The parkers are our modern working class entrepreneurs. The parkers, like the developers, landlords and ministers understand the market too well. The parkers managed to carve out their own jobs just at the right time in a neo-patronage system.

by Rachael Scicluna

Image: a still from a YouTube video, redesigned by Isles of the Left

[dropcap]H[/dropcap]istorical and anthropological analysis have pondered for centuries on what ties Mediterranean societies together—is it landscape, food, the honour and shame syndrome or hospitality? I dare say that besides morphological and historical commonalities, what escaped many historians and anthropologists, is that ‘we’—the Mediterraneans—are a culture based on concealment and non-declaration. Such understanding might have gone unnoticed because the authors doing the analysis come from Anglo-Saxon and Nordic worlds. In what follows, I use the role of the car park attendant in order to analyse first, the birth of a new entrepreneur in a post-industrial society. Second, I use the car park attendant as a lens to think about Maltese society at large. But also, to look for those meaningful and hidden connections that might link us to other Mediterranean societies.

Importantly, I see the first indicators of people and thinkers re-claiming the concept of the Mediterranean and moving away from that of Europe. Could this be resurfacing because we are passing through political and socio-economic struggles? Are political borders shifting? Is this a collective regression to an identity that gives us some form of ontological security? Or is it a conscious mental shift that is reconsidering the social experiment of ‘Europe’ and a different way of doing politics?

The Car Park Attendant

How can we think through such a big political and existential concept by using the role of the car park attendant (‘parker’ hereafter) who is often thought of a unilaterally pejorative nature? Many think that this role is unnecessary. It is largely assumed that on the one hand the parker makes a lot of money and on the other, they do not declare their income, despite the fact that the Malta Transport Authority states that they are still subject to inspections by the Tax Compliance Unit. Additionally, there is an aura of fear where it is often assumed that if you do not have the ‘optional tip’ your vehicle may be in danger.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Don’t our ministers too do that and worse?[/beautifulquote]

But, aren’t we a culture of concealment and non-declaration? Don’t our ministers too do that and worse? Isn’t the case of the Don’t Bury Us Alive! a reflection of a culture that does not comply to officialdom and laws. This is not the sole case. Additionally, don’t big landlords invest the deposit money taken from the tenant in order to get bank interests and construct more shoeboxes-for-homes? Therefore, the cunning practices and the worldview of the parkers can be thought of as a microcosm of our nation, not an exception.

Despite that such stories of non-declaration (and abuse) by the parkers may hold some truth if not envy, this article is a playful curiosity in seeking to understand how this role emerged in our society. It is not about whether the role of the parker is good or bad. Instead, I want to analyse this role from an entrepreneurial perspective in relation to a changing society. Can this role make us think further about the way our society is adapting to new economic and political shifts? Let’s stop to think for a moment about the emergent role of the parker.

Changing Society, Changing Market

How can the role of the parker be sustained in our contemporary society? In order to understand this role, we must first understand the local social structure. Lately, I have been reflecting on the impact that the shift from industrial capitalism to neoliberalism had in Malta. In a country where alliances based on friendship and family networks were always key, one cannot think of ‘pure neoliberalism’. It is best to think of our society as a cross between neoliberal and patron-client kinds, based on a strong kinship system—that is, a neo-patronage society (my term).

Not only did industrial capitalism change seasonal time to chronological time, but it also created ‘empty homogeneous spaces’ that could be filled up by any employer. All one needed is to be trained and disciplined. These industrial jobs, of course, should not be totally demonised as they brought prosperity to some and freedom to others. With the pull of industrial capitalism, the penetration of the free market and globalisation, new white collar jobs were created—such as, the receptionist and the IT officer. Others, like the clock-maker, shoemaker or the oven-builder, have become anachronistic. However, such transformations are neither good nor bad. Societies are not static but always shifting and changing across time. Thus, roles and duties change according to time and space; and so does morality.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The role of the parker is a creative and ingenious engagement within the strictures and structures of late capitalist modes of production.[/beautifulquote]

