A hundred years later, Sette Giugno events hit close to home. The blatant speculation and unfettered market practices that led to the spike in food prices in 1919 resemble untamed profiteering in Malta’s housing and labour markets in 2019.

text and collage by the IotL Magazine

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he year 2019 marks the 100th anniversary of Sette Giugno uprising which saw four Maltese rioters being shot to death by the British troops on June 7, 1919. In the aftermath of the First World War, food shortage and high prices of grain—abetted by merchants’ speculative ploys to push the prices further up—drove thousands of ordinary Maltese on the brink of starvation. Unable to afford bread, thousands of people gathered in Valletta and wreaked havoc on state property and private residences of profiteering importers.

How should we commemorate the events of Sette Giugno, its participants and victims one hundred years later? Should we see them as tales of the distant past? Or should we reflect on the similarities between the dire circumstances that spilled into riots back then with our contemporary realities?

At the IotL Magazine, we strongly believe that Sette Giugno events hit close to home a hundred years later. The blatant speculation and unfettered market practices that led to the spike in food prices in 1919—all in the name of profit for the few—resemble untamed profiteering in Malta’s housing and labour markets in 2019. The cost of living is steadily on the rise while wages remain low. The minimum wage of 4.4 Euro per hour guarantees little more than starvation. However, there is no revolt—not even a strike—on the horizon.

The minimum wage of 4.4 Euro per hour guarantees little more than starvation. However, there is no revolt—not even a strike—on the horizon.

Although there is a complacency of trade unions about the poor remuneration and working conditions, which also seems to be shared by many workers, we believe that hearing workers’ own stories can inspire a much-needed protest. Perhaps one day all those left behind by the booming economy will unite in strike and make their demands heard.

![]()

1. From Solidarity to Individualism: Malta’s Changing Work Culture and Organisation

by Edward L. Zammit

Recent developments in Malta’s economy and society are facilitating the emergence of a new—individualistic—work culture. Solidarity with fellow workers and high regard of trade unions are being replaced by status awareness, individualism and prioritising of promotion prospects.

Will there be a possible basis for organising widely different sectors of Malta’s current workforce? Gentrified and gentrifying workers in the service sector and the builders of their potential new homes, the construction workers with a migrant background?—A new working class consciousness would have to evolve with a strong awareness of the functioning of the economic system and a culture of solidarity. Read more here.

![]()

2. I am not Against Migration—I am in Favour of a Fair Playing Field!

a story by Emmanuel Psaila, written down by Raisa Galea

“Mid-1970s was the time when the Labour Party was in government again after a long time in the opposition. It was a revolution! The wages started to grow, especially the wages of the workers—such a great difference from how things used to be before, when clerks, or “workers of the pen” as they were called, were paid more than trade workers. My wage increased to 7 Maltese pounds per week. It was the time when the Labour party had three persons from the Drydocks as Members of Parliament—it literally was a Labour Party!” Read more here.

![]()

3. The True Cause of Low Wages in Malta? Hint: It’s Not Foreign Workers.

by Raisa Galea

Centuries of capitalism should have taught us that private employers prioritise profit above workers’ wellbeing. It goes without saying that no employer would raise wages unless they are pressed to. Moreover, employers continuously undermine workers’ solidarity by promoting a select few, thus encouraging competition between them.

The way to secure a better pay is at hand, however. When service workers—Maltese and foreign—are unionised, the General Workers’ Union could oblige the employer to pay higher salaries. It could resort to the tried and tested means of collective bargaining, such as calling for a strike. Undoubtedly, the striking service workers would make a much greater impact on hoteliers’ and restaurateurs’ decision than a polite campaign for a higher minimum wage that the union is running on social media.

Trade unions could oblige the employer to pay higher salaries. It could resort to the tried and tested means of collective bargaining, such as calling for a strike.

Clearly, workers—Maltese and foreign—are sacrificing their wellbeing and quality of life on the altar of Malta’s economic miracle. Higher wages, the business lobby cautions, would necessarily hammer the economic growth and drive the country into disarray. The role of trade unions, however, is to defend workers’ rights and wellbeing—and not growth which preys on their efforts. Read more here.

