With a precision of scientific inquiry, the exhibition To Be [Defined] examines what it means—and feels like—to live as an antagonist in a story narrated by others.

by Francois Zammit and Raisa Galea

Picture by Alberto Favaro (adapted)

To Be [Defined] is not an ordinary art exhibition, if there is such a thing. It is not a fancy display of Instagrammable objects, neatly arranged at Spazju Kreattiv. The organisers—curator Virginia Monteforte, exhibition designer Kristina Borg, cultural advisor Alexandra Galitzine-Loumpet, project collaborator Sarah Mallia and strand coordinator Elise Billiard Pisani—defined it as ‘an artistic-anthropological exhibition dealing with past and contemporary displacement’.

Where does this description leave us?

Unlike the majority of conceptual and abstract artistic projects which tend to leave interpretations to the viewers, To Be [Defined] inscribes its message with a precision of scientific inquiry. By appealing to the aesthetic sensibilities of the viewers, the exhibition takes them on a tour de force journey through the experiences of exile which could only be interpreted in the context of grave institutional injustice.

The project does not seek to comfort the audience. The combination of hardship and beauty on display provokes outrage and begs for hope at the same time—both so vital to keep the spirit of solidarity and compassion alive in times of exclusion and apathy. The restriction of viewer’s interpretations is by no means a weakness of the project. By stating its message loud and clear, the exhibition still leaves a room for self-exploration. It poses four fundamental questions—Who are you? The one who defined? The one defined? The one to be defined?—which could lead to a surprising discovery of what it means to be who we are and who has the authority to shape our lives.

Who and What Defines Us?

Right upon stepping into the exhibition, the viewer enters a room split in half by a steel wire net. If one word could describe Do Not Cross by Alberto Favaro, it would be ‘precision’. The wire cuts through the desk in the center of the room, penetrates through the newspaper on the desk and passes through chairs. The net is light and, at first sight, does not seem to be a serious obstacle: the objects on the other side appear so within reach, albeit it is a deceiving impression. The borders, the work says, are for the people only. Bureaucracy, commodities, international sensations and data flows know no boundaries.

The Migration Objects Collective Project redefines everyday objects in the most inciting manner.

It is our memories, experiences and habits—not formal documents—that make us who we are both as a community and as an individual. Items like coffee makers, garments and other everyday paraphernalia are reimagined in a way that goes beyond their utilitarian and functional use. The ubiquitous espresso maker, found in every Italian household, is redefined as ‘a sense of home, memories, sharing’. The act of preparing coffee and the scent of the morning brew thus becomes a means of one’s memories and communal identity.

Within the same art piece there is a row of hanging clothes with a price tag attached to them. The tags, however, define a ‘human’ value and not the speculative market one. The scarf is ‘priced’ at ‘protection, warmth’—which, apart from being the practical purpose of the garment, also aptly describes the emotional dimension of the person wearing it. Just imagine the uplifting sensation that a warm woollen scarf can give to someone who is experiencing the freezing temperatures of a new land for the very first time?

In a similar poignant manner, sixteen miniature works in bronze by Katel Delia become historical artefacts; only Familja migAzzjoni–Legacy is not about a national or international history but a personal one.

In an equally touching and unsettling way these two exhibits invoke a familiar sensation we experience when looking at photos and personal items of our loved ones. In the object we recognise the person. And while observing the objects on display, we cannot escape the feeling of becoming acquainted with their owners and recognising our common humanity. Whereas the institutional discourse renders people as objects and numbers, the personal items preserve our individual identities. Living beings with memories and feelings cannot be reduced to statistics or administrative subjects, the project insists.

One of the most profound characteristics of the exhibition is that it does not draw a line between the experiences of Maltese and non-Maltese.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Maltese too were excluded from parts of Malta’s territory by the British colonial powers.[/beautifulquote]

The short autobiographical story, part of Exiled at Home by Giovanni Bonello, is a timely reminder that Maltese too were excluded from parts of Malta’s territory by the British colonial powers. As a young boy, he swam from Valletta to Manoel Island, only to be told to leave immediately by the British officers who did not empathise with the state of his utter exhaustion after crossing a stretch of sea. In 2018 this story echoes painfully. Many Maltese seem to have forgotten the meaning of solidarity and favour the idea of deportations. Manoel Island is in service to the moneyed multinationals, who once again define the rules akin to the colonial administration.

Defining Ourselves

In his poem La Malédiction (The Curse), Hassan Yassin deplores the tragedy and consequences of the dehumanising attitudes towards Africans whose presence on the Parisian streets becomes synonymous with dirt, ‘rubbish to be thrown away’. No matter how condemning and distressing, the poem gives Hassan a voice. He is no longer a passive victim, but a human being with a voice, willing to tell his own story.

