How the emblem of debauched foreign aristocracy became the ultimate symbol of Maltese identity.

by Michael Grech

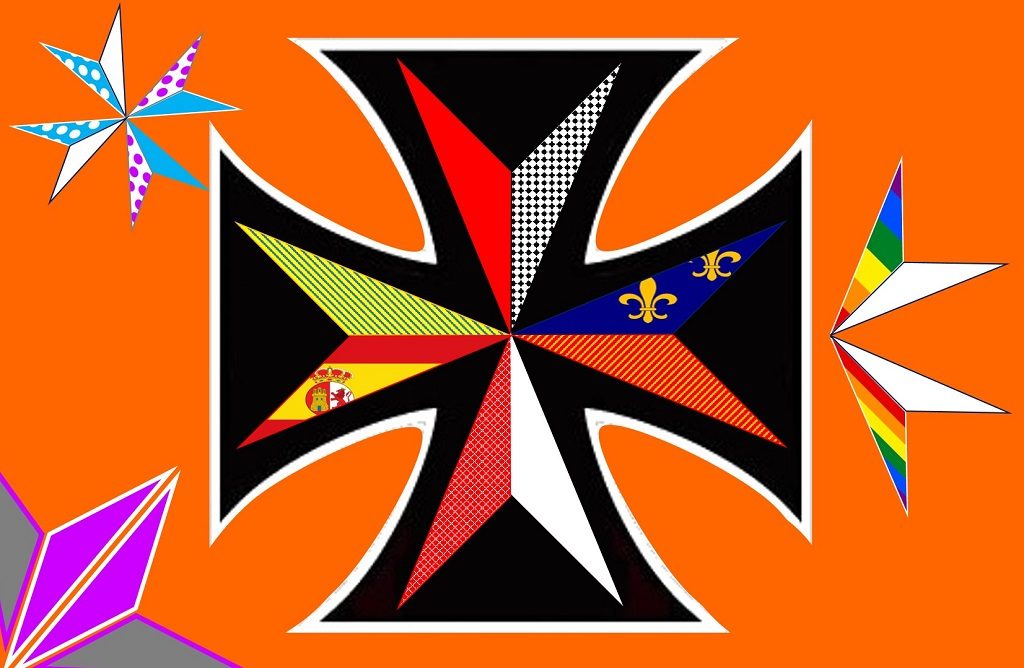

Illustration by Isles of the Left

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]any Nationalist and Conservative interpretations of the idea of the ‘national identity’ tend to consider this in monolithic and changeless terms; in terms of features and characteristics that members of the group have always had and by virtue of which they belong to the group in question. Failure to possess such features would exclude from membership in the group. The presence of ‘others’ in close geographical and social proximity, a presence which would likely encourage mixing and interaction with these others, is thought to be a threat to the group’s integrity, virtue and its very nature.

In speaking of Maltese identity, such an approach was applied by Enrico Mizzi, one of the founding fathers of local Conservative Nationalism, who monolithically conceived it in terms like ‘geography, race, history, traditions and religion’. Mizzi believed that one of the tasks of his political movement was to defend Maltese identity against the threats constituted by things like the teaching of English in school, the use of English and Maltese languages in Law Courts, and cultural and social mingling between locals and the British. The heterogeneity, the similarity to other groups, and the changes that inevitably occur to the group’s customs, are normally dismissed or regarded as secondary in contrast to some supposed common and permanent basic set features and properties.

A group’s ‘national identity’ is frequently represented by symbols. In the case of the ‘Maltese people’ one such symbol, arguably the most prominent, is the eight-pointed Maltese cross; ‘a cross made from four straight lined pointed arrowheads, meeting at their points, with the ends of the arms consisting of indented ‘v’s’’. The cross would symbolise who we are and, if national identity is characterised in the essentialist terms described above, may legitimately be used only by people who belong to our group and not by others. In recent years the cross is also being used for more sinister purposes by some right-wing groups.

Throughout the years, the cross was brought to symbolise a number of politically loaded purposes, not all of which were progressive and emancipatory.

The Maltese cross is employed in a number of ways. It is used to brand anything Maltese. It has also been used as a rallying symbol to represent national interests and/or celebrating who we feel we are. Throughout the years, the cross was brought to symbolise a number of politically loaded purposes, not all of which were progressive and emancipatory.