4. How Restaurant’s Owners Profit from Foreign Student’s Labour

a story by Giulia (name changed), written down by Raisa Galea

Maltese and foreign workers face similar challenges, and, in many cases, foreign workers have fewer opportunities to defend their rights.

“The employers, therefore, are spoiled for choice: they know that many foreigners, especially students like myself, are in search for a job. What interest do they have in increasing my wage, if they can employ another person with the same wage right after I leave?

I could not accept such treatment because it made me feel undeserving and a lesser human being. Although I find my current job at an eco-friendly start-up interesting, the pay still remains quite low. It barely covers food and rent expenses. We do not receive a bonus which is supposed to be paid every three months. We get no paid holidays, no vacation and no sick leave. These uncertainties wear me down.” Read more here.

![]()

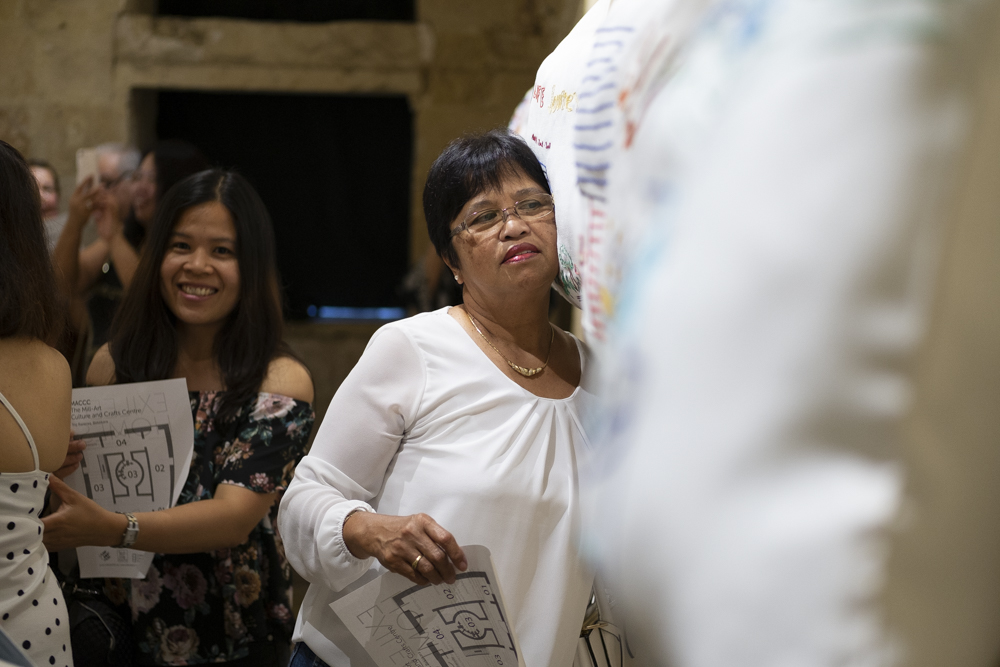

5. Exiled Homes: The Stories of Filipino Caregivers in Malta

by Raisa Galea

Whereas the presence of predominantly male migrant workers in Malta is conspicuous due to their occupation at construction sites, street maintenance and other outdoor services, Filipinas are rendered invisible by the confines of domestic sphere where they are employed. Their experiences, therefore, remain unknown and their input into the Maltese society goes unacknowledged.

Domestic labour, poorly rewarded and largely underappreciated by society, still remains the lot of women—of those who are bound to perform it in the absence of other opportunities.

The caregivers work 6 days per week, mostly 24 hours per day with 1 day off, and have 1 month leave per year, which is usually used to return to the Philippines. Although their labour is physically and emotionally demanding, it is not sufficiently rewarded in monetary terms: they are entitled to the minimum wage (€735.63 per month at the time of the interviews). Read more here.

![]()

Workers, unite, stand up for your rights and strike! You have the power to transform this society—to make it more just for everyone.

Leave a Reply