What is of utmost interest for this analysis is the way certain jobs are created outside of the economic normative pull. Here, I come back to the parker. There was no business plan that designed and implemented such a role. It was a direct reaction to a changing society which was thriving economically. To me, the role of the parker is a creative and ingenious engagement within the strictures and structures of late capitalist modes of production. Inasmuch as late capitalism has brought about social and economic changes which had an impact on the household, family formation, gender roles and ultimately in the sphere of employment, Maltese society did not embrace capitalism in its totality. Instead, the capitalist mode of production and now neoliberalism were moulded to fit our friendship and family networks. These networks shape the very core of our existence and especially our perception of money, business and all practices related to it are understood and practiced.

The role of the parker was carved out precisely in that ‘in-betweeness’, that economic and social shift which resulted in a neo-patronage society. Unlike the baby-boomers, the X-generation and the millennials are faced with precarious and short-term employment contracts. This brings out our survival skills where such precarity and uncertainty is countered for by making ‘a quick buck’ when one can. The parker is a direct reflection and engagement with such social, economic and political transformations.

The Parker as a Creative Entrepreneur

Cars are undoubtedly a symbol of industrial capitalism. Objects and machines are not banal. They are fraught with social and political meaning. Cars fall straight in this symbolic and functional category. Nowadays, cars are social capital and a ‘coming-of-age symbol’. Cars and car parks have taken over the island and are embedded in our daily rhythms. Nowadays, even a house loses credit if a car park is not included into its design. It is this existential and philosophical shift that the parker so ingeniously understood. Thus, the parker was cunning enough to create a job, a service and a need which did not exist previously .

This type of creative engagement is inherent in our social skills as Maltese. And the parker is only a reflection of such an endeavour. This perhaps relates to the succession of different colonisers, where the majority of the Maltese have had to creatively deal with such continuous domination. The master-slave syndrome among the Maltese people is a learnt introject coming from our historical background of always being colonised. However, beneath this façade, we are a nation of survivors. Colonisation brings hardship. And hardship and struggles often push certain groups, like the working-classes and the just-coping classes to the fringes of society. Living at the periphery gives one the opportunity to look at the world with different eyes. It is what brings about creative endeavours.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The parkers are our modern working class entrepreneurs.[/beautifulquote]

Additionally, this ties in with our cunning skills as industrious entrepreneurs (bieżlin). This is then justified and neutralised through its moralising principle—we make a quick buck when we can because we are doing it for the greater good of our families. In fact, I befriended the three parkers who work on different shifts where I leave my car key on a daily basis, and soon found out that they are two brothers and a son. The family network is strong and solidarity amongst them is real and evident.

In general, the Maltese feel that they must gain as much as possible from this national and ‘one-off economic bliss’ because tomorrow lies in the unknown. The parkers are our modern working class entrepreneurs. They are also our existential-economic-experts. The parkers, like the developers, landlords and ministers understand the market too well. The parkers managed to carve out their own jobs just at the right time in a neo-patronage system.

This does not mean that parkers are using ledgers, but follow their intuition, street-wise experience and sentiments in order to achieve what they did. We really are not a society of numbers. Numbers are a myth—purposely left as such! This suits our culture of non-declaration. I believe that such cultural practices are not unique to Malta, but are similar to other Mediterranean societies. Is it practices of non-declaration and concealment that links the Mediterranean together? Maybe.

]]>

It is not the ‘ugly and stupid’ art that needs to be smashed and never sent for repair, but the insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

by Raisa Galea

Picture by the author

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ust as it happens with most topics in Malta—from over-development to fast food adverts—the disputes about the quality and the place of art in the society quickly become absorbed by customary narratives: partisan rivalry and the country’s purported status of the ‘citadel of mediocrity’. Despite their dull uniformity, these disputes are worth looking into—they could suggest how Maltese people tend to relate to each other and to the outer world.