In the 1930s and 1960s, the cross featured prominently in a number of pamphlets and propagandistic material of the Church-conservative coalition, in their struggle first with Strickland and then with Mintoff, who were supposedly posing a threat to our islands and to their character. (Though the symbol also featured on some Stricklandian and Mintoffian material, which indicates how widespread the identification with the symbol was/is.) Today, ‘patriots’ are trying to appropriate themselves of the cross not merely to signal essential ‘Malteseness’, but also to use it as a crest in need of defence against the threat supposedly posed by foreigners, multi-culturalism, and different religious practices. In what follows I argue that the Maltese cross cannot be used to characterise a changeless, exclusive and monolithic Maltese identity since the cross and its history evidence change, evolution, heterogeneity and contagion.

Becoming What it Was Not—a Maltese Symbol

The mythological account of the Maltese cross is that it was adopted by the Order of Saint John since its inception in Jerusalem or relatively early in its life (12th century), and that it was later embraced by the Maltese when the Order came to Malta, and a bond was cemented with the islands and their inhabitants. Some believe that the cross was adopted from Amalfi (whose cross is identical to the Maltese), given that it was Amalfi merchants who founded the Order. Others hold that the eight-pointed cross represents the Beatitudes announced by Jesus, and was taken up because of the Order’s humanitarian mission of looking after the sick and destitute. Reality was different. The Order had adopted a variety of crosses before the Maltese cross as we know it was endorsed in the 16th century.

Moreover, it seems that the Maltese did not embrace the symbol during the Hospitallers’ rule. It is important to keep in mind that, in spite of the connivance and complicity between locals and Hospitallers, the Order adopted a policy of keeping the local population at an arm’s distance when it came to power and control. The Maltese could not accede to the Order. Although those formally educated amongst them could occupy various administrative roles, they were not given positions of power.

The Maltese poked fun at the cross on the Knights’ tunics by calling them ‘windmills’ (imtieћen tar-riћ), because of the similarity between the latter and the eight-pointed cross.

The Maltese tended to see the members of the Order as foreigners, whereas members of the Order frequently considered locals in Orientalist terms. What made the local population accept the Order’s presence was the real or supposed threat posed by the Ottomans. As Adrianus Koster notes, it ‘was possible for the Knights to keep Malta….[because of the] presence, imagined or real, of a mutual enemy….[and] the Turks fulfilled such a role’. That the Maltese quite probably did not adopt the symbol during the years of the Order’s presence; that they saw it as a symbol of a foreign occupying elite; is also suggested by the fact that the Maltese poked fun at the cross on the Knights’ tunics by calling them ‘windmills’ (imtieћen tar-riћ), because of the similarity between the latter and the eight-pointed cross. When locals, led by the priest Gaetano Mannarino, attempted an insurrection against the Order in the late 18th century, the cross did not feature on the flags raised by the Maltese insurgents. It seems then that it was anything but embraced by the Maltese as a symbol of their identity.

Re-inventing a Past

Most likely, the cross was gradually and widely adopted by the local population as a national symbol in the 19th century, during the British occupation of islands, when an artificial history about our past was being concocted in response to the new political and cultural situation. Politically and culturally sensitive Maltese wanted to detach themselves from their Southern and Eastern neighbours not merely religiously, but ever more culturally and ethnically. Political militants like Ugo Mifsud [1], and even progressive figures like Manwel Dimech [2], rather than opposing imperialism as such, tended to claim that the Maltese did not deserve to be treated as other British colonies because, unlike most of the latter, we were European [3]. Colonialism as such was not questioned.

The islands’ links to Europe were emphasised, exaggerated and at times invented. A greater proximity than in reality existed between the locals and the Order of Saint John was imagined. The siege of 1565 became THE EVENT. The adoption of the Order’s cross as a symbol of local identity fitted neatly into this program. The Maltese Cross was meant to allude to hagiographic and mythological pictures of past greatness; the valiant Knights of St John and their Maltese allies heroically defending ‘Christianity’ or ‘European civilisation’ from Muslims, Ottomans and non-European others. The hagiography in question and the use of the Maltese cross indicated the past greatness which Maltese wanted to emulate.