Preventing us from telling our own stories is a means of stripping us from our very humanity.

By rendering a whole category of people voiceless, the state and its institutions succeed in defining them as non-human beings. They (we?) are effectively reduced to inanimate, lifeless beings who are as good as dead. The Dead are not Dead by Malik Nejmi responds to this horrific state of affairs. The video art piece is especially powerful because it gives the individual members of the Senegalese community in Firenze the opportunity to define themselves.

[beautifulquote align=”left” cite=””]Nothing About Us Without Us is both an allusion to Christian charity which should apply to all equally and a question of whether the economic growth at the price of injustice has become Malta’s new religion.[/beautifulquote]

The mass and social media have been overwhelmed and oversaturated with the images of those who brave the perilous journey towards Europe and the West but the general public is rarely exposed to their own voices, and thus the human essence of these individuals. By making their voice heard, Nejmi has led the audience to acknowledge the presence and humanity of those who are left on the kerb of Western societies.

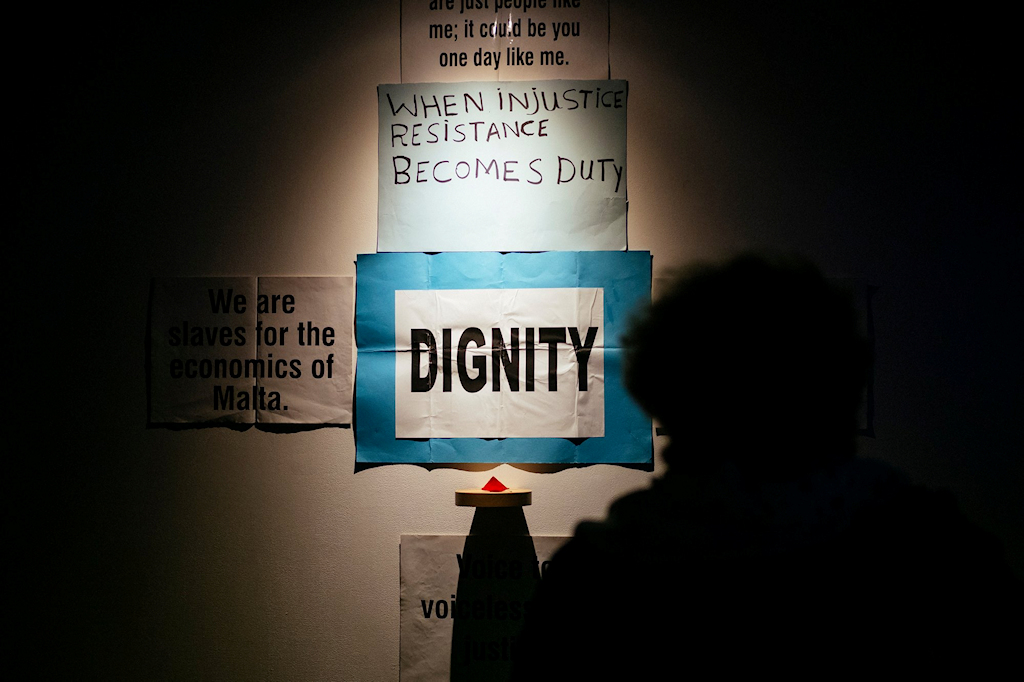

Another display, Nothing About Us Without Us, boldly confronts the audience with a rough reality that lies beneath Malta’s economic growth: the lives of poorly paid and mistreated migrant workers. In this opus the opinions of the workers resound black on white on placards which have been used during marches and protests in Malta. Together the statements form a shape of the cross: both an allusion to Christian charity which should apply to all equally and a question of whether the economic growth at the price of injustice has become Malta’s new religion.

![]()

After having been captivated, shocked, embraced and confronted by the stories on display, a viewer has no option but to question their own state of being and, more importantly, the role they play in defining and shaping the lives of others. The essence of To Be [Defined] is to examine what it means—and feels like—to live as an antagonist in a story narrated by others.

Let us too pause for a moment and ask: Who am I? What defines me? Am I the one who defines others? What responsibility do I have towards the others? Am I ‘the Other’?

To be [defined] is organised as part of RIMA project that articulates two main concepts about migration and exile: definition and construction on one side, and de-construction and resistance on the other. It features as part of the cultural programme of Valletta 2018, European Capital of Culture (Exile and Conflict strand, coordinated by Elise Billiard Pisani).

The exhibition is on display at Space C and Main Staircase, Spazju Kreattiv until Sunday, 4 November 2018. Entrance free of charge.

Leave a Reply