Outside the walls of the city ‘by and for gentlemen’ lies a boundary space where ordinary people have more say in shaping the way we share the commons. The Grand Harbour edge of Valletta outside the walls has not yet succumbed to commercial exploitation.

by Josephine Burden

Image by Raisa Galea

My view over the breakwater is both changeless and ever changing. The sea will always be there. The lights at the ends of the twin breakwaters will continue to wink red and green. The bastions built by the knights will continue to mark the boundary between sea and land. Yet every day the mood of sea and sky changes, different ships and small boats move in and out through the harbour entrance, restoration work and changing use alter the bastion walls. The view from my window has become part of my understanding of continuity. The view is a marker of identity and existence. Yet my life is shifting, settling, finding new paths.

Middle Sea Dreaming: Short Stories on a Long Journey (pending)

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he location of Valletta on a peninsula separating two harbours is a major reason why I came to live here ten years ago. The city is hemmed in by defensive walls yet opens on three sides to shore and sea. Between the walls and the sea lies an area of common ground that has been claimed by different sectors of the Valletta community for a range of uses, sanctioned or otherwise.

Walking the track outside the bastions, I have that rare sense of being ‘beyond the pale’ or outside the influence of the authorities that determine the spaces within the defensive bastions in the city “built by gentlemen for gentlemen”. Implied in that phrase, the exclusion of women and of ordinary Maltese from the Common Good of the city is brushed over as history. A few years ago, the phrase was swiftly removed from the side of the new Valletta community bus but I still hear it declared with thoughtless pride. “By gentlemen for gentlemen” denies the common good and sustains a view of Valletta as a gated community under the control of a narrow segment of the population.

Outside the walls lies a boundary space where ordinary people have more say in shaping the way we share the commons. Is sea and shore part of our common good?

Certainly, we have laws in place which require that the shore remains accessible to all. Resistance to the takeover of Manoel Island for development has secured an uneasy promise of community access, and some of our dismay in relation to the overdevelopment of St Georges Bay and Pembroke is related to our fear of losing the precious foreshore. Along with the countryside, the foreshore is central to the current struggle to retain citizen access to the commons.

![]()

Certainly also, people use the shore outside the walls to contemplate the horizon, fish and swim in the seas, walk to the ferry.

But what does it mean for the Common Good when three massive cruise liners enter Grand Harbour on the same day and pollute our air by burning heavy fuel oil to keep the air conditioning running for the passengers who are busy doubling the population of Valletta? How can we extend the Common Good of the ferry service so that other parts of Marsamxett and Grand Harbours are served? These are all aspects of this precious space outside the walls that we all need to negotiate as common good. But first let me give a sense of the place I am talking about. Here are more pieces from Middle Sea Dreaming.

I walk through the small boats and cats of the boathouse village outside the bastions of Valletta below my flat. I want to check out the new bridge to the breakwater that has been installed and is now lit up at nights in changing garish colours. A few weeks ago, I watched the new bridge lowered into place from my window. The barge arrived with the arched span from Spain where it was built in accordance with the approximate design of the old bridge that was blown up during WW2 when mini-submarines attempted to gain access to the harbour. I was elated by the precision of the operation and by the lap of honour undertaken by the Spanish ship on leaving Grand Harbour. The Maltese tugs and pilot boats tooted our thanks.

“Bongu,” I call to my neighbor who is out on the open space in front of his rooms drinking coffee. The boathouses in the village have been handed down through Valletta families for generations. At least two of my neighbours own a boathouse and spend most of their summer down there, swimming in the harbour and fishing from small boats. I envy them but know that it would be very difficult to find a way into this world of local knowledge and family inheritance.

I pause at the quay designed for the Boom Defense equipment. This defensive layer was added in WW2 by the British and involved a huge chain stretching across the harbour floor. If the harbour entrance was threatened, machinery housed in the Boom Defense rooms raised the chain to prevent access. A Valletta family now occupies the rooms and maintains the old war photos on the walls. Generations of old and young sit out on the quay in the cool of the evening. This morning I find only one man, working on his boat.

“Bongu.” I have been going to Maltese classes at the German/Maltese centre down the road from the flat. Progress is slow but some words derived from French or Italian come more easily.