The Maltese Cross was meant to allude to hagiographic and mythological pictures of past greatness; the valiant Knights of St John and their Maltese allies heroically defending ‘Christianity’ or ‘European civilisation’ from Muslims, Ottomans and non-European others.

The belittling nature of such Eurocentric pictures—belittling and disparaging to the Maltese themselves—was as rarely questioned back then as it is hardly disputed today. The Eurocentric, hagiographic and neo-colonial view of Maltese history, celebrating some former European colonisers while culturally and politically distancing the islands from Southern European and North/East Mediterranean ‘others’, is still relatively accepted. The recent allusions by a German investor in Malta of continuing with the ‘mission’ of the Knights of St John elicited no widespread protests from the locals, many of whom seem to consider such patronising and neo-colonial attitudes acceptable.

Sinister Re-interpretations

Today, there are individuals and groups who are seeking not merely to retain the exclusive and triumphalist connotations the cross acquired, but are attempting to use it in chauvinistic and xenophobic terms against some of perceived ‘others’.

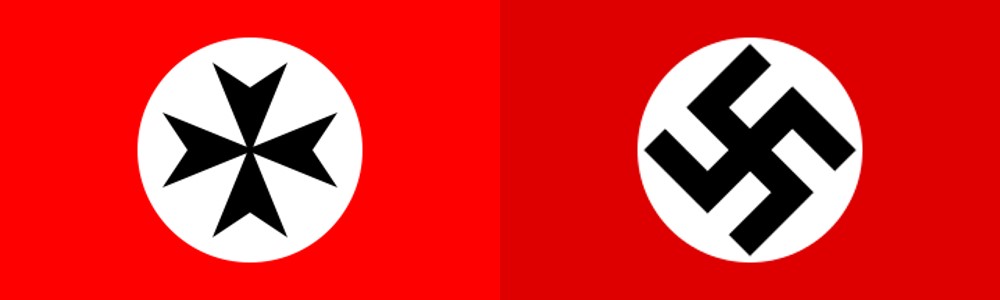

Such individuals and groups who are preoccupied with a fictional threat to our identity posed by immigrants, Muslims or foreigners in general—for instance the Extreme Right group Imperium Europa—are using the cross in place of a Swastika on a flag that is reminiscent of the one used by Nazi Party. They are also re-writing the normalised mythological history of the islands’ past in ever more jingoistic and chauvinistic terms; re-inventing a past to buttress claims of Maltese purity, virtues and greatness. The call to make Malta great again is their obvious intention.

These sinister claims rest on the perverted historical facts. Maltese cross is not an exclusively Maltese symbol. It was an emblem of debauched foreign aristocracy who was not celebrated by the Maltese during the Hospitallers rule. Moreover, no symbol—Maltese Cross or any other—can represent a ‘mythical, unchanging and monolithic’ identity because identity is essentially fluid.

![]()

[1] Joe Calleja Ugo P Mifsud Prim Ministru u Patrijott, Pubblikazzjoniet Indipendenza, 1997

[2] Michael Grech ‘X’ħasibna? Għarab Slavaġġ tal-Mokololo? – L-iskeletri fl-armarju tal-kunċett t’identita` ta’ Manwel Dimech’ f’Marco Galea Ta’ Barra minn Hawn – Ir-razza u r-Redika fil-Letteratura Maltija, Akkademja tal-Malti, 2011.

[3] Meinrad Calleja, Aspects of Racism in Malta, Daritama, 1993

The issue of Malta’s European Identity as opposed to say…African, is not an invention of the 20th century politicians. As Giovanni De Soldanis describes in detail in his magnificent 1746 manuscript “Il-Gozo…” Malta’s identity and connection with Europe was an issue of such importance in the 18th century that he begins his manuscript that chronicles Gozo on that subject. Malta’s connection to Europe was solidified many times between 1088, when Count Roger of Sicily rescued Malta from the Saracens, and the early 1700’s. Between 1551 and 1700, Gozo was attacked almost annually by Turkish fleets who were most often repulsed by European Knights residing on the islands. Thus Europe as the protector of Malta was a deep and historic, one might say ancient, connection, long before WWII ‘sealed the deal.’

Your “Fortress Europe” point of view is exactly what article seeks to challenge, in my opinion.