To begin with, public access to the arts in Malta is limited: Only a few places such as Spazju Kreattiv at St. James Cavalier, Malta Society of Arts and MUZA (a project still in the making, previously known as National Museum of Fine Arts) welcome the general public—that is, the majority whose professional and consumption interests are not directly linked to the arts. Other than that, contemporary artworks are displayed at art events, of which there are plenty. Most frequently, art is showcased at private exhibitions and book launches which, by default, imply their secluded or commercial nature.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences.[/beautifulquote]

Engaging with the art at social events cannot be contemplative and serene due to the confines placed by an informal code of conduct that the attendees are expected to uphold. The art circles’ membership is available to the candidates with the right family background, the ‘appropriate’ occupation, distinct dressing style and ‘tastefulness’ of overall consumption preferences. That turns events-going into a hollow performance aimed to affirm the social status of attendees which has little, if at all, to do with the art.

Artistic experiences in Malta are also profoundly shaped by the country’s minuscule size.

In a small, densely populated country, a person usually meets artists before their works, unlike in the majority of larger states where pieces can be seen as anonymous and independent from their creators. The proximity to the artists is more likely to separate the general public from the art. It either results in a few fan clubs surrounding the artist or, on the contrary, the audience rejects the works straight away because they are repelled by the artist’s persona. Had Picasso lived and created in Malta, with his reportedly bad temper, he would have never gained any recognition for his works locally, in such proximity to the potential audience.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Nepotism, patronage of the governing elites, the lack of transparency in the process of allocation of public funds all create an ambiance of distrust which does not help promoting the arts.[/beautifulquote]

The partisan rivalry pervades practically every sphere of the Maltese society and the public perception of the arts is no exception. Nepotism, patronage of the governing elites, the lack of transparency in the process of allocation of public funds all create an ambiance of distrust which does not help promoting the arts. For instance, given that the Chairman of Valletta2018 Foundation and its Artistic Director are both Labour Party’s appointees, the V18 activities are bound to be trashed immediately, regardless of their quality, especially by the PN’s die-hard supporters. A fair critique of patronage is then brushed away as ‘elitist’ (and this excuse is accepted, mainly due to the prevalence of conservative takes on art in Malta).

Thus, the layers of individual, partisan and class biases are the obstacles between the artworks and the public.

In such circumstances, open air art displays could have been a remedy. Anonymous and open for everybody to contemplate on, they could bring art closer to the public and enrich our daily experiences. Instead, once introduced to the public space, the installations are instantly seized by the ‘taste police’ who asses their appropriateness to represent Malta’s creative potential. Worse, if the artworks do not meet the expectations of this informal ‘ministry for aesthetic standards’, they risk to be vandalized.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Denigrating another is the easiest way to assert one’s own virtue and that is exactly what the members of Malta’s ‘taste police’ live for.[/beautifulquote]

Whether it is due to its provincial status or the remnants of colonialism, the cultural scene in Malta seems to be in a perpetual reaction to the label of mediocrity placed on it by a number of Maltese. To the ‘aesthetic police’, there can be one and only ideal of ‘Culture’—that of a cathedral of supreme sophistication whose doors should be shut for ‘tasteless plebs’. Denigrating another is the easiest way to assert one’s own virtue and that is exactly what the members of Malta’s ‘taste police’ live for.