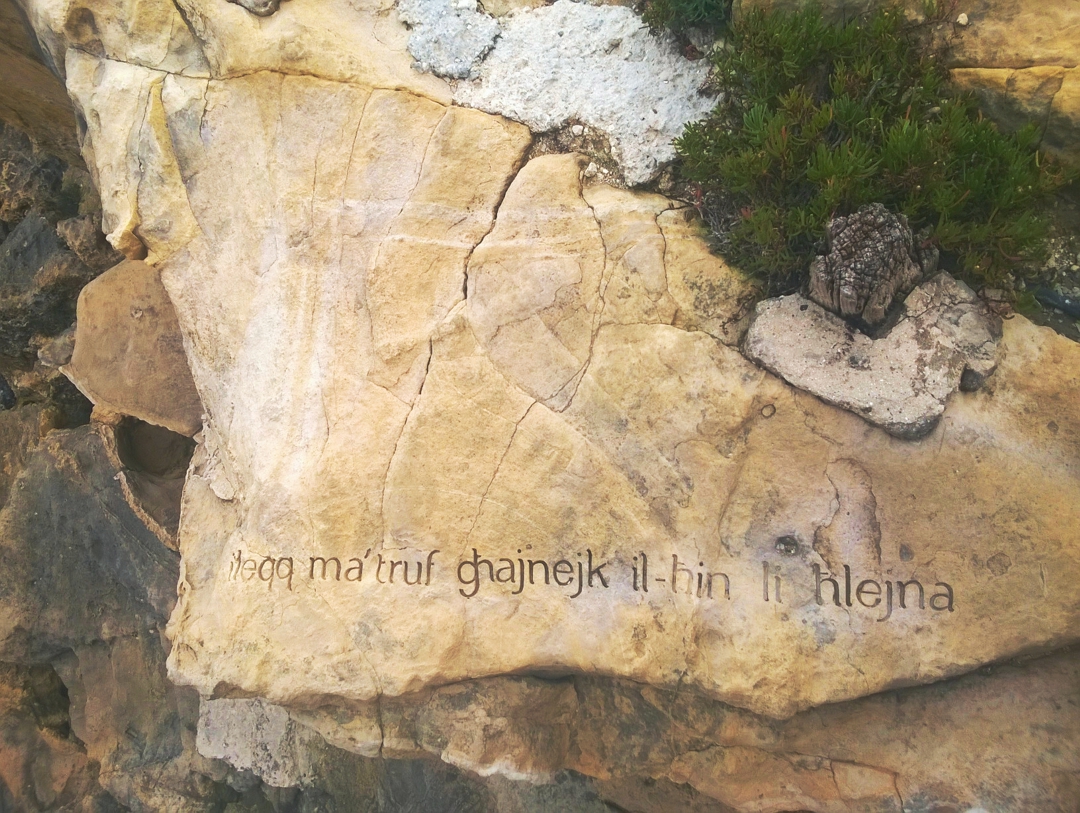

I cross the quay and climb the steps to negotiate the rocks leading to a small footbridge. I pause on the bridge to contemplate the small jetty below, carved into the rock beneath the bastions. A canyon allows access to the harbour. The cave leads to a tunnel through the walls and perhaps into the city. The morning sun casts my shadow onto the back of the cave. The sea murmurs quietly in the tunnel.

The space I am describing is informal and the rules about how we use the space have been negotiated by the people who claim it.

In summer, I go down to swim and the Valletta Local Council puts down steps off the rocks to enable our access to the water. A few adventurous tourists venture down to Lower Valletta and take a cautious dip. But the Grand Harbour edge of Valletta outside the walls has not yet succumbed to commercial exploitation even though the restoration of the Mediterranean Conference Centre resulted in a nasty gash of spilled concrete down the bastion walls.

![]()

How are things working out beyond the pale on the Marsamxett side? Come with me to walk the shoreline on that side of Valletta.

Starting from the ditch outside the landward side of the walls and now straight-edged into formal gardens, we can walk down to the ring road, added by the British and cutting around and through the bastions.

Manoel Island is due to be built up by rich people for rich people; Tigne Point sells overpriced apartments on the strength of the view of Valletta from that side of the harbor.

