been taken away at least 17 times.

The strife began to intensify in late August to early September 2018 when acts of vandalism on the memorial became more frequent. Access to the Monument by Antonio Sciortino was sealed off immediately after the celebration commemorating the Great Siege on September 8. The formal explanation for this decision was the need for the restoration of the bronze statues’ granite base. Activist groups Il-Kenniesa, Civil Society Network and Occupy Justice protested the closure and continued placing commemorative items outside the protective screen.

The conflict received contrasting responses locally and overseas. The government’s actions caused outrage internationally: authorities, NGOs and prominent personalities expressed their concern about the repeated destruction of the memorial, absence of a “meaningful result in the investigation beyond arraigning three suspected hitmen” and the state of press freedom in Malta. Activists claimed that the government instigated hatred of its most vociferous late critic and encouraged mob rule. PEN International Executive Director, Carles Torner was reported to have said that “even in dictatorial states like Turkey or Russia, the Government wouldn’t just remove a memorial 20 times.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Activists claimed that the government instigated hatred of its most vociferous late critic and encouraged mob rule.[/perfectpullquote]

On the other hand, support for the activists did not seem widespread among the Maltese population. In some cases, citizens even actively contributed to the clearing of the memorial. What was the reason behind such a reaction from a rather sizable segment of the population? Moreover, one has to ask: why do calls for public inquiry into the assassination find so little support from individuals outside the activists’ groups and are even rebuked by some?

![]()

James, with whom I was discussing the events, makes his position clear. He wants the makeshift memorial away from the Square.

Unlike Labour party spokesman Glenn Bedingfield, who can be expected to applaud the government’s decision, James criticises the Labour administration on most issues, except this one. When I remarked that the protestors’ demands for justice were rightful and that they indeed had a right to commemorate Caruana Galizia in that particular location in front of the Law Courts, he gestured disapprovingly. “They should go somewhere else—Sliema, St. Julians, Attard. There are plenty of other places. This is a national monument. They can’t keep it for themselves”.

The Great Siege Monument, a Symbol of National Identity

The Great Siege Monument in front of the Law Courts is an accolade to Maltese nationhood. Sculpted by Antonio Sciortino in 1926 during his stay in Rome, the bronze statue was inaugurated in 1927 by prominent representatives of the state and clergy who delivered their speeches in Italian and Maltese.

Taking into consideration the political climate in Italy in the late 1920s, the rule of the then pro-Italian Nationalist Party whose ranks included a Mussolini-supporting faction and the symbolism behind the three bronze figures—Faith, Fortitude, and Civilization (themselves conservative and nationalism-inducing allusions)—the sculpture conveyed deeply nationalistic connotations at the moment it was unveiled.

The nationalist implications of Sciortino’s sculpture are further intensified by its link to the Great Siege—an event that serves as a tool for the construction of national pride in Malta and is often alluded to by nationalists of various colours in order to advocate for Maltese nationhood as Christian and European and thus opposed to non-European others.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]The nationalist implications of Sciortino’s sculpture are further intensified by its link to the Great Siege —an event that serves as a tool for construction of national pride in Malta.[/perfectpullquote]