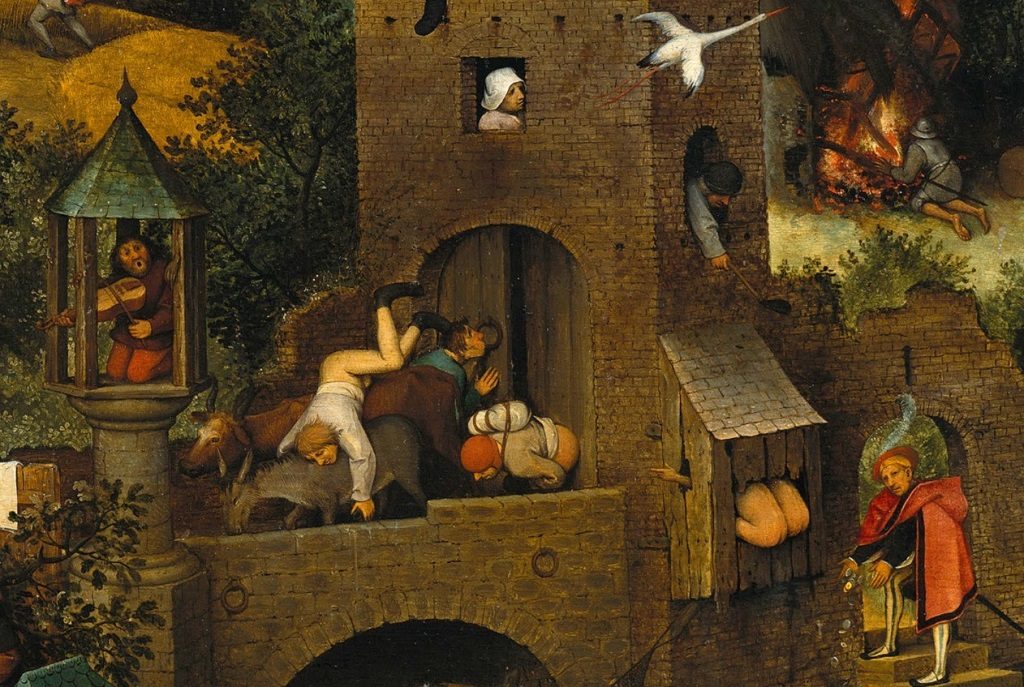

The eagerness of some individuals to stress their disdain for mediocrity reaches the level of absurd. I recall an opinion of a Maltese art enthusiast about Bruegel. Apparently, I learnt, the Flemish painter was a mediocre artist because his works were ‘cluttered’ and did not abide by the “less is more” dictum. Since not even Bruegel’s Dutch Proverbs seem to be up to the ‘standard’, the V18 Kif Jgħid il-Malti project which translated Maltese proverbs into art, was destined to insult the aesthetic sensitivity of ‘taste warriors’.

Habitually, the dispute focused entirely on the surface of the artworks. Their polystyrene medium was more worthy of a debate than their symbolic meaning. Hardly was it pointed out that the carnivalesque figures were well-timed to the Carnival—itself a feast of mockery and grotesque exaggeration. In my opinion, the project succeeded to achieve what it aimed for—the playful, quirky, cheeky and elementary outlines of these sculptures had brought the proverbs to life. The metaphors became tangible.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Those who ‘stick their nose between the onion skin’, who intrude into affairs of others, become tainted—and that is precisely what the sculpture conveyed.[/beautifulquote]

The sculpture of the man with the head stuck in the onion captured “bejn il-basla u qoxritha” perfectly well. Those who ‘stick their nose between the onion skin’, who intrude into affairs of others, become tainted—and that is precisely what the sculpture conveyed. It carved out the image of a gossiper. It ridiculed the intruder. It need not be more sophisticated because the proverb itself is coarse and direct. And, I believe, its honest primitivism surpassed the unimaginative critique that denounced it.

It seems plausible that the ‘folk crudeness’ of these sculptures alone was capable of provoking fury, leading to vandalism. It could be that the ‘taste warriors’ volunteered to swipe the European Co-Capital of Culture clean of ‘jablo junk’ a few hours after it had ‘contaminated’ Valletta. Bizarrely, the move was applauded by Mark Anthony Falzon, a prominent intellectual, who stated that “the vandalism of stupid ugly things in public spaces is not in the least distressing”. I hope that insecure conservatism that judges the art entirely by its surface appeal can also be considered ugly and stupid. That way it can be smashed and ditched straight away with no apologies offered.

When public art displays—sophisticated or crude—are scarce, having more of them is vital. Let them be ‘beautiful’, ‘ugly’, ‘noble’ and ‘profane’. Simply let them be.