Here, karozzin drivers pause to point out the view of Manoel Island and perhaps mention the Lazaretto where the gentlemen Knights quarantined people with leprosy. I do not know if the drivers also mention how Manoel Island is due to be built up by rich people for rich people or how Tigne Point sells overpriced apartments on the strength of the view of Valletta from that side of the harbor. On the Valletta side, the Grand Excelsior, now the New Excelsior hotel began this takeover of the foreshore for the exclusive use of those who can afford to pay.

As we walk down the ring road, we can look down on the ruins of buildings on the rocks of the foreshore. In summer, 2018, I realized how some of these areas around Marsamxett shoreline are used by Maltese families for swimming and picnicking. Kristina Borg’s fascinating project, No Man’s Land, curated by Maren Richter as part of Dal-Baħar Madwarha, used the borderline stories of people who lived around the harbours to inform a tour of the foreshores in an electric powered luzzu. The project also spoke to the possibilities of extending the ferry service.

Further on, the buildings outside the walls are well maintained and we can walk outside the road and behind the buildings to squeeze through to the ferry stop.

The ex-Police Station built by the British has long been converted to a restaurant although recent attempts to extend the seating area met with resistance from fishers and kayakers who also use that area. The adjacent ferry is currently being upgraded. This area was originally intended as the entrance to the Mandraggio, the Knights’ proposed harbor inside the bastions.

Plans are afoot to gentrify old water polo pitch and build a lido with commercial outlets.

Past the kiosk and restaurants, past the slipway where traditional lzuz turn their defiant eyes of Horus to the bastions, we come to the old water polo pitch, now forlorn and littered with plastic. Plans are afoot to gentrify this community resource and build a lido with commercial outlets on top of the existing low building beneath the road. I am anxious that we might see a repeat of the Capo Crudo takeover of the closed Valletta Regatta Club next door where an unpermitted, permanent covering has been added along with kitchen air conditioning ducts on the roof and giant gas container adjacent to the pedestrian area.

![]()

On the opposite side of the road, the bastions are honeycombed at the base by quarried rooms with metal doors. In constructing the defensive walls, the Knights quarried down into the softer layer of rock that is exposed on the Northern edge of Malta. The dry ditch thus formed is suitable for carving out spaces on either side to serve as air raid shelters or private rooms, and for the commuter road now used by city workers to park their cars. The softly eroded rock on the seaward side, capped with a layer of harder rock, now masks the horror of the view of Tigne Point across the harbor.

Around the corner, with our backs to Tigne, we pass Jews’ Sallyport, the backdoor, tradesmen’s entrance to the city, now significant as part of the linking routes around Valletta for both pedestrians and cars. This portal also links Biċċerija, the Valletta Design Cluster, inside the walls to the foreshore area and to Maori Bar, sometimes favoured by civil action groups for their meetings. The bar next door serves the fishing community that has grown up around the small boat harbor lined by metal and timber shacks. The restoration of the bastions threatened the existence of this informal group of fishers and galvanized their collective action.

My hope lies with the sea and the ferocious power with which she batters the exposed headland and pours water into this stretch of the ditch.

Past the rock hewn baths on the left and around the corner, we are into hard rock shoreline once again and the original rough-hewn ditch of the Knights. Here the rock pools have been filled to smooth a passage for the heavy vehicles working on the replacement of the breakwater bridge. Again, I am anxious that this smoothing out may enable the extension of the road. My hope lies with the sea and the ferocious power with which she batters the exposed headland and pours water into this stretch of the ditch. Already the powerful storms have washed away the garish lights that embellished the new breakwater bridge.

![]()

You have now completed a full circuit of Valletta beyond the pale. Can we hold on to this space as a common good?

Already, the Marsamxett side of Valletta is compromised by cars and commercial outlets. Perhaps we can enlist the natural force of the sea to save the headland but we will have to be nimble and organize collectively to save Grand Harbour foreshore from cruise liners and commercial exploitation. The negotiation of the Commons is a continuous process and in future articles I will try and keep track of some of the shifts.

Read the previous chapters of the series here:

Part 1: Strada Stretta.

Part 2. Is-Suq tal-Belt.

Part 3. MUŻA.

Part 4. City Lounge and Residents’ Resistance.

Part 5. Valletta and Our Common Good: Biċċerija, Valletta Design Cluster.

Leave a Reply