Perhaps they succeed to stir curiosity and spark a few conversations. One day, these conversations will delve into symbolic meanings and wake the ephemeral beauty deep within each one of us. But first, the public needs to acquire safe access to the art; and the open air installations are fit for this mission best, because they create a space free from the partisan and social class confines. This democratic access to the arts, too, must be guarded from the dominant conservative perceptions that infinitely seek to segregate the ‘noble and beautiful’ from the ‘ugly and profane’. Valletta 2018 does not need more insecure conservatism which, frankly, is way too provincial to be part of the European Co-Capital of Culture.

![]()

The article borrowed an argument from the author’s earlier piece.

]]>

To integrate was to recognise diversity and complexity of Maltese society.

by Raisa Galea

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] admit I am no longer the same person who came to settle in Malta in 2009—the years of immigration have significantly altered my perceptions of the world. I did not change alone though—these past few years Malta itself has been through a speedy transformation. The faster pace of life and the swift cultural changes have certainly influenced the perceptions of many locals, too. In other words, none of us—neither me nor the locals—are the same as we were back in 2009.

After 8 years in Malta, separating my own experiences from those of the locals feels uncomfortable because I have become a local myself.

The Phases of Integration

I clearly remember my first couple of years in Malta—the years of struggling with bureaucracy which made me feel unwelcome. Those years (let’s call it Phase 1) I used to regard Maltese as a homogeneous group of people whom I often generalised as ‘too loud’, ‘indifferent to art’, ‘disrespectful to nature’ or ‘enamored with fast food’. I seriously considered leaving and would have left, had the memories of the past unhappiness back in the home town been not so vivid.

In the few following years, I was lucky to meet people who made me feel at home and challenged my perceptions of Malta. In those years (Phase 2), I also met the locals whose lifestyle entirely discredited all of the clichés—some were into art and anything but loud, some worshiped nature and others loathed pastizzi. However, to my great surprise, the majority of my new ‘non-conventional’ friends were eager to convince me that, apart from them, the majority of Maltese indeed live up to stereotypes. These locals often felt foreign in Malta and sought comfort in communications with foreigners like me.

After a few years of socialising with different groups of Maltese, I began to understand the full range of diversity of Maltese society (Phase 3). I understood that Maltese were divided into a few social bubbles whose membership was defined by the family background, ties to a political party, attendance of a particular school and belonging to a particular subculture. Clearly, Maltese did not see each other as equals. I also learned that foreigners like me could enjoy an access to the upper-middle class artsy circles quicker than could ordinary Maltese (if they wished to).

Socialising with different groups of Maltese—environmentalists, festa enthusiasts, adventurers, intellectuals, hipsters, to name a few—was a process of self-discovery which taught me about my priorities more than any other past experience.

Despite the common interests, I could no longer stick with a number of artsy, well-read, entrepreneurial, predominantly Anglophone Maltese who deemed their cultural habits superior to those ‘who care nothing for art and culture‘, and held their privileges as a logical consequence of that presumed superiority. At the same time, I began to appreciate communicating with people who shared none of my long-term passions but whose honest attitudes I found compelling.

To integrate was to recognise the diversity and the complexity of Maltese society. I could no longer utter a phrase like “all Maltese are rude” or “all Maltese are racists” because I knew it was not the case. Maltese are different—a platitude from Captain Obvious which was not at all obvious a few years ago. I thought I could define fairly well what a ‘lack of integration’ means: inability to recognize diversity of a host society.

Why Do Maltese Stereotype Themselves?

Calls for integration are usually accompanied by one-dimensional claims and stereotypes of what it means to be a true Maltese—which would themselves scream lack of integration, had they been uttered by a foreigner. In fact, if successful integration into a host society means being aware and accepting of its cultural diversity, then many locals are poorly-integrated by this definition, because they do not seem to appreciate the full broad spectrum of Maltese culture.

The absence of a shared understanding of what encompasses Maltese identity exists side-by-side with numerous attempts to stereotype it. Politicians exploit these stereotypes by pointing out that it is their—and not the opponent’s—electorate that deserve the badge of ‘true Maltese’.

Adrian Delia stated that ‘true’ Maltese must necessarily be Latin and Catholic, implying that non-Catholic Maltese are ‘false’ by this definition (not to mention that such a definition downplays Malta’s Semitic language and heritage). In the case of the Nationalist Party, true Maltese-ness can even coexist with a dislike of pastizzi (remember how slamming pastizzi as ‘common and crude‘ was followed by ‘Jien nagħżel Malta’ in just a few months time?)

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Any attempt to define a national identity through a fixed, static combination of characteristics—be it religion or cultural preferences—inevitably excludes individuals who do not identify with them.[/perfectpullquote]

To some, being Maltese means respecting ‘European liberal values’ (sorry, conservatives, now it’s your turn to be rejected authenticity). Prime Minister Joseph Muscat once associated Maltese character with “positivity, optimism, energy, goodwill, unity and equality”, but I know quite a few Maltese who are neither positive nor optimistic, yet are Maltese nevertheless.

In other words, any attempt to define a national identity through a fixed, static combination of characteristics—be it religion or cultural preferences—inevitably excludes individuals who do not identify with them, despite being born and bred in Malta. Thus, stereotyping Maltese culture is a sure way to reject its great diversity. And if foreigners are expected to recognise and respect the diversity of the Maltese culture, it is fair to suppose that the locals would lead by example.

The Local Foreigners and ‘Foreign’ Locals

Although criticising Malta is generally perceived to be a habit of foreigners, locals frequently engage in it. The very same criticism of Malta meets different responses, depending on whom it comes from—a local or a foreigner.

Whenever a non-Maltese makes a gross generalisation about Malta, more often than not, he is advised to ‘go back to his country’. However, when a Maltese—unseemly indeed—labels his country ‘backwards’, nobody advises him to return to ‘his country’ … because he is already there. If fervent criticism of many things Maltese indicates foreignness, then, by this definition, many Maltese are foreigners in their country.

Thus, the major difference between living in Malta as a local from doing so as a foreigner is the privilege of the former to share opinions about the country’s rapid transformation without any remorse or fear of backlash.

It is necessary to distinguish between different kinds of criticism. Whereas labeling Malta as ‘backwards’ and ‘mediocre’ is certainly intended to disparage the country, disapproval of the rampant development, for instance, shows a genuine concern for Malta and its residents. Undeniably, nothing signifies being part of a society more than a deliberate concern for its future.

Returning back to my initial statement—what do I mean by saying that I have become a local? I have no Maltese passport, none of my parents are Maltese (nor Latin/Catholic for that matter) and my place of birth is far away from here. However, I am a local here because I have become part of its diverse community and share a genuine concern for its future. Also, I fought for my right to live here and it was not easy.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]It is the relationships I have with the locals—Maltese and non-Maltese, uncaring and sensitive—that make me part of Malta’s social fabric.[/perfectpullquote]

It is the relationships with the locals—Maltese and non-Maltese, uncaring and sensitive—that make me part of Malta’s social fabric. I admire Malta of green fields and colourful balconies as much as I am repelled by the ever-expanding construction sites and the corporate developments. I sympathise with the Maltese who struggle to afford their rent and barely make their ends meet (just as do my relatives back in Russia) as profoundly as I decry the market-worshiping developers and tax-dogging companies.

Finally, my relationship with Malta may not be simple but it certainly is non-commercial. This complicated relationship, too, makes me a local. And my experience is not unique—there are plenty of local ‘foreigners’ who grew roots here, who share my concern for Malta’s future and who wish to be accepted by the Maltese as locals. And they certainly should be.

P.S. Identifying as a local would have proved difficult had I not adopted my husband’s surname. The new surname has completed my baptism as a local, it gave me the opportunity to participate in online discussions about Malta’s transformations without fearing discrimination.

![]()

You can learn more about the author’s experiences of integration from this episode of Good Faith Podcast by Christian Peregin.